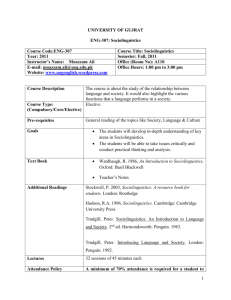

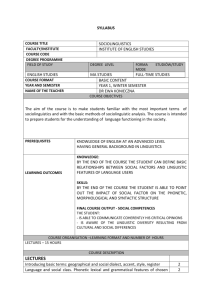

Sociolinguistics Lecture 5

advertisement

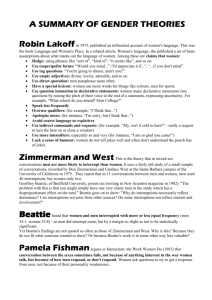

Instructor: Moazzam Ali Sociolinguistics Lecture 5 Folk Linguistics and Gender ‘Three women together make a theatrical performance’ (China). ‘Women are nine times more talkative than men’ (Hebrew). ‘Three women make a market’ (Sudan). ‘Men talk like books, women lose themselves in details’ (China). ‘Never listen to a woman’s words’ (China). ‘The tongue is babbling, but the head knows nothing about it’ (Russia). ‘Three inches of a woman’s tongue can slay a man six feet tall’ (Japan) Reflection Task Think of and note down your own examples (in any language) of the following which focus explicitly on the way women and men do and should talk: proverbs works of fiction, films, plays or songs religious texts Are you familiar with a language with sex-exclusive features? If so, what are these? Is this phenomenon undergoing change, in your experience? What happens if men do produce ‘women’s features’, and vice versa? Are children, and adult learners, taught to use these features ‘appropriately’? If so, how? Early Studies in Language and Gender Early studies about gender differences were to some extent biased (Romaine, Language in Society 103-104). These researches tried to prove that women are genetically and biologically inferior. About the inherent superiority of a boy over a girl, John Stuart Mill (1869) writes: What it is to be a boy, to grow in the belief that without any merit or exertion of his own, by the mere fact of being born a male he is by right the superior of all of an entire half of the human race (John Stuart Mill, as qtd. in Romaine, Language in Society 104). Feminist theorists put a great effort to fight against the traditional gender ideologies. As early in seventeenth century, Rochefort, one of the first Europeans who arrived in the Lesser Antilles and made contact with the Carib Indians who lived there, reports about the gender difference of language use in the Carib tribe. He says: The men have great many expressions peculiar to them, which the women understand but never pronounce themselves. On the other hand, women have words and phrases which the men never use or they would be laughed to scorn. Thus it happens that in their conversations it often seems as if women have another language than the men (qtd. in Jespersen 237). The topic of women’s and men’s speech has been of particular interest to sociolinguists. Issues include gender-differential tendencies in style-shifting (for example, between formal 1 Instructor: Moazzam Ali Sociolinguistics Lecture 5 and casual speech), use of prestige and stigmatised variants, linguistic conservatism, who leads language change (see below) and the positive and negative evaluation of such change. William Labov’s (1966, 1972a) and Peter Trudgill’s (1972a) empirical studies of variation in language use were particularly important and influential here. In his paper ‘Sex, covert prestige and linguistic change in the urban British English of Norwich’, Trudgill correlates ‘phonetic and phonological variables with social class, age, and stylistic context’ (1972a: 180). However, following Labov, he was also interested in biological sex as a sociolinguistic variable. Trudgill’s methodology was quantitative, based on a large-scale interview study (a random sample of sixty people). Looking at the variable (ng), for which there are two pronunciations in Norwich English (‘walking’, the prestige form, and ‘walkin’’), Trudgill found that women tended to use the prestige form more than men (women over thirty years of age also tended to use the prestige forms of the other phonetic variables he studied more than men).He also found that women (more than men) tended to over-report their pronunciation, that is, when asked about their pronunciation, said they produced more ‘prestigious’ sounds than they actually did. However, of particular interest, and a source of past controversy, is not so much these findings as his explanation. Again following Labov, this included that,‘Women in our society are more status-conscious than men, generally speaking . . . and are therefore more aware of the social significance of linguistic variables’ (1972a: 182). This has merited considerable feminist critique. Deborah Cameron in Feminism and Linguistic Theory suggests rather that, ‘the women’s assessments might . . . have reflected their awareness of sex-stereotypes and their consequent desire to fulfil “normal” expectations that women talk “better” In a classic study, Gal (1978) investigated language variation in the village of Oberwart, on the Hungarian and Austrian border. Looking at social networks, she found that young Hungarian women in Oberwart spoke German in a much greater range of situations than did young Hungarian men (and older Hungarian women), and that they married out of their original speech community more than the men (for whom Hungarian still had something to offer). Highlighting the importance of the local, and indeed of social practice, Gal’s study anticipated the later ‘community of practice’ (CofP) notion. CofP can be seen as going beyond the notion of ‘speech community’ to include non-linguistic social practices. It has been defined as: …….. an aggregate of people who come together around mutual engagement in an endeavour.Ways of doing things, ways of talking, beliefs, values, power relations – in short, practices – emerge in the course of this mutual endeavour. . . . [A] Community of Practice . . . is defined simultaneously by its membership and by the practice in which that membership engages. (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 1998: 490) Dominance and Difference Dominance Theory Robin Lakoff, in 1975, published an influential account of women's language. This was the book Language and Woman's Place. In a related article, Woman's language, she published a 2 Instructor: Moazzam Ali Sociolinguistics Lecture 5 set of basic assumptions about what marks out the language of women. Among these are claims that women: Hedge: using phrases like “sort of”, “kind of”, “it seems like”,and so on. Use (super)polite forms: “Would you mind...”,“I'd appreciate it if...”, “...if you don't mind”. Use tag questions: “You're going to dinner, aren't you?” Speak in italics: intonational emphasis equal to underlining words - so, very, quite. Use empty adjectives: divine, lovely, adorable, and so on Use hypercorrect grammar and pronunciation: English prestige grammar and clear enunciation. Use direct quotation: men paraphrase more often. Have a special lexicon: women use more words for things like colours, men for sports. Use question intonation in declarative statements: women make declarative statements into questions by raising the pitch of their voice at the end of a statement, expressing uncertainty. For example, “What school do you attend? Eton College?” Use “wh-” imperatives: (such as, “Why don't you open the door?”) Speak less frequently Overuse qualifiers: (for example, “I Think that...”) Apologise more: (for instance, “I'm sorry, but I think that...”) Use modal constructions: (such as can, would, should, ought - “Should we turn up the heat?”) Avoid coarse language or expletives Use indirect commands and requests: (for example, “My, isn't it cold in here?” - really a request to turn the heat on or close a window) Use more intensifiers: especially so and very (for instance, “I am so glad you came!”) Lack a sense of humour: women do not tell jokes well and often don't understand the punch line of jokes. A 1980 study by William O'Barr and Bowman Atkins looked at courtroom cases and witnesses' speech. Their findings challenge Lakoff's view of women's language. In researching what they describe as “powerless language”, they show that language differences are based on situation-specific authority or power and not gender. Of course, there may be social contexts where women are (for other reasons) more or less the same as those who lack power. But this is a far more limited claim than that made by Dale Spender, who identifies power with a male patriarchal order - the theory of dominance. This short extract from Susan Githens' report summarizes the findings of O'Barr and Atkins: O'Barr and Atkins studied courtroom cases for 30 months, observing a broad spectrum of witnesses. They examined the witnesses for the ten basic speech differences between men and women that Robin Lakoff proposed. O'Barr and Atkins 3 Instructor: Moazzam Ali Sociolinguistics Lecture 5 discovered that the differences that Lakoff and others supported are not necessarily the result of being a woman, but of being powerless.. Studies of language and gender often make use of two models or paradigms - that of dominance and that of difference. The first is associated with Dale Spender, Pamela Fishman, Don Zimmerman and Candace West, while the second is associated with Deborah Tannen. This is the theory that in mixed-sex conversations men are more likely to interrupt than women. It uses a fairly old study of a small sample of conversations, recorded by Don Zimmerman and Candace West at the Santa Barbara campus of the University of California in 1975. The subjects of the recording were white, middle class and under 35. Zimmerman and West produce in evidence 31 segments of conversation. They report that in 11 conversations between men and women, men used 46 interruptions, but women only two. As Geoffrey Beattie, of Sheffield University, points out (writing in New Scientist magazine in 1982): "The problem with this is that you might simply have one very voluble man in the study which has a disproportionate effect on the total." From their small (possibly unrepresentative) sample Zimmerman and West conclude that, since men interrupt more often, then they are dominating or attempting to do so. But this need not follow, as Beattie goes on to show: "Why do interruptions necessarily reflect dominance? Can interruptions not arise from other sources? Do some interruptions not reflect interest and involvement?" Fortunately for the language student, there is no need closely to follow the very sophisticated philosophical and ethical arguments that Dale Spender erects on her interpretation of language. But it is reasonable to look closely at the sources of her evidence - such as the research of Zimmerman and West. Geoffrey Beattie claims to have recorded some 10 hours of tutorial discussion and some 557 interruptions (compared with 55 recorded by Zimmerman and West). Beattie found that women and men interrupted with more or less equal frequency (men 34.1, women 33.8) - so men did interrupt more, but by a margin so slight as not to be statistically significant. Yet Beattie's findings are not quoted so often as those of Zimmerman and West. Why is this? Because they do not fit what someone wanted to show? Or because Beattie's work is in some other way less valuable? Pamela Fishman argues in Interaction: the Work Women Do (1983) that conversation between the sexes sometimes fails, not because of anything inherent in the way women talk, but because of how men respond, or don't respond. In Conversational Insecurity(1990) Fishman questions Robin Lakoff's theories. Lakoff suggests that asking questions shows women's insecurity and hesitancy in communication, whereas Fishman looks at questions as an attribute of interactions: Women ask questions because of the power of these, not because of their personality weaknesses. Fishman also claims that in mixed-sex language interactions, men speak on average for twice as long as women. Difference Theory An alternative explanation of women’s and men’s language use derives from the work of Daniel Maltz and Ruth Borker (1982). Maltz and Borker argued that women and men 4 Instructor: Moazzam Ali Sociolinguistics Lecture 5 constitute different ‘gender subcultures’. They learn the rules of ‘friendly interaction’ as children when a great deal of interaction takes place in single-sex peer groups. Certain linguistic features are used to signal membership of their own gender group, and to distinguish themselves from the contrasting group. These linguistic features come to have slightly different meanings within the two gender subcultures. Professor Tannen has summarized her book You Just Don't Understand in an article in which she represents male and female language use in a series of six contrasts. These are: Status vs. support Independence vs. intimacy Advice vs. understanding Information vs. feelings Orders vs. proposals Conflict vs. compromise In each case, the male characteristic (that is, the one that is judged to be more typically male) comes first. What are these distinctions? Different phases of feminism can be seen as the driving force behind the retrospectively named ‘(male) dominance’ and ‘(cultural) difference’ approaches to the study of gender and talk. To bring together her quotes from these two units, Cameron notes that, ‘Both dominance and difference represented particular moments in feminism: dominance was the moment of feminist outrage, of bearing witness to oppression in all aspects of women’s lives,while difference was the moment of feminist celebration, reclaiming and revaluing women’s distinctive cultural traditions’ (1995b: 39). Structuralist and Post-structural View of Gender Post-structuralism has provided a major challenge to essentialist notions of gender and has been crucial in the developing understanding of gender. With its emphasis on the constitutive nature of discourse it has thoroughly informed linguistic study – and indeed has been largely responsible for the ‘linguistic turn’ in many other disciplines. 2.1 Gender or Sex Most of the feminist researchers are of the view that sex precedes gender. Chanter in his book Gender: Key Concepts in Philosophy states: [T]hat is, biology, anatomy, physiology, nature, DNA structure, genetics, materiality, ‘the body’— or however one expresses it – comes before, logically or chronologically. Social structures, gendered roles, historically gendered expectations and preconceptions, cultural mores, prescriptions and taboos on sexual behavior, and so on. (43) 5 Instructor: Moazzam Ali Sociolinguistics Lecture 5 It is possible nevertheless (as many do) to see gender as a sort of social correlate of sex. Mathieu observes that ‘There is here an awareness that social behaviours are imposed on people on the basis of their biological sex (as one of the “group of men” or “group of women”)’ (1996: 49, Mathieu’s italics). A second possibility for gender is to conceptually dissociate the notion of gender from actual ‘sexed individuals’ completely, and rather to see it entirely as a set of articulated ideas about girls and boys, women and men, individually or collectively. Gender Exclusive/Inclusive Language •“Gender exclusive language discriminates on the basis of gender. It consists of words or phrases that focus on one gender unnecessarily, thereby excluding the other gender.” •Language that refers only to one gender when both genders might properly be addressed is considered, at the very least, inappropriate. •In contrast, "gender-inclusive”, also known as "gender-fair" and "non-sexist" refers to language in which both men and women are included, for example, humanity, chairperson, he/she or their. Gender Exclusive Language - Sample Paragraph: “If an insurance man contacts a family after the unexpected death of the husband, one of the first questions he may hear is, "Where is his insurance policy?" The insurance man knows that when a father dies, the meaning of life insurance suddenly becomes crystal clear. No one, at that time, asks what a man's return is on his investment. The bottom line is that life insurance provides cash when a man and his family really need it. I tell the husband that the amount his loved ones receive depends on him. I also tell him that if he gives proper attention to this matter now, few financial problems will ensue after his death.” Gender Exclusive Language - Sample Paragraph: “If an insurance agent contacts a family after the unexpected death of a family member, one of the first questions he or she may hear is, "Where is the life insurance policy?" The agent knows that when a client dies, the meaning of life insurance becomes crystal clear. No one, at that time, asks what a person's return is on an investment. The bottom line is that life insurance provides cash when clients and their families really need it. I tell the client that the amount his or her loved ones receive depends on him or her. I also tell the client that if he or she gives proper attention to this matter now, few financial problems will ensue after death.” Six main strategies for revising gender exclusive pronouns: A. Substitute a plural pronoun for the gender exclusive pronoun B. Delete the gender exclusive pronoun C. Substitute first or second person for third person D. Revise the sentence to change the subject 6 Instructor: Moazzam Ali Sociolinguistics Lecture 5 E. Use "he or she" sparingly F. Substitute an article for the masculine or feminine pronoun Consider, when it’s appropriate to do so, the use of substitutes when gender-specific language simply won't do. Instead of: Use: Mailman Letter Carrier, Postal Worker Salesman Sales Clerk, Sales Representative Cleaning Women Janitors, Maintenance Staff Mankind Humankind, People Manpower Personnel, Workers Mothering Nurturing To Man To Staff, To Operate Cameraman Camera Operator Audio Man Audio Technician Foreman Supervisor Chairman Chair, Moderator, Facilitator, or Director Stewardess Flight Attendant 7