578 R - International Law Students Association

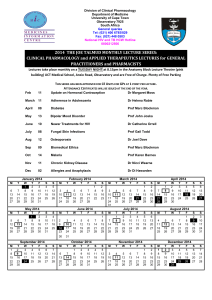

advertisement