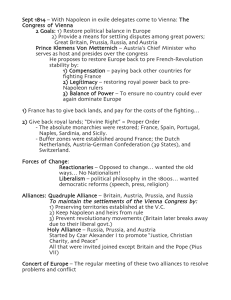

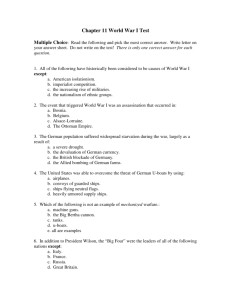

AP European history readings

advertisement