hill agriculture research project (harp), nepal

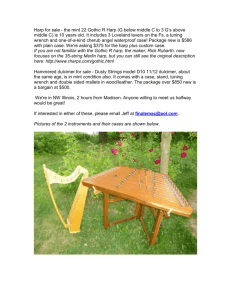

advertisement