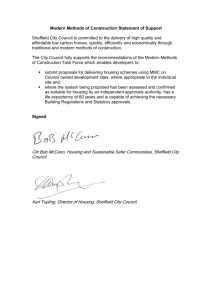

a full copy of the Sheffield Case Study

advertisement