biological risk factors - Dartmouth

advertisement

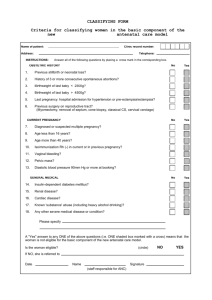

DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 1 Risky Sex and Risks of Teen-Age Pregnancy Art Maerlender, Ph.D. & Kathy Kovner-Kline, M.D., M. Div. Human reproduction can be seen as a significant stage in the cycle of human sexuality. From birth to adulthood, stages of development reflecting different levels of meaning and expression have been identified. Besides the physical aspects of sexuality, there are complex cognitive and social-emotional developmental processes including capacity for intimacy, affiliation, communication, mutual respect and responsibility. A variety of risks may affect sexuality development at any stage and facet of it, including the timing and situation of pregnancy (Haka-Ikse, K., 19971). Adolescent pregnancy is seen as an inappropriate expression of sexuality in modern American culture. It has been identified as one of the Dept. of Justice’s (DOJ) serious psychosocial maladjustment problems. Adolescence is usually too young an age to become a parent in the contemporary United States. This is largely because raising a child takes patience and resources that are acquired in advanced societies gradually with age, education, and experience. Moreover, among adolescents, it is those who are least well prepared to nurture and raise a child who are most likely to become parents. That is, adolescents who have substance abuse and behavior problems, who are not doing well in school, who have low aspirations for their own educational attainment, and who live in economically disadvantaged families and communities tend to start sexual intercourse at younger ages. For those, contraception is less effective, and they have unintended DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 2 pregnancies (Moore, ?2). Sexually active teenagers are also at increased risk for contracting sexually transmitted diseases (STD) such as HIV. This review considers data and research regarding the risks of adolescent (teenaged) pregnancy in the United States. Teenage pregnancy includes not only those who have live births, but those who become pregnant and lose their children through miscarriage or abortion. The studies reviewed include girls who are married and unmarried, as well as those who have second or more births while under the age of 20. Some research also has looked at the role of male behavior and attitudes in teen pregnancy. Engaging in sexual intercourse is, of course, one risk factor for pregnancy. However, with current birth control methods, sexual behavior need not be a predictor of pregnancy. Yet early sexual activity is a clear risk factor for later pregnancy, and as such is one rather obvious area of study (i.e., who are the people more likely to engage in early sexual activity), although it, by itself, is not the only risk factor studied. Risk factors for teen pregnancy are, like other psychosocial maladjustment problems, are multi-factorial. Although there is good news regarding the incidence of teen pregnancy, the factors that put children at risk continue to be problematic and point to socio-cultural and well as biopsychological factors that continue to plague society. Haka-Ikse, K. (1997). “Female adolescent sexuality. The risks and management.” Ann N Y Acad Sci 816: 466-70. 1 2 BEGINNING TOO SOON: ADOLESCENT SEXUAL BEHAVIOR, PREGNANCY AND PARENTHOOD A REVIEW OF RESEARCH AND INTERVENTIONS by Kristin A. Moore, Brent C. Miller, Barbara W. Sugland, Donna Ruane Morrison, Dana A. Glei, Connie Blumenthal, DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 3 Trends throughout the 1990s have shown a steady reduction in teen birth rates that are now significant for all 50 states. Rates have declined for all adolescent age groups, for all racial and ethnic groups, and for both first and second births to teens. Throughout the 1990s, black teens have had the largest declines in teen childbearing rates of any group. However, U.S. teen pregnancy rates remain among the highest in the industrialized world, and birth rates for Hispanic and black teens continue to be substantially higher than those for non-Hispanic white and Asian or Pacific Island youth (HHS, 2000). Birth rates for teenagers 15-19 years generally declined in the United States since the late 1950s, except for a brief, but steep, upward climb in the late 1980s until 1991 (Ventura & Mathews, 2001). The youngest group, aged 10-14, showed the lowest birth rates since 1967. The latter decline occurred despite the fact that the population of girls in this age group actually increased during this time period (HHS, 2000). Overall the range of decline in State rates for ages 15-19 years was 11 to 36 percent. Analysis of National census and demographic data indicated that the factors accounting for these declines included decreased sexual activity. The decline was felt to reflect several factors: changing attitudes towards premarital sex, increases in condom use, and adoption of newly available hormonal contraception, implants, and injectables (Ventura & Mathews, 2001). DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 4 In reviewing the causes of the explosion in teen birthrates in the 1980’s, Manlove et al (2000) identified specific factors associated with this increase, including negative changes in family environments (such as increases in family disruption) and an increase in the proportion of teenagers having sex at an early age. These authors used data from the 1995 cycle of the National Survey of Family Growth to compare the experiences of three cohorts of teenage females in the 1980s and 1990s. Based on this analysis, they identified several factors associated with the recent decline in the teenage birthrate. These included positive changes in family environments (such as improvements in maternal education), formal sex education programs and discussions with parents about sex, stabilization in the proportion of teenagers having sex at an early age and improved contraceptive use at first sex. However, even with these improving statistics, almost one million adolescents become pregnant each year ( 19 percent of those who have had sexual intercourse)3. Among women aged 15 to 19, 78 percent of pregnancies are believed to be unintended4.. Another disturbing trend is that in the mid- 1990s age of first intercourse was happening younger than in the 1980s thus expanding the age-range and increasing the risks of becoming pregnant while a teenager (Manlove et al, 2000). Eisen et al (2000) analyzed the YRBS data and found that those who engaged in any “risk behaviors” tended to take part in more than one risky behavior, and that many 3 4 Ventura, 2001, Henshaw, 2000. Henshaw SK, Unintended pregnancy in the United States, FamilyPlanning Perspectives , 1998, vol. 30. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 5 health risk behaviors occurred in combination with other risky activities5. Other studies have found that prior substance use increases the probability that an adolescent will initiate sexual activity, and sexually experienced adolescents are more likely to initiate substance use – including alcohol and cigarettes (Mott & Haurin, 1988; this finding was replicated in Lammers, 2000)6. The 1997 YRBS data confirmed that teens who use alcohol or drugs are more likely to have sex than those who do not: Adolescents who drink are seven times more likely, while those who use illicit substances are five times more likely – even after adjusting for age, race, gender, and parental educational level (CASA, 1999). Thus, engaging in many types of risky behavior often includes sexual activity that can lead to pregnancy and unintended fatherhood. Drugs and Sex In this regard, the role of substance use and sexual activity is of particular concern. Sexual activity and substance use are common among youth today. These are behaviors that are far more acceptable in adults, but appropriately unacceptable in teenagers. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 79 percent of high-school students report having experimented with alcohol at least once, and a quarter report frequent drug use7. As noted above, half of all 9th -12th graders have had sexual intercourse, and 65 percent will by the time they graduate. While it has been difficult to 5 4 Eisen M et al., Teen Risk-Taking: Promising Prevention Programs andApproaches, Washington DC: Urban Institute, September 2000. (YRBS data) 6 5 Mott FL and Haurin RJ, Linkages between sexual activity and alcohol and drug use among American adolescents, Family Planning Perspectives, 1988, vol. 20. 7 CASA: The National Center of Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, (1999). Dangerous liaisons: Substance abuse and sex. New York, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 6 show a direct causal relationship, there is some evidence that alcohol and drug use by young people is associated with risky sexual activity8. Results from a Kaiser Family Foundation survey, together with other recent research, paints a troubling picture of the relationship between alcohol use, sexual activity and unintended pregnancies among adolescents. One-quarter of sexually active 9-12 th grade students report using alcohol or drugs during their last sexual encounter, with males (31%) more likely than females (19%) to have done so (Centers for Disease Control, 2000). Up to 18 percent of young people aged 13 to 19 report that they were drinking at the time of first intercourse, and among teens aged 14 to 18 who reported having used alcohol before age fourteen, 20 percent said they had sex at age fourteen or earlier (compared with seven percent of other teens: CASA, 1999). The use of condoms has been proposed as an important preventative method for the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases and an effective contraceptive method for those who choose to engage in premarital sexual intercourse. Use of condoms is a factor in the link between sexual activity and drug abuse. The more substances that sexually active teens and young adults have ever tried, the less likely they are to have used a condom the last time they had sex: Among those aged 14 to 22, 78 percent of boys and 67 percent of girls who reported never using a substance said that they used a condom, compared with only 35 percent of boys and 23 percent of girls who reported The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 1999, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, June 2000, vol. 49. 8 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 7 ever having used five substances9. Teen girls and young women aged 14 to 22 who have recently used multiple substances are less likely to have used a condom the last time they had sex: 26 percent of young women with four recent alcohol or drug use behaviors reported using a condom at last intercourse, compared with 44 percent of those who reported no recent alcohol or drug use. By their own report, fifty percent of adolescents surveyed acknowledge that having sex while drinking or on drugs is often a reason for unplanned teen pregnancies10 (CASA, 1999, KFF, 1996).1,15 Thus, youth who engage in sex while using drugs are less likely to use condoms and are at greater risk of unintended pregnancy. Of course, this makes perfect sense as the effects of drugs interfere in rational thought processes, or controlled behavior. BIOLOGICAL RISK FACTORS In a review of the research on teen pregnancy, Miller at al (2001) noted several biological factors that were related to adolescent pregnancy risk, notably timing of pubertal development, hormone levels, and genes. These factors were relevant because of their association with adolescent sexual intercourse. Early puberty, looking older, etc., are likely genetically linked, but the consequences are manifest within later psycho-social contexts. These physical traits has been associated with other psycho-social maladjustment problems that in themselves 9 11 Santelli JS et al., Timing of alcohol and other drug use and sexual risk behaviors among unmarried adolescents and young adults, Family Planning Perspectives, 2001, vol. 33. 10 15 Kaiser Family Foundation, 1996 KFF Survey on Teens and Sex: What they say teens today need to know and who they listen to: Chart Pack, Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, 1996. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 8 increase the risks of pregnancy (see Orr, 199111), such as self-esteem (Anderson et al, 1989) depression (Angold et al, 1992) and delinquency (Silberstien et al 1989). In addition, early puberty is probably less a risk factor in an optimal family-social environment (Miller, 2001). Thus, early physical maturation impacts development in ways that put the child at risk later in life, so they are not as notable early on. PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS Sexual Behaviors In 1997, Resnick noted a sharp increase in sexual behavior between 7th-8th graders and 9th-12th graders. Approximately 17% of 7th and 8th graders and nearly half (49.3%) of 9th through 12th graders indicated that they had ever had sexual intercourse. Further, among sexually experienced females aged 15 years and older, 19.8% reported having ever been pregnant. A history of pregnancy was associated with length of time since age of sexual debut, thus, the earlier the onset of sexual behavior, the greater the risk of becoming pregnant by the end of high school (Manlove et al, 2001; Resnick, 1997). Protective factors included perceived (negative) consequences of becoming pregnant and use of effective contraception at first and/or most recent intercourse (Resnick, 1997). Of concern is the increasingly sexualized behavior of younger and younger students. While no studies have yet been published, a number of 3rd and 4th grade DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 9 teachers have reported to the first author of their concern about the sexual talk and actions of students in their classrooms. Inappropriate language and grabbing behaviors are reportedly on the rise. Descriptions of adult sexual activity is frequent. Cognitive Status Intelligence has generally been shown to be inversely related to problem behaviors. A very few studies have looked at the role of intelligence and the initiation of sexual activity. Unfortunately, potential sampling biases have made many of them susceptible to criticism of inflated relationships. Halpern (2000) reports on only two studies that suggested a relationship between early sexual activity and intellectual functioning, both demonstrating the same inverse relationship12. Halpern et al (200013) analyzed data from two large samples (National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health and The Biosocial Factors in Adolescent Development), looking specifically at the relationship of a general measure of verbalintellectual function and the timing of first intercourse. They found distinct differences in results for early adolescents (those younger than 15 years old) and older adolescents. For 11 See endote file 052502 for these 4 refs. PLEASE GET Angold and Silberstein 12 R.L. Cliquet and J. Balcaen, Intelligence, family planning and family formation. In: R.L. Cliquet, G. Dooghe, D.J. Van de Kaa and H.G. Moors, Editors, Population and Family in the Low Countries. III, Netherlands Interuniversity Demographic Institute, Voorburg (1983), pp. 27¯70; Mott FL. Early fertility behavior among American youth: Evidence from the 1982 National Longitudinal Surveys of Labor Force Behavior of Youth. Paper presented at the America Public Health Association meetings, Dallas, November 1983. 13 Halpern, Carolyn T., Kara Joyner, Richard J. Udry, and C. Suchindran. 2000. “Smart Teens Don’t Have Sex (or Kiss Much Either).” Journal of Adolescent Health 26 (3): I have this. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 10 the older adolescents, both lower and higher scores on the test appeared to be protective of sex initiation, while more middle, or average scores were a risk factor. After controlling for age, pubertal development, and mother's education, adolescents who were at the upper and lower ends of the test score distribution (i.e., ±1 standard deviation or more) were less likely to have had sex. Racial differences were not significant, but the relationship did vary by age. Among early adolescents (<15 years old), the relationship is primarily linear and inverse; that is, lower test scores indicate a greater likelihood of having intercourse, while higher test scores indicate a lower probability. The data also indicated that even pre-coital behaviors, such as holding hands and kissing, were inversely related to test scores. The authors noted that this finding suggested that higher intelligence was associated with a generalized delay in the onset of all partnered sexual activities (Halpern, et al, 2000). Halpern et al comment that the range of scores reflecting greatest risk was between an IQ equivalence of 75 and 90 (2000). This is the same range noted for higher risks for may problem behaviors. They note that scores in this range are likely reflective of other processes. Adolescents with higher intelligences do demonstrate stronger commitments to conventional attitudes and institutions (see Social factors, below). These values serve to help postpone sexual activity (though they have no relationship to sexual interest). On the other end of the spectrum, those with the lower scores appear to be protected by fewer opportunities as well as adult “gatekeepers” who exert protective influence. 213–25. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 11 Attitudes and beliefs A variety of different personal attitudes and beliefs are associated with risks for teen pregnancy. In Lammers’ study (2000), high levels of body pride were associated with higher levels of sexual activity for all age and gender groups. In addition to the links between drugs and sexual behavior in adolescents, there is also a link between attitudes towards violence. Steuve, et al (2001) found that positive attitudes towards early initiation into sex for both girls and boys was related to violence. These individuals also held positive attitudes to a wide range of conduct problems, including violence, and substance abuse. This is supported by other studies that show that aggressive females are at greater risk for teen pregnancy. There is some growing evidence that fear of contracting sexually transmitted diseases (STD) is protective against early intercourse and early pregnancy (see Kirby, 200114). Thus, it would seem that those without the knowledge or fear of STD’s might be at greater risk. In support of an education as protective argument, several studies have shown that comprehensive sex education classes are responsible for delays in first intercourse experiences, while abstinence-only education has not been shown to be effective. Bearman and Bruckner (200115) studied the outcome of a substantial faithbased movement within the Baptist Church. A movement to take “virginity pledges” was initiated in 1993 with over 2.5 million youth vowing to maintain virginity until marriage. This movement gained considerable publicity because of its acknowledged success in 14 Kirby, D. (1997). No easy answers: Research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy. March, 1997. Wash. DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen pregnancy. Online. www.teenpregnancy.org/fmnoeasy.htm. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 12 reducing the rate of teen pregnancy within that population. The results of the movement and the study were over-interpreted (see Risman and Schwartz (200216). Both Risman and Schwartz, and Bearman, and Bruckner in the original article, point out that the effectiveness of abstinence pledges was related to a group membership phenomena and thus highly restricted in its effectiveness. Age effects were noted, as well as a group phenomenon. It appeared that the pledges only served as protective within ‘groups’ of a particular size. That is, when adolescents pledged as part of a small group activity, it was effective. When that group became too large, or too small, it was not as effective. Violence and Aggression As noted above, patterns of childhood aggression are related to adolescent pregnancy. Miller-Johnson replicated an earlier study that demonstrated (i.e., M. K. Underwood et al, 1996) that girls who were aggressive as children (3rd-5th grade) were more likely to become mothers as teenagers. In addition, girls who displayed stable patterns of childhood aggression were at a significantly higher risk not only to have children as teenagers, but to have more children and to have children at younger ages (Miller-Johnson, 1999). There is growing evidence that girls who have been victimized by physical and emotional maltreatment are more likely to engage in earlier sexual activity and are less likely to use contraceptives. 15 Beerman and Bruckner (2001). Promising the future: Virginity pledges and first intercourse. Am J of sociology, 62, 999-1017. 16 Risman and Schwartz (2002)After the sexual revoultion: gender politics in teen dating. Contexts, vol?, 16-24. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 13 In a longitudinal study of the effects of early childhood maltreatment, 56 female and 36 male adolescents who had become parents while under 20 yrs of age were compared with 117 female and 180 male adolescents who had not become parents during their teenage years (Herenkohl, et al 199817). A range of risk factors were explored that included experiences of sexual and physical abuse. Children were assessed at preschool age in the mid-1970's, at elementary school age, and again during late adolescence and early adulthood in the early 1990's. Results showed that preschool and school-age physical abuse alone and in combination with parental neglect were found to have significant relationships with teenage parenthood. Low self-esteem, as evaluated by elementary school teachers, was related to both early maltreatment and teenage parenthood. Sexual abuse, based on retrospective reports of the adolescents, had a significant but weaker relationship to teenage parenthood. Adams and East (1999) also found that a history of physical abuse, but not sexual abuse, was strongly associated with adolescent pregnancy. Their sample was quite small (100 females between the ages of 12 and 24) and analyses were only correlational. However, the trend of past abuse serving as a risk for later pregnancy was generally supported. In a study of over 1,000 African American females, Fiscella et al, (1998) found that sexual abuse during childhood, but not physical or emotional abuse, was related to earlier age of onset of sexual behavior and earlier age of first pregnancy. These Herrenkohl, E. C., R. C. Herrenkohl, et al. (1998). “The relationship between early maltreatment and teenage parenthood.” Journal of Adolescence 21(3): 291303. 17 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 14 relationships held even after controlling for household income, parental separation, urban residence, age of menarche, and teen smoking. Stock et al (1997) analyzed data on over 3,000 girls in Washington State to analyze the association of a self-reported history of sexual abuse with teenage pregnancy and with sexual behavior that increases the risk of adolescent pregnancy. Those with a history of sexual abuse were more likely to report having had intercourse by age 15. In addition, respondents who had been sexually abused were 3.1 times as likely to say they had been pregnant, compared to those who had not been abused. Raj et al (2000) analyzed data from the 1997 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that both adolescent girls and boys with a histories of sexual abuse reported greater sexual risk-taking than those without such a histories. The incidence of partner violence has also begun to show up a risk for pregnancy. Silverman recently studied survey data and found that that physical and sexual dating violence against adolescent girls was associated with increased risk of pregnancy, as well as other problem behaviors (2001). Furthermore, the experience of any form of physical or sexual violence was associated with rapid, repeat pregnancies (RRP) within 12 months, in a small sample of low-income adolescents Jacoby et al, 1999). Personal Religiosity Lammers et al (2001) replicated past studies and found that strong religious feelings helped to delay the onset of sexual activity for both males and females, and thus served as a protective factor. Past studies have suggested that this effect was stronger for DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 15 males than females (Mott, 199618). Gender differences were not found in a study of late adolescent college students that examined sexual activity, type of religiosity and condom use (Zaleski and Schiaffino, 2000). Groups of 1st-year college students completed surveys about extent of sexual activity and religious orientation. Religious orientation was based on the Religious Orientation Scale (Allport and Ross, 1967). which views religiosity in terms of intrinsic or extrinsic19 purposes for the individual. Zaleski and Schiaffino’s findings demonstrated that sexually active students scored lower on both religiosity scales, leading the authors to interpret religiosity as protective of sexual activity. One caveat was noted that in the subgroup of sexually active students who scored high on religiosity, there was a lower use of condoms. So while religiosity was protective against sexual activity, for those who were religious and engaged in sex, the religiosity of the subjects in this sample appeared to be a risk factor for unsafe sexual practice. Psychological Distress Psychological distress (e.g., symptoms of anxiety, depression, stress) is a risk factor by virtue of its influence on perceptions, attitudes and behaviors. For example, everyone is more prone to poor decision making, impulsive actions and short-tempers when under stress; adolescents are no different. In fact, the developmental nature of adolescent self-regulatory functions suggests that they are more prone to these 18 Mott et al, 1996. Determinants of first sex by age 14 in a high risk adolescent population. Fam. Plan perspectives, 28, 13-18. 19 . Extrinsic orientation refers to use of religious for solace, security, self-justification or status. According to Allport and Ross, these are “outside ends.” On the other hand, intrinsic orientation is associated with church attendance and a view that religion shapes everyday activity; it suggests that the individual has a master motive that shapes their participation. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 16 disruptions in functioning. In a study of behaviors associated with risks of contracting HIV and sexually transmitted diseases in a sample of 522 African American girls aged 14 to 18, levels of distress were assessed at the beginning of the study and 6 months later. Psychological distress influenced the girls’ perceptions about sexual relationships, such as barriers to condom use, less perceived control in the relationship, and being more fearful of the adverse consequences of negotiating condom use (DiClemente, 200220). Girls with high scores on the ‘psychological distress’ measures were more likely to engage in risky behaviors - and twice as likely to get pregnant - than the non-distressed girls during that 6-month time period on the study. In addition, the distressed girls were one-and-a half times as likely to not use any form of contraception. The researchers suggested that this might be because distressed girls lose the confidence to negotiate safe sex practices with their partners. Relatedly, in a sample of 308 lower income, African-American females, MillerJohnson found that females who were depressed in mid-adolescence were at greater risk to become parents from 15-19 yrs. of age (1999). Lammers also found that 13-14 year old females with fewer symptoms of depression were less likely to have initiated sexual intercourse (2000). Clearly, depressed mood, problem solving and decision making have historically been linked. Poor decision making regarding sexual behavior is a logical consequence (also see Harvey, et al, 199521). School-related Variables and Activities 20 Pediatrics online 2001;108:e85 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 17 Several studies have shown a relationship between school performance and pregnancy. Moore analyzed a nationally representative sample consisting of 8,349 females to examine individual, family and school-level predictors of non-marital motherhood between 8th-12th grade. Low individual educational performance measures, such as lower test scores and self reported grades, predicted a higher risk of early motherhood (Moore, 1998). Maynard found that female adolescents who have low school performance and low educational aspirations were more likely to become teenage mothers (199522). Several studies have documented the relationship of parenting practices to educational performance, providing an indirect link between parenting styles and teen pregnancy (Choa, 2001, Dornbusch et al 1987, Rosenthal & Feldman, 1991). Authoritative parenting is more protective, while authoritarian and indifferent styles are related to risk factors. Parents who are interested in their child’s performance at school, who help with homework, etc., increase performance and thus decrease pregnancy risk. As noted above, good school performance was seen as a protective factor against early sexual activity in the Lammers’ et al study (2000). Resnick (1997) identified school connectedness as a critical protective factor against teen pregnancy. Together with positive parental relationships, he suggested that these this could be the most powerful construct or factor for explaining pregnancy risk. In support of this contention, Manlove (199823) analyzed data from a longitudinal cohort of 8th graders and found that factors relevant to teens’ school experiences were related to 21 Harvey, Cet al (1995). Factors associated with sexual behavior among adolescents. Adolescents, 30, 253-264. 22 In Levine, 1998, Am Psych. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 18 pregnancy risk. How supportive the teachers and adminstrators felt, opportunities to be successful, student family background, and individual engagement in school were all associated with the risk of school-age pregnancy leading to a live birth. These factors cut across ethnic groups (white, black, and Hispanic). Among all racial and ethnic groups, high levels of school engagement was associated with postponing pregnancy. Among white and Hispanic teens, dropouts -- especially young dropouts -- were more likely to have a school-age pregnancy. Although the relationship between dropping out and the risk of pregnancy for African-American teens was significant, other measures of engagement were important predictors of having a school-age pregnancy for this group. That is, the degree to which African-American teens felt they were an integral part of the school (either through participation or being respected and valued) was generally more important in predicting pregnancy. Resnick Time-use patterns of 10th graders were also predictive of whether they would engage in a variety of risky behaviors (Zill, 1995). For example, compared to those who reported spending 1-4 hours per week in extracurricular activities, students who reported spending no time in school-sponsored activities were 37 percent more likely to have become teen parents. This and other significant negative relationships were found after controlling for related family, school, and student characteristics such as parent education and income levels, parent involvement in school-related activities, and students' grades. The relationship was direct up to a about 20 hours of extracurricular activity a week. 23 Manlove, J..(1998). The Influence of High School Dropout and School Disengagement on the Risk of School-Age Pregnancy. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8 (2), 187-220. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 19 Teen fathers Less is known about teen fathers than teen mothers. Recent studies have found that teenage fatherhood is associated with problem behaviors such as trouble in school, delinquency, and substance use. In a small sample taken from a larger project in Minnesota, Resnick et al (199324) found that males who caused a pregnancy or those who were unsure whether they had caused a pregnancy were more likely to manifest health compromising and acting-out behaviors than were those with no pregnancy involvement. Pregnancy-involved males were also significantly more likely to believe that causing a pregnancy was a sign of manhood. In a study of males in Pittsburgh, teenage fathers, compared to non-fathers, were significantly more likely to be gang members, to engage in violence, and to have been arrested. Early sexual activity is typically more prominent in males than females. Among African-American males who were more likely to become involved in a pregnancy, there was a higher incidence of antisocial personality characteristics as well as a higher incidence of parental psychopathology (specifically, anxiety and depression). These males initiated sex even earlier than males not involved in pregnancies (Wei, 200025). An analysis of sociological data regarding reductions in teen pregnancy identified an interesting pattern reflecting changes in male-female relationships and the dynamics of Resnick, M. D., S. A. Chambliss, et al. (1993). “Health and risk behaviors of urban adolescent males involved in pregnancy.” Families in Society 74(6): 366-374. 24 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 20 sexual behavior. Risman and Schwartz (2002) suggest that the recent reduction in teen pregnancies is in part due to changes in attitudes of adolescent girls. They note that female sexual activity has not declined as dramatically as has male activity. Within this context, findings of sexual activity occurring in the context of a girlfriend-boyfriend relationship is seen as a mild protective factor, although the exact reasons the increased interest in protecting themselves from negative unintended consequences of sexual activity are not clear “Our best guess is it is related to the increasing power of girls in their sexual encounters” (p. 21), and a change to more relational and less casual sex. SOCIAL Family Context Two parent households provide obvious benefits for supervision and instruction. While the role of extended family constellations has not been studied, two-parent households consistently show up as protective of many problems, while single parent households pose risks. In regards to teen pregnancy, there has been considerable research to demonstrate that teens living in single-parent families, or with stepparents, initiate sexual activity earlier than those in two-parent families (AGI 1994; Hayes 1987; Harris 1996; Miller 199826). There is also evidence that having a sibling within the household who is also a parent increases the risks of adolescent pregnancy for the younger sister. Relative to Wei, E. H.-L. (2000). “Teenage fatherhood and pregnancy involvement among urban, adolescent males: Risk factors and consequences.” Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering 61(1-B): 221. 25 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 21 other youths, the sisters of parenting teens had the highest pregnancy rate 1.5 years after the initial data collection (average age at that time was 15 years old). The authors noted that the increase in time spent caring for the older sister’s child was related to permissive sexual behavior, as well as other negative behaviors (East and Jacobson, 2001). Family Relationships and Factors Parental attitudes and behaviors influence the behavior and attitudes of children. Thornton has summarized the nature and effect of attitudes and values on out-of-wedlock parenting (1995). While the attitudes of the current generation have been shown to be generally less restrictive than those of the last, a comparison across families revealed that children’s attitudes toward a range of family and personal matters (i.e., divorce, gender roles, family size, and premarital sex) tended to reflect the attitudes and values of their parents (Thornton 1992; Axinn et al. 1994; Axinn and Thornton, forthcoming). How well parental attitudes are transferred depends upon the quality of relationships and communications between parents and children. Parents with positive relationships with their children seem to be more effective in the intergenerational transmission of values (Weinstein and Thornton 1989; Moore et al. 1986). Manlove et al (2000) identified several family characteristics that increased the risk of first teenage birth. Ethnicity was consistently related to early pregnancy. Generally, Blacks were at greater risks than whites, as were US-born Hispanics (but not foreign born Hispanic adolescents). Daughters of teenage mothers were also at higher risk. Higher maternal education and greater church attendance lowered the risk. 26 See Beerman and Bruckner for refs) DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 22 Manlove (2000) found that dual-parent families reduced the risk of teen pregnancy, and previous research has indicated that single-parent households increase the risk (Maynard, 1995). Sieving et al hypothesized that adolescent who experience maternal disapproval of sexual activity will start intercourse later (2000). Maternal disapproval was effective for delaying the onset of sexual behavior (and thus lowering risk of pregnancy) if there were feelings of closeness and warmth between mother and daughter. This study found that mother-child discussions bout sex and birth control were not related to early onset, but that the perception of disapproval was critical. To better understand risk factors associated with early onset of sexual intercourse among adolescents, Lammers et al (2000) hypothesized that protective factors identified for other health compromising behaviors would also be protective against the early onset of sexual intercourse. They studied 26,000 students in grades 7-12 (87.5% white, 52.5% male) who did not report a history of sexual abuse in a statewide survey of adolescent health in 1988. High general parental expectations were a significant protective factor for males but not for females. Family connectedness was also a potent factor, particularly for younger adolescents. Parenting Style DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 23 Miller (200127) summarized 2 decades of research about family, and especially parental, influences on the risk of adolescents becoming pregnant or causing a pregnancy. Research findings are most consistent that parent/child closeness or connectedness, parental supervision or regulation of children's activities, and parents' values against teen intercourse (or unprotected intercourse) decrease the risk of adolescent pregnancy. Residing in disorganized/dangerous neighborhoods and in a lower SES family, living with a single parent, having older sexually active siblings or pregnant/parenting teenage sisters, and being a victim of sexual abuse all place teens at elevated risk of adolescent pregnancy. In a re-analysis of their longitudinal data from a study of the children of pregnant teenagers in Baltimore (Furstenburg, et al, 1987; see Furstenburg, 1995), Furstenburg attempted to assess the impact of social capital on several outcomes, including avoidance of having a live birth before age 19. Parenting styles and family organization were assessed for these girls during adolescence. Family-related social capital measures included the extent of extended family support and exchange, presence of a father, and parental investment in their children (e.g., helping with homework, going to school meetings and knowing friends by name). Somewhat surprisingly, social capital appeared unrelated to early pregnancy in their results (although it was strongly related to socioeconomic outcomes). It should be noted that this study was not designed to assess teen pregnancy per se, thus the data analysis was made after the fact, which could have accounted for these negative results. Miller, B. C., B. Benson, et al. (2001). “Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis.” Developmental Review 21(1): 1-38. 27 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 24 In support of this, Resnick’s (1997) review noted that a greater number of shared activities with parents and perceived parental disapproval of adolescent contraceptive use were protective factors against a history of pregnancy. Being a latch-key child was also a risk. Perkins et al (199828) found that (among other factors) children who are home alone for more than 5 hours are at greater risk, with no difference noted among the ethnic groups studied (white, African American, Hispanic). Parental disapproval of sexual intercourse in general has been found to be important. Lammers et al (2000), found that parental support is clearly associated with lower risks for sexual activity (and thus potential pregnancy). They identified social factors as the most significant factors related to lower levels of sexual activity and thus serve as protective factors. The factors identified were dual-parent families, a higher SES, residing in rural areas, higher school performance, concerns about the community, and higher religiosity. High parental expectations were a significant protective factor for males but not for females. Other researchers have found that less parental attachment is associated with greater numbers of sexual partners for the adolescent off-spring. The Lammers’ study supports the notion that sexual relationships may be a proxy measure for family closeness when the latter does not exist (Walsh, 199429). As noted previously, Sieving (2000) found that specific communication was protective. Adolescents' perceptions of maternal disapproval, together with high levels of 28 29 . Daniel F. Perkins;Tom Luster;Francisco A. Villarruel;Stephen Small, 1998. J of Marriage and family. Walsh A. Parental attachment, drug use, and facultative sexual strategies. Soc Biol 1994;42:95–107. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 25 mother-child connectedness were directly and independently associated with delays in first sexual intercourse. Thus, maternal disapproval of sexual intercourse, along with mother-child relationships that were characterized by high levels of warmth and closeness, appeared to be important protective factors for delaying the onset of sexual intercourse in adolescence. Of interest was the differential effect of maternal closeness for boys and girls. Maternal closeness was protective for boys, but not girls in this study, while disapproval was not gender specific in its effect in this particular study. The willingness of parents to discuss sex and sex related issues is an important factor in helping adolescent girls develop motivation and the vocabulary necessary to discuss safe sex practices with their partners. Of 522 sexually active African American teenage females who participated in one study, those who rarely spoke with their parent or parents about sexual issues were four times less likely to talk to their partners about condom use, as well (Crosby, 200230). Not talking about sex can be consequential because adolescents are more likely to be influenced by other sources of information, particularly peers. In Whitaker’s study, adolescents who did not discuss sex or condoms with their mothers showed a stronger correspondence between peer norms and their own behavior compared with adolescents who did discuss sex or condoms with their mothers. If peers encourage and model irresponsible behavior, risky sexual activity can be more likely31. As noted by DiClemente (2001), psychological distress is also related to a lack 30 March issue of Health Education and Behavior; http://proquest.umi.com/pqdlink?Ver=1&Exp=07-012003&REQ=3&Cert=8RkgPFRptdRru2FUUWKslyx3823faG7XRZT3W15CuisqD5QwNI3hsZ2NPjWG6 z0lLXXzdQIXCMe0KuN0LZpl0g--&JSEnabled=1&Pub=22101 31 5.Whitaker DJ, Miller KS. "Parent-adolescent discussions about sex and condoms: impact of peer influences on sexual risk behavior." Manuscript submitted for publication. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 26 of communication between sex partners, which reduces condom use and increases the risk of pregnancy32. The timing of mother-adolescent discussions about condoms appeared to be critical in a study by Miller et al (1998). Adolescents who talked with their mothers before their first sexual encounter were 3 times more likely to use a condom than adolescents who did not talk with their mothers. The authors noted that this was important because condom use at first intercourse strongly predicted future use. Adolescents who used condoms at first intercourse were 20 times more likely to use condoms regularly in subsequent sexual activity33. Not only do communication patterns impact sexual activity and thus risk for pregnancy, but the accumulation of risk factors within specific social systems appears to add risk (Miller et al, 200034). Miller describes a model in which risk factors from three types of systems are influential in the lives of adolescents. The three systems (individual, family and extra-familial) were analyzed with respect to the relationship of specific risk factors on outcomes, within each system. Self attitudes and beliefs, family system relationships, and extrafamilial relationships were each related to risk factors. As the number of systems with risk factors present increased, so did the risk of adolescent sexual behavior. This suggested that the broader the scope of risk factors, the more risk there is. 32 We are in no way legitimizing premarital sex by presenting these findings. 4.Miller KS, Levin ML, Whitaker DJ, Xu X. "Patterns of condom use among adolescents: the impact of maternal-adolescent communication." American Journal of Public Health 1998 Oct; 88(10): 1542-1544. 33 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 27 Further, a recent review by Reptti et al (2002) found overwhelming evidence that children who grow up in “risky families” are at a greater risk for the development of physical and mental health problems over time . Risky families are characterized by conflict and aggression and by relationships that are cold, unsupportive, and neglectful. These family characteristics create vulnerabilities and/or interact with genetically based vulnerabilities in offspring that produce disruptions in psychosocial functioning (specifically emotion processing and social competence), as well as disruptions in stressresponsive biological regulatory systems, and poor health behaviors. This profile leads to accumulating risk for mental health disorders, major chronic diseases, and early mortality. Children who grow up in risky families are more likely as teenagers and adults to engage in risky sexual behavior, as well as drug and alcohol abuse, smoking, aggressive, anti-social behavior, depression, anxiety and suicide. The authors interpreted their findings to suggest that risky sexual behavior (and substance abuse) may help these adolescents compensate for their emotional, social and biological deficiencies (Repetti, et al, 2002). Early and promiscuous sexual behavior and substance use may help adolescents manage negative emotions and feel accepted in the absence of adequate emotion coping strategies or social skills. Supportive and nurturing family environments might encourage appropriate social skills to help children gain acceptance by their peers and regulate their emotions. Children who are most lacking in social skills problem-solving and conflict-management skills seem to be most likely to turn to substance abuse or risky sexual behavior as a way to gain acceptance. Miller, K. S., R. Forehand, et al. (2000). “Adolescent sexual behavior in two ethnic minority groups: a multisystem perspective.” Adolescence 35(138): 313-33. 34 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 28 Family Religious Values Religiosity seems to influence family attitudes and behavior while, at the same time, family experiences and values influence religious participation and commitment (Thornton 1985a; Thornton et al. 1992). People with high levels of religious involvement and commitment tend to express lower levels of acceptance of divorce, cohabitation, premarital sex, unmarried childbearing, abortion, not marrying, and remaining childless (Thornton 1985a, 1985b; Thornton and Camburn 1987, 1989; Axinn and Thornton 1993; Sweet and Bumpass 1990b; Marsiglio and Shehan 1993; Tanfer and Price-Spratlin 1992; Rhodes 1985; Lye and Waldron 1993). As noted above, parental values are important influences on children’s behavior. Therefore, parents’ religiosity and values in turn affect children’s values and behavior. Many studies have noted that religious involvement is both protective when it is high (see Miller, 2001) and a risk factor when low (see Perkins, 1998). However, as noted above, some aspects of personal religiosity might also slightly increase the risk of pregnancy because of negative attitudes towards contraception (and specifically, condum use). Second Pregnancies Social factors were found to be important in preventing a second pregnancy (Manlove et al, 2000). In a sample of 564 high school-age mothers who were followed from 1988 to 1994, a combination of staying in school, living at home with their parents, and (among older teen mothers) being engaged in educational or work activities were factors associated with postponing a subsequent birth. Those teenage mothers who were DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 29 able to complete their high school diploma, or even their GED, were also less likely to have a 2nd teen birth. Although supportive and nurturing family environments are important for protection against a myriad of psycho-social maladjustment problems, one caveat to teen mothers living at home is the increase in risk for siblings living in the home with a niece or nephew. Past research has revealed that having a sister who gave birth as a teenager is associated with increases in young people's likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behavior. In analyses controlling for background factors, females with many parenting sisters had increased levels of behavioral problems (school problems, drug or alcohol use, and delinquent behavior) and an elevated likelihood of being sexually experienced (East & Kiernan, 200135). Having lived with two or more parenting sisters (as opposed to having lived with only one) was related to more permissive sexual and childbearing attitudes among young women and to earlier first intercourse among young men. Males with a sister who gave birth at a young age had elevated levels of delinquent behavior and promiscuous sexual behavior. These data were collected from 1,510 predominantly Hispanic and black 11-17-year-olds in a California program for youths who have at least one pregnant or parenting sister. Thus, as the number of teenage parenting sisters rises, youths'--particularly females'--risk of pregnancy involvement increases beyond the level associated with having only one teenage parenting sister. It is difficult to know if these data represent a specific risk or a marker. 35 Risks among youths who have multiple sisters who were adolescent parents.” Family Planning Perspectives 33(2): 75-80. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 30 Interpersonal violence was also shown to be associated with repeat pregnancies among low-income adolescents Jacoby et al, 199936). In a sample of 100 women aged 13-21, the experience of any form of physical or sexual violence during the study interval was associated with rapid, repeat pregnancy (RRP) within 12 months and 18 months. Other previously reported predictors of RRP, including family stress, financial stress, and other environmental stressors did not reach statistical significance at either 12 months or 18 month point for this sample. However, the relatively small sample size could have affected the outcome. School Factors Poor grades is frequently cited as being a risk factor for teen pregnancy (see Perkins, 199837). Moore (1998) found that being held back in school and repeatedly changing schools were both risks for pregnancy. Manlove (2000) found that dropping out of school doubled the risk of teenage birth, although this is confounded by the fact that many pregnant girls dropout because of their pregnancy (they noted that this trend has subsided considerably). Perkins also noted that unsupportive and a discouraging school environment increased the risks of pregnancy (1998). Three school-related factors were associated with some delay in sexual debut in Resnick’s study (1997): 1) higher levels of connectedness to school; 2) attending a parochial school; and 3) attending a school with high overall average daily attendance (Resnick, 1997). Consistent with this, a substantial level of involvement in school clubs Jacoby, M., D. Gorenflo, et al. (1999). “Rapid repeat pregnancy and experiences of interpersonal violence among low-income adolescents.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 16(4): 318-21. 36 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 31 and religious organizations was associated with a lower risk of school-age motherhood and thus served as protective factors in Moore's study (1998). Higher school performance showed a significant association with lower levels of sexual activity across all age groups in Lammers’ study (Lammers, 2000). Social Attitudes and Values Adolescent childbearing is by no means a unique phenomena in the world. However, our culture has deemed it to be a generally negative value, particularly when out of wedlock. Every society has a set of rules or norms that tells people how they ought to behave and conduct various aspects of their lives, including marriage and childbearing. While these normative systems are frequently tolerant of a range of behaviors, they include sanctions for those who stray beyond the accepted limits (Marini 1984; Klassen et al. 1989 in Thornton38). Also, as individuals grow up they internalize values, attitudes, and beliefs concerning family and personal issues. Both collective norms and individual values and attitudes define the meaning, behavior, and sentiment associated with marriage and childbearing. Thornton (1995) notes that the shifts in values, attitudes, and norms concerning a wide range of family issues, including marriage, sexuality, and childbearing have led to an expansion of the range of individual choices people feel are acceptable. This is reflected in a relaxation of the social rules for many dimensions of family and personal behavior. “There has been a substantial and widespread weakening of the normative 37 . Daniel F. Perkins;Tom Luster;Francisco A. Villarruel;Stephen Small, 1998. J of Marriage and family. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 32 imperative to get married, to stay married, to have children, and to maintain separate roles for males and females. In addition, attitudes and norms prohibiting abortion, premarital sexual relationships, and childbearing outside of marriage have dramatically receded" (Thornton, 1995, p. 219). Thus, many behaviors that were previously frowned upon and controlled by social forces have become accepted by substantial numbers of Americans (Thornton 1989; Cherlin 1992; Pagnini and Rindfuss 1993; Schulenberg et al. 1995; Hayes 1987). This widening of socially accepted limits has been one factor in the increase of sexual behavior. As noted above, other forms of social control are now coming into effective use (e.g., education, birth control techniques) which in turn are beginning to show some effectiveness in reducing pregnancy. On the other hand, Beerman and Bruckner (2001) found some support for the idea of manipulating social values as a means of protection against early pregnancy. Their study of virginity pledges among a small group of adolescents was widely publicized as a finding for abstinence-only education. However, their findings have been interpreted as the effect of a small group under certain conditions. When too few or too many students pledged, the effectiveness was not noted. Such pledges appeared to work for 14 and 15year olds within an identifiable group or clique, and for only up to 18 months. A noted ‘unwanted side effect’ in this study was a reduction in condom use by the successful pledge group members when sexual activity was begun (see Risman and Schwartz, 2002 38 Thornton, A. (1995). Attitudes, Values, and Norms Related to Nonmarital Fertility. Report to Congress on out-of wedlock childbearing. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 95-1257. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/wedlock.pdf. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 33 for critique). This reduction in condum use was consistent with Zaleski and Schiaffino's findings as well (2000). CULTURAL Cultural factors are macro-social and meta-social factors. These factors operate differently than social interpersonal or community social factors by virtue of their ubiquity. These include (but are not limited to) socio-economic status, policy-related or governmental factors such as laws, and media influences. Socioeconomic Status (SES) Socioeconomic status is at the crossroads between social and cultural factors. The relationship between poverty and teen pregnancy has been well-established and continues to find support. Hogan et al.39 reported that low-income parents found more difficulties in providing on-site and off-site supervision to adolescents. As in previous studies (Mott, 199640), a higher SES was associated with postponing sexual intercourse. Lammers (2000) found that higher SES was associated with lower levels of sexual activity. The higher income family may have more resources that allow for parental supervision. However, residing in a rural area was a protective factor in her study as well. 39 Hogan D, Kitagawa E. The impact of social status, family structure and neighborhood on fertility of black adolescents. Am J Sociol 1985;90:825–55. 40 Mott F, Fondell M, Hu P, et al. The determinants of first sex by age 14 in a high risk adolescent population. Fam Plann Perspect 1996;28:13– 8 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 34 Texas is one of five states in the United States in which teen pregnancies exceed 70 per 1,000 females aged 15 to 17 years. In a study of demographic variables from the 1990 census, results indicated that unmarried teen births were positively related to low socioeconomic status, single-parent family households, and minority populations (Blake & Bentov, 200141). SES is also implicated in the reduction of teen pregnancies. Hogan et al (200042) analyzed survey data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth and suggested that the trend of increases in teenage motherhood has ended largely due to a halt in increases in the proportion of sexually active young women and substantial improvement in contraception, with the greatest improvements among those from advantageous family situations. Improvements in the family socioeconomic situations of young women have lessened the risk of teen motherhood, while changes in family structure have increased the risk. Hogan found that young women whose parents have more than a high school education, who live with both parents, and who attend church delay the timing of first sexual intercourse and are more likely to use a contraceptive (2000). Although prior research demonstrated that residence in a socio-economically disadvantaged neighborhoods increased young women's risk of bearing a child out of wedlock, few studies have explored the sequence of events accounting for this relationship to show what effect the SES factors had on pregnancy. Analyzing data from 41 B. J. Blake;L. Bentov, 2001. Geographical mapping of unmarried teen births and selected sociodemographic variables; 42 Hogan, D. P., R. Sun, et al. (2000). “Sexual and fertility behaviors of American females aged 15-19 years: 1985, 1990, and 1995.” American Journal of Public Health 90(9): 1421-5. DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 35 the National Survey of Children on 535 women, Scott et al (2001) found that community socio-economic status had little effect on the likelihood that unmarried adolescent women would become pregnant. However, adolescent girls who were pregnant before marriage and who lived in poor communities were less likely (than those in wealthier neighborhoods) to voluntarily terminate a pregnancy. Thus, differences in premarital fertility rates across neighborhoods of varying socio-economic status appeared to result largely from differences in abortion rates. Compared to White women, Black women were more likely to become premaritally pregnant and less likely to marry before childbirth. Parental education was related to premarital fertility rates, due to both reduced rates of premarital pregnancy and by an increase in the likelihood of abortion. (Scott et al, 2001) Group-Think The perception of generalized behavior can impact individual behavior, particularly during adolescence, and the perception that ‘everybody is doing it’ is widespread. In two Kaiser Family Foundation surveys, both adults and teens overestimated the percent of teens who were sexually experienced. Adults estimated that 69 percent of teens had sex by age 15, and teens estimated 38 per-cent. However, data from both the National Survey of Family Growth and the National Survey of Adolescent Males showed that 25 to 27 percent of teens are actually sexually experienced by that age. Moreover, not all sexually experienced teens are currently sexually active. While 50 percent of students in grades 9-12 reported ever having had sex (Youth Risk Behavior DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 36 Survey, 1999), 36 percent of students had sexual intercourse in the past 3 months prior to the survey. Mass Media Mass media exposure and identification among young people have been shown to be related to attitudes and behaviors concerning sex and attitudes and perceptions concerning marriage, divorce, and nonmarital childbearing (Strasburger 1989, 1995; Brown and Newcomer 1991; Peterson et al. 1991; Zillmann 1994; Carveth and Alexander 1985). However, the current available research is unable to establish the cause and effect relationships connecting media exposure to sexual attitudes and behavior (Thornton, 1995). However, there are good reasons to believe a relationship exists between mass media exposure and sexual behavior and attitudes (Greenberg et al. 1993; Hayes 1987; Strasburger 1989, 1995). Both adolescents and adults acknowledge that television plays an important role in shaping attitudes and behavior (Strasburger 1995; Greenberg et al. 1993; Brown and Newcomer 1991). For example, four-fifths of adults say that television influences values and behavior. At the same time, two-thirds of these adults say that television does not give teenagers a realistic view of sex; and nearly two-thirds believe that television encourages teenagers to become sexually active (Strasburger 1989). DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 37 In reality, the presence of sexual themes in media is significant. The Kaiser Family Foundation survey (199943) documented trends in programming that reflected significant sexual content - at that time. Fifty-four percent of all shows contained talk about sex, and 23% of all shows contained depictions of sexual behavior. Seven percent of all shows contained scenes in which sexual intercourse was either depicted or strongly implied. In the one-week sample analyzed for this study, there were 71 scenes in which intercourse was strongly implied, and 17 scenes in which intercourse was actually depicted, albeit "discreetly." Only a slim majority of intercourse scenes included characters who had an established relationship with one another. When intercourse occurred, it most often was presented without any strong consequences for those involved. In the minority of cases where consequences were clearly conveyed, positive outcomes were far more common than any negative results (e.g., the couple maintained a relationship). Advertising also contains a significant amount of sexual imagery, including the inappropriate use of children in provocative poses44. Research also shows that heavy exposure to media sex is associated with an increased perception of the frequency of sexual activity in the real world. As a result, television may function as a kind of "superpeer," normalizing these behaviors and, thus, encouraging them among teenagers45. 43 Kunkel, D, Cope, KM, Farinola, W., Biely, E Rollin, E, Donnerstein, E (1999). Sex on TV: A Biennial Report to the kaiser Family Foundation. KFF 44 Sexuality, Contraception, and the Media. PEDIATRICS Vol. 107 No. 1, pp. 191-194,;.]; Strasburger VC "Sex, drugs, rock'n'roll," and the media: are the media responsible for adolescent behavior? Adolesc Med 1997 45 Strasburger VC "Sex, drugs, rock'n'roll," and the media: are the media responsible for adolescent behavior? Adolesc Med 1997 DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 38 Music Television (MTV) and other sources of music videos often display suggestive sexual imagery. In one content analysis, 75% of concept videos (videos that tell a story) involved sexual imagery, and more than half involved violence, usually against women (Sherman et al, 1986). Experimental studies have found that viewing music videos may, in fact, influence adolescents' attitudes concerning early or risky sexual activity (Calfirn et al, 1993). Greater sexual content is also found in videos that depict alcohol use (DuRant et al, 1997). The connection between alcohol and drug use and risky sexual behavior is well known. Music lyrics have become increasingly sexually explicit as well (Christensen & Roberts, 1998), and at least 2 studies have shown a correlation between risky adolescent behaviors and a preference for heavy metal music (Arnette, 1991; Klein et al, 1993). In an attempt to identify the extent of participation in eight potentially risky behaviors, including sexual intercourse and the use of a variety of mass media, Klein et al (1993) conducted a large in-home survey. Adolescents who had engaged in more risky behaviors listened to the radio and watched music videos and movies on television more frequently than those who had engaged in fewer risky behaviors, regardless of race, gender, or parents' education. White male adolescents who reported engaging in five or more risky behaviors were most likely to name a heavy metal music group as their favorite. Sports and music magazines were most likely to be read by adolescents who had engaged in many risky behaviors. CONCLUSION DRAFT: Pregnancy risks, p. 39 Risks of teen-aged pregnancy are multifactorial and multifaceted. Studies have documented a variety of interactions, patterns and situations that cross psychological, social and cultural realities. Biological factors have yet to be clearly demonstrated, although some biologically-based characteristics of individuals are noteworthy, such as early maturation. There is some indication that risks are also cumulative and cut across behaviors and problems. Because the outcome of pregnancy is age-related and occurs in adolescence, the majority of identified risks occur during adolescence, and reflect the emerging social-ness of teenagers. Mounting evidence points to the positive role of family influences, particularly those supported by stable institutions, such as religion. Lammers (2001) notes that the bulk factors associated with delays in the onset of sexual intercourse tend to be sociodemographic in nature, but school performance and family relationships point to both risks for pregnancy and protections from it, and are thus critical factors as well. The role of effective, enduring relationships, particularly within the family, but also within the community are important for reducing risks and conferring protection from early pregnancy.