Participants - welearnsomething

advertisement

Learn Something New:

Experiential Course on Facilitation

for IUCN Young Professionals and others

Course workbook containing agenda, rapporteur notes,

and hand-outs from all six modules

May-August 2007

Introduction and Justification

The Learning Team wants to help IUCN to be acknowledged as a learning organization which,

rather than reinventing wheels, is creating and sharing knowledge through effective peer-learning

mechanisms across all parts of the world.

As part of this ambitious undertaking, the team proposes an experiential, peer-learning course on

the various aspects of facilitating effective events for IUCN HQ’s Young Professionals plus all

others interested. Young professional Julie Griffin will coordinate this, in collaboration with the

Learning Team.

Concept

The course will run over several weeks, with a one to two hour session every two weeks covering

a particular aspect of facilitation. You will facilitate and lead most of the sessions - because

learning-by-doing is much more effective than just listening to a how-to session - with assistance

from the Learning Team and other participants in the preparatory stages. (Working in teams to

prepare for the sessions will be part of the training and practice.) Co-facilitation of sessions will

also be an option.

Upon successful completion of the course, you will belong to an internal community of practice

and be able to offer your facilitation services to any programme in IUCN in need of help to

design and facilitate events for maximum effectiveness. Your details will be made available on

the CEC portal, along with a new resource bank of facilitation tools and tips.

Objectives

Become more familiar with the concept of facilitation

Explore the characteristics of effective events

Become more familiar with practical tools for designing and managing events

Improve understanding and practice a range of facilitation techniques and tools

Learn new skills to deal with challenging situations

Develop an increased ability to support organizational change

Increase confidence and energy to take on greater leadership roles

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 2

3/9/2016

Suggested curriculum for the course

Week

Topic

April 25

Introducing facilitation and principles for further sessions

Purpose, value-added, and application (led by Gillian)

May 9

Pre-event preparation

Working with organizers to define purpose; set the agenda; and consider

pre-event communication and activities with participants

May 23

Establishing means for reflection and learning

Determining appropriate tools and practices for evaluating the success of

events and learning about what could be done differently; giving and

receiving feedback

June 6

Framing space and context

Choosing and setting up the space; taking cultural considerations into

account; welcoming participants and introducing sessions

June 20

Experimenting with specific facilitation tools and techniques # 1

Matching activities and needs

June 27

Experimenting with specific facilitation tools and techniques # 2

Matching activities and needs

Follow up

Putting our learning into practice

Invite colleagues/programmes to include us (in small groups) in designing

and facilitating short events (2 hours each time)

30 min preparation (facilitators only)

1 hour doing an activity

30 minutes de-briefing (facilitators only)

Please consider:

Are you willing and able to commit to one or two hours every two weeks (over lunch)?

Are you willing to (co-)facilitate one of the sessions, dedicating one hour of preparation

time and some time after the session to write up your reflections in a learning story?

What topics do you recommend adding to the list above?

Any other suggestions?

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 3

3/9/2016

Module 1: Introduction

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 4

3/9/2016

Agenda - Module 1 - Thursday 26 April

Time

Event

Content

15:30

Session 1

Objectives,

Introduction and

Context Setting

(Main Conference room)

16:00

Session 2

What is Facilitation?

(Main Conference room)

16:35

Session 3

5 Useful

Models/Theories for

Facilitators

(Main Conference room)

17:00

Session 4

Next Module and

Check Out

Facilitator/

Chair

Introduction to course, its objectives and

expected outcomes, Gillian Martin

Mehers, Conservation Learning

Coordinator. (5 min)

Schedule for Module 1 and participant

introductions – Learning zones – 2 part

discussion 1) Pair introductions (10 min)

2) Group discussion (10 min)

Roots and definitions (5 min)

Two inter-related components (5 min)

Qualities of a good facilitator –

visualization/objectification exercise (15

min)

Core skills of a good facilitator (5 min)

Finding F’s exercise – Egon Brunswick

Lens Model (5 min)

Four other models – small group work

and presentation (12 min work, 3 min

each present)

Discussion – individual work

Briefing of next week and roles (2 min)

Check out, Julie Griffin (10 min)

Gillian Martin

Mehers

G. Martin

Mehers

G. Martin

Mehers

G. Martin

Mehers

Julie Griffin

Rapporteur Notes – Module 1

(Notes by Julie Griffin, April 2007)

Session 1: Objectives, Introduction and context setting

Gillian introduced what the course will be about and how it will work.

We used the technique of pair discussions during which each pair discussed what they needed to

be ready to learn. The following stood out to me as elements of a successful context for

learning:

-

the right environment/atmosphere is especially important (e.g. - some said a casual

setting)

an interest in the topic

outside factors (i.e. – stress from work can inhibit one’s ability to focus and learn)

an inspirational person or teacher running the course

relevance to one’s own work or interest (and an ability to see how the new material can

be applied)

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 5

3/9/2016

Seeing this list was a good reminder of all the elements that a facilitator, teacher or coach must

take care of in order to create the most enabling learning situation for participants.

Gillian also talked about comfort zones and drew a diagram to explain the idea that each

individual has three zones in which s/he can operate: a Comfort zone, a Eustress zone (good

stress), and a Distress zone (bad stress). Each person has different sized zones, but in this course

we want to operate in the Eustress zone.

Session 2: What is facilitation?

In this session we talked about the definition of this concept by looking at the roots of the word

facilitate. Gillian provided useful definitions which I’ve copied here:

•

•

Facilitation is the skill, the art of guiding others to solve their own problems and

achieve their objectives without simply giving advice or offering solutions.

A Facilitator provides the structure and process – enabling groups to function

effectively and make high-quality decisions.

We also talked about the different types of people that can be running a meeting, since they are

not all necessarily facilitators. Gillian expresses this as a continuum of low to high content input,

and low to high process input.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 6

3/9/2016

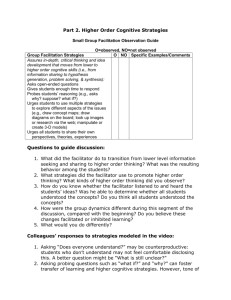

This diagram helps to think about when a facilitator is needed. It also highlights that a facilitator

does not need to be an expert in the subject matter of the meeting. Facilitating is a balance

between task (taking care of the objectives of the meeting), and maintenance (managing the

process of how the meeting is running).

The next activity we did was an objectification/visualization activity: we broke into 4 groups

and each group drew a picture of the qualities of a good facilitator. The photos of these will be

added to these notes soon, but for now I’ll cite a few comments from the explanation and

discussion that we had while looking at each drawing:

-

recurring themes: listening skills, ability to synthesize ideas, creativity

conflict can be a good thing

a facilitator can sometime say “no”, but if the facilitator can create a group dynamic

where participants control the group themselves, that is even better

qualities the whole group did not agree upon:

o Should a facilitator be charismatic and draw attention to himself?

o Should a facilitator ever say no to a person or their ideas?

o Should a facilitator be the center of attention?

Gillian also listed these other core skills for a facilitator:

• Route Map for creating a facilitated event including defining the purpose, process and

anticipated outcomes

• Techniques for engaging the key stakeholders

• Creating a climate for success

• Managing the process

• Maintaining direction

• Monitoring progress

• Managing conflict

• Developing action plans

• Reviewing progress against anticipated outcomes

• Ensuring the momentum from a significant event is translated into action

Session 3: 5 Useful Models/Theories for Facilitators

Finally, we did a few small exercises to help us consider the lens through which we perceive any

situation. The Egon Brunswick exercise demonstrates this by having the group read a slide and

count the “F’s” in the text. The facilitator then asks who counted 1 F, 2 Fs, 3 Fs and so on. It is

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 7

3/9/2016

apparent that everyone did not count the same way! The group is asked to do it again, and still

the answers do not converge. It shows that people have different ways of reading, different

reading speeds, and even different reactions to how instructions are given.

In summary, the Brunswick lens theory says that your values, beliefs, rules, assumptions, life

experiences, etc, will influence your perceptions, understanding and meaning.

Because we ran out of time at the end, each person was given the last activity as homework.

Gillian distributed copies of a few traditional models to explain facilitation and asked each person

to read their model and try to apply it or observe it in action at work. We will report back at

Module 2 on May 10th. The models were: Kolb’s learning cycle, Johari window, The Ladder of

Inference, and Tuckmans’ model of group dynamics.

The day closed with a review of what was covered, in particular the tools that were used to run

the session. This list is on the wiki page.

Five Useful Models for Facilitators Expanded

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Kolb Learning Cycle

Johari Window

Ladder of Inference

Tuckman’s Model of Group Dynamics

Brunswick (to add)

Model 1: Kolb’s Learning Cycle (and Styles)

Kolb (1984) provides one of the most useful descriptive models of the adult learning process

available, inspired by the work of Kurt Lewin.

A way of using Kolb's learning styles is a cycle whereby we learn. This is different from Kolb's

styles which state that people have preferred static positions regarding these.

Experiencing

Experimenting

Reflecting

Theorizing

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 8

3/9/2016

i. Experiencing

First of all, we have an experience. Most experiences are not worth further movement on the

cycle as we are already familiar with them and they need no further interpretation and hence no

need for learning.

ii. Reflecting

Having experienced something which does not fit well into our current system of

understanding, we then have to stop and think harder about what it really means. This

reflection is typically a series of attempts to fit the experience to memories and our internal

models (or schemata).

iii. Theorizing

When we find that we cannot fit what we have experienced into any of our memories or

internal models, then we have to build new models. This theorizing gives us a possible answer

to our puzzling experiences.

iv. Experimenting

After building a theoretical model, the next step is to prove it in practice, either in 'real time' or

by deliberate experimentation in some safe arena. If the model does not work, then we go

through the loop again, reflecting on what happened and either adjusting the model or building

a new one.

So what?

So help people learn by giving them experiences, helping them reflect and build internal models,

and then giving them the means of trying out those models to see if they work in practice.

Taken from: http://changingminds.org/explanations/learning/learning_cycle.htm

Original source: Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential Learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

David Kolb has defined one of the most commonly used models of learning. As in the diagram

below, it is based on two preference dimensions, giving four different styles of learning.

Two Preference dimensions

Concrete

Experience

ACCOMODATORS

DIVERGERS

^

Perception

|

Active

Experimentation

<------

-- Processing --------

------>

Reflective

Observation

|

|

V

CONVERGERS

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Abstract

conceptualizatio

Page 9

ASSIMILATORS

3/9/2016

A. Perception dimension

In the vertical Perception dimension, people will have a preference along the continuum

between:

Concrete experience: Looking at things as they are, without any change, in raw detail.

Abstract conceptualization: Looking at things as concepts and ideas, after a degree of

processing that turns the raw detail into an internal model.

People who prefer concrete experience will argue that thinking about something changes it,

and that direct empirical data is essential. Those who prefer abstraction will argue that meaning

is created only after internal processing and that idealism is a more real approach.

This spectrum is very similar to the Jungian scale of Sensing vs. Intuiting.

B. Processing dimension

In the horizontal Processing dimension, people will take the results of their Perception and

process it in preferred ways along the continuum between:

Active experimentation: Taking what they have concluded and trying it out to prove that it

works.

Reflective observation: Taking what they have concluded and watching to see if it works.

Four learning styles

The experimenter, like the concrete experiencer, takes a hands-on route to see if their ideas will

work, whilst the reflective observers prefer to watch and think to work things out.

1. Divergers (Concrete experiencer/Reflective observer)

Divergers take experiences and think deeply about them, thus diverging from a single

experience to multiple possibilities in terms of what this might mean.

They like to ask 'why', and will start from detail to constructively work up to the big

picture.

They enjoy participating and working with others but they like a calm ship and fret

over conflicts.

They are generally influenced by other people and like to receive constructive

feedback.

They like to learn via logical instruction or hands-one exploration with conversations

that lead to discovery.

2. Convergers (Abstract conceptualization/Active experimenter)

Convergers think about things and then try out their ideas to see if they work in

practice.

They like to ask 'how' about a situation, understanding how things work in practice.

They like facts and will seek to make things efficient by making small and careful

changes.

They prefer to work by themselves, thinking carefully and acting independently.

They learn through interaction and computer-based learning is more effective with

them than other methods.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 10

3/9/2016

3. Accomodators (Concrete experiencer/Active experimenter)

Accommodators have the most hands-on approach, with a strong preference for doing

rather than thinking.

They like to ask 'what if?' and 'why not?' to support their action-first approach.

They do not like routine and will take creative risks to see what happens.

They like to explore complexity by direct interaction and learn better by themselves

than with other people.

As might be expected, they like hands-on and practical learning rather than lectures.

4. Assimilators (Abstract conceptualizer/Reflective observer)

Assimilators have the most cognitive approach, preferring to think than to act.

They ask 'What is there I can know?' and like organized and structured understanding.

They prefer lectures for learning, with demonstrations where possible, and will respect

the knowledge of experts. They will also learn through conversation that takes a logical

and thoughtful approach.

They often have a strong control need and prefer the clean and simple predictability of

internal models to external messiness.

The best way to teach an assimilator is with lectures that start from high-level concepts

and work down to the detail. Give them reading material, especially academic stuff and

they'll gobble it down. Do not teach through play with them as they like to stay

serious.

So what?

So design learning for the people you are working with. If you cannot customize the design for

specific people, use varied styles of delivery to help everyone learn. It can also be useful to

describe this model to people, both to help them understand how they learn and also so they

can appreciate that some of your delivery will for others more than them (and vice versa).

http://changingminds.org/explanations/learning/kolb_learning.htm

David Kolb’s own website: http://www.learningfromexperience.com/

(David Kolb, Professor of Organizational Development, Case Western Reserve, Cleveland, Ohio,

USA)

More on this: http://www.learningandteaching.info/learning/experience.htm

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 11

3/9/2016

Model 2: Johari Window

The Johari Window model is a simple and useful tool for illustrating and improving selfawareness, and mutual understanding between individuals within a group. The Johari Window

tool can also be used to assess and improve a group's relationship with other groups. The Johari

Window model was developed by American psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham in the

1950's, while researching group dynamics. Today the Johari Window model is especially relevant

due to modern emphasis on, and influence of, 'soft' skills, behaviour, empathy, cooperation,

inter-group development and interpersonal development.

Over the years, alternative Johari Window terminology has been developed and adapted by other

people - particularly leading to different descriptions of the four regions, hence the use of

different terms in this explanation. Don't let it all confuse you - the Johari Window model is

really very simple indeed.

Interestingly, Luft and Ingham called their Johari Window model 'Johari' after combining their

first names, Joe and Harry. In early publications the word actually appears as 'JoHari'. The Johari

Window soon became a widely used model for understanding and training self-awareness,

personal development, improving communications, interpersonal relationships, group dynamics,

team development and inter-group relationships.

The Johari Window model is also referred to as a 'disclosure/feedback model of self awareness',

and by some people an 'information processing tool'. The Johari Window actually represents

information - feelings, experience, views, attitudes, skills, intentions, motivation, etc - within or

about a person - in relation to their group, from four perspectives, which are described below.

The Johari Window model can also be used to represent the same information for a group in

relation to other groups. Johari Window terminology refers to 'self' and 'others': 'self' means

oneself, ie, the person subject to the Johari Window analysis. 'Others' means other people in the

person's group or team.

The four Johari Window perspectives are called 'regions' or 'areas' or 'quadrants'. Each of these

regions contains and represents the information - feelings, motivation, etc - known about the

person, in terms of whether the information is known or unknown by the person, and whether

the information is known or unknown by others in the group.

The Johari Window's four regions, (areas, quadrants, or perspectives) are as follows, showing the

quadrant numbers and commonly used names:

1. what is known by the person about him/herself and is also known by others - open

area, open self, free area, free self, or 'the arena'

2. what is unknown by the person about him/herself but which others know - blind area,

blind self, or 'blindspot'

3. what the person knows about him/herself that others do not know - hidden area,

hidden self, avoided area, avoided self or 'facade'

4. what is unknown by the person about him/herself and is also unknown by others unknown area or unknown self

Like some other behavioural models (eg, Tuckman, Hersey/Blanchard), the Johari Window is

based on a four-square grid - the Johari Window is like a window with four 'panes'. Here's how

the Johari Window is normally shown, with its four regions.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 12

3/9/2016

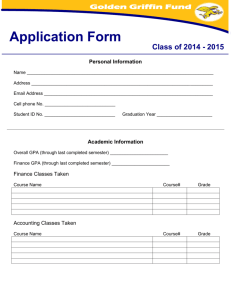

This is the standard representation of

the Johari Window model, showing

each quadrant the same size.

The Johari Window 'panes' can be

changed in size to reflect the relevant

proportions of each type of

'knowledge' of/about a particular

person in a given group or team

situation.

In new groups or teams the open free

space for any team member is small

(see the Johari Window new team

member example below) because

shared awareness is relatively small.

As the team member becomes better

established and known, so the size of

the team member's open free area

quadrant increases. See the Johari

Window established team member

example below.

Johari Window Model - Explanation of the Four Regions

Refer to the free detailed Johari Window model diagram in the free resources section - print a

copy and it will help you to understand what follows.

Johari quadrant 1 - 'open self/area' or 'free area' or 'public

area', or 'arena'

Johari region 1 is also known as the 'area of free activity'. This is the information about the

person - behaviour, attitude, feelings, emotion, knowledge, experience, skills, views, etc - known

by the person ('the self') and known by the group ('others').

The aim in any group should always be to develop the 'open area' for every person,

because when we work in this area with others we are at our most effective and

productive, and the group is at its most productive too. The open free area, or 'the

arena', can be seen as the space where good communications and cooperation occur,

free from distractions, mistrust, confusion, conflict and misunderstanding.

Established team members logically tend to have larger open areas than new team members.

New team members start with relatively small open areas because relatively little knowledge

about the new team member is shared. The size of the open area can be expanded horizontally

into the blind space, by seeking and actively listening to feedback from other group members.

This process is known as 'feedback solicitation'. Also, other group members can help a team

member expand their open area by offering feedback, sensitively of course. The size of the open

area can also be expanded vertically downwards into the hidden or avoided space by the person's

disclosure of information, feelings, etc about him/herself to the group and group members.

Also, group members can help a person expand their open area into the hidden area by asking

the person about him/herself.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 13

3/9/2016

Managers and team leaders can play an important role in facilitating feedback and disclosure

among group members, and in directly giving feedback to individuals about their own blind

areas. Leaders also have a big responsibility to promote a culture and expectation for open,

honest, positive, helpful, constructive, sensitive communications, and the sharing of knowledge

throughout their organization. Top performing groups, departments, companies and

organizations always tend to have a culture of open positive communication, so encouraging the

positive development of the 'open area' or 'open self' for everyone is a simple yet fundamental

aspect of effective leadership.

Johari quadrant 2 - 'blind self' or 'blind area' or 'blindspot'

Johari region 2 is what is known about a person by others in the group, but is unknown by the

person him/herself. By seeking or soliciting feedback from others, the aim should be to reduce

this area and thereby to increase the open area (see the Johari Window diagram below), ie, to

increase self-awareness. This blind area is not an effective or productive space for individuals or

groups. This blind area could also be referred to as ignorance about oneself, or issues in which

one is deluded. A blind area could also include issues that others are deliberately withholding

from a person. We all know how difficult it is to work well when kept in the dark. No-one works

well when subject to 'mushroom management'. People who are 'thick-skinned' tend to have a

large 'blind area'.

Group members and managers can take some responsibility for helping an individual to reduce

their blind area - in turn increasing the open area - by giving sensitive feedback and encouraging

disclosure. Managers should promote a climate of non-judgemental feedback, and group

response to individual disclosure, which reduces fear and therefore encourages both processes to

happen. The extent to which an individual seeks feedback, and the issues on which feedback is

sought, must always be at the individual's own discretion. Some people are more resilient than

others - care needs to be taken to avoid causing emotional upset. The process of soliciting

serious and deep feedback relates to the process of 'self-actualization' described in Maslow's

Hierarchy of Needs development and motivation model.

Johari quadrant 3 - 'hidden self' or 'hidden area' or 'avoided

self/area' or 'facade'

Johari region 3 is what is known to ourselves but kept hidden from, and therefore unknown, to

others. This hidden or avoided self represents information, feelings, etc, anything that a person

knows about him/self, but which is not revealed or is kept hidden from others. The hidden area

could also include sensitivities, fears, hidden agendas, manipulative intentions, secrets - anything

that a person knows but does not reveal, for whatever reason. It's natural for very personal and

private information and feelings to remain hidden, indeed, certain information, feelings and

experiences have no bearing on work, and so can and should remain hidden. However, typically,

a lot of hidden information is not very personal, it is work- or performance-related, and so is

better positioned in the open area.

Relevant hidden information and feelings, etc, should be moved into the open area through the

process of 'disclosure'. The aim should be to disclose and expose relevant information and

feelings - hence the Johari Window terminology 'self-disclosure' and 'exposure process', thereby

increasing the open area. By telling others how we feel and other information about ourselves

we reduce the hidden area, and increase the open area, which enables better understanding,

cooperation, trust, team-working effectiveness and productivity. Reducing hidden areas also

reduces the potential for confusion, misunderstanding, poor communication, etc, which all

distract from and undermine team effectiveness.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 14

3/9/2016

Organizational culture and working atmosphere have a major influence on group members'

preparedness to disclose their hidden selves. Most people fear judgement or vulnerability and

therefore hold back hidden information and feelings, etc, that if moved into the open area, ie

known by the group as well, would enhance mutual understanding, and thereby improve group

awareness, enabling better individual performance and group effectiveness.

The extent to which an individual discloses personal feelings and information, and the issues

which are disclosed, and to whom, must always be at the individual's own discretion. Some

people are more keen and able than others to disclose. People should disclose at a pace and

depth that they find personally comfortable. As with feedback, some people are more resilient

than others - care needs to be taken to avoid causing emotional upset. Also as with soliciting

feedback, the process of serious disclosure relates to the process of 'self-actualization' described

in Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs development and motivation model.

Johari quadrant 4 - 'unknown self' or 'area of unknown activity'

or 'unknown area'

Johari region 4 contains information, feelings, latent abilities, aptitudes, experiences etc, that are

unknown to the person him/herself and unknown to others in the group. These unknown

issues take a variety of forms: they can be feelings, behaviours, attitudes, capabilities, aptitudes,

which can be quite close to the surface, and which can be positive and useful, or they can be

deeper aspects of a person's personality, influencing his/her behaviour to various degrees. Large

unknown areas would typically be expected in younger people, and people who lack experience

or self-belief.

Examples of unknown factors are as follows, and the first example is particularly relevant and

common, especially in typical organizations and teams:

an ability that is under-estimated or un-tried through lack of opportunity,

encouragement, confidence or training

a natural ability or aptitude that a person doesn't realise they possess

a fear or aversion that a person does not know they have

an unknown illness

repressed or subconscious feelings

conditioned behaviour or attitudes from childhood

The processes by which this information and knowledge can be uncovered are various, and can

be prompted through self-discovery or observation by others, or in certain situations through

collective or mutual discovery, of the sort of discovery experienced on outward bound courses

or other deep or intensive group work. Counselling can also uncover unknown issues, but this

would then be known to the person and by one other, rather than by a group.

Whether unknown 'discovered' knowledge moves into the hidden, blind or open area depends

on who discovers it and what they do with the knowledge, notably whether it is then given as

feedback, or disclosed. As with the processes of soliciting feedback and disclosure, striving to

discover information and feelings in the unknown is relates to the process of 'self-actualization'

described in Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs development and motivation model.

Again as with disclosure and soliciting feedback, the process of self discovery is a sensitive one.

The extent and depth to which an individual is able to seek out discover their unknown feelings

must always be at the individual's own discretion. Some people are more keen and able than

others to do this.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 15

3/9/2016

Uncovering 'hidden talents' - that is unknown aptitudes and skills, not to be confused with

developing the Johari 'hidden area' - is another aspect of developing the unknown area, and is

not so sensitive as unknown feelings. Providing people with the opportunity to try new things,

with no great pressure to succeed, is often a useful way to discover unknown abilities, and

thereby reduce the unknown area.

Managers and leaders can help by creating an environment that encourages self-discovery, and to

promote the processes of self discovery, constructive observation and feedback among team

members. It is a widely accepted industrial fact that the majority of staff in any organization are

at any time working well within their potential. Creating a culture, climate and expectation for

self-discovery helps people to fulfil more of their potential and thereby to achieve more, and to

contribute more to organizational performance.

A note of caution about Johari region 4: The unknown area could also include repressed or

subconscious feelings rooted in formative events and traumatic past experiences, which can stay

unknown for a lifetime. In a work or organizational context the Johari Window should not be

used to address issues of a clinical nature. Useful references are Arthur Janov's seminal book

The Primal Scream (read about the book here), and Transactional Analysis.

© alan chapman adaptation, review and code 1995-2006, based on ingham and luft's original

johari window concept.

http://www.businessballs.com/johariwindowmodel.htm

Interactive johari’s window - http://kevan.org/johari

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 16

3/9/2016

Model 3: The Ladder of Inference

We are so skilled at thinking that we jump up the ladder without knowing it:

We tacitly register some data and ignore other data.

We impose our own interpretations on these data and draw conclusions from them.

We lose sight of how we do this because we do not think about our thinking.

Hence, our conclusions feel so obvious to us that we see no need to retrace the steps we

took from the data we selected to the conclusions we reached.

The contexts we are in, our assumptions, and our values channel how we jump up the

ladder:

Our models of how the world works and our repertoire of actions influence the data we

select, the interpretations we make, and the conclusions we draw.

Our conclusions lead us to act in ways that produce results that feed back to reinforce

(usually) our contexts and assumptions.

Our skill at reasoning is both essential and gets us in trouble:

If we thought about each inference we made, life would pass us by.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 17

3/9/2016

But people can and do reach different conclusions. When they view their conclusions as

obvious, no one sees a need to say how they reached them.

When people disagree, they often hurl conclusions at each other from the tops of their

respective ladders.

This makes it hard to resolve differences and to learn from one another.

http://www.actiondesign.com/resources/concepts/ladder_intro.htm

The Ladder of Inference

Excerpt from The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook. Copyright 1994 by Peter M. Senge, Art Kleiner,

Charlotte Roberts, Richard B. Ross, and Bryan J. Smith. Reprinted with permission.

We live in a world of self-generating beliefs which remain largely untested. We adopt those

beliefs because they are based on conclusions, which are inferred from what we observe, plus

our past experience. Our ability to achieve the results we truly desire is eroded by our feelings

that:

Our beliefs are the truth.

The truth is obvious.

Our beliefs are based on real data.

The data we select are the real data.

For example: I am standing before the executive team, making a presentation. They all seem

engaged and alert, except for Larry, at the end of the table, who seems bored out of his mind.

He turns his dark, morose eyes away from me and puts his hand to his mouth. He doesn't ask

any questions until I'm almost done, when he breaks in: "I think we should ask for a full report."

In this culture, that typically means, "Let's move on." Everyone starts to shuffle their papers and

put their notes away. Larry obviously thinks that I'm incompetent -- which is a shame, because

these ideas are exactly what his department needs. Now that I think of it, he's never liked my

ideas. Clearly, Larry is a power-hungry jerk. By the time I've returned to my seat, I've made a

decision: I'm not going to include anything in my report that Larry can use. He wouldn't read it,

or, worse still, he'd just use it against me. It's too bad I have an enemy who's so prominent in the

company.

In those few seconds before I take my seat, I have climbed up what Chris Argyris calls a "ladder

of inference," -- a common mental pathway of increasing abstraction, often leading to misguided

beliefs:

I started with the observable data: Larry's comment, which is so self- evident that it

would show up on a videotape recorder . . .

. . . I selected some details about Larry's behavior: his glance away from me and apparent

yawn. (I didn't notice him listening intently one moment before) . . .

. . . I added some meanings of my own, based on the culture around me (that Larry

wanted me to finish up) . . .

. . . I moved rapidly up to assumptions about Larry's current state (he's bored) . . .

. . . and I concluded that Larry, in general, thinks I'm incompetent. In fact, I now believe

that Larry (and probably everyone whom I associate with Larry) is dangerously opposed

to me . . .

. . . thus, as I reach the top of the ladder, I'm plotting against him.

It all seems so reasonable, and it happens so quickly, that I'm not even aware I've done it.

Moreover, all the rungs of the ladder take place in my head. The only parts visible to anyone else

are the directly observable data at the bottom, and my own decision to take action at the top.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 18

3/9/2016

The rest of the trip, the ladder where I spend most of my time, is unseen, unquestioned, not

considered fit for discussion, and enormously abstract. (These leaps up the ladder are sometimes

called "leaps of abstraction.")

I've probably leaped up that ladder of inference many times before. The more I believe that

Larry is an evil guy, the more I reinforce my tendency to notice his malevolent behavior in the

future. This phenomenon is known as the "reflexive loop": our beliefs influence what data we

select next time. And there is a counterpart reflexive loop in Larry's mind: as he reacts to my

strangely antagonistic behavior, he's probably jumping up some rungs on his own ladder. For no

apparent reason, before too long, we could find ourselves becoming bitter enemies.

Larry might indeed have been bored by my presentation -- or he might have been eager to read

the report on paper. He might think I'm incompetent, he might be shy, or he might be afraid to

embarrass me. More likely than not, he has inferred that I think he's incompetent. We can't

know, until we find a way to check our conclusions.

Unfortunately, assumptions and conclusions are particularly difficult to test. For instance,

suppose I wanted to find out if Larry really thought I was incompetent. I would have to pull him

aside and ask him, "Larry, do you think I'm an idiot?" Even if I could find a way to phrase the

question, how could I believe the answer? Would I answer him honestly? No, I'd tell him I

thought he was a terrific colleague, while privately thinking worse of him for asking me.

Now imagine me, Larry, and three others in a senior management team, with our untested

assumptions and beliefs. When we meet to deal with a concrete problem, the air is filled with

misunderstandings, communication breakdowns, and feeble compromises. Thus, while our

individual IQs average 140, our team has a collective IQ of 85.

The ladder of inference explains why most people don't usually remember where their deepest

attitudes came from. The data is long since lost to memory, after years of inferential leaps.

Sometimes I find myself arguing that "The Republicans are so-and-so," and someone asks me

why I believe that. My immediate, intuitive answer is, "I don't know. But I've believed it for

years." In the meantime, other people are saying, "The Democrats are so-and-so," and they can't

tell you why, either. Instead, they may dredge up an old platitude which once was an assumption.

Before long, we come to think of our longstanding assumptions as data ("Well, I know the

Republicans are such-and-such because they're so-and-so"), but we're several steps removed

from the data.

Using the Ladder of Inference

You can't live your life without adding meaning or drawing conclusions. It would be an

inefficient, tedious way to live. But you can improve your communications through reflection,

and by using the ladder of inference in three ways:

Becoming more aware of your own thinking and reasoning (reflection);

Making your thinking and reasoning more visible to others (advocacy);

Inquiring into others' thinking and reasoning (inquiry).

Once Larry and I understand the concepts behind the "ladder of inference," we have a safe way

to stop a conversation in its tracks and ask several questions:

What is the observable data behind that statement?

Does everyone agree on what the data is?

Can you run me through your reasoning?

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 19

3/9/2016

How did we get from that data to these abstract assumptions?

When you said "[your inference]," did you mean "[my interpretation of it]"?

I can ask for data in an open-ended way: "Larry, what was your reaction to this presentation?" I

can test my assumptions: "Larry, are you bored?" Or I can simply test the observable data:

"You've been quiet, Larry." To which he might reply: "Yeah, I'm taking notes; I love this stuff."

Note that I don't say, "Larry, I think you've moved way up the ladder of inference. Here's what

you need to do to get down." The point of this method is not to nail Larry (or even to diagnose

Larry), but to make our thinking processes visible, to see what the differences are in our

perceptions and what we have in common. (You might say, "I notice I'm moving up the ladder

of inference, and maybe we all are. What's the data here?")

This type of conversation is not easy. For example, as Chris Argyris cautions people, when a fact

seems especially self-evident, be careful. If your manner suggests that it must be equally selfevident to everyone else, you may cut off the chance to test it. A fact, no matter how obvious it

seems, isn't really substantiated until it's verified independently -- by more than one person's

observation, or by a technological record (a tape recording or photograph).

Embedded into team practice, the ladder becomes a very healthy tool. There's something

exhilarating about showing other people the links of your reasoning. They may or may not agree

with you, but they can see how you got there. And you're often surprised yourself to see how

you got there, once you trace out the links.

http://www.solonline.org/pra//tool/ladder.html

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 20

3/9/2016

Model 4: Tuckmans’ Model of Group

Dynamics

Forming - Storming - Norming - Performing

This model was first developed by Bruce Tuckman in 1965. It is one of the best known team

development theories and has formed the basis of many further ideas since its conception.

Tuckman's theory focuses on the way in which a team tackles a task from the initial formation of

the team through to the completion of the project. Tuckman later added a fifth phase;

Adjourning and Transforming to cover the finishing of a task. Tuckman's theory is particularly

relevant to team building challenges as the phases are relevant to the completion of any task

undertaken by a team.

One of the very useful aspects of team building challenges contained within a short period of

time is that teams have an opportunity to observe their behaviour within a measurable time

frame. Often teams are involved in projects at work lasting for months or years and it can be

difficult to understand experiences in the context of a completed task.

Forming

The team is assembled and the task is allocated.

Team members tend to behave independently and although goodwill may exist they do

not know each other well enough to unconditionally trust one another.

Time is spent planning, collecting information and bonding.

Storming

The team starts to address the task suggesting ideas.

Different ideas may compete for ascendancy and if badly managed this phase can be

very destructive for the team.

Relationships between team members will be made or broken in this phase and some

may never recover.

In extreme cases the team can become stuck in the Storming phase.

If a team is too focused on consensus they may decide on a plan which is less effective

in completing the task for the sake of the team.

This carries its own set of problems. It is essential that a team has strong facilitative

leadership in this phase.

Norming

As the team moves out of the Storming phase they will enter the Norming phase.

This tends to be a move towards harmonious working practices with teams agreeing on

the rules and values by which they operate.

In the ideal situation teams begin to trust themselves during this phase as they accept

the vital contribution of each member to the team.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 21

3/9/2016

Team leaders can take a step back from the team at this stage as individual members

take greater responsibility.

The risk during the Norming stage is that the team becomes complacent and loses

either their creative edge or the drive that brought them to this phase.

Performing

Not all teams make it to the Performing phase, which is essentially an era of high

performance.

Performing teams are identified by high levels if independence, motivation, knowledge

and competence.

Decision making is collaborative and dissent is expected and encouraged as there will be

a high level of respect in the communication between team members.

Adjourning & Transforming

This is the final phase added by Tuckman to cover the end of the project and the break

up of the team.

Some call this phase Mourning, although this is a rather depressing way of looking at the

situation.

More enlightened managers have called Progressive Resources in to organise a

celebratory event at the end of a project and members of such a team will undoubtedly

leave the project with fond memories of their experience.

It should be noted that a team can return to any phase within the model if they

experience a change, for example a review of their project or goals or a change in

members of a team.

In a successful team when a member leaves or a new member joins the team will revert

to the Forming stage, but it may last for a very short time as the new team member is

brought into the fold

http://www.teambuilding.co.uk/Forming_Storming_Norming_Performing.html

(Note: Similar description but with more focus on leader’s role)

Bruce Tuckman's 1965 Forming Storming Norming

Performing team-development model

Dr Bruce Tuckman published his Forming Storming Norming Performing model in 1965. He

added a fifth stage, Adjourning, in the 1970's. The Forming Storming Norming Performing

theory is an elegant and helpful explanation of team development and behaviour. Similarities can

be seen with other models, such as Tannenbaum and Schmidt Continuum and especially with

Hersey and Blanchard's Situational Leadership® model, developed about the same time.

Tuckman's model explains that as the team develops maturity and ability, relationships establish,

and the leader changes leadership style. Beginning with a directing style, moving through

coaching, then participating, finishing delegating and almost detached. At this point the team

may produce a successor leader and the previous leader can move on to develop a new team.

This progression of team behaviour and leadership style can be seen clearly in the Tannenbaum

and Schmidt Continuum - the authority and freedom extended by the leader to the team

increases while the control of the leader reduces. In Tuckman's Forming Storming Norming

Performing model, Hersey's and Blanchard's Situational Leadership® model and in

Tannenbaum and Schmidt's Continuum, we see the same effect, represented in three ways.

The progression is:

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 22

3/9/2016

1.

2.

3.

4.

Forming

Storming

Norming

Performing

Features of each phase:

Forming - stage 1

High dependence on leader for guidance and direction. Little agreement on team aims other

than received from leader. Individual roles and responsibilities are unclear. Leader must be

prepared to answer lots of questions about the team's purpose, objectives and external

relationships. Processes are often ignored. Members test tolerance of system and leader. Leader

directs (similar to Situational Leadership® 'Telling' mode).

Storming - stage 2

Decisions don't come easily within group. Team members vie for position as they attempt to

establish themselves in relation to other team members and the leader, who might receive

challenges from team members. Clarity of purpose increases but plenty of uncertainties persist.

Cliques and factions form and there may be power struggles. The team needs to be focused on

its goals to avoid becoming distracted by relationships and emotional issues. Compromises may

be required to enable progress. Leader coaches (similar to Situational Leadership® 'Selling'

mode).

Norming - stage 3

Agreement and consensus is largely forms among team, who respond well to facilitation by

leader. Roles and responsibilities are clear and accepted. Big decisions are made by group

agreement. Smaller decisions may be delegated to individuals or small teams within group.

Commitment and unity is strong. The team may engage in fun and social activities. The team

discusses and develops its processes and working style. There is general respect for the leader

and some of leadership is more shared by the team. Leader facilitates and enables (similar to the

Situational Leadership® 'Participating' mode).

Performing - stage 4

The team is more strategically aware; the team knows clearly why it is doing what it is doing. The

team has a shared vision and is able to stand on its own feet with no interference or participation

from the leader. There is a focus on over-achieving goals, and the team makes most of the

decisions against criteria agreed with the leader. The team has a high degree of autonomy.

Disagreements occur but now they are resolved within the team positively and necessary changes

to processes and structure are made by the team. The team is able to work towards achieving the

goal, and also to attend to relationship, style and process issues along the way. team members

look after each other. The team requires delegated tasks and projects from the leader. The team

does not need to be instructed or assisted. Team members might ask for assistance from the

leader with personal and interpersonal development. Leader delegates and oversees (similar to

the Situational Leadership® 'Delegating' mode).

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 23

3/9/2016

Tuckman's fifth stage - Adjourning

Bruce Tuckman refined his theory around 1975 and added a fifth stage to the Forming,

Storming, Norming, Performing model - he called it Adjourning, which is also referred to as

Deforming and Mourning. Adjourning is arguably more of an adjunct to the original four stage

model rather than an extension - it views the group from a perspective beyond the purpose of

the first four stages. The Adjourning phase is certainly very relevant to the people in the group

and their well-being, but not to the main task of managing and developing a team, which is

clearly central to the original four stages.

Adjourning - stage 5

Tuckman's fifth stage, Adjourning, is the break-up of the group, hopefully when the task is

completed successfully, its purpose fulfilled; everyone can move on to new things, feeling good

about what's been achieved. From an organizational perspective, recognition of and sensitivity to

people's vulnerabilities in Tuckman's fifth stage is helpful, particularly if members of the group

have been closely bonded and feel a sense of insecurity or threat from this change. Feelings of

insecurity would be natural for people with high 'steadiness' attributes (as regards the 'four

temperaments' or DISC model) and with strong routine and empathy style (as regards the

Benziger thinking styles model, right and left basal brain dominance

http://www.businessballs.com/tuckmanformingstormingnormingperforming.htm

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 24

3/9/2016

Module 2: Giving and Receiving Feedback

and the Stages of the Facilitation Process

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 25

3/9/2016

Agenda – Module 2 – Thursday 10 May

Time

Event

Content

Facilitator/

Chair

15:30

Session 1

Check in

(Main Conference room)

Session 2

Giving and Receiving

Feedback

Quick check-in activity: Getting everyone

into the room. Visual check-in (10 min)

Sarah Gotheil

During this course, we will be having

participant facilitators take on pieces of

facilitation work. After each session, we

will take 5 minutes to give feedback on

their work.

In this session we will identify:

a) What kind of feedback we want and

b) How we wish to receive it (10 min).

Giving feedback to Sarah and Ivo (10

min)

Ivo Mulder

15:40

16:00

16:05

16:10

Session 3

Objectives of the Day,

Introduction to the

Module

Session 4

Stages of the

Facilitation Process

Introduction to Module 2, its objectives and

expected outcomes (5 min).

Gillian Martin

Mehers

Gillian Martin

Mehers

Session 5

Fishbowl Exercise

Focus on Stage 1:

Preparation

17:05

Session 6

Homework

17:15

Session 7

The Next Module and

Check Out

End of Session

17:30

Merja Murdoch

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Introduction to the stages of the

Facilitation process:

o Stage 1: Preparation

o Stage 2: Delivery; and

o Stage 3: Follow-Up (5 min)

Fishbowl Technique – Real life “Client”

and Facilitators discussion – “I have an

event coming up, can you help me

facilitate it?”

Fishbowl group discussion 10 minutes,

then observer observations (15 min).

Brainstorming design techniques for this

purpose (10 min) Rapporteur

Checklists – presentation and discussion

(10)

Review of homework: 5 Useful

Models/Theories for Facilitators - small

group discussion. How might we have

noticed application of our model in the

last hour and a half? (10 min)

Briefing: next week and roles (5 min)

Check out and reflections (10 min)

Page 26

Lizzie

Crudgington

Gillian Martin

Mehers

Merja Murdoch

Julie Griffin

3/9/2016

Rapporteur notes – Module 2

Agenda:

Module 2 - Agenda - Preparation.pdf

1) 'Please draw how you feel!'

This was the question Sarah posed in the 'check-in' session, asking each participant to take 5 minutes to

draw how they feel. Once done, because we were sat round in a square behind desks, everyone held up

their drawing to show the whole group. Any questions people had about individual drawings were posed

to the artist themselves, and there was some discussion about what we observed.

Observations

That in several cases, people who worked together or had spent time together that day had very similar

drawings (eg including the same features)

That the discussion would have been different if we had placed our drawings on the desks and walked

around them all, which was planned originally but changed due to the room set-up

That it helped both the group to understand how each other felt, and the facilitators to see if their plans

would work with this group on this day, and whether there was any individual or small group of participants

who might change the dynamic

That it cleared people's heads and helped them focus on the session ahead

2) 'How do you like your feedback?'

Giving and receiving feedback is an important part of a facilitated session, both for the group to feel part

of the process and for the facilitator to understand how their planning translated into actual running of the

session, and for everyone to see whether they had achieved their set goals.

Ivo facilitated a discussion on how people like to receive feedback, taking into consideration that we

would be doing this for all facilitators in the future sessions.

What: do you like to receive written or verbal feedback, in plenary or individually, right then or later?

How: do you like direct, honest feedback or something more diplomatic if it's in front of a group. If it's

individual do you like more honesty?

Group discussion around being a facilitator - we did this whilst giving feedback on the facilitators of this

session

- Clarity of instruction is crucial

- Timing is important and the facilitator should make sure it's on track

- It's good to focus on new ideas that are coming out in the group discussion and make sure the same

point isn't being repeated by different people (eg ask 'is this a new point to add or has it been covered?')

- Think about your body language - is it welcoming, relaxed but formal? Is your voice clear and potentially

slower if there are different languages in the room?

- Useful to ask for a scribe so the facilitator can focus entirely on the group

What and how to give feedback

What (ie what do you want the feedback to be on)

- Body language

- Body positioning in room

- Use of language (clarity / good choice of vocab?)

- Variety in tone of voice

- Clear instructions

- Good eye contact

- Connection, diversity of people and different parts of the room

- Time-keeping and good allocation of timing

- Matching of exercise to task

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 27

3/9/2016

How (ie how do you want that feedback to be delivered)

- Positive first, then any 'less positive' feedback should be framed as constructive, appreciative

- Honest

- Constructive recommendations and ways to improve

- Sincere

- Personal - ask the person what they want

Mechanisms

- some people preferred written feedback which can be more honest, can be kept, and can be revisited. It

can also be sent after the event rather than overloading with information

- some people preferred group discussion which can eliminate focusing too much on one individual's

feedback (which is very personal and could be skewed)

3) 'Where do I start?'

There are several stages a facilitator should go through when beginning to plan a session:

Preparation

o assessment of the situation

o discussion of contract of agreement between the client and facilitator

o education

Design

o consultation with relevant parties (attendees, organiser, experts)

Delivery

o rechecking of contract between parties, delivery of session

Follow-up with participants and organiser

4) 'What exactly do you want from me as a facilitator?'

We used the Fishbowl technique to simulate the discussion that might take place when a 'client'

approaches you to be their facilitator.

Observations

This is often described as a listening game, helping to obtain detail from a large group of people.

1. Our group chose one 'client' and three 'facilitators' to move their chairs into the centre of our circle,

facing inwards towards each other and therefore with their back to the group. The smaller

circle represents the 'fish', and the larger group is the 'fish-bowl' round the outside of the room, in this

situation, unable to

contribute but instead must focus on observing. For them this is a listening exercise.

2. The client first described one meeting they are overseeing in the near future, then the facilitators

questioned the client on the preparations etc, imagining that they had been asked to facilitate it. The fish

spoke amongst themselves with those outside the circle listening.

3. Near the end, someone in the outside circle told the group they only had 3 minutes left, and to consider

what details they had not retrieved that they wanted and what they should ask to ensure they understand

completely what the client wants.

Some good questions asked and what they helped show:

Who is coming, how many, what experience do they have and why are they coming / why is the client

organising the meeting? Has the group worked together before and do they know each other? Will they work

together again? (helps you understand the context and participants)

Have you thought about the social / cultural setting around the meeting you are arranging? (helps

understand the mindset of participants and the external factors that might influence their participation)

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 28

3/9/2016

Is a physical meeting the best way to achieve your objective? (maybe the client hasn't really considered other

ways they could better achieve their desired outcomes)

What support staff and resources do you have? (how much will the facilitator need to bring themselves or

factor in)

Have you asked the participants what they want to get out of the meeting? (maybe there are different

objectives between participants and organiser, or amongst participants, these should come out in the open as

soon as possible)

How much of the client's specifications are flexible? (are there things that can be changed to help the

facilitator)

Who is going to follow up on the work if objectives are not met? (will the facilitator be expected to help with

follow up)

Supporting materials

- Five stages of facilitation preparation:

Module 2 - Can You Facilitate this Course for Us.pdf

This document explains the process you should go through having been asked to facilitate a session - the stages you

should cover as you prepare for that session

- Steps to designing small workshops:

Module 2 - Steps to designing small workshops.pdf

This provides an overview of the logistical preparation for your workshop - a checklist of things to consider to make

sure everything runs smoothly on the day

- Tips for training international groups:

Module 2 - Tips For Training International Groups.pdf

Many groups you facilitate will include participants from all nationalities - here is some advice on how to make sure

everyone contributes and benefits from the session.

- Designing effective workshops - doing things differently:

Different tools to use for different situations

Module 2 - Steps to designing small workshops.pdf

Preparation for next session

Co-facilitators: Pamela and Nils. Rapporteur: please volunteer! We'll contact you soon about a preparation session

together.

If you couldn't make the module, have a look at these notes and if you'd like to discuss anything before the next

module, please email cec@iucn.org .

Facilitation Course: Module 2 Handout

Can You Facilitate This Workshop For Us?

Five Stages for Preparation

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Assessment

Contract

Education

Design

Consultation

1. Assessment

In the assessment stage, you are finding out some key parameters (decisions already

taken), what is the purpose of the event, and then making an assessment of the right kind

of contribution that can be made to helping the “client” achieve his/her goals. This stage

also gives you the information you need to start to draft a design for the workshop. Here

are some key questions:

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 29

3/9/2016

a. Parameters/decisions already taken (Questions to ask the client)

i.

ii.

iii.

iv.

v.

How long is the workshop?

How many people are expected?

When is it?

Where will it be held?

How flexible are the answers to 1-4 above?

b. Purpose (Questions to ask the client)

i. What are your set objectives? (can these be further refined?)

ii. What is your purpose, or other purposes vis-à-vis:

1. Outcomes (changes and impacts you want to see in the

medium term)

2. Outputs (physical products in the short term – decisions,

documents, products, timelines)

3. Feeling of the group at the end of the workshop, or over

time (energized, committed, connected, curious…)

c. Design (Questions to ask the client)

i. What do you have in mind already in terms of a design?

ii. How flexible is your current design?

d. Final Assessment (questions you ask yourself)

i. Do they really need a facilitator? Or something else: trainer,

coach, chairperson, logistics specialist

ii. How much flexibility do I have?

iii. Will I be able to substantively contribute to helping them meet

their goals? YES/NO

iv. Is there the flexibility in the team to change things? YES/NO

v. Is there the time to change things? YES/NO

vi. Is there the support or the buy-in for change? YES/NO

vii. Am I talking to the right person? Is this person a decision-maker?

Do I need to be talking to someone else too? YES/NO

viii. Does the decision-maker trust in facilitation and the process?

YES/NO

2. Contract

This is not a written document, but a conversation that you have with the client that tells

them, based on your assessment, exactly what you can and cannot do for them:

a. What are you realistically able to do under these circumstances, for

example

i. I can help you facilitate your workshop

ii. I can help you design your workshop and brief your team on the

facilitation techniques

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 30

3/9/2016

iii. I can recommend another facilitator

iv. I think a training course would be more appropriate for your

goals, etc.

b. What support do you need, for example

i. For this size of group we will need a second facilitator, or other

people to help

ii. We need a small budget to cover some costs

iii. I need someone who can help with the logistics aspects of this so

that I can concentrate on the dynamics and reaching our goal

c. Is this acceptable to you?

3. Education

a. Is there anything you need to help the client understand before you get

further into the process? Do they need to learn/understand more about:

i.

ii.

iii.

iv.

What facilitators do and don’t do?

How group processes work?

Some of the tools?

The psychology behind facilitated processes?

b. If they do not need any additional information, is there anyone in the process

who does (the decision-maker?)

4. Design

a.

What additional information would you need to develop an interesting design for the

workshop?

i. What kind of workshops have these participants been to before?

ii. What kinds of things do they like to do?

iii. Are there any tools that are overused? Or that other people have suggested

that they try?

iv. What pieces of the agenda do you already have to work with, for example:

1. There needs to be some content input at the beginning and three

panelists have already been lined up.

2. The group needs to go on a site visit to collect some information.

3. There is a lot of high level interest in this workshop so there needs

to be protocol time that allows speeches to be made at some point.

4. There is a lot of disagreement and time needs to be spent

understanding all of the different perspectives of the

problematique, etc.

v. What are some of the logistics parameters that you need to work with:

1. The venue is far away from the hotel, so the days need to start

flexibly in case the buses are late.

2. The hotel can only cater lunch at a certain time.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Page 31

3/9/2016

3. The coffee break area is a walk from the workshop room, so coffee

breaks need to be longer.

vi. How might some cultural considerations provide some insight into your

design vis-a-vis dynamics, logistics, etc?

1. How might the agenda need to take into consideration church

services, or prayer time

2. What is the local custom for lunch times, dinner times?

3. Additional Resource: Training Across Cultures book, or one

chapter “Tips for Training International Groups” (Annex 1)

vii. How might human beings’ physiology inform you about the design?

1. People fall asleep after lunch if they are not active or interested (a

boring speaker, or a slow film will be one way to help people catch

up on their sleep)

2. Variety does a lot to keep people interested, so does surprise

3. Long hours with no breaks, or insubstantial breaks, will not inspire

creativity, etc.

viii. Work with a template and put into place some of the things that are already

agreed or need to happen, and then focus on the purpose of the individual

sessions – how can you best get to where you are going in terms of purpose

and outputs\outcomes?

5. Consultation

Test out your draft design with the client for questions and feedback, even several times if

necessary. At some point, call it finalized and stick to it for documentation purposes (you can

always change things a little during the session to be responsive to participants’ needs.)

Designing Effective Workshops: Doing Things

Differently

Training

Components

Preparation

Room set up

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Traditional

Approach

None –

participants

receive a schedule

and logistics

information

Chairs in theatre

style or classroom

style

Other Options

Prepare a session workbook and send in advance

(people will read it on the plane, train or bus)

Have an email conference with a moderator

Have a live, interactive internet chat on the

session topic.

Provide useful web links for background research.

Give a questionnaire to collect background about

people, their expectations and contributions to

the session – collate and send results prior to the

session (or at least refer to it in the introduction

and your design).

Radial set up with tables

Circle of chairs with tables at the walls

Change the set up occasionally during lunch or

day to day for variation.

Page 32

3/9/2016

Participant

Introductions

Go around the

room and ask

name and

institution.

Plenary discussion

Open the floor

and take questions,

with the speaker

answering them

one by one.

Brainstorming/ideas Plenary

collection

participants shout

out ideas and

facilitator writes

them down

Illustrating points

Give an example

Presentations

1 hour lectures

followed by Q&A

in plenary

Keeping on schedule

Just hope it does

Small group work

Put groups in the

corners of the

room and give

them a time to

work followed by

a report.

In session reporting

and capturing

results of discussion

People stand up

and talk, a staff

member is asked

to take notes and

prepare report of

discussion.

Compiled by Julie Griffin

Images activity

Paired interviews

Opening Circle with a leading question about

expectations of the workshop, etc. can also pass

around something, like a stone to indicate whose

turn it is.

Carousel discussion

Samoan Circle

Buzz groups generating questions

Fishbowl

Carousel discussion

Cards and pinboard

Small group work and reporting

Buzz groups

Use a game (exploratory or confirmation mode), a

video, a case study, a site visit, a stakeholder

discussion

Panel of opposing views followed by breakout

discussions with individual panelists.

Powerpoint presentation with games illustrating

points and audience able to break in with

questions (managed)

Keep it short (15-20 mins) and follow it with

above plenary discussion idea.

Set up workshop norms at the beginning –

discuss expectations for being on time, for

speakers etc. and have people commit to this.

Introduce a timing system for speakers at the

beginning (if at the back of the room use cards for

5 mins (Green card), 1 min (yellow card) and stop

(red card)), or a bell for 1 min and stand up for

stop.

If at the front of the room, stand up at 1 min and

move closer to the speaker as time runs out.

Make the last person in the room in the morning

after the start time sing a song for the group.

Have people pay a small amount for the time they

are late, collect and use to buy a treat for the

group on the last day of the workshop.

Select the groups in a different way each time

(random, draw a number from a hat, on a regional

basis, or assignments)

Give each group a template with questions to

answer on a transparency or flip chart to make the

questions clear, presentations parallel and results

collectable.

Have group select rapporteur and other roles.

Always have the reporter use a visual/job aid,

with questions and answers from the discussion

(e.g.transparency or flip chart) and collect this.

Ask reporter to integrate the salient discussion

points after her/his report and then hand in the

job aid the same day.

Page 33

3/9/2016

Energizers

Stand up and

stretch

Evaluation

Form to fill in

Video the presentations if you might want to use

them again, e.g. as an example for the next

training session.

At the onset of the event ask for rapporteurs for

each discussion and have them send the report at

the end of the session.

Have someone lead the group in a stretch

(different person each time)

Play a game which helps people get to know each

other better: Climb a mountain or An Amazing

Group of people

Go outside to have a discussion

Change the format of the room occasionally, so

people are not always looking in the same

direction at the same wall.

Ask people to sit by someone they don’t know

and sit somewhere different every day.

Closing circle to ask everyone their reflections on

the workshop and what could be improved.

In plenary, two flip charts to record one thing

people learned and one thing to improve.

Mood barometer

Gillian Martin Mehers 27.08.03

Progression of Training

Before

Preparation:

Preparation

at home

(send prep.

documents,