FINAL Art of Teaching Dance Practice Course Notes for 2012

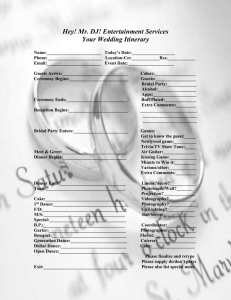

advertisement