Course: SW 521 – Advanced Anti

advertisement

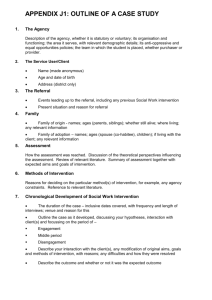

COURSE: SW 521 – ADVANCED ANTI-OPPRESSIVE PRACTICE DISCIPLINE: INSTRUCTOR: SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK ANN CURRY-STEVENS, M.S.W., PH.D. ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF SOCIAL WORK E-MAIL: PHONE: currya@pdx.edu (503) 725-5315 (800) 547-8887 OFFICE HOURS: BY APPOINTMENT I. Course Description This course is a practice course that builds student capacity for anti-oppressive practice in the micro and mezzo practice arenas, with an emphasis on the micro levels of intervention. It centers one particular form of oppression and privilege – that of the positional privilege of social worker and the oppression experiences of service users (clients) and communities that depend on the vitality and responsiveness of our services. While other forms of oppression and privilege will enter the course, and many readings are contextualized on specific forms of oppression, we will engage most fully on the positional privilege of those in the social work profession. Much of AOP encourages a stance of “not knowing” how to practice, so that curiosity, humility and openness to the leadership of communities and service users characterize practice. This course is offered so as to both advance such openness as well as provide some core practices that seek to build the confidence and capacities for students to act in ways that advance equity, social justice and reduce disparities. It is as much about building agency to take action as it is about detailing what such actions incorporate. Integral to the course is the straddling of tensions that are inherent to the field of AOP: knowing and not knowing, acting while continuing to be implicated in relations of domination, and the vulnerability that flows from becoming willing to challenge traditional canons of social work practices. In recognition of this formative and inter-subjective dynamic within AOP, we emphasize that this course is not appropriate for students who simply want to know the “how-to” dimensions of AOP. This course is as much about troubling oneself and one’s practice as it is about figuring out ways to move forward. It will simultaneously involve unraveling what is known and what we thought we knew, as well as working with the humility of figuring out productive avenues for practice. By the end of our course, we will have ideas for effective practice but the field and the nature of the AOP constructs are such that no roadmap for AOP has been written. Specific skills advanced include the ally skills of daily life, conducting micro- and mezzo-level anti-oppressive practice, understanding and responding to the depths of power throughout the engagement and service delivery processes, and becoming more capable of critically self-reflective practice. The course also aims to build an understanding of effective AOP infrastructure for practice. This includes accountability practices at the micro and mezzo levels, and self-accountability, through emphasizing critical self-reflection on the situated dimensions of practice, particularly the positional privilege held in being a professional social worker. The course pedagogy will rely heavily on case study practice. We will use an established set of case studies (selected thematically) and work with these to practice interventions via discussion, role plays and modeling. In 1 this way, the practice dimensions of each week’s materials will be integrated into our classes in an experiential manner. Prequisites of this course are SW 539 and SW 532 or SW 589. II. Learning Objectives At the completion of this course, students will be able to: A. Identify micro and mezzo practices that are congruent with an anti-oppressive analysis. B. Exhibit beginning anti-oppressive practice competencies in the micro and mezzo arena, such as ally skills, AOP counseling skills, critical self-appraisal in the practice context, inviting service user feedback, and assessment of avenues to increase service user power in the organization. C. Understand the requirements for effective anti-oppressive practice. D. Deepen one’s own understanding of self and other, and the complexities of how to use oneself effectively to build effective working partnerships with clients and community members. E. Develop effective partnership practices for partnering with colleagues to deepen one’s own skills and insights and to help colleagues achieve the same. F. Gain practice knowledge about how to reduce the oppressive nature of the social work profession, with concrete ideas for increasing the power of service users in the delivery of services. G. Understand and advance the social justice mandates in the NASW Code of Ethics. III. Required Texts 1. Mandell, D. (2007). Revisiting the use of self: Questioning professional identities. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press. (approx. $35) 2. Course Kit – a course kit is available through the PSU Bookstore. It is a required text for the course. (approx. $50) STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES PSU and the School of Social Work are committed to providing accommodations for students who have disabilities in order to equalize their ability to achieve success in academic classes and to ensure physical access to student activities or university-sponsored events. The Disability Resource Center (DRC) provides academic accommodation for students in both classroom and testing situations and coordinates registration for students with disabilities. The DRC is located in Room 435 Smith Memorial Center and can be reached at 725-4150 and through TTY at 725-6504. Students with disabilities should contact the DRC by the third week of class. A staff member from Disability Resource Center will specify in a letter the accommodations that will be required for this class. The Writing Center in Cramer Hall can provide assistance with writing skills (Room 188F, 503.725.3570, writingcenter@pdx.edu; www.writingcenter.pdx.edu). POPULATIONS AT RISK Social work education programs integrate content on populations-at-risk, examining factors that contribute to and constitute being at risk. Course content (including readings, lectures, class discussions and assignments) educate students to identify how social group membership influences access to resources, and present content on the dynamics of risk factors and responsive and productive strategies to redress them. Populations-at-risk are those who are intentionally or unintentionally discriminated against because of one or more attributes or statuses that fall outside of what is considered normative by dominant social identity groups or are not valued by the dominant society. Social and economic justice content is grounded in the understanding of different models of justice, e.g. distributive justice, human and civil rights, and the global interconnectedness of oppression and privilege. Vulnerable, oppressed and/or marginalized persons and groups are at increased risk of social isolation and economic disadvantage and its consequences because of the pervasive effects of structural inequality and lack of 2 access to power. Diverse population that are vulnerable due to poverty, age, gender, ability, citizenship status, linguistic tradition, nationality, religion, race, and sexual orientation are discussed. Inclusion of content on populations-at-risk directly and explicitly seeks to prepare social workers to practice within the NASW social work code of ethics. ACADEMIC HONESTY AND INTEGRITY All work submitted in this course must be your own, and it must be produced specifically for this course. (If you wish to incorporate some of your prior work into a course assignment, you must have the prior approval of your instructor.) All sources used in your work (ideas, quotes, paraphrases, etc.) must be properly acknowledged and documented. Violations of academic honesty will be taken seriously. Consequences may include failure in the course and suspension from your academic program. It is your responsibility to familiarize yourself with the academic honesty and integrity guidelines found in the current student handbook and online. ACCESS TO INSTRUCTOR Please contact the instructor to set up an appointment. Please use the Blackboard course website to connect with her electronically. INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS This class blends lecture, discussion, films, role-plays, and small group process. EXPECTATIONS FOR ATTENDANCE AND CLASSROOM BEHAVIOR PLEASE TURN CELL PHONES OFF OR TO SILENT RING DURING CLASS. The profession of social work requires a high level of personal integrity and self-awareness. The demonstration of professionalism in classroom behavior, as well as being present and engaged in classroom activities, is expected in this class. Your participation in a respectful learning environment includes: arriving to class on time, coming back from breaks on time, turning off your cell phones, not talking to another student(s) during lecture(s) or when a classmate is speaking, and staying for the entire class. In other words, please be mindful of what might detract from the learning experiences of students and the teacher alike. Course content, class discussions, and assignments for this class rest on an assumption that human diversity is normative. This course and our profession require and expect critical thinking about, and sensitivity to, the impact of diversity (race, class, gender, sexual orientation, religion/faith, culture, ethnicity, physical and cognitive ability, and other considerations), both in relation to the populations we serve, and in the classroom. Students are encouraged to develop and expand their respect for and understanding of diverse identities and experiences. I expect you to be in class and stay for the entire class. I do not make judgments about what is a permissible reason to miss class. Please ask your colleagues for missed notes and/or handouts as you are responsible for course content when you are absent. If you miss a video, that material cannot be borrowed unless it is a video available through PSU’s library. ATTENDANCE If you miss more than three full class sessions, your grade may be lowered by one half letter grade. If this occurs, you must contact the instructor and establish how you will make up the material, if possible. If you miss four full class sessions or the equivalent, you are unlikely to get credit for the course. 3 ASSIGNMENTS & EVALUATION 1. Presentation: Practice digest, role play & student activity (worth 35% of the course grade) DUE: As per assigned date In the first week of class, students will be organized into presentation groups. The task for these groups is three-fold: To summarize the practice that will be illustrated in your presentation. Identify what it is, why it is important, and the ways it can be applied to social work practice. To display a practice that is informed by the assigned case study for the class. You can use video, role play, or other teaching methods to illustrate one or more practices that are indicated in the full set of readings for the class. To then assign to the rest of the students a follow-up activity to be done in small groups that flows from the readings and the role play This participation will be graded by the instructor and each group of students will receive the same grade for this assignment. Please see the grading rubric that will be used for this assignment at the end of this document. Your presentation and activity will occur after the break in each class. All students in the group are required to read all the articles in their assigned week. This is likely to increase your collective wisdom about the role play and activity. If you decide to use a role play, I encourage you to make them as real as possible. Significant learning can flow from role plays – for those who take on roles, they can experience what the encounter feels like and they can evoke deeper insights into practice. For observers, they can be helped to better prepare for practice by seeing examples in action. Maximizing the use of role plays includes developing your own scripts (you may use some but not all of the segments that already exist in the text, and adding/revising sections to integrate the topics of your readings). It also typically involves letting go of these scripts and moving beyond them to find your own words and insights. 2. AOP Portfolio (worth 65% of course grade) DUE: March 11 (in class) Page length – maximum of 8 pages, appendices can be used In this assignment, you are to identify and develop 2 illustrations of your competencies in AOP. The assignment is intended to showcase your best AOP work, ideally that occur through the duration of this course. You must select one mezzo-level intervention and one micro-level intervention. Ideas might include: Social conversations with colleagues, families or friends Advocacy practices at the micro or mezzo level Case recording or client assessment Interview with a client – using a transcript of an interview that either illustrates AOP or that would be redone to illustrate how, now, you might conduct this as an AOP. Organizational assessment of user involvement in service delivery Organizational reform initiative that you intend to undertake Service user testimony of your competencies in AOP Client assessments of your competencies through interviews or surveys Any other AOP practice competency that has been previously approved by the instructor 4 Your task here is to represent this practice and your assessment of your competencies though conventional approaches such as written work, transcripts, or case recordings or less conventional approaches such as videos, drawings, poems, surveys, photographs or audio recordings. Here are the required elements for each of the two practices that you document: 1. Details of the practice 2. Identify forms of AOP in evidence 3. Identify the theoretical and/or conceptual dimensions of the form of AOP, relating these clearly with references to course materials and literatures 4. Assess your competencies in this illustration, noting those that you affirm and those you intend to improve 5. Define your beliefs about the outcomes and impacts of your intervention, with a rationale for these beliefs. Please note that this section is required for your assignment (often overlooked by students). Conclude your paper by reflecting on what you have learned through preparing this review. CUSTOMIZING ASSIGNMENTS Students may request an alternative assignment in two situations: If they find it impossible to complete an assignment due to the limitations of their practicum opportunities or their experience. If students do not find the assignments useful to their practice or their learning. In these situations, students are asked to address the issue with the instructor outside of class time within the first two weeks of class. An adaptation of the assignment is the recommended resolution. If this is not possible, an alternate assignment is to be proposed by the student and approved by the instructor. In this situation, the student will submit a written proposal for the assignment, including the recommended criteria against which the assignment will be graded. The instructor has final authority for approving the proposal and/or modifying it to maximize clarity of expectations and integrity with the overall objectives of the course. FORMAT FOR ALL ASSIGNMENTS Remember to format properly (1” margins, 12-point font, double spaced, Times New Roman font, left justify), reference properly, and to use APA 6th Edition. LATE ASSIGNMENTS Assignments must be handed into the instructor at the start of class on the due date. Extensions can be granted for personal and health reasons. They must, however, be approved the day before the assignment is due in order to avoid a late penalty. Late assignments must arrive to the Faculty of Social Work (at Portland State University) by hard copy, and not electronically. To avoid the “clock” adding penalty to your late deduction, I suggest you discuss with your instructor the possibility of accepting the paper electronically, and then following up with a hard copy. Please note that if your last assignment for the term is late, your instructor will not likely be able to grade it in time for grade submission deadlines. REWRITING ASSIGNMENTS Students who receive a failing grade (C+ or below) for an assignment are permitted to rewrite their assignment. If this grade is obtained in a presentation, students may arrange with the instructor to reformat the presentation to a written assignment for their rewrite. The maximum value for a rewrite is a B+. GRADE APPEALS Students seeking to appeal their grade in a specific assignment are required to do the following: 5 Submit a written request to the instructor detailing the specific ways in which they believe their grade is too low. This written request must include the following: reference to the specific elements of the assignment details and the elements of the grading rubric that are perceived to have been graded too low. The instructor will then respond to the student’s request by revisiting the original assignment and reconsidering the student’s perception of the grade. The instructor may at that time alter the grade and will notify the student of this decision. If the student remains unsatisfied, the instructor will seek the input of another instructor who teaches the same course or a similar course, asking them to read the assignment, the student’s grade appeal, and provide their advice on an appropriate grade for the paper. This grade may be lower than the grade that the original instructor has assigned. The new grade will be the average of the two grades. Class Outline Class 1: Introduction (Jan 7) This class will ensure that all students refresh themselves in the AOP lens, and together we will highlight practice principles unique to AOP. Case Study – Impala station wagon & student scenario (2 case studies used) Class 2: Social work and troubling the “helping” stance of innocence (Jan 14) In this class, we take a critical lens to the ways in which our profession reproduces dominance, and exists as a form of social control, yet simultaneously “hides” much of its substantive impact through an uncomplicated stance of “helping.” We will explore avenues at the discursive level and the structural levels to remove such cloaking, identify avenues to resist such practice and promote alternatives to dominant social work practice. Required Rossiter, A. (2001). Innocence lost and suspicion found: Do we educate for or against social work? Critical Social Work, 2(1) 1-5. McKnight, J. (1995). Professionalism (exerts). In The careless society: community and its counterfeits (pp.16-25 and 36-52). New York: Basic Books. Mclaughlin, K. (2005). From ridicule to institutionalization: Anti-oppression, the state and social work. Critical Social Policy, 25, 283-305. (will be posted online) Recommended Margolin, L. (1997). Introduction. In Under the cover of kindness: The invention of social work (pp. 1-12). Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia. Kivel, P. (2000). Social service or social change? Who benefits from your work? [Download and/or print from www.socialworkgatherings.com/Social%20Services%20or%20Social%20Chang.pdf] Case study – Trent and Trent Revisited Class 3: Being an Ally and Interrupting Oppression (Jan 21) Key beginning steps in AOP is that of ally practice, including interrupting oppression when you see it in action. This class will be both practice-heavy as well as stretching ourselves into wondering about the challenges posed by AOP. Note that despite the number of articles, the number of pages to be read is relatively short. Required Kivel, P. (2003). Being a strong white ally. In M. Kimmel & Ferber, A. (Eds.) Privilege: A reader, pp.401-411. Thompson, A. (2008). Resisting the “lone hero” stance. In M. Pollock (Ed.), Everyday anti-racism: Getting real about race in school (pp.327-333). New York: The New Press. Bonilla-Silva, E. & Embrick, D. (2008). Recognizing the likelihood of reproducing racism. In M. Pollock (Ed.), Everyday anti-racism: Getting real about race in school (pp.334-336). New York: The New Press. 6 Glass, R. (2008). Staying hopeful. In M. Pollock (Ed.), Everyday anti-racism: Getting real about race in school (pp.337-340). New York: The New Press. Peters, M., Castaneda, C., Hopkins, L. & McCants, A. (2010). Recognizing ableist beliefs and practices and taking action as an ally. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, R. Castaneda, H. Hackman, M. Peters, & X. Zuniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp.528-531). New York: Routledge. Spade, D. (2010). Mutilating gender. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, R. Castaneda, H. Hackman, M. Peters, & X. Zuniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp.435-441). New York: Routledge. Recommended Pollock, M. (2008). Complete list of everyday antiracist strategies. In M. Pollock (Ed.), Everyday anti-racism: Getting real about race in school (pp.343-348). New York: The New Press. Sazama, J. (2010). Allies to young people: Tips and guidelines on how to assist young people to organize. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, R. Castaneda, H. Hackman, M. Peters, & X. Zuniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice: An anthology on racism, anti-semitism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism, and classism (pp.578580). New York: Routledge. Case Study – Kivel’s strong white ally Class 4: Understanding Self & Practicing Critical Self Reflection (Jan 28) Understanding the practice context as deeply influenced by the embodied identities of service user and worker leads us to emphasize critical self reflection. Skills emphasized include conscious efforts (lifelong) to understand the “self,” as situated in the unique context. We then will concretely examine the impact of situated practice on the counseling relationship. Required Morley, C. (2008). Teaching critical practice: Resisting structural domination through critical reflection. Social Work Education, 27(4), 407-421. Mandell – Chapter 1 – Use of self: Contexts and dimensions Fook, J. & Gardner, F. (2007). Critical reflection and direct practice. In J. Fook & G. Gardner, Practising critical reflection: A resource handbook (pp.174-187). Maidenhead, England: McGraw (will be posted online) Recommended Wong, R. (2004). Knowing through discomfort: A mindfulness-based critical social work pedagogy. Critical Social Work, 5(1). Jeffrey, D. (2005). What good is anti-racist social work if you can’t master it? Exploring a paradox in anti-racist social work education. Race, ethnicity and Education, 8(4), 409-425. Case study – D’Hondt (in textbook) Class 5: Understanding service users and counseling basics (Feb 4) When we center issues of gender, race, class, sexual orientation and other forms of oppression, we are called upon to respond to these issues in our direct service work with clients. What, then, is counseling to address? To begin, we need to be able to invite this content, to hear these issues, and then to respond appropriately. Our work today begins with understanding the microaggressions that people from marginalized communities experience. Our second objective is to consider what is known about their needs and priorities. The recommended readings address AOP in mandated settings. Required Shragge (Ch.10 in Mandell) – “In and against” the community: Use of self in community organizing Sue, Derald Wing (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. The American Psychologist, 62 (4), 271-286. Mullaly, B. (2002). Anti-oppressive social work practice at the personal and cultural levels. In Challenging oppression: A critical social work approach (pp.170-192). Don Mills, ON: Oxford. 7 Recommended Pollack, S. (2004). Anti-oppressive social work practice with women in prison: Discursive reconstructions and alternative practices. British Journal of Social Work, 34(5), 693-707. Strega, S. (2007). Anti-oppressive practice in child welfare. In D. Baines (Ed.). Doing anti-oppressive practice: Building transformative politicized social work (pp.67-82). Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press International. MacLeod, B. (2013). Social justice at the micro level: Working with clients’ prejudices. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 41(3), 169-184. Case Study – D’Hondt (in textbook) Class 6: Use of Self and Case Records (Feb 11) Counseling practices require considerable attention to the “therapeutic alliance” (in clinical frames) and issues of trust, respect and authenticity (in critical frames). As a result, heightened importance is placed on how the social worker both knows themselves as well as how they both intentionally and unintentionally use their experience and emotional response to the client. In this class, we reflect on the self and how we might position ourselves to advance successful outcomes with clients in both in-the-room engagement and in our assessments and case records. Issues of discourse analysis are a required focus as well. Required Rossiter (Ch.2 in Mandell) – Self as subjectivity: Toward a use of self as respectful relations of recognition Grant (Ch. 4 in Mandell) – Structuring social work use of self Mullaly, B. (2002).Internalized oppression and domination. In Challenging oppression: A critical social work approach (pp.123-145). Don Mills, ON: Oxford. Strega, S. (2006). Anti-oppressive approaches to assessment, risk assessment and file recording. In S. Strega & S. Esquao (Eds), Walking this path together: Anti-racist and anti-oppressive child welfare practice (pp.142157). Black Point, NS: Fernwood. Recommended Dewane, C. (2006). Use of self: A primer revisited. Clinical Social Work Journal, 34(4), 543-558. Pollack (Ch.7 in Mandell) – Hope has two daughters: Critical perspectives within a woman’s prison Morrel (Ch.5 in Mandell) – Power and status contradictions Finch, J., Bacon, J., Klassen, D. & Wrase, B. (1999). Critical issues in field supervision: Empowerment principles and issues of power and control. In W. Shera (Ed.) Emerging perspectives on anti-oppressive practice (pp.431446). Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press International. Case Study – Grant (in textbook) Class 7: Clinical Practice (Feb 18) Taking our counseling practices to a more advanced level, we turn to the forms of intervention that seek to address the roots of how oppression has embedded in the psyche in damaging ways and the options that clinicians have for assisting in transformative work with clients. Experiences of both oppression and privilege influence one’s psyche, with a set of damages and traumas that influence one’s self-concept, one’s resilience, and one’s experiences of expectations for future treatment. Required Kumsa (Ch.6 in Mandell) Rossiter, A. (2000). The professional is political: An interpretation of the problem of the past in solutionfocused therapy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(2), 150-161. Brown, C. (2007). Feminist therapy, violence, problem drinking and re-storying women’s lives: Reconceptualizing anti-oppressive feminist therapy. In D. Baines (Ed.), Doing anti-oppressive practice: Building transformative politicized social work (pp.128-144). Black Point, NS: Fernwood. Sucharov, M. (2013). Politics, race, and class in the analytic space: The healing power of therapeutic advocacy. International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology, 8(1), 29–45. 8 Recommended Kamya, H. (2007). Narrative practice and culture. In E. Aldarondo (Ed), Advancing social justice through clinical practice (pp.207-220). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates Inc. Waldergrave, C. (2005). “Just therapy” with families on low incomes. Child Welfare, 84(2). 265-276. Clark, J. (1999). Reconceptualizing empathy for anti-oppressive, culturally competent practice. In W. Shera (Ed.) Emerging perspectives on anti-oppressive practice (pp.247-264). Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press International. Hernandez, P., Almeida, R. & Dolan-Del Vecchio, K. (2005). Critical consciousness, accountability and empowerment: Key processes for helping families heal. Family Process, 44(1), 105-119. Case Study – Saundra Santiago Class 8: Accountability Practices to Services Users (Feb 25) This class will explore micro dimensions of accountability practices including continued discussion of critical selfreflection, as well as collegial practices of building effective learning dyads (or “critical friendships”), supervision, giving & receiving feedback, and inviting feedback from service users. Required Larson, G. (2008). Anti-oppressive practice in mental health. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 19(1), 3954. Beresford, P. & Croft, S. (2001). Service users’ knowledges and the social construction of social work. Journal of Social Work, 1(3), 295-316. Dumbrill, G. & Lo, W. (2009). What parents say: Service users’ theory and anti-oppressive child welfare practice. In S. Strega & S. Esquao (Eds), Walking this path together: Anti-racist and anti-oppressive child welfare practice (pp.127-141). Black Point, NS: Fernwood. Recommended Strier, R. & Binyamin, S. (2010). Developing anti-oppressive services for the poor: A theoretical and organizational rationale. British Journal of Social Work, 40(6), 1908–1926. (posted online) Swanson, J. (2001). What poor people say about poor-bashing. In Poor-bashing: The politics of exclusion (pp.928). Toronto, ON: Between the Lines. Beresford, P. (2000). Service users’ knowledges and social work theory: Conflict or collaboration? British Journal of Social Work, 30(4), 489-503. Sistering (2007). Anti-Oppression and Diversity Policy. (posted online Hair, H. & O’Donoqhue, K. (2009). Culturally relevant, socially just social work supervision: Becoming visible through a social constructionist lens. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 18(1-2), 70-88. Case Study – Saundra Santiago Class 9: Organizational Equity and Strategically Advancing Reforms (March 4) At the mezzo level, institutions replicate and entrench relations of domination. We will briefly explore the ways in which institutions enact oppression and then identify avenues for remedying such dynamics. Required Sue, D. (2010). Microaggressive impact in the workplace and employment. In Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender and sexual orientation (pp.209-230). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. NASW (2007). Institutional racism and the social work profession: A call to action. Washington, DC: NASW. [Download and/or print on your own from http://www.socialworkers.org/diversity/InstitutionalRacism.pdf] Curry-Stevens, A. (2007). New forms of transformative education: Pedagogy for the privileged. Journal of Transformative Education, 5(1), 33-58. Curry-Stevens, A. (2013). In defense of culturally-specific services: An epistemological, ideological and outcomes-based appeal. [under review with Advances in Applied Sociology]. Recommended 9 Swanson, J. (2001). To equalize power among us. In Poor-bashing: The politics of exclusion (pp.195-196). Toronto, ON. Between the Lines. Curry-Stevens, A., Cross-Hemmer, A. & Coalition of Communities of Color (2010). Communities of Color in Multnomah County: An unsettling profile. Portland, OR: Portland State University. [Download and/or print on your own from www.coalitioncommunitiescolor.org] Curry-Stevens, A. (2011). Persuasion: Infusing advocacy practice with insights from anti-oppression practice. Journal of Social Work, 12(4), 345-363. Case study –Maiter Class 10: Managing Tough Conversations around Equity (March 11) AOP PORTFOLIO DUE With gratitude to Cliff Jones, Senior Consultant, Nonprofit Association of Oregon, we are replicating much of Cliff’s workshop on this topic. Students are frequently requesting concrete methods for successfully navigating difficult conversations about equity that arise in their classrooms, workplaces and their own families. This class will be established as a “flipped classroom” and students will review online content in lieu of much reading (except a small selection below). Come to class prepared to engage in conversations, with case scenarios used for our work. Required Readings Sue, D., Lin, A., Torino, G., Capodilupo, C. and Rivera, D. (2009). Racial Microaggressions and Difficult Dialogues on Race in the Classroom. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(2), 183-190. Singleton, G. & Linton, C. (2006). The fourth condition: Keeping us all at the table. In Courageous conversations about race: A field guide for achieving equity in schools (pp.117-155). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Johnson, N. (2013). A poem for my white friends: I didn’t tell you. Understanding and Dismantling Privilege, 3(1), 1-3. Case Study – still to be determined 10 Grading Rubrics for Two Assignments This first rubric will be applied for the group presentation assignment. 11 The following rubric will be used for grading the AOP portfolio assignment. Note that each of the two required practice illustrations will be allocated the same grade weighting. A portion of the grade is allocated to writing style and use of APA. Approximately 10% of the assignment grade is determined by the score on writing style and use of APA. 12