Chapter 2A

advertisement

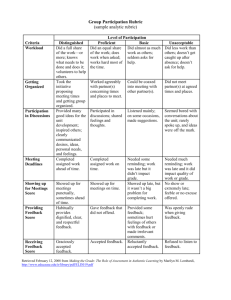

Foundation Skills Carl Rogers (1951) Concepts and Principles (1). The person’s subjective experience is one’s ultimate authority: -Subjective experiences occurring within the organism at a particular moment determine one’s behavior and judgments. -Conscious (unconscious) experiences can (can’t) be verbalized or imagined by the person. (2). We have an innate, active, controlling drive/motivation toward fulfillment of our potentials that enables us to maintain and enhance ourselves. -We have a self-actualizing/directional tendency, seeking new and various experiences to grow. (3) A Strong Need for Positive Regard: We have a learned or innate tendency to seek and need approval from others. Personality Development: (1). The Valuing Process in Infants: Infants use their innate actualizing tendency as a criterion in judging the worth of a given experience. Experiences that promote actualization are good and positively valued whereas experiences that hinder actualization are bad and negatively valued. This is called as “Organismic Valuing Process.” (EX) Infants value food when hungry but reject when satiated. (2). The Valuing Process in Adults: Adults’ valuing process is more complex. Our judgments and preferences about some objects and people are not stable but change because we constantly interact with others and our environments. Rogers claimed that we should ultimately trust the wisdom of our own bodies rather than listening to others because our feelings and intuitions may be wiser than our thinking or what we have learned from others. That is, we use our “Organismic Valuing Processes” completely, and then we will experience personal growth and will move toward actualizing our potentials. And then we become Fully Functioning Persons or Emerging Persons. Problems -Healthy individuals can verbalize and symbolize their subjective experiences accurately and completely whereas unhealthy individuals distort or repress their experiences and are unable to symbolize them accurately and sense them fully. -Self-actualizing and need for a positive regard from others. But we are at times antisocial, defensive, fearful, and immature, especially when we had faulty socialization practices. That is, society hinders movement toward selfactualization. Example (a) A strong need for a positive regard: Conditions of worth: We are worthwhile if we perform behaviors that others think are good and refrain from actions that others think are bad. Social Self: Self-concept that is largely based on what others think of or evaluate you. (b) We also have a strong need for self-actualization, which is governed by “Organismic Valuing Process.” In turn, we develop a True Self that is based on our actual feelings about our experiences. (c) Incongruence exists between the true self and the social-self/what we experiences. (d) Congruence can be obtained when we receive Unconditional Positive Regard, that is, a deep/genuine caring and nonjudgmental evaluations of our thoughts, feelings/behaviors by others. No environmental/external demands/pressure/critics makes us get in touch with our true self and move toward self-actualization. Our social selves and true selves are in harmony. *When incongruent, more likely to be defensive, pathological, and fail to actualize self. Foundation skills: Therapist’s behaviors that encourage a client to talk about his problems, needs, and concerns. 1. Listening -Not passive but active listening. Try to understand what the client is telling. Try to focus on nonverbal communication that is often more important that what is said. Be responsive in such a way that the client experiences being attended and understood. Listens to the client in such a way that the client is not judged and condemned for what was said. Listening to the client in a way that can encourage the client to congruently, genuinely, and nonJudgmentally listen to oneself and others (i.e., modeling). (a) Minimal Encouragement: Be a minimal encourager. -Too much encouragement can be too directive, disruptive, and controlling the conversation (i.e., an inviting smile or nod, “go on,” “yes,” “right,” “uh-huh,” “with whom.”). -The client is more likely to disclose oneself. (b) Paraphrasing: -Putting the client’s ideas or what the client said into the therapist’s own words, reflecting what the client verbally and nonverbally said and meant (“So you are telling me…, Sounds like you are feeling, thinking…, I hear you are saying…,). -It summarizes the client’s thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and problems. -Not too much paraphrasing (minimal encouragement). -Get permission (“let me share what I understood with you..) -Be willing to be fallible (good for rapport). The client does not expect the perfect accuracy. The clients are very forgiving. -Although it is at times very effective, repeating/reflecting exactly what the client said can be frustrating to the client. -This allows the client to feel that the therapist is really listening. -It gives a chance to correct therapist’s any misperception/misunderstanding (“Am I hearing you right?”). -It helps the client rehear and clarify what the client is thinking, feeling, and struggling about. -It invites further exploration. (c). Perception Checks -Clarify and underscore what the client just said. -More than paraphrasing. That is, it includes therapist’s inferences and interpretations. -Make sure to ask the client that your perception checks are correct. -Effective if it is given in the form of a fantasy or a metaphor (i.e., “you sound like you are inside a pressure cooker. One more problem will blow the top off. How it feels to you?”) (d). Summaries -Longer than paraphrasing and perception checks. -Clarify what the client has been saying and help them sort things out. -Covey your understanding of the client. -Encourage the client to further explore important issues. -Usually in the end of session. (i.e., let see if I follow you….”) (e). I-Statements (i.e., I feel uncomfortable telling what you need to do.”) -To encourage the client to own his or her feelings and thoughts. -It relieves the pressure on the client. -Help the client understand what they are experiencing is not unusual. -Encourage the client to explore his or her issues more deeply. -Not uninvolved observer but a real person. -Not too much I statement. 2. Problem-solving (a) Goal Setting: Identify problems and set up mutually agreed therapeutic goals. -Realistic, possible, practical, short or long term? -Encourage them the problems can be solved, but do not mislead them to believe that you will do the work for them (“we will work together and it may take time.”) (b) Using Questions: -Asking questions to sort out problems, collect data, and clarify their problems. -But not in a way controlling, directing, or interrupting the flow of interview. (i.e., “What was it like?” than “What was it?) -Open-ended question (“what brings you here?), asking for clarification (i.e., not because they did not say right), avoid yes or no questions, not pushing, ask questions in a way of constructing new alternatives, not in a way of changing subject abruptly (“That makes me wonder about your relationship with other people.”) (c) Feedback: -Be patient in giving your feedback. -When the client solicits -Be concrete and specific -Non-judgmental -Check how the client receives that. (d) Advice -Can make the client dependent. -Be cautious -Lead your client to say what you want to say. 3. Dealing with Feelings: Help them identify, verbalize, recognize, and differentiate various feelings. (a) Timing: Timing for “hot cognitions and feelings.” (b) Therapist Feelings: -Be sensitive to your own feelings (i.e., disgusted, boring, unpleasant) and do not let your feelings interfere with therapy or interview (Your client can know your feelings based on nonverbal cues). (c) Sharing your feelings -Disclosing your feelings at times therapeutic.