from the February 16, 2006 edition - http://www.csmonitor.com/2006/0216/p13s02-stct.html

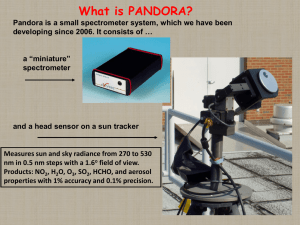

How they know what you like before you do

The high-tech tracking of people's preferences puts firms in

touch with tastes.

By Kate Moser | Contributor to The Christian Science Monitor

The other night, a few friends sat in Tracey Kennedy's Rock Island, Ill., living

room listening to music. A song by a band no one but Ms. Kennedy knew started

to play, and everyone wanted to know who it was.

Kennedy revealed that it was Silversun Pickups, an

under-the-radar Los Angeles band she'd found using an

Internet music service called Pandora.com. For her, the

website's personalized music recommendations have

sparked new listening habits. "It's like I've come back to

life," says Kennedy, a 30-something computer

programmer. "I'm getting all these vitamins I need."

Since she started listening to Pandora at work in late

October, Kennedy has bought about 35 new albums.

That's music to the ears of those who make recommendation technology. By

2010, one-quarter of online music sales will be driven by such "taste-sharing

applications," predicts a study released in December by the Berkman Center for

Internet and Society at Harvard Law School and research firm Gartner.

Over the past decade, e-commerce has taken a cue from the notion that friends

give the best recommendations. Personalized suggestions have become more

commonplace as various forms of media converge, industry professionals say,

and this could both change the entertainment industry and give consumers more

power.

What started with Amazon.com's "collaborative filtering" approach, which made

product suggestions to consumers based on what they bought, has become a

more precise science.

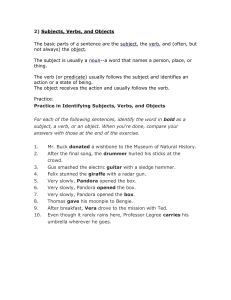

Kurt Beyer, president of Riptopia, a digital media processing company, divides

recommendation technology into two general schools: theoretical and empirical.

The theoretical approach bases its recommendations on qualities inherent in a

product. The empirical approach is similar to what Amazon.com does, gathering

large amounts of data about the buyers of a product to make recommendations

based on demographics and interests.

Recommendation technology is "exploding," claims Daren Gill, vice president of

ChoiceStream, a Cambridge, Mass., company that powers recommendations for

AOL, Yahoo Movies, and eMusic, among others.

ChoiceStream makes recommendations based on

about 25 attributes, such as "macho," "romantic,"

"mainstream," and "obscure." Eight editors monitor

the technology to make sure that when new music or

movies arrive, the automated system places them in

the appropriate category. Then algorithms create

recommendations for users based on their previous

choices.

MusicStrands, a free online music service based in Corvallis, Ore., launched last

year and is working to make "music discovery" a social activity. Last week, the

company rolled out a new version that lets users see what their friends are

listening to in real time.

"They don't want to sit down and listen to what other people are programming for

them," says Gabriel Aldamiz-echevarria, MusicStrands vice president, in a

telephone interview.

With a library of more than 5 million songs, MusicStrands provides instant

recommendations based on what someone is listening to at that moment.

Listeners can build and share playlists and "tag" music with terms such as

"contemplative" or "driving."

This kind of social interaction, the Berkman Center study predicts, will help

democratize musical tastes. "Instead of primarily disc jockeys and music videos

shaping how we view music, we have a greater opportunity to hear from each

other.... These tools allow people to play a greater role in shaping culture, which,

in turn, shapes themselves," the study states.

The Berkman study found that 58 percent of participants said they were exposed

to "a wider variety of music since using any online music service."

That kind of discovery is what Pandora is banking on. "People are so hungry to

get reconnected with music," says Pandora founder Tim Westergren. "When you

get into your 20s, music's just going to play a smaller role in your life.... You

become another person who hasn't bought an album in - you name it - number of

years."

To counteract that inertia, Mr. Westergren started the Music Genome Project. At

Pandora's offices in Oakland, Calif., about 40 musicians classify about 8,000

songs per month. They identify a song's fundamental traits from among 400

possibilities. The traits of a Beatles song, for example, might include "melodic

songwriting" and "a clear focus on recording studio production." By identifying

these attributes, Pandora connects listeners with all kinds of music - from

mainstream to obscure. At its website, people can enter a song or an artist that

they enjoy. Based on the qualities of that song or artist, Pandora then plays other

songs it thinks they'll like. If they like it, perhaps they will click on a link to an

online store and buy the music - and Pandora will get a commission.

Movie renters are expanding their horizons, too. Customers have contributed

more than 1 billion ratings on the Netflix website, says communications director

Steve Swasey, adding that 60 percent of movies rented by its 4.2 million

members are based on computer-generated recommendations. Those curious

about what films are most popular can check out the Netflix Top 100, or they can

enter their ZIP Code and find out what's hot in their neighborhood.

Community-driven Netflix recommendations are useful, says Mike Kaltschnee,

who publishes a Web log, HackingNetflix.com, which is supported partly by

Netflix and Blockbuster ads. Mr. Kaltschnee, who lives in Danbury, Conn., says

he sees friends dropping red Netflix envelopes into the mail, and conversations

about what people are watching start there, and then move online. "It's sort of

turned into a little club," he says.

But advances in recommendation technology have raised concerns about

privacy, too. Last month, iTunes customers complained about a new feature

called "MiniStore," a list of personalized recommendations based on an

individual's music library. Critics say Apple shouldn't have access to such

information.

"The more that the company tries to get into the mind of the consumer, the more

that they try to aggregate consumer information, there is the danger of blurring

those lines of what is mine and what is yours," says Mr. Beyer of Riptopia.

Will Internet companies sell profiles of their customers to others? Westergren of

Pandora says record companies have asked him many times "if any of this stuff

is for sale." It never will be, he adds.

www.csmonitor.com | Copyright © 2006 The Christian Science Monitor. All rights reserved.