Contents - UEF-Wiki

advertisement

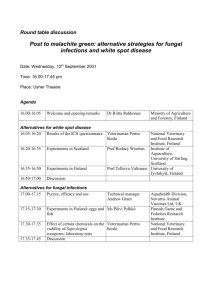

Phenomena of second homes in Finland Case of South Savo and Mäntyharju University Of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland Ronny Giambelluca, Chloe Julien, Barun Khanal, Szabina Laskai, Katerina Pavlikova, Petr Piekar, Ekaterina Bulakh, Henna Malinen, Caleb Ofosu Oppong Contents 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................................................3 2. Mobility and lifestyle migration ......................................................................................................4 2.1. Freetime and time use characteristics in Finland .............................................................. 4 2.2. Loneliness and free-time dwellings ..................................................................................... 6 Second homes and mobility..............................................................................................................8 3. 3.1. Motives for second homes mobility ..................................................................................... 8 3.2. Patterns of second home mobility ....................................................................................... 8 Impacts of second homes development ...........................................................................................9 4. 4.1. Economic impacts ............................................................................................................... 10 4.2. Social impacts ..................................................................................................................... 12 4.3. Environmental impacts ...................................................................................................... 13 4.4. Second home trends in the South Savo and Mäntyharju areas ..................................... 14 4.6 Trend of second home mobility in student´s home countries .............................................. 15 5 Second homes, legislation and rural development .............................................................. 15 5.1 Real estate legislation and second home ownership ........................................................ 16 5.2 Real Estate Legislation ....................................................................................................... 16 5.3 Environmental legislation .................................................................................................. 17 5.4 Taxes .................................................................................................................................... 18 5.5 Legislation Development .................................................................................................... 18 5.6 EU Regulations ................................................................................................................... 19 6 Conclusion............................................................................................................................... 20 1. Introduction This paper has been written as a part of NordPlus program which is held in Estonia in May 2014. NordPlus program is focusing on invisible people and also on the phenomena of second home mobility. Our international group worked with the Finnish region of South-Savo.The paper theoretically explains preconditions of second home mobility, concretely describes second home trends in South-Savo region and Mäntyharju town and also focuses on real estate legislation. Moreoevr, we have added the trends of second home mobility in student´s home countries. The definitions of second home and tourism are still controversial and have many versions in different countries. We can describe second homes as the object of the phenomenon of dwelling for recreational and secondary purposes that are owned or only utilized by the dwellers. It is not a distinct type of accommodation but includes for example cottages, vacation homes, farm houses and sometimes even caravans or boats. (MARJAVAARA, 2008, 7). Today’s second homes are not at lower level than the first home in the dwelling hierarchy (spending more time and more frequently). Dwellings are not so important like in the case of permanent homes (secondary use, recreational purposes) which results in no or low economic significance to society, so places where second homes are dominant in numbers might have some problems (it has lower value by being labelled as a “detached and non-mobile, privately owned, single family dwellings for recreational and secondary use” (Marjavaara, 2008, 8). “When work increasingly intrudes to urban people’s homes, rest and peace are sought from elsewhere, especially from the countryside. In the country people can slow down and relax away from the haste. Already thinking of the cottage relaxes me, writes a middle-aged woman. The spiritual home of my soul is located in the cottage garden, describes an elderly lady. For both of them, second home is a romantic dream come true. It is a promise of a simple life close to nature. Their second homes represent stability and are preserved from one generation to the other. For long, it was believed that once Finland becomes urbanised second homes gradually loose their importance. So far, this has not happened” (HS, 12 July 2006). Marjavaara (2008) also referred to the definition provided by ASTRID as “detached and non-mobile, privately owned, single family dwellings for recreational and secondary use”. (Astrid 2002 in Marjavaara 2008). In simple terms a second home is an accommodation that is used normally used for holiday vacations. They are normally small houses or cottages which holiday makers buy and use it during their stay. Second home are used for various reasons, many rural areas are attractive to owners of second home. Some people need them for space, land prices, proximity to leisure activities or social links to the area. The first chapter is focused on motives for second home mobility and also to patterns of second home mobility. And we also cover second home mobility in case of Finland. 2. Mobility and lifestyle migration The concept of mobility is found to be more prominent in cultural geographies of migration (Blunt, 2007) in home and family life for domestic and migrant workers. Hannam et al. (2006, pp. 9–10) describes mobility as a field that spans ”studies of corporeal movement, transportation and communications infrastructures, capitalist spatial restructuring, migration and immigration, citizenship and transnationalism, and tourism and travel”. As the trend of "the new mobilities paradigm" proposed by Sheller and Urry (2006) suggests, mobile travel allows one new mode for retirees, who are able to do full-time mobility by recreational vehicles, to actively engage in new styles of retirement life. New mobilities paradigm informs work on forms and spaces of mobility ranging from driving on roads to flying and airports. Benson and O´Reilly (2009a, pp. 609) asssociated ”lifestyle migration” as a common, growing, poorly understood phenomenon where people decide to migrate to new place with an expectation of better life than what it is in their current place. The decision for better life comes with the idea of living in better situation and searching fulfilling life after migration. This kind of movement can be for short time (eg. leisure) or long time (eg. migration), part-time (eg. old-age) of full-time, for different reasons, but for a better quality of life. Benson and O´Reilly (2009a, pp. 609) also argues that even though the phenomenon of moving for a better way of life has also been researched under study related to retirement migration, leisure migration, counterurbanisation, second home ownership, amenity-seeking and seasonal migration, these common lifestyle circumstances however can be studied under single phenomena of lifestyle migration. 2.1. Freetime and time use characteristics in Finland Generally, phenomenon of second home ownerships is very traditional in Nordic countries and we can say that this phenomenon is a part of Northern culture. Lithander et al. (2012) mention that second houses are used on average 75 days in Finland, 71 days in Sweden and 47 days in Norway per year. If we focus on the second houses in Finland, we can say, that Finnish rural second homes are most commonly wooden cottages located in the countryside in area of woods (Periäinen 2006). According to Official Statistics of Finland, by the end of 2012 there were 5.3 million dwellers in Finland and 496,200 statistically counted second homes. It is estimated that 800,000 Finns belong to cottage owner household and around three million of Fins have access to second home house through relatives and friends (OSF 2012). If we speak about location of Finnish second houses, most second houses are located outside rural community. So the landscape is characterized by spread distribution of cottages which do not for clear settlement structure. Only 14% of cottages are located in rural villages. The most part of cottages are usually spread in forests and around lakes (Vepsäläinen and Rehunen 2010). According to data available in Statistics of Finland, free time is the amount of time in a day that remains after time spent on sleep, meals, washing and dressing, gainful employment and domestic work, as well as on studying has been deducted. As we can see in the figure 1 below, percentage of time Finns spend to travel related to free time has not changed over 30 years period (1979-2009). This can be because of Finns willingness to spend time in going far from their current home. Like in most Nordic region, Finns free time use is more home-centred in winter than in summer. Another report published in 2011 explained that time use among Finns have changes through the 2000s, as the amount of free time has grown by one hour per week over the 2000s. Percentage Time Use in autumn 1979, 1987 1999 and 2009 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Free time, total Travel related to free time 1979 1987 1999 2009 Participated, % Total Travel related to free time Figure. 1: Time use survey- time used by Finns for travelling related to free-time activities (Statistics Finland, 2011) In his research with interviews with seasonal migrants’ retirees residing in Sweden and Spain, Gustafson (2001) looked into experiences of transnational mobility and multiple place attachment. Gustafson (2001) indicates that respondents regard themselves as temporary visitors in one country; adapt to local habits, enjoy cultural difference, and, to some extent, make themselves at home in Spain or in Sweden but practise “Swedish” way of life in both countries. The phenomena what Gustafson refers to as “live two different lives”. Respondents in Gustaffson’ study also informed that life in two countries to be a “highly positive experience and contribute substantially to their perceived quality of life”. This kind of migration as a motive towards sensitivity towards quality of life refers to what Benson and O´Reilly (2009a) referred to as ”lifestyle migration”. According to a report published by Statistics Finland (SF, 2011), basic characteristics of people's time use in Finland have remained quite unchanged over three decades. However, the amount of free time for Finnish people increased in Finland in 2009 as the time spent on paid employment drop off due to the economic recession, as pointed out by preliminary data concerning in the autumn of 2009 (SF, 2011). Free time and unemployment often leads to possibility to migration as a way to seek change in lifestyle. As Benson & O'reilly (2009b), referring to other past research, specified that people quest for better way of life against present negative perception of life, and as migration is way to either “getting out of trap”, “make a fresh start”, or “a new beginning” before migration. In the stories told by migrants, the book by Benson and O´Reilly (2009a) portrays narrative of migration for escape from monotonous routine life, from individualism or materialism lifestyle, life-experiences involving risk or shame, uncertaininty of economic future, isolated retirement, and thus finding migration as a way to get away from negative lifestyle towards meaningful way of life. 2.2. Loneliness and free-time dwellings Another reason for people willing to build houses in remote place can also because of Finns characteristics of fondness to be alone. A recent report published by SF indicates that Finns spend more time alone and being alone has increased over the past ten years (SF, 2009). The increase in being alone is visible for both women and men and in all age groups; however the willingness to be alone seems to be more prominent in men than with women and proportionally increases with the age. Figure 2: Indices of owner-occupied housing prices 2010-(first quarter) 2013 According to Statistics Finland, the highest numbers of new free-time residences were built in Etelä-Savo and Lapland in 2011, and the municipality with the highest number of free-time residences was Parainen. However, after the municipalities were merged in the beginning of 2013, the biggest municipalities in terms of number of free-time residences after the municipalities were Mikkeli and Kuopio ( SF, 2012). There were 496,208 free-time residences at the end of 2012. The practice of building free-time residences was a big boom in 1980s as the number of free-time residences almost doubled to 251,744 in 1980 as compared to 176,104 in 1970. Contrasted to that ratio, the latest tradition of building houses for free-time purpose seems to be only 496,208 in 2012 compared to 474,277 in 2005. However, in a report published by OSF, the numbers of free-time dwellers in past when evaluated to new free-time residents indicates that New free-time residences are on average larger than older free-time residences (SF, 2012). This indicates that even though the ratio of building free-time residents has not been increasing, on average, there are more number of new people interested in free-time dwellings. As shown in figure 2, another interesting statistics shows that even though the annual costs of owner-occupied housing rose by 0.6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013, purchases of dwellings still increased by 0.6 % during the corresponding period. (SF, 2014). Increase in the cost for maintaining housing does not decrease number of new house dwellers. 3. Second homes and mobility It is controversial that second homes are real part of tourism sector. It has not been labelled as tourists from the beginning, but second homeowners are kind of “permanent tourists”, “characterized by permanent periodic travel between the two dwellings, marked by routine” (Marjavaara, 2008, 9). They can be “new-residents” due to their residence for a long time in their second homes without being officially registered as residents. They are not seen as tourists in most of the cases. The reason is that “second home tourists are not engaged in commercial processes, owning tourism businesses, tourism associations, destination marketing authorities or appear to generate employment and hence, direct economic effects.” (Marjavaara, 2008, 9-10). This is rarely shown in official statistics on tourism. They cannot be avoided in tourism because they have important role in domestic tourism like in Finland. In general, this kind of tourism is often ignored by officials, the industry and planners, despite the fact that second home tourism has essential effects on other sectors, which are centrally viewed in development policies. In other words, impacts of second home tourism should not be neglected for the successful development. In Finland, detached houses as unoccupied dwellings by officials are often second homes. The continuous growth of cities brings environmental and health problems. Urban lifestyle is characterized by stress and speed, people want to spend time outside of the city. 3.1. Motives for second homes mobility Vepsäläinen and Pitkänen (2010) refer to Wolfe (1977) and Jaakson (1986) who point out key motives for second home holidays. These key motives are listed as key motives in Finland and also worldwide. These factors are: Connection to wild nature, counter-balance to urban life, family togetherness and the possibility to engage in various nature-based activities. Vepsäläinen and Pitkänen (2010) revealing three different aspects of rurality that the second home culture relies on: 1. The second home landscape is seen as wilderness 2. Life there imitates visions of traditional rural life 3. The environment is used for traditional consumptive and leisure activities. 3.2. Patterns of second home mobility Generally, second home tourism is a part of wider human mobility phenomena. Key concepts of human mobility are time and space (Hall 2005). Hall (2005) works with these concepts of time and space and adds the third dimension, the number of trips. “Second home tourism is strongly affected by time and space (Kauppila 2010, 164). I we are speaking about time and space, second home tourism is more intra-regional form of mobility than inter-regional. So the distance of second homes plays import role in mobility (Hall, 2005). Hiltunen and Rehunen (2014) argue that second home tourism related spatial mobility patterns and travel flows are dependent on many geographical factors and processes. They also refered to Müller (2006) and Hall and Müller (2004b) who mention that classic geographical distance decay effect influencing regional patterns of second home tourism. Hiltunen and Rehunen (2014) also refer to Pirie (2009) who mention that second homes are mainly concentrated in the hinterlands of population centres and many second homes are located close to homes of owners. But increasing human mobility, especially due to improvements in transport technology makes distance relative and relational. Different scholars point out several factors which influent second home patterns. For example Muller (2006) note that second home spatial patterns are influenced by population distribution and change, industrialization and urbanisation and also by primary economic determinants as space time accessibility, income level and real estate costs. Hiltunen and Rehunen (2014) point out that phenomenon of second home tourism and related mobility is in constant change and also influenced by the elements and processes of surrounding bio-physical and socio-cultural environments. Accordingly, cultural or spatial interaction between two places declines as the distance in between increases (Pirie, 2009). Second homes mainly concentrate in the amenity rich hinterlands of population centres and majority of second home owners live close to their second homes.” (Hiltunen and Rehunen 2014) 4. Impacts of second homes development It is important to realize to what extent and in what ways could second home influences countryside in positive or negative way. That’s why we decided to put three main spheres of impacts – economic, environmental and socio-cultural. In this chapter the development trends in the South Savo and Mäntyharju case study area will be explored against the background of areal impacts of the second home tourism. In a study of the second home tourism in Sweden, Marjavaara (2008, 12) divides the impacts of the phenomena into three main types: economic, environmental and socio-cultural impacts. First some of the impacts likely to concern the case study area will be named following this division and connected to the situation in Finland. After which the current trends and development plans applied in the area will be shortly described in order to highlight the significance of the impacts in South Savo and Mäntyharju. 4.1. Economic impacts During the restructuring of the rural economy “local population was becoming more dependent on the incomes generated by the summer guests (tourists) rather than the decreasing incomes from traditional sectors such as agriculture and fishing” (Marjavaara 2008, 12). “At the local level, second homes provide a flow of money into the importing region, through the initial purchase price of the property, spending on renovation and improvements, increased tax incomes and spending on food, leisure and other services.” (Brida, Osti, Santifaller 2011) There is possibility for local residents or second homes owners to rent their properties as another source of financial income. Second home tourism can also bring some new job opportunities. It could be also chance for small entrepreneurs or farmers who sell local products. Usually local residents cannot afford this goods, but tourists are in many cases able to give higher price for products (Marjavaara 2008). Second home development could cause negative consequences for a residents or potential residents because of increasing prices of property, local goods or services mostly in attractive areas. Also provision of additional infrastructure and services, for example garbage collection or water supply, might increase. (Brida, Osti, Santifaller 2011) Other areas of extensive economic impact are the construction, real estate and finance sectors and knowledge transfer. Second homes in Finland are typically sparsely distributed in the rural landscape. Partially due to lenient legislation the building of shores has not always been tightly regulated (Hiltunen & Rehunen 2014,6). In rural areas, permanent residents are spatially more restricted in their choice of shopping outlets. Second home tourism serves as a vital injection for the basic services, which depend on the distance between the second home and the permanent home (increasing distances reduces the local spending by the second home owners due to limited transportation capacities). Figure 3 The average distances from permanent residence municipality to second homes location according to Rehunen and Hiltunen (2014, 9). Figure 4 The travel flows of second home tourism in Finland as presented by Rehunen and Hiltunen (2014, 11). On figure 3 the average direct distances between second homes and permanent residences are shown as presented by Rehunen and Hiltunen (2014, p. 9). We can see in South Savo distances might be between 2 and 60 km, which cause less spending than further places. This is due the closeness to Helsinki. Figure 4 is about about the main direction for second home tourism from Helsinki. This represents the significance of the Lake District, especially South Savo that is the second largest region in number of second homes. South Savo was dependent on its summer visitors from all parts of Finland to keep its “lake country” viable (Rehunen and Hiltunen, p. 11). South Savo, with a large proportion of its area taken by lakes and forests had a few urban centers in the region, but these were poorly connected; connections to urban centers in Southern Finland were of more significance. Its natural beauty and branding as an “eco-province” attracted tourists and second homeowners in the summer. The number of Russian second homeowners continues to grow which results more positive economic effects (Lipkina & Hall, 2013, 164). According to Leppänen (2003 quoted in Marjavaara 2008, 14-15), “second home owners potentially create a centre of competence for rural areas, meaning that these individuals often represent firms that can be of use for firms and businesses in the local destination by sharing their knowledge and creating business opportunities.” In some municipalities in rural Finland, official meetings are held between second homeowners with their own businesses and representatives for local firms to be competitive and more innovative. 4.2. Social impacts Social impacts of second homes development are in many cases connected with conflicts of interests or opinions of locals and second home owners/ tourists. For example locals are more open to changes which could mean economic development of a locality, second home owners have an idea of preserving countryside and nature around. (Müller, 2002). Quite frequent phenomenon are clashes between locals and tourists which may occur because of different nationality, values, traditions or lifestyle. Second homeowners are often seen as representatives of urban lifestyles and urban values e.g.“alien values”, “fake or not natural culture” in contrast of permanent population e.g. on the islands of Åland the case of “shameless recreationists”. Lack of communication between those two communities could be also problematic. Second home owners, mostly from urban areas, may contribute with some know-how or useful information and can help somehow with sustaining the locality. More then a half of Finns rather not had any contact with a Russian houseowners, “51 per cent of locals and 61 per cent of cottage owners” (Lipkina & Hall, 2008). Differences in values and lifestyles cause lack of interaction e.g second homeowners strengthen the spatial segregation, which might have historical, racial and ethnic dimensions as well as distrust. Despite that most of them think that good relations with Russians are important. They represent other socio-economic status. Russians spend more and more money, which has negative effects on e.g environment (“buying more resources”) as well as more influence on decisions in development, etc. Thise has boosted misunderstandings and conflicts. One of the hottesr debates is “the demand for second homes causes a displacement of permanent residents in attractive second home destinations” (Marjavaara, 2008, p. 20). 4.3. Environmental impacts According to Breuer (2005) there are negative environmental impacts mainly in peak season because of increasing flow of people, it influences water supply, the sewage system, causes pollution. Without good planning and application of sustainable solutions it could cause significant problems. In the paper we are talking mostly about community, but it has also negative influences when people travel from their hometown to second home destination. The positive thing is, that owners of second homes are often closely connected to the nature and their house or cottage, therefore they maintain surroundings and avoid doing harm to the environment. Another positive aspect could be in reusing of abandoned houses and giving them new usage instead of being demolished or left to decay (Brida, Osti, Santifaller, 2011). High densities of second homes can potentially increase environmental degradation and competition between locals and second home owners for shared resources such as fishing and fresh water. This might cause tensions between the two groups. High utilization rate of coastal locations e.g. deteriorating water quality, erosion and decreasing public access, local flora, animals, etc. The houses being located close to the coast have impacts as well. Infrastructure, e.g. water trails, are used as a development factor in development processes, the water trail network is still not effectively utilized in the tourism development. According to Leppänen (2003 quoted in Marjavaara 2008, p. 17) in Finland, the environmental impact of second home tourism, i.e. less than 1% of all local carbon dioxide emissions, is moderate. This form of tourism has some negative impacts as ther sectors does, this is regarded as minor problem e.g. energy and resource consumption of two homes. Saimaa region is a tourist region, which consists of four administrative regions: South Karelia, South Savo, North Karelia and North Savo. In total, there are 120000 private vacation homes (2006). This is 25% of the national total (Savonlinnan Innovaatiokeskus, 2010, p. 3). Construction of new vacation homes is very active (especially in Southern areas). 4.4. Second home trends in the South Savo and Mäntyharju areas The case study area is located in Eastern Finland and comprises of two spatially overlaying administrative entities that each have legally binding duties among other interests in regional development and local governance. South Savo region consists of 14 municipalities. The regional development plan, which contains the general guidelines for the spatial distribution and extent of land reservations, is compiled by the Regional Council. The area identifies as peripheral borderlands of the European Union (Regional Council of South Savo, 2009, p. 6) and has the second most free time residences in Finland (Statistics Finland, 2013a). In the regional plan of South Savo area free time residences are recognized as vital to the wellbeing of the region (Regional Council of South Savo 2009, p. 6). It is also said that the employment patterns in Eastern Finland are concentrated around the main cities and the main road network (Regional Council of South Savo 2009, p. 6) which in South Savo case would mainly be the regional center: Mikkeli and villages. This complies with the national trends of decreasing population in the rural areas, the regional concentration of population and the dispersion of population in urban areas. On the other hand: free time residences are not typically concentrated in the Finnish tradition but built far apart from one another. According to Hiltunen and Rehunen (2014, p. 7) “The Finns typically look for solitude surroundings for rural second housing and cottages are traditionally built as far from neighbouring cottages as possible.” This is further said to have led to dispersed location patterns of second homes in Finland (Hiltunen & Rehunen 2014, p. 7). Shorelines are somewhat more concentrated areas of second home building as waterfront plots are highly sought after. This may be one of the best selling points of South Savo region as it has the largest shoreline to land area ratio in Finland (Statistics Finland, 2013b). Mäntyharju is a member municipality of the South Savo region and has close to 6300 inhabitants. Second homeowners are of particular importance to the area as there are more free time residences in the municipality than permanent residences (Statistics Finland, 2014). This is also recognized in concrete city planning and more abstract development objectives such as the vision statement of the municipality where Mäntyharju is said to “create excellent conditions for entrepreneurship, living and free time.” (Mäntyharju). The detailed plan of the Kallavesi shore area is an example of an ongoing development plan in Mäntyharju. The plan is to be approved in the beginning of 2015 after hearing the comments and notices of the affected parties on the draft version (Municipality of Mäntyharju, 2012, p. 7). So far only the general goals of the plan have been approved but the plan would seem to strengthen the existing pattern of land ownership in Mäntyharju as most of the new building area would be reserved for secondary dwellings (Municipality of Mäntyharju, 2013, p. 25). Also the development of tourism services is mentioned as a goal of the plan (Municipality of Mäntyharju, 2013, p. 26). In South Savo there are about half of the free time residences owned by people from outside of the region (Regional council of South Savo, 2014, p. 4). In 2004 about 75 % of the second homes in Mäntyharju had out-of-town owners and the amount of second home vacationers was exceptionally high in comparison to the rest of the country (Saaristoasiain neuvottelukunta 2006, p. 18). This means there is a vast population of part time inhabitants in the area that have rights to for example get involved in the regional or areal planning and utilize certain health, technical and cultural services, but do not pay the same taxes as the permanent inhabitants (Saaristoasiain neuvottelukunta, 2006, 22, pp. 41-48). The development of tourism services has been recognized in several development plans in the case study area. In the South Savo regional program for the years 2014-2017 the importance of second home tourism is evident. In general tourism is seen as an important source of employment and income. The development goal defined in the program is to make South Savo the leading region of free time residents (Regional Council of South Savo, 2014, p. 4). 4.6 Trend of second home mobility in student´s home countries The trend of second home mobility had grown in the Czech Republic during the 20th century to the position of the cultural, economic and ecological phenomenon. This phenomenon is also interesting from the sociological perspective and the Czechs are often named as a nation of second home owners. Direct or indirect experience with their use has at least half of the Czech population and second buildings account for 20% of the total of all residential buildings. This phenomenon is very usual and famous, there are movies and serials and also specific magazines about second home houses. 5 Second homes, legislation and rural development In the past, second homes were perceived as negative change in countryside, rural areas which suffered from crisis like decline in rural population, decrease farm labour, rural poverty etc. were blamed to the development of second home phenomena (Muller, 2011a). Rural areas itself go through lots of changes as technologies, modernisation, infrastructural changes as well as the impacts of globalisation. Nowadays they are considered more as a place of consumption and appreciated for its recreational and aesthetic values (Saarinen, 2004). These days conception of second homes is seen in a more positive way, predominantly because of positive economic impacts, but also negative influences still play a significant role. These negative changes are visible mainly in terms of environmental issues, therefore new approaches in second homes development are implemented, mostly dealing with sustainable way of tourism. It is hard to generalize that positive effects outbalances negative, because still depends on local circumstances which varies from place to place. 5.1 Real estate legislation and second home ownership The increase in urbanization and growth in wealth spread second-home ownership to new social classes, primarily in urban areas. The result of this development was a large number of purpose – built second homes in an attractive zone, larger cities (example: lake). There is a number of important social changes that have also meant that there has been an increase in national interest in second homes. This is where Finland, with its recurrent “cabin barometer “comes in. The barometer includes a large amount of factual information about Finnish second home (days of residence, distance work, community work, economic effect, level of equipment, infrastructure, journey and environment aspects) (Swedish Agency for Growth Policy Analysis, Rural housing. Systems and structures in Norway, Sweden and Finland). 5.2 Real Estate Legislation In Finland, direct property ownership has to do with completely owning the land and the buildings on it. The owner needs a permission from the region administration to cut down the trees on his own land (Way to Finland). There are two kinds of real estate companies in Finland: the ordinary real estate company (REC) and mutual real estate company (MREC). The ordinary real estate company (REC) is a limited liability company (it blends elements of partnership and corporate structures formed into legal partnership with the Finnish companies Act. The mutual real estate company (MREC) is a limited liability company founded under either the Finnish Housing companies or the Finnish companies Act. A foreigner can easily buy a real estate through a mortgage. The process takes around two weeks. The first thing to do is to contact local authorities and find out how the buildings on the land can be used (ProFinland). Most often you can procure about 75% mortgage on the value of the property with negotiable repayment options. Finland has chosen a method that uses state guarantees for owner-occupied housing, which is tool with very simple administration. So, whoever buys a home or builds their own house receives a state guarantee for their loan. It exist savings system for housing (BSP) which is intended to support young people ahead to purchase of their first home or secondhome. Foreigners can buy a real estate in Finland for temporary or permanent housing. To do this, he has to get permission from the local Centre of environmental protection. This permit is issued within three months after purchase or signing the contract of sale. Also, this paper can be obtained beforehand. 5.3 Environmental legislation “At national level, the Land Use and Building Act (5.2.1999/132) and the Land Use Planning Decree (10.9.1999/895) are the key instruments governing second-home development. They regulate the use of land and water areas and building activities, including second homes. On the other hand, the formal National Land Use Guidelines control spatial planning at a general level. An emphasis of these key national level documents is on building issues in general, without specifying second homes, except in a few areas concerning ecological values and the attractiveness of shore areas” (Janne Rinne, Riikka Paloniemi, Seija Tuulentie & Asta Kietäväinen, 2014, p. 5). Currently, the legislation on environmental protection and construction in Finland is strict, especially on building on the shores. However, it has been not always tightly regulated. (Findacha; Hiltunen & Rehunen 2014, p. 6) Regional councils prepare regional plans at the most general level, however, in practice, the municipal regional organisations are responsible for both regional policy planning and for land use planning. Planning at a regional level includes a regional overview, a regional plan that governs other area planning and a regional development programme. Municipal planners and elected members of municipal counsels are mainly making decisions concerning second homes. Anyone can participate in decision making if their interest are affected by land plans. Second-home owners have to give formal statements and make appeals about their plans on using the land (Janne Rinne, Riikka Paloniemi, Seija Tuulentie & Asta Kietäväinen, 2014, p. 5). 5.4 Taxes The buyer of a property in Finland is required to pay property tax on the property located in Finland. The tax on property is calculated according to percentages that are set by the municipality in which the property is located. The amount of transfer tax is four percent (4%) of the price of the property when it’s a real estate and 1.6% of the price when it is the purchase of shares. Registration of real estate ownership in Finland will require some costs (Way to Finland). The owner is obliged to pay annually the real estate tax, which currently stands at 0.50-1.0%, as well as the real estate tax, which is used as a permanent dwelling-0.22-0.50% of the cadastral value of the property (ProFinlad). Right after the acquisition of the real estate in Finland the foreigner receives the confirmation of ownership, so he just goes to the Consulate and gets a visa for a period of 1 year, where he can stay in the country up to 90 days every six months (Villa Suomi). Foreign nationals are able to buy property in all areas of Finland excluding the province of Ahvenanmaa, without any special permission (Inostrannik). 5.5 Legislation Development During the soviet Era, it was illegal to own property, all the lands were communally owned. However after the collapse of the Soviet Union it became legal to own property. This has led to the phenomena of many Russian businessmen and other ordinary nationals acquiring property including second homes in Finland. There was a glut of business activity in the end of the last century. It had had a positive impact on the real estate market. At that time, tenants and buyers were mostly interested in real estates adjacent to Helsinki and Tampere, Oulu, Jyväskylä and Turku. The Sharp increase in demand for real estate in these areas has resulted in considerably high price of rent in Finland (ProFinland). Russians are generally interested in accommodation in Imatra, Lappeenranta, Mikkeli, Kuopio, Jyväskylä, Punkaharju and Savonlinna. Russians are watching carefully towards the South of Finland. It is quite far away from Saint - Petersburg, moreover it is more expensive. In the North of the country there is a very well - developed tourism. It is a home to Santa Claus, and in winter, thousands of tourists come here from all around the world. This makes Lapland very attractive for buying real estate for the purpose of eventual lease. In the middle of Finland there are a lot of colleges and universities, and thus most of the real estate is sold cheap counted upon students. It is estimated that, as of 2012, there were an estimated 50007000 properties in Finland which are owned by Russians. 5.6 EU Regulations For professor Ole Reiter, there is a rural development processes that unite the Nordic Countries. Indeed, until the 1970’s, the emphasis in municipal planning was on the expansion of large scale housing projects and other infrastructure projects. After Finland joined the EU in 1995, it had to make a few alterations to its laws concerning European Union’s laws, by the year 2000 it had made all the necessary changes to conform to the EU regulation on property ownership. Article 56 of the Treaty establishing the European Community states that: “The free movement of capital as a fundamental freedom enshrined in the Treaties means far more than simple currency exchanges. The free movement of capital also includes the rights of citizens and businesses to purchase shares in companies established in a different Member State, or to purchase property such as a holiday home or secondary residence.. …………..It must be stressed that the free movement of capital between Member States remains fully assured.” Therefore it was necessary for Finland to adhere to this requirement and it did so by making gradual changes until the year 2000 when it completed the changes. In conclusion it can be stated that second home ownership still remains as a thriving business venture and the phenomenon is going to increase steadily in the years ahead. 6 Conclusion Finland second home tourism is today probably one of the most vital elements in the development of rural areas.( (Marjavaara 2008). One of the key points is to define what the second homes are, what the motives of people are and what influent patterns of second home mobility. The decision for better life comes with the idea and search for living in better situation and thought of fulfilling life after migration. So migrants move to new place short, long time, old-age of full-time and for different reasons for a better quality of life. Second home ownerships is a common phenomenon in Nordic countries and is even considered as a part of Northern culture. In case of Finland, people still like to be spend time alone, they value nature, and thus spend their free time out of their everyday-homes and tend to buy or as an inheritance. People also move to new place to get away from monotonous routine life, individualism lifestyle, life-experiences, and thus can also be a way to find migration as a way to get away from negative lifestyle towards meaningful way of life. And it seems like migrating to second homes being social, economic, environmental issues to the new home location. However, people are still people and they might want to live in their known surrounding and thus they bring new culture, way of living to the new place. There are several factors which influent second home mobility and there is no doubt that these motives vary worldwide. These impacts have major role in displacement discourse. Nature tourism (concluding second home tourism) in the tourism development plan of the province of South Savo (Mika Lehtolainen) aims to increase the profitability and number of tourism enterprises regional income and the level of employment, and the amount of tourists and length of visitor stay in the area (p. 1-2). Other goal is to double the jobs in the sector (Mika Lehtolainen). We suggest it is necessary to perceive every locality as a unique. It is important to analyse economic, social and environmental impacts of second home tourism with purpose to avoid or reduce problematic aspects while emphasize and develop positive aspects. With smart planning or certain programs could be second home tourism, the same as other forms of tourism, sustainable and preserved for the future generations. References ASTRID (2002). Geo-referenced database, generated by Statistics Sweden, containing all properties and individuals in Sweden: 1991-2002. Department of Social and Economic Geography. Umeå: Umeå University. Benson, M., & O'reilly, K. (2009a). Migration and the search for a better way of life: critical exploration of lifestyle migration. The Sociological Review.57:4. p. 608-624. Benson, M., & O'reilly, K. (Eds.). (2009b). Lifestyle migration: Expectations, aspirations and experiences. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. Benson, Michaela & Karen O´Reily. 2009. Migration and the search for a better way of life: critical exploration of lifestyle migration. The Sociological Review.57:4. p. 608-624. Blunt A. 2007. Cultural geographies of migration: mobility, transnationality and diaspora Progress in Human Geography. first published on September 10, 2007. doi:10.1177/0309132507078945 Brida J., Osti L., Santifaller E. (2011) Second homes and the need for policy planning Buying property http://www.expatfocus.com/expatriate-finland-buyingproperty?gclid=CKeytLz1870CFcTbcgodygwAxA accessed on 23rd April ,2014. Cresswell, T. 2010. Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and planning. D, Society and space, 28(1), 17. EU laws on property ownership http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/internal_market/single_market_capital/l2 4404_en.htm accessed on 22nd April, 2014. Gustafson, P. 2001. Retirement migration and transnational lifestyles. Ageing and Society, 21, pp 371-394 doi:10.1017/S0144686X01008327 Hall CM (2005). Time, space, tourism and social physics. Tourism Recreation Research 30: 1, 93–98. Hannam, K., Sheller, M. and Urry, J. 2006. Mobilities, immobilities and moorings. Mobilities 1, 1–22. Hiltunen & Rehunen (2014). Second home mobility in Finland: Patterns, practices and relations of leisure oriented mobile lifestyle. Fennia 192:1, 1-22. Hiltunen, M. J. (2007). Environmental Impacts of Rural Second Home Tourism. Case Lake District in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 7(3), 243-265. Hiltunen, Mervi Johanna & Antti Rehunen (2014). Second home mobility in Finland: Patterns, practices and relations of leisure oriented mobile lifestyle. Fennia 192: 1, pp. 1–22. ISSN 1798-5617. HS, 12 July 2006. Kesämökki on yhäse rakkain paikka (summer cottage is still the dearest place). Helsingin Sanomat/Marja Salmela. http://www.tillvaxtanalys.se/download/18.56ef093c139bf3ef89029cb/13498640 58424/Rapport_2012_05.pdf 01.05.2014. http://waytofinland.ru/dacha-v-finland accessed on 23rd April, 2014. Jaakson (1986). Second-home domestic tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 13, 367–391 Jobes, P. C. 1984. Old timers and new mobile lifestyles, Annals of Tourism Research, Volume 11, Issue 2, 1984, Pages 181-198, ISSN 0160-7383, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(84)90069-0. Kauppila, Pekka (2010). Resorts, second home owners and distance: a case study in northern Finland. Fennia 188: 2, pp. 163–178. Helsinki. ISSN 00150010. Lehtolainen, M. Public infrastructure investments and their rolw in tourism development in the finnish lake region. Lake Tourism Project. <https://www.uef.fi/documents/1145891/1362837/mika_iltcpaper.pdf/59cca4f7ffff-48e3-96bb-65bff11d9a51> Lipkina O. & C. M. Hall (2008) Involvement in the local community, Russian second home owners in Eastern Finland. Lipkina O. & C. M. Hall (2013) Russian second home owners in Eastern Finland: Involvement in the local community. In Janoschka, M. (ed.). Contested Spatialities of Lifestyle Migration, 159-172. Routledge, London. Lipkina, O. (2013). Motives for Russian second home ownership in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 13:4, 299-316. Lithander J, Tynelius U, Malmsten P, Råbock I & Fransson E 2012. Rural Housing – Landsbygdsboende i Norge, Sverige och Finland. Tillväxtanalys, Rapport 05. Östersund. Nordic Council of Ministers. Marjavaara, R. (2008). Second home tourism: The Root to Displacement in Sweden? (Doctoral dissertation). ISBN 978-91-975696-8-2. Retrieved from diva-portal.org. (Accessed on 7.5.2014) Marjavaara, R. (2008): Second home tourism. The Root to Displacement in Sweden? GERUM – kulturgeografi 2008:1 <http://www.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:141659/FULLTEXT01.pdf> McIntyre, N. (2006). Introduction, In McIntyre, N., Williams, D. and McHugh, K. (Eds.) Multiple Dwellings and Tourism: Negotiating Place, Home and Identity. Wallingford: CABI. Muller D., Hoogendoorn G. (2013) Second Homes: Curse or Blessing? A Review 36 Years Later Müller DK (2006). The attractiveness of second home areas in Sweden: a quantitative analysis. Current Issues in Tourism 9: 4–5, 335–350. Müller DK, Hall CM & Keen D (2004). Second home tourism impact, planning and management. In Hall CM & Müller DK (eds). Tourism, mobility and second homes. Between elite landscape and common ground, 15–32. Channel View Publications, Clevedon. Muller, D. K. (2011a). Second homes in rural areas: Reflections on a troubled history. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift, 65(3), 137–143. Müller, D.K. (2002). Second home tourism and sustainable development in north European peripheries. Tourism and Hospitality Research Surrey Quarterly Review, Vol.3 Muller,D.K.(2002a).German second home development in Sweden .In C.M.Hall & A.M.Williams (Eds.), Tourism and migration: New relationships between production and consumption (pp. 169–185). Dordrecht: Kluwer Municipality of Mäntyharju (2012). Kallaveden rantaosayleiskaava: osallistumis- ja arviointisuunnitelma.<http://www.mantyharju.fi/tiedostot/tekniset_palvelut/Kaa voitus/Kallavesi/OAS_Kallavesi_paivitetty_251113.pdf> 5.5.2014. Municipality of Mäntyharju (2013). Kallaveden rantaosayleiskaava: Perustiedot ja tavoitteet. <http://www.mantyharju.fi/tiedostot/tekniset_palvelut/Kaavoitus/Kallavesi/Peru stiedot_ja_tavoitteet_151013.pdf> 5.5.2014. Municipality of Mäntyharju. Strategiat. http://www.mantyharju.fi/hallinto/139strategiat. 4.5.2014. Official Statistics of Finland (OSF). 2009. Time use survey [e-publication]. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [accessed on: 4.5.2014]. Retrieved from: http://www.stat.fi/til/akay/2009/06/akay_2009_06_2014-0206_tie_001_en.html. Official Statistics of Finland (OSF). 2011. Buildings and free-time residences [epublication]. ISSN=1798-6796. 2011. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [accessed on: 4.5.2014]. Retrieved from: http://www.tilastokeskus.fi/til/rakke/2011/rakke_2011_2012-0525_tie_001_en.html. Official Statistics of Finland (OSF). 2011. Time use survey [e-publication]. Changes 1979 - 2009 2009. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [accessed on: 4.5.2014]. Retrieved from: http://www.stat.fi/til/akay/2009/02/akay_2009_02_2011-0217_tie_001_en.html. Official Statistics of Finland (OSF). 2012. Buildings and free-time residences [epublication]. ISSN=1798-6796. 2012. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [accessed on: 4.5.2014]. Retrieved from: http://www.tilastokeskus.fi/til/rakke/2012/rakke_2012_2013-0524_tie_001_en.html. Official Statistics of Finland (OSF). 2014. Indices of owner-occupied housing prices [e-publication]. ISSN=2341-6971. 4th Quarter 2013. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [accessed on: 4.5.2014]. Retrieved from: http://www.tilastokeskus.fi/til/oahi/2013/04/oahi_2013_04_2014-0404_tie_001_en.html. OSF (2012). Official Statistics of Finland. Dwellings and housing conditions 2011. Housing 2012. < http://www.tilastokeskus.fi/til/asas/2011/01/asas_2011_01_2012-10-24_en.pdf >. 1.5.2014. Periäinen K (2006). The summer cottage: a dream in the Finnish forest. In McIntyre N, Williams D & McHugh K (eds). Multiple dwelling and tourism: negotiating place, home and identity, 103–113. Cabi, Wallingford. Pirie GH (2009). Distance. In Kitchin R & Thrift N (eds). International encyclopedia of human geography, 242–251. Eelsevier, Amsterdam. Pitkänen, K. & M. Vepsäläinen (2008) Foreseeing the Future of Second Home Tourism. Case Finnish Media and Policy Discourse. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 8(1), 1-26. Real estate legislation and tax system http://www.amcham.fi/wpcontent/uploads/2012/04/Legal_Guide_2011.pdf assessed on 23rd April 2014. Regional Council of South Savo (2009). Etelä-Savon maakuntakaava, selostus. Etelä-Savon maakuntaliiton julkaisu 98:2009. Regional Council of South Savo (2014). Etelä-Savo ohjelma: Maakuntaohjelma vuosille 2014-2017 (draft 21.2.2014). http://www.esavo.fi/maakuntaohjelma. 5.5.2014. Regulations on design and environmental policies http://www.findacha.ru/faq/category/build/ accessed on 27th April, 2014. Regulations on purchase of property http://www.villasuomi.ru/purchase.php accessed on 25th April, 2014. Regulations on second home ownership http://www.profinland.ru/nedvizhimost.html accessed on 25thApril, 2014. Regulations on second homes http://inostrannik.ru/info/finlyandiya.html Regulations on second homes http://tillvaxtanalys.se/download/18.69e9bee013b03a9470a45a/1353075304325/ English_summary_Rural_Housing.pdf . accessed on 23rd April ,2014. Saarinen, J., 2004. Tourism and touristic representations of nature. In: Dew, A.A., Hall, C.M., Williams, A.M. (Eds.), A Companion to Tourism. Blackwell Publishing, Malden. Saaristoasiain neuvottelukunta (2006). Mökkiläiset kuntapalvelujen käyttäjinä. Sisäasiainministeriön julkaisuja 24:2006. <https://www.tem.fi/alueiden_kehittaminen/kansallinen_alueiden_kehittaminen/ saaristopolitiikka/julkaisut_selvitykset_ja_esitteet> Savonlinnan innovaatiokeskus (2010). Regional analysis of Saimaa waterways system and Savonlinna Region. <http://www.waterways-forward.eu/wp content/uploads/gravity_forms/1/2010/11/PA%208%20Regional%20analysis.pd f> Sheller, M. and Urry, J.,ed. 2004. Tourism mobilities: places to play, places in play. London: Routledge. The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A 38, 207–26. Statistics Finland (2013a). Free time residences 2012. <http://www.stat.fi/til/rakke/2012/rakke_2012_2013-05-24_kat_001_en.html. 5.5.2014.> Statistics Finland (2013b). Mökkeilystä vastapainoa arjen asumiselle. <http://www.stat.fi/artikkelit/2013/art_2013-06-03_002.html. 5.5.2014> Statistics Finland (2014). Väestörakenne 2014. <http://193.166.171.75/database/StatFin/vrm/vaerak/vaerak_fi.asp. 4.5.2014>. Statistics Finland. 2011. Time use survey: Time Use (26 categories) in autumn 1979, 1987 1999 and 2009. Retrieved from http://www.stat.fi/til/akay/index_en.html Talbot, H. & P. Courtney (2011). Improved urban-rural linkages as an EU rural development policy measure. International conference 2011. <http://www.regionalstudies.org/uploads/conferences/presentations/international -conference-2011/talbot.pdf> Velvin J. (2013) The impact of second home tourism on local economic development in rural areas in Norway Vepsäläinen & Pitkänen (2010). Second home countryside. Representations of the rural in Finnish popular discourses. Journal of Rural Studies 26 (2010) 194– 204. Vepsalainen M., Pitkanen K. (2009) Second home countryside. Representations of the rural in Finnish popular discourses Vepsäläinen, M., M. Hiltunen & K. Pitkänen (2008): Foreseeing Trends and Ecosocial Impacts of Second Home Tourism in Finland University of Joensuu Centre for Tourism Studies. The 17th Nordic Symposium in Tourism and Hospitality Research Lillehammer, September 25-28, 2008 <https://www.uef.fi/documents/1145891/1362835/Trends+and+Impacts+Lilleha mmer+presentation.pdf/be555f73-4af2-4506-afe2-ebac3f00bd3f> Wolfe, R.I (1977). Summer cottages in Ontario: purpose-built for an inessential purpose. In: Coppock, J.T. (Ed.), Second Homes: Curse or Blessing? Pergamon Press, Oxford http://tillvaxtanalys.se/download/18.69e9bee013b03a9470a45a/1353075304325/ English_summary_Rural_Housing.pdf