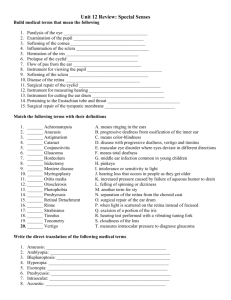

General Information & Practitioner Guidelines for Otitis Media

advertisement

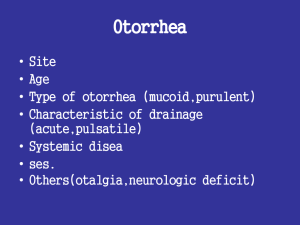

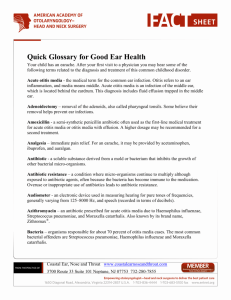

General Information & Practitioner Guidelines for Otitis Media Otitis media, the most frequently diagnosed condition in office practice for children under the age of 15, results in approximately 30 million physician visits annually. Two-third of all children in the U.S. have at least one episode of otitis media by their third birthday; up to one-half have had three or more episodes. More than 80% of children with acute otitis media will get better without the use of antibiotics as the Eustachian tube opens up and the middle ear clears itself of infection. Because many studies show that the treatment of otitis media with antibiotics increases the likelihood that a child will harbor resistant bacteria, some healthcare providers in this country have begun to follow the example of their European colleagues and are advising to wait 2448 hours to see if the infection gets better on its own before prescribing antibiotics. It is, however, important to recognize the signs and symptoms of otitis media to get a proper diagnosis and appropriate medical attention. What is otitis media? Otitis media is an inflammation of the middle ear (1)- The middle ear is a small cavity separated from the ear canal by the paper-thin eardrum. Attached to the eardrum are three tiny ear bones that vibrate when sound waves strike the eardrum, initiating nerve impulses to the brain. Air enters the middle ear through the Eustachian tube, a narrow tube that passes from the back of the throat into the ear, permitting ventilation and equalization of pressure in the middle ear so that all structures can vibrate freely. Infection is caused when bacteria and/or viruses enter the Eustachian tube from the nose or throat and become trapped in the middle ear, producing inflammation, collection of pus, and pressure. This results in pain and, since it keeps the eardrum from vibrating freely, diminished hearing. Infection usually occurs when the Eustachian tube is not functioning properly, often as a result of inflammation and swelling caused by a cold or allergy attack. (1) Bacteria are responsible for about 90-95% of cases of otitis media. The most common bacterial offenders are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. What are the types of otitis media? (2,3) Otitis media is an inflammation of the middle ear. There are several types of otitis media: Otitis media without effusion is an inflammation of the eardrum without fluid in the middle ear. Acute otitis media occurs when there is fluid in the middle ear accompanied by the rapid onset of signs and symptoms of middle ear infection. Otitis media with effusion is the presence of fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of ear infection. It is also sometimes called serous otitis media. Chronic otitis media occurs when infection persists. This can cause ongoing damage to the middle ear and eardrum. What are the symptoms of acute otitis media? (2-5) The most prominent symptom of acute otitis media is earache, often found together with the following signs and symptoms: runny or stuffy nose cough fever drainage of pus from the ear temporary hearing loss dizziness fussiness, irritability and difficulty sleeping in infants and younger children Who is at risk for acute otitis media? Otitis media occurs most commonly in the winter and early spring months. It is most common in infants and toddlers from 6 to 18 months of age, although it also affects older children and, occasionally, adults. The more horizontal angle of the Eustachian tube in infants (10 degrees) as compared to adults (45 degrees) hinders drainage. Additionally, the Eustachian tube in infants and children is shorter than in adults, allowing bacteria and viruses to find their way more easily into the middle ear and to become trapped. These two factors predispose to acute otitis media and explain the frequency of this condition in young children. Additional factors that increase the risk for acute otitis media include: Multiple upper respiratory infections. For this reason, exposure to large groups of children (e.g., daycare centers) results in more frequent colds and therefore more frequent ear infections. (3) Certain medical conditions. These include cleft palate, Down's Syndrome, allergies. Research has shown that males are more often affected than females and that whites and Native Americans/Eskimos are at higher risk than African-Americans, Asians and other ethnic groups. (3) Children under age of five who had their first ear infection before six months of age have an increased risk for recurring ear infections. (3) Not being breast-fed. Infants and toddlers who are bottle-fed are more likely to develop ear infections in early childhood. Smoking in the household. Exposure to cigarette smoke and passive smoking has been shown to have a direct relationship to the likelihood of children developing ear infections. Hereditary factors. A history of recurrent ear infections in a parent or sibling indicates a high likelihood of similar problems in other children in the family. How do you diagnose acute otitis media? A physician can diagnose acute otitis media by careful examination of the ear with an otoscope, looking for redness and fluid or pus behind the eardrum and seeing how well the eardrum moves in response to air pressure. (1) Physicians have several tests they can perform to help them determine the severity of the problem and decide on a course of treatment: An audiogram determines hearing acuity by sounding tones at various pitch levels. Hearing is usually diminished in infected ears. Acoustic reflectometry determines the presence of fluid in the middle ear by measuring how sound waves are reflected off the eardrum. Tympanometry also utilizes sound waves to measure eardrum position and stiffness as well as the presence of fluid in the middle ear. How do you treat acute otitis media? (3-4,7-8) A physician should be as certain as possible of the diagnosis of acute otitis media before prescribing an antibiotic. Since up to 85% of definite ear infections diagnosed by experienced observers get better without an antibiotic, those with an uncertain diagnosis are virtually assured of improving on their own. A physician may prescribe an antibiotic to treat otitis media. Antibiotics should be taken exactly as directed and continued until the prescription is completed, even if symptoms disappear. This allows all the bacteria to be killed. Most children with bacterial otitis media will be successfully treated with first-line antibiotics. If, however, after two days of treatment the child still has pain, fever, and a red, bulging eardrum, the bacteria causing the infection may be resistant to the first-line agent and a second-line antibiotic should be considered. Antihistamine-decongestants are useful in reducing nasal congestion and cough and promoting sleep, particularly among children with underlying allergies, but offer little or no benefit in helping to cure ear infections. Ear drops to numb the eardrum or pain-relievers taken by mouth should be used if the infection is causing discomfort. A warm washcloth on the ear can also provide comfort. Children with fever feel better if their temperature is lowered. Most of the commonly used pain-relievers (acetaminophen, ibuprofen) also act to diminish fever. Once an acute infection is over, most children will still have some fluid inside their middle ear for up to two weeks. In general, about 40% of infants and toddlers will have fluid present at 4 weeks, 20% at 8 weeks and up to 10% at 12 weeks. Although this fluid may cause some lingering hearing loss and occasional feelings of pressure or fullness in the ear (with pulling on the ear in infants), it almost always clears up on its own. How do you prevent otitis media? (3-4) Reduce the risk of catching colds by limiting exposure to large crowds. Children attending large day-care centers (10 or more children) who have frequent recurrences of acute otitis media (i.e., more than three episodes in 6 months or four in one year) might benefit from a move to a center of five or fewer. Avoidance of second-hand tobacco smoke or wood smoke is critical. Breast-feeding should be encouraged, especially among infants born into an "otitis-prone" family where either parent or one or more sibling(s) have a history of recurrent ear infections. If an infant is bottle-fed, s/he should be held in the arms during feeding. Propping the bottle or permitting a child to drink while lying on his/her back increases the risk for acute otitis media. Annual immunization with influenza vaccine for children over 6 months of age has been shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of ear infections by almost one-third. The new infant pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, which should become available for use later this year or early next year, will also be very helpful in reducing the likelihood of ear infections among young infants. Infants and children with very frequent or chronic ear infections may benefit from the placement of tympanostomy tubes in the eardrum. The benefit of adenoidectomy in reducing the incidence of recurrent ear infections is controversial, but in some cases, may be highly effective. Tonsillectomy offers little or no benefit References 1. American Academy of Otolaryngology. Head and Neck Surgery public service 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. brochure. American Academy of Pediatrics. 1998. Managing otitis media with effusion in young children. November, 94: 5. American Medical Association website. <www.AMA.org> Centers for Disease Control website. <www.CDC.gov> Journal of Family Practice. 1999. Treatment of recurrent otitis media after a previous treatment failure. Which antibiotics work best? January 48: 43-46. Nelson JD. 1987. Acute otitis media: a change in cause and therapy. APUA Newsletter 5(1): 1, 7. Levy SB. 1998. Multidrug resistance--A sign of the times. New England Journal of Medicine 338(19): 1376-1378. Levy SB. 1998. The challenge of antibiotic resistance. Scientific American 278(3):3239. Offit PA, Fass-Offit B, Bell LM. 1999. Breaking the Antibiotic Habit: A Parent's Guide to Coughs, Colds, Ear Infections and Sore Throats. John Wiley & Sons.