What is the evidence for the use of salbutamol to treat hyperkalaemia?

advertisement

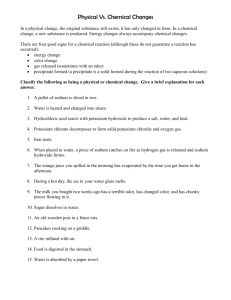

Medicines Q&As Q&A 149.2 What is the evidence for the use of salbutamol to treat hyperkalaemia? Prepared by UK Medicines Information (UKMi) pharmacists for NHS healthcare professionals Date prepared: October 2012 Background The total amount of potassium in the body is around 3000mmol; 90% of this is free and exchangeable and of this only 2% is in the extracellular fluid (ECF). Hyperkalaemia is defined as an excess concentration of potassium ions in the ECF compartment (1). It is caused by inability of the kidneys to excrete potassium (e.g. renal failure or hyperaldosteronism), impairment of the mechanisms that move potassium from the circulation into the cells, excessive intake (e.g. inappropriate use of potassium supplements), or a combination of these factors (1, 2). In addition, severe tissue damage, catabolic states, hypoxia or ketoadidosis may result in apparent hyperkalaemia due to potassium moving out and sodium moving into the cells (3). A number of medications alter potassium homeostatsis and judicious monitoring of potassium levels is important in at-risk patients receiving these medicines (2). Hyperkalaemia occurs in between 1% and 10% of hospitalised patients (1). Symptoms include weakness, fatigue, distal parasthesiae, ileus, respiratory depression and characteristic ECG changes (peaked T waves, QRS widening, diminished P waves); it may however be asymptomatic, and is potentially life-threatening. Most authorities consider that serum potassium concentrations of >6.0 mmol/L with ECG changes, or >6.5mmol/L regardless of the ECG, represents severe hyperkalaemia that warrants urgent treatment (4). Situations associated with a rapid rise in potassium (acute renal failure, rhabdomyolysis) are more strongly associated with the development of cardiac conduction disturbances. Mild hyperkalaemia is common and often well tolerated in patients with chronic renal failure (5). Urgent treatment of hyperkalaemia involves stabilising the myocardium to protect against arrhythmias (using intravenous calcium or magnesium) and reducing serum potassium levels by shifting potassium from the vascular space into the cells (using insulin and/or a beta-2 agonist). This buys more time for more definitive treatment as these measures do not remove potassium from the body. The most common treatment used to lower total body potassium is an anion exchange resin (e.g. calcium resonium); in milder cases of hyperkalaemia this may be the only intervention necessary (2). All drugs with the potential to cause potassium accumulation should be stopped in patients with hyperkalaemia – these include angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g. spironolactone, amiloride) and potassium-containing laxatives (Movicol®, Klean-Prep®, Fybogel®) (5). Answer The beta-2 agonist salbutamol causes cellular potassium uptake and is used for this property in the treatment of hyperkalaemia; it acts synergistically with insulin and they can therefore be used together (2, 6). It should be noted that none of the salbutamol products licensed in the UK are indicated for the treatment of hyperkalaemia. A Cochrane systematic review of treatments for acute hyperkalaemia was published in 2005 (1). The authors identified eight randomised controlled trials of salbutamol meeting the inclusion criteria; those involving neonates (aged <1 month) were excluded (this age group was considered in a separate review; discussed below). All trials were relatively small (range 7-70 subjects); the largest compared seven different interventions, with four involving salbutamol in addition to other medications. All appeared to be studies of convenience samples of patients with modest hyperkalaemia; the majority From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 1 Medicines Q&As had chronic renal failure and were receiving (or referred for) treatment with haemodialysis. No study reported the emergency management of life-threatening hyperkalaemia. The authors of the Cochrane analysis concluded that salbutamol is effective when given intravenously (2 studies; two doses of 4mcg/kg paediatric and 500mcg dose in adult study), in nebulised form (6 studies; 2.5-20mg), or as a multi-dose inhaler (one study; 1.2mg); appearing to provide a rapid reduction of hyperkalaemia in the setting of chronic renal failure in children and adults. One paediatric study was included (age range 5-18 years); this involved the use of two doses of nebulised salbutamol (2.5 milligrams if weight <25kg, and 5 milligrams if ≥ 25kg), and IV salbutamol (4 micrograms per kg) given on different dates. Individual study results were not amenable to metaanalysis. The overall reductions in plasma potassium when salbutamol was used as a single agent in all the studies included in the Cochrane review ranged from 0.2 mmol/L (this was seen with 10 milligram nebulised salbutamol) to 0.98 mmol/L (seen in a study utilising 20 milligram nebulised salbutamol); effects were generally seen within 30 minutes and lasted for at least two hours. A doseresponse relationship was observed in one study that compared 10 milligrams to 20 milligrams nebulised salbutamol (statistical significance reached at 120 minutes) (1). Comparison of the effects of different routes of salbutamol has only been made in one study – this found no statistically significant differences between nebulised and intravenous administration (1). The combination of salbutamol (nebulised or IV) with insulin and glucose infusion resulted in greater reductions in potassium (2 studies; reduction of up to 1.21 ± 0.19 mmol/L). No statistically significant differences were noted when IV and nebulised salbutamol were compared; for both delivery routes, a second dose at 120 minutes caused further reductions in plasma potassium concentration. No direct comparisons of salbutamol via metered dose inhaler versus nebulised or IV salbutamol were identified. Typical side-effects including tachycardia, tremors, nervousness and palpitations were reported by some participants (1). A separate Cochrane review looked at interventions for non-oligouric hyperkalaemia in pre-term (≤32 weeks) neonates, which is a distinct clinical problem (6). The authors identified only one randomised controlled trial of salbutamol meeting their inclusion criteria; although the ages (range 2-22 days) were higher than they originally stipulated (<72 hours), they included it as it was the only study evaluating the effects of salbutamol versus saline inhalation. In this study, pre-term neonates <2000g with serum potassium ≥ 6.0 mmol/L receiving mechanical ventilation were randomised to receive 400 micrograms nebulised salbutamol (n=8) or nebulised saline (n=11); treatment was given every two hours until serum potassium fell to below 5mmol/L (to maximum of 12 doses). There was no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality between the groups (RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.06-3.64). Salbutamol inhalation resulted in a statistically significant reduction in serum potassium compared to placebo, at four hours of treatment (mean difference of -0.69 mmol/L (95% CI -0.87 to -0.51) and at 8 hours (mean difference of -0.59 mmol/L; 95% CI -0.78 to -0.40). Cardiac arrhythmias did not occur in either group (7). The study was terminated before the pre-specified sample size was reached, as the use of the study drug increased outside the study protocol (8). The authors of the Cochrane review state that salbutamol inhalation, along with the combination of insulin and glucose, appear to be promising interventions and deserve further study in well designed and executed randomised controlled trials (7). A number of non-comparative studies assessing the use of salbutamol (various routes) for the treatment of hyperkalaemia in paediatric patients are available (published mainly in the 1990s); these would not have met criteria for inclusion in the Cochrane reviews and do not supply comparative data. Both the BNF and BNF for Children recommend that acute severe hyperkalaemia be treated urgently with an intravenous infusion of soluble insulin with glucose to reduce serum-potassium concentration, and calcium gluconate where indicated to manage cardiac excitability. Salbutamol (unlicensed indication) by nebulisation or slow intravenous injection may also reduce plasma-potassium concentration, but it should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular disease (9). The dosing recommendations for neonates and children are 4mcg/kg intravenous injection (single dose; repeated if necessary), or a single inhalation of 2.5-5mg nebulised solution (10). The intravenous injection is listed as the preferred route of administration, but it is noted that this has a slower onset of From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 2 Medicines Q&As action than insulin and may be less effective for reducing plasma-potassium concentration (10). Ionexchange resins may be used to remove excess potassium in mild hyperkalaemia or in moderate hyperkalaemia when there are no ECG changes (10). The CREST guidelines note that salbutamol 2.5mg/2.5mL is the standard nebuliser solution strength used, and the nebuliser chamber will hold 10mL – i.e. 10mL salbutamol. Using this will lower serum potassium by 0.5 to 1.0mmol/l by 15-30 minutes, with the effect lasting at least 2 hours. Although 20mg nebulised salbutamol may be more effective than 10mg at two hours, the lower dose is preferable in patients with ischaemic heart disease (4). The guidelines caution that salbutamol may not lower potassium in all patients, and some studies have shown that up to 40% of dialysisdependent patients are resistant to this treatment. In addition, the hypokalaemic response is attenuated in patients taking beta-blockers and digoxin. As a result, salbutamol is not recommended as a single agent to treat hyperkalaemia (4). In current practice salbutamol is not used as a first-line agent to lower serum potassium in the acute treatment of hyperkalaemia, but is a readily available second-line option if other treatments fail or are contra-indicated (11). Summary There have been a number of small randomised, controlled trials assessing the safety and efficacy of salbutamol as part of the management of hyperkalaemia. Although the studies are limited by their size, salbutamol (given intravenously, via nebulisation or via metered-dose inhaler) was found to result in reductions in plasma potassium (to varying degrees; range of 0.2 to 0.98 mmol/L between the different preparations and studies). The onset of effect was generally seen within 30 minutes and lasted for at least two hours. When used in combination with insulin/glucose, larger reductions were seen. A dose-response relationship has been observed with nebulised salbutamol, with 20mg resulting in statistically significantly higher reduction in serum potassium after two hours compared to a 10mg dose. Comparison of the effects of different routes of salbutamol has only been made in one study – this found no statistically significant differences between nebulised and intravenous administration. The trials meeting quality criteria for inclusion in a Cochrane review predominantly involved adults with chronic renal failure who were either receiving or had been referred for haemodialysis. The trials have looked at the treatment of moderate hyperkalaemia in this scenario No trials included in the Cochrane review assessed the use of salbutamol in the emergency management of life-threatening hyperkalaemia. In practice it is not used very widely for this indication, but is a readily available second or subsequent-line option if other treatments fail or are contra-indicated. The use in this situation appears to be based on practical experience rather than on evidence from clinical trials. Salbutamol may not lower potassium in all patients (up to 40% of dialysis-dependent patients are resistant to this treatment) and guidelines from CREST recommend against its use as a single agent. The hypokalaemic response is attenuated in patients taking beta-blockers and digoxin. Neonatal hyperkalaemia is a distinct clinical problem. A Cochrane review identified only one randomised controlled trial of salbutamol in this setting; this involved its use via inhalation and demonstrated a mean placebo-subtracted reduction in plasma potassium of -0.59 mmol/L No salbutamol preparation in the UK is licensed for the treatment of hyperkalaemia Limitations The studies included in the Cochrane review mainly dealt with a particular population – patients with end-stage renal failure with moderate hyperkalaemia. The Cochrane review however notes that this serves as a convenient model and should be generalisable to patients with reduced renal function, whether acute or chronic, and that there is no reason why treatments that are effective in this group would not be applicable to the general population (1). Disclaimer Medicines Q&As are intended for healthcare professionals and reflect UK practice. Each Q&A relates only to the clinical scenario described. From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 3 Medicines Q&As Q&As are believed to accurately reflect the medical literature at the time of writing. The authors of Medicines Q&As are not responsible for the content of external websites and links are made available solely to indicate their potential usefulness to users of NeLM. You must use your judgement to determine the accuracy and relevance of the information they contain. This document is intended for use by NHS healthcare professionals and cannot be used for commercial or marketing purposes. See NeLM for full disclaimer. References 1) Mahoney BA, Smith WAD, Lo DS, et al. Emergency interventions for hyperkalaemia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003235/frame.html 2) Hollander-Rodriguez JC, Calvert JF. Hyperkalemia. Am Fam Physician 2006; 73:283-290 3) Walker ER, Whittlesea C, editors. Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 4th edition. London: Elsevier Limited; 2007; p68 4) Nyirenda MJ, Tang JI, Padfield PL, Seckl JR. Hyperkalaemia. BMJ 2009; 339:1019-1024 5) CREST (2006) Guidelines for the treatment of hyperkalaemia in adults. http://www.crestni.org.uk/publications/hyperkalaemia-booklet.pdf (accessed 05/10/2012) 6) Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM, Flower RJ, editors. Pharmacology, 6th edition. London: Elsevier Limited; 2007, p382-3 7) Vemgal P, Ohlsson A. Interventions for non-oliguric hyperkalaemia in preterm neonates. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 5. http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD005257/frame.html 8) Singh BS, Farouk Sadiq H, Noguchi A, et al. Efficacy of albuterol inhalation in treatment of hyperkalemia in premature neonates. J Pediatr 2002; 141:16-20 9) Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary [Internet]. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; [October 2012; cited 5/10/12]. 10) Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary for Children. [Internet]. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; [October 2012; cited 5/10/12]. 11) Personal communication. Principal Pharmacist, Acute Medicine. Guys and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust. October 2012. Quality Assurance Prepared by Nicola Pocock, Medicines Information Pharmacist, London and South-East Date Prepared December 2008 Date Updated October 2012 Checked by Yuet Wan, Medicines Information Pharmacist, London and South-East Date of check November 2012 Search strategy Embase ([Hyperkalemia/] AND [Salbutamol/]) Medline ([Hyperkalemia/] AND [Albuterol/]) DrugDex – albuterol monograph General internet search: NeLM website, BNF website, Martindale and AHFS In-house database/resources From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 4