Document

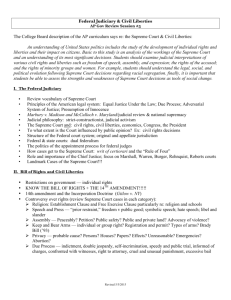

advertisement

SB Chapter 4 Civil Liberties LEARNING OBJECTIVES After students have read and studied this chapter they should be able to: Understand meaning of civil liberties. Understand how the Bill of Rights came to be imposed on state governments through the Fourteenth Amendment, and the time frame in which this happened. Identify the Constitutional basis for freedom of religion, and distinguish the establishment clause and the free exercise clause. Describe current law on the establishment of religion, especially as it pertains to the public schools (aid to church schools, prayer in schools, evolution). Describe current law on the free exercise of religion. Explain the principle of “no prior restraint. Define symbolic speech and commercial speech. Explain historical tests that have been applied to freedom of speech, especially the doctrines of “clear and present danger” and the “incitement test.” Explain the current Supreme Court definition of obscenity. Define slander and libel. Explain the development of the “right to privacy.” Give the current state of the law on abortion. Explain the current debate concerning the issue of the right to die. Identify the civil liberties pertaining to criminal rights, including limitations on police conduct, defendant’s pretrial rights and defendant’s trial rights. Explain the Miranda rule and the exclusionary rule. CHAPTER OUTLINE I. The Bill of Rights The Bill of Rights comes from the colonists’ fear of a tyrannical government. Recognizing this fear, the Federalists agreed to amend the Constitution to include a Bill of Rights after the Constitution was ratified. The Bill of Rights places limitations on the government, thus protecting citizens’ civil liberties. A. Extending the Bill of Rights to State Governments. As we have seen, federalism divides power between the national government and the state governments. While the Bill of Rights protected the people from the national government it did not protect the people from state governments. In 1868 the Fourteenth Amendment became a part of the Constitution. While this amendment did not mention the Bill of Rights it would be interpreted to impose, step-by-step, most of the Constitutional protections of civil liberties upon state governments during the twentieth century. B. Incorporation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Beginning in 1925 the United States Supreme Court began to apply specific rights stated in the Bill of Rights to state governments. Table 4-1 in the text lists the incorporation of the specific rights. However, not all of the rights have been applied to state governments at this time (e.g. the Second Amendment). II. Freedom of Religion The First Amendment addresses the issue of religion from two different venues: (1) “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,” and (2) “... or prohibiting the free exercise thereof . . .” Congress is prohibited from passing laws that establish governmental involvement in religion, and Congress is prohibited from passing laws that deny people the right to practice their religious beliefs. A. The Separation of Church and State—The Establishment Clause. 1. Aid to Church-Related Schools. In general, such aid is ruled out by the establishment clause. 2. A Change in the Court’s Position. Recently, however, in limited cases, the Supreme Court has permitted aid that goes to all schools, religious or public. 3. School Vouchers. One current controversy regarding freedom of religion and the separation of church and state is the issue of whether school vouchers can be used for religious schools. Some states’ attempts at education reform include granting student vouchers that can be used at any public or private school, including religious schools. The Supreme Court has ruled that this is permissible. 4. The Issue of School Prayer—Engel v. Vitale. The Supreme Court has ruled that officially sponsored prayer in schools violates the establishment clause. 5. The Debate over School Prayer Continues. However, the court has allowed school districts to have a moment of silence when such an event was conducted as a secular rather than religious occasion. 6. Prayer outside the Classroom. The Supreme Court has ruled that students in public schools cannot use a school’s public address system to pray at sporting events. In spite of this, students in some districts (especially in the South) deliberately violate the ruling, or use radio broadcasts to circumvent the Court’s decision. 7. Forbidding the Teaching of Evolution. The courts have interpreted the establishment clause to mean that no state can ban the teaching of evolution or require the teaching of “creationism.” 8. Religious Speech. Public schools and colleges cannot place restrictions on religious organizations that are not also placed on nonreligious ones. B. The Free Exercise Clause. The free exercise clause guarantees the free exercise of religion. Yet the Supreme Court has allowed for some restraint on free exercise when religious practices interfere with public policy. Examples of this include the ability of school districts to select texts for students, and the requirement of vaccinations for school enrollment. 1. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Passed by Congress in 1993, the act required all levels of government to “accommodate religious conduct” unless there was a compelling reason to do otherwise. In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled the act unconstitutional. 2. Free Exercise in the Public Schools. Under the No Child Left Behind act of 2002, schools can be denied federal funds if they ban Constitutionally acceptable expressions of religion. III. Freedom of Expression The First Amendment is not an absolute bar against legislation by Congress concerning speech. The First Amendment protects most speech, but some speech either falls outside the protection of the First Amendment or has only limited protection. A. No Prior Restraint. This is in effect censorship. Only on rare occasions has the government been allowed to stop the press from printing anything. If the publication violates a law, the law can be invoked only after publication. B. The Protection of Symbolic Speech. Signs, gestures and articles of clothing that convey meaning are constitutionally protected speech. Controversially, this includes the act of burning the American flag. C. The Protection of Commercial Speech. Advertisements have limited First Amendment protection. Restrictions must directly meet a substantial government interest and go no further than necessary to meet the objective. Advertisers can be liable for factual inaccuracies in ways that do not apply to noncommercial speech. D. Permitted Restrictions on Expression. 1. Clear and Present Danger. During the twentieth century, the Supreme Court has allowed laws that restrict speech that allegedly would cause harm to the public. The restrictions were principally imposed on advocates of revolution. The original test, established in 1919, was the clear and present danger test. 2. Modifications to the Clear and Present Danger Rule. In 1925, the government received great power to restrict speech through the Court’s enunciation of the bad tendency rule. In 1951, however, the Court introduced the grave and probable danger rule, which was somewhat harder for the government to meet. The current rule, established in 1969, is the incitement test. This test allows restrictions on speech only when the speech is an immediate incitement to illegal action. This test, for the first time, guaranteed free speech to advocates of revolution. E. Unprotected Speech: Obscenity 1. Definitional Problems. The current definition stems from 1973. Material is obscene if 1) the average person finds it violates community standards, 2) the work as a whole appeals to a prurient interest in sex, 30 the work shows patently offensive sexual conduct, and 4) the work lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific merit. 2. Protecting Children. The government can ban private possession of child pornography, that is, photographs of actual children engaging in sexual activity. 3. Pornography on the Internet. Congress has made many attempts to shield minors from pornography on the Internet, most of which have been found unconstitutional. However, Congress may condition federal grants to schools and libraries on the installation of “filtering software” to protect children. 4. Should “Virtual Pornography” Be Deemed a Crime? Cartoons of children engaging in sexual activity are not child pornography, since no actual children are involved in producing the images. F. Unprotected Speech: Slander. One type pf speech that falls outside the protection of the First Amendment include slander—statements that are false and are intended to defame the character of another. G. Campus Speech. 1. Student Activity Fees. Colleges may distribute such funds among student groups even when groups espouse beliefs that some students would reject. 2. Campus Speech and Behavior Codes. The courts have generally found such codes to be unconstitutional, but many continue to exist. IV. Freedom of the Press Freedom of the press is similar to freedom of speech. A. Defamation in Writing. Key concept: libel, a written defamation of character. Public figures must meet higher standards than ordinary people to win a libel suit. B. A Free Press versus a Fair Trial: Gag Orders. The courts have occasionally ruled that gag orders may be used to ensure fair trials. To this end, the courts have said that the right of a defendant to a fair trial supersedes the right of the public to “attend” the trial. C. Films, Radio, and TV. Although the press was limited to printed material when the First Amendment was proposed, the press is no longer limited to just the print media. Freedom of the press now includes other channels: films, radio, and television. Broadcast radio and TV are not afforded the same protection as the print media. Some language is not protected (filthy words) even though the language is not obscene. V. The Right to Assemble and to Petition the Government The right to assemble and to petition the government is important to those who want to communicate their ideas to others. The Supreme Court has held that state and local governments cannot bar individuals from assembling. State and local governments can require permits for such assembly so that order can be maintained. However the government cannot be selective as to who receives the permit. A. Street Gangs. Some anti-loitering laws have passed constitutional muster; others have not. Such laws cannot be vague. B. Online Assembly. Certain Web sites advocate violence against physicians who practice abortion. The limits to such “online assembly” remain an open question. VI. More Liberties Under Scrutiny: Matters of Privacy There is no explicit Constitutional right to privacy, but rather the right to privacy is an interpretation by the Supreme Court. The basis for this right comes from the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments. The right was established in 1965 in Griswold v. Connecticut. A. Privacy Rights in an Information Age. Individuals have the right to see most information that the government may hold on them. B. Privacy Rights and Abortion. A major right-to-privacy issue is abortion rights. 1. Roe v. Wade. In Roe v. Wade (1973) the court held that governments could not totally prohibit abortions because this violates a woman’s right to privacy. Government action was limited depending on the stage of the pregnancy: 1) first trimester— states may only require that a physician perform the abortion. 2) Second trimester—to protect the health of the mother, states may specify conditions under which the abortion can be performed. 3) Third trimester—states may prohibit abortions. In later rulings, the Court allowed bans on government funds being used for abortions. It also allowed laws that require pre-abortion counseling, a 24hour waiting period, and for women under 18, parental or judicial permission. 2. The Controversy Continues. The Court has approved various limits on protests outside abortion clinics. A current issue is “partial birth abortion,” or “intact dilation and extraction,” a second-trimester procedure. State governments and Congress have attempted to ban the procedure, but so far, all bans have been ruled unconstitutional. C. Privacy Rights and the Right to Die. In Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health (1997) the Supreme Court decided that a patient’s life support could be withdrawn at the request of a family member if there was “clear and convincing evidence” that the patient did not want the treatment. This has led to the popularity of “living wills.” 1. What If There Is No Living Will? For married persons, the spouse is the relative with authority in this matter. 2. Physician-Assisted Suicide. The Supreme Court has said that the Constitution does not include a right to commit suicide. This decision left states much leeway to legislate on this issue. Since that decision in 1997, only the state of Oregon has legalized physician-assisted suicide. D. Privacy Rights versus Security Issues. Privacy rights have taken on particular events since September 11, 2001. For example, legislation has been proposed that would allow for “roving” wiretaps, which would allow a person (and his or her communications) to be searched, rather than merely a place. Such rules may violate the Fourth Amendment. VII. The Great Balancing Act: The Rights of the Accused Versus the Rights of Society A. Rights of the Accused. In the United States when the government accuses an individual of committing a crime, the individual is presumed to be innocent until proven guilty. The Bill of Rights sets forth specific rights of the accused: 1. 2. 3. Fourth Amendment a. No unreasonable or unwarranted search or seizure. b. No arrest except on probable cause. Fifth Amendment a. No coerced confessions. b. No compulsory self-incrimination. c. No double jeopardy. Sixth Amendment a. Legal counsel. b. Informed of charges. c. Speedy and public jury trial. d. Impartial jury by one’s peers. 4. Eighth Amendment a. Reasonable bail. b. No cruel or unusual punishment. When the Bill of Rights was enacted, these restrictions were only applicable to the national government. The Fourteenth Amendment eventually made these rights applicable to state governments. Most of these interpretations have occurred in the last half of the twentieth century and interpretation is an ongoing process. The rights of the accused today are vastly different than the rights of the accused before 1950. B. Extending the Rights of the Accused. Today the conduct of police and prosecutors is limited by various cases, including the right to an attorney if the accused is incapable of affording one (Gideon v. Wainwright 1963). 1. Miranda v. Arizona. The Miranda ruling requires the police to inform suspects of their rights (Miranda v. Arizona 1966). 2. Exceptions to the Miranda Rule. These include a “public safety” exception, a rule that illegal confessions need not bar a conviction if other evidence is strong, and that suspects must claim their rights unequivocally. 3. Video Recording of Interrogations. In t he future, such a procedure might satisfy Fifth Amendment requirements. C. The Exclusionary Rule. This prohibits the admission of illegally seized evidence (Mapp v. Ohio 1961)