3 - Sociologický ústav AV ČR, vvi

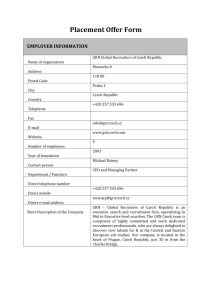

advertisement