Active Listening - Restorative Justice Scotland

advertisement

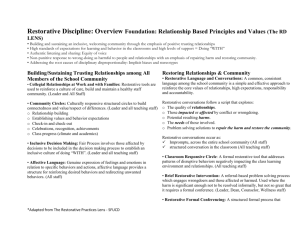

An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland (Version 1.10) 2008 The following is a text-only version of most of the accompanying powerpoint presentation. It has been produced on the assumption that some readers find it easier to read a printed version. Contents 1. What is it? 1.1 Restorative Justice Values 1.2 Restorative Justice Skills 1.3 Restorative Justice Processes 2. What can it do? 2.1 Person Harmed 2.2 Person Responsible 2.3 Community 3. What works? 2.1 Context 2.2 Suitability 2.3 Best Practice 2.4 Effectiveness The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 2 1. What is it? 1.1 Restorative Justice Values* In the following, the values with an asterisk have been adapted from “Statement of Restorative Justice Values and Processes,” New Zealand RJ Network (March 2004). Empowerment* Restorative justice recognises that . . . All human beings require a degree of self-determination and autonomy in their lives; that harmful behaviour robs those affected of this power, since another person has exerted control over them without their consent; and that they can be re-empowered by taking an active role in determining what their needs are and how these should be met; Those who have caused the harm should be empowered to take personal responsibility for their actions, to do what they can to remedy the harm they have inflicted, and to begin a rehabilitative and re-integrative process. Interconnectedness* Restorative justice recognises that . . . Society (or the institution) shares responsibility for its members and for many of the underlying causes that give rise to harmful behaviour; and that there is therefore a shared responsibility to help restore those who have been harmed and reintegrate those responsible; The person harmed and the person responsible are uniquely bonded together by their shared participation in the incident, and in certain respects they hold the key to each other’s recovery. Non-Retributive In restorative justice . . . The process and the outcome makes sense to all participants as helping to repair or address the harm - materially or symbolically – and not as an attempt to inflict punishment or retribution (understood as the deliberate imposition of pain and suffering as a form of ‘payback’ or ‘just deserts’). The process may be burdensome, uncomfortable or difficult for the person responsible (e.g. meeting the person harmed or carrying out a restorative task); but that burden must be treated and understood by all participants as only a side-effect of the restorative action, not its main point. Fairness In restorative justice . . . All participants feel that the facilitator is impartial, that they are given an equal voice in the process, that their needs are heard and taken seriously, and that any reparative agreements are proportionate to the harm done, non-degrading, achievable and constructive. Fairness is not, as it is in the legal system, conceived as “the consistent application of rules and procedures (e.g. the same sentence/process for the same crime)”. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 3 Hope* Restorative justice. . . Recognises that no matter how severe the wrongdoing, it is always possible for the community to respond in ways that lend strength to those who are suffering and that promote healing and change; Does not penalise past actions, but instead addresses present needs and equips people to move forward with their lives; Nurtures hope: the hope of healing for persons harmed, the hope of change for those responsible, and the hope of greater civility for society. Respect* In Restorative Justice . . . All participants are spoken to and treated in a way that upholds and enhances their inherent and equal worth and dignity; The process does not discriminate or show partiality on the basis of their actions, good or bad, or of their race, culture, gender, sexual orientation, age, beliefs or status in society; and It engenders trust and good faith between them. Humility* In Restorative Justice. . . Empathy, mutual care and the recognition that participants have more in common as flawed and frail human beings than what divides them are encouraged; Those who facilitate and recommend the process acknowledge and allow for the possibility that unintended consequences may follow from their interventions. Accountability* In Restorative Justice. . . The person who has played a role in causing harm chooses to accept responsibility for their actions; and This acceptance is demonstrated by acknowledging their role in what happened, clarifying what happened and why, expressing sincere remorse for their actions, addressing or repairing the harm that was caused, and taking steps that will help them to refrain from similar actions in the future. Reintegration In Restorative Justice. . . Taking responsibility, making amends and changing one’s ways are recognised and supported as ways of enabling a person to be reintegrated, that is, re-accepted or ‘welcomed back’ as a person of equal moral standing; Any aspect of the process that might continue or increase the isolation, exclusion, stigmatisation and estrangement of any participant is carefully and deliberately avoided. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 4 Mutuality In Restorative Justice. . . The person harmed and the person responsible are given an equal and genuine opportunity to participate. The process aims to meet the respective needs, wishes and circumstances of all participants. Voluntariness In Restorative Justice . . . Participation is freely chosen; otherwise, it will lack the authenticity, trust and sincerity that is necessary for genuine moral engagement, emotional responses, consensual decision-making and behavioural change. No participant is coerced, pressured, or induced by unfair means to take up the invitation to have the process explained to them, to (continue to) participate in any process, to enter into any agreements as part of the restorative outcome. Participation* In Restorative Justice . . . The person harmed and the person responsible for the incident are given the opportunity to be the principal speakers and decision-makers. Members of their respective communities of care are given the opportunity to play a supportive role. All participants are regarded as having something valuable to contribute to the process. 1.2 Restorative Justice Skills Active Listening Giving people a safe space to say what they need to say Showing that you are listening by your body language Allowing them to be angry and upset without ‘fixing’, ‘rescuing’ or ‘blaming’ them Asking appropriate and encouraging questions Feeding back accurately Self-Awareness Paying attention to your own feelings and behaviour Being aware of your personal ‘hooks’ (things that stop you in your tracks) and ‘triggers’ (things that set you off) Being aware of your own strengths and weaknesses The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 5 Problem-Solving Finding the facts Identifying the problems Clarifying the solutions Working out plans of action Assertiveness Being able to present your role and needs in the process clearly and respectfully Being prepared to establish ground rules Being willing to intervene if these rules are not adhered to Impartiality Demonstrating that you are not siding with any one participant Showing that you are concerned to ensure that the needs and interests of all participants are met in the process Genuineness Being oneself (open, transparent, authentic) Not hiding behind a mask of professionalism Being sincere, warm and non-defensive. Building Rapport Presenting yourself as a professional person who takes the issue seriously Creating an atmosphere in which the participants feel they can trust you and that you genuinely care about their views and feelings Giving the participants a chance to make their own decisions at their own pace Non-Discriminatory Understanding how issues such as racism, ageism, homophobia and sexism play a part in conflict or offending behaviour Being aware of different cultural needs and perspectives Being able to work with a diversity of people, ensuring that they are treated equally Conflict Management Staying calm Distinguishing between arguments and disagreements Encouraging communication, even when emotions are running high Defusing anger Suggesting ‘time out’ Using I-messages The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 6 Professionalism Taking the work seriously Being well prepared Devoting as much time and energy as is necessary Always looking for ways to improve and develop The ability to learn from your experiences (good and bad) Creating Safety The ability to create a ‘place’ or an atmosphere in which people feel they can be open and honest To ensure that people don’t feel shamed, humiliated or put down in any way To honour and respect the feelings and words of each participant Flexibility The ability to change the process in order to meet the needs of each situation Always putting people’s needs before rules or ‘the way we have always done it’ Listening carefully to how people are experiencing the process, and responding quickly to their requests or concerns Facilitation Assisting the participants to communicate, to listen to each other, to express facts, feelings and concerns Making sure that you speak or intervene as little as possible in any restorative meeting Creating a space in which participants feel that the dialogue is owned by them and that it is as natural as possible Presentation Communicating ideas in direct and simple ways Having all the relevant written materials with you (e.g. leaflets) Knowing the material thoroughly, so that you can speak confidently and authoritatively Being aware of how your own body language and gestures can communicate your thoughts and feelings to others Reframing Being able to re-word what someone has said so that the other participants can hear what they really meant (e.g. ‘So what you are saying is . . . ) Taking out negatives, accusations, confusing grammar etc., and making what is said clear, positive and constructive The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 7 Creativity The ability to come up with new ideas or compromise solutions that no one has thought of To try different ways of working where necessary To be adaptable to changing situations Empathy The ability to step into a participant’s world or frame of reference – as if you are in their shoes – without losing your objectivity To be open to understanding how they might be feeling from their point of view 1.3 Restorative Justice Processes Every restorative justice process aims to provide a ‘safe place’ where all those involved in an incident that has caused harm can speak openly and honestly about three topics: FACTS What happened? Who was responsible? Why did it happen? CONSEQUENCES Who was harmed? How were they affected? How do they feel now? FUTURE How can the harm be addressed or repaired? How can this behaviour be prevented? There are a range of restorative justice processes, each of which is designed to meet the needs and wishes of participants. Use of terms There is a broad consensus in Scotland that ‘restorative justice’ refers to processes that seek to address or repair harm. Consensus on the use of the term ‘restorative practices’ has not (yet) been established. Some hold that ‘restorative justice’ and ‘restorative practice’ are synonymous.* Others hold that ‘restorative justice’ is a subset of ‘restorative practices.’ For example, in the context of some schools ‘restorative practice’ is used to encompass not only restorative justice processes (in blue) but also a wide range of other processes (in red). The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk 8 An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) Different contexts and terminologies Schools Police Warnings Youth Justice Diversion from Prosecution Prisons Restorative Justice Conferences Restorative Police Warning Conferences Restorative Justice Conferences - Restorative Justice Conferences Restorative Meetings - Face-to-Face Meetings Face-to-Face Meetings Restorative Meetings Shuttle dialogue Restorative Police Warnings Shuttle dialogue Shuttle dialogue Shuttle dialogue Victim Awareness - Victim Awareness - Victim Awareness Support for Persons Harmed - Support for Persons Harmed - Support for Persons Harmed Restorative Conversations - - - Restorative Conversations Restorative Justice Circles - - - Restorative Justice Circles - - Restorative FGCs - - The term ‘restorative practice’ is currently used in the context of schools to encompass not only restorative justice processes, but also conflict resolution, informal decision-making, relationship-building, and other similar processes. Schools Youth Families Neighborhood Employment Civil or Commercial Prisons Mediation Youth Homelessness Mediation Family Mediation Community Mediation Workplace Mediation Alternative Dispute Resolution - Peer Mediation - - - Peer Mediation - - ProblemSolving Circles - - - - - CommunityBuilding Circles Check-in Circles - - - - - Family Group Conferences Family Group Conferences Family Group Conferences - - - CommunityBuilding Circles Family Group Conferences Restorative Justice Conferences Description: Restorative Justice Conferences are normally led by two facilitators and are attended by the person(s) harmed, the person(s) responsible, their respective support persons and other affected persons. Support persons can include family members, friends and/or professionals (e.g. social worker, school staff, youth worker, victim support volunteer, and so on). The facilitator carefully prepares all participants before they meet so as to ensure it is a safe and productive process. The conference may result in an Action Plan in which the person responsible agrees to do a reparative task and/or take steps to address the underlying causes of their behaviour (which may involve the assistance and agreement of professionals). Conferences are ordinarily used only where the incident has caused significant harm to an identifiable person(s) and when the involvement of family members or other support persons is seen as critical to a positive outcome. Some schools have set up partnerships with local Restorative Justice Services so that if a conference is required, the Service can provide one of its RJ workers to serve as the facilitator. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 9 Example: The young person was charged with shoplifting from a small business, run by a husband and wife team. The facilitator met with all those involved to explain their options. They all agreed to participate in a conference, including the young person’s parents. The facilitator then spent several sessions with each participant, helping them to prepare for the meeting. At the conference the young person began by saying what he had done and why he had done it. The shop owners expressed how it had made them feel – their fear, the anger and their suspicion when young people were in their shop. The young person listened and then apologised for what he had done. His parents said how sorry they were too, and that they were trying to resolve issues at home. The shop owners felt that the young person had understood the impact of his actions, and that the apology was sincere. So they suggested that, as reparation, he could work at their shop for four Saturdays. Two of the Saturdays would pay for the stolen items, and he could keep his pay for the other two days. The young person completed his four Saturdays. The shop owners felt that their loss was restored. They were so pleased that they offered him a job at the shop. He couldn’t accept, because he was starting college. But he did get a good reference. See http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk/YJ1.htm for the full version of this case. Face-to-Face Meetings Description: Face-to-Face Meetings can be led by either one or two facilitators and are attended by only the person(s) harmed and the person(s) responsible. The facilitator carefully prepares both participants before they meet so as to ensure it is a safe and productive process. The meeting may result in an Action Plan in which the person responsible agrees to do a reparative task and/or take steps to address the underlying causes of their behaviour. This kind of process is used when both participants agree that the incident can be effectively resolved without bringing support people to the meeting. For example, they may feel that the incident was not serious enough, or they would prefer to talk in private, or they feel that bringing support people could complicate the issue or threaten the safety of the process. Face-to-Face Meetings are often used in cases where people have harmed each other as a result of conflict (e.g. a fight). In such cases, the process can be used both to resolve the underlying conflict, as well as address the harm done. Example: The young person was involved in breaking numerous school windows deliberately. The young person and the person harmed (the janitor) agreed to participate in a face-to-face meeting. During the Preparation the janitor said he wanted the young person to stop breaking the windows and to stop the abusive gestures and comments when he was going about his janitorial duties.At the Meeting the janitor challenged the young person on his truanting. The young person explained he had not been given a new school since his exclusion some months previously. He took full responsibility for leading the other young people into the vandalism. The janitor said how he felt about the abuse. The young person made a sincere apology and promised not to break the windows again. The Action Plan was to greet each other with respect and for the young person to stick in at school and make something of his life. The janitor assumed that the young person was truanting when he was not. The young person did not understand that the janitor’s feelings were hurt by his abusive gestures. Both gained respect for each other through their honesty, their understanding of the other person’s position, and their commitment to getting a resolution to a difficult situation, face to face. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 10 Shuttle dialogue Description: Shuttle dialogue involves a facilitator acting as a go-between for the person(s) harmed and the person(s) responsible. The facilitator carefully prepares both participants before they exchange communication, so as to ensure it is a safe and productive process. This process may result in the participants agreeing on an Action Plan in which the person responsible agrees to write a letter of apology, complete a reparative task and/or take steps to address the underlying causes of their behaviour. This process is used when one or both participants do not wish to communicate in a meeting, or it is felt that it would be unsafe or impractical to do so. The communication can be take place by letters, audio/visual tape recordings, or by the facilitator reporting directly. Example: It began with a group of young people throwing stones at a house window. Inside was a 13 year old girl and her parents. All the young people attended same school as the girl, and had been bullying her constantly. The behaviour progressed into threats and intimidation. The abuse continued for almost an hour until the parents called the police. Two of the young people were referred to restorative justice. Both showed remorse for their actions from the start and wanted the opportunity to make amends. They completed victim awareness material and wrote letters of apology to the parents and the girl. The facilitator then met with the persons harmed to discuss their involvement with the service. They expressed their feelings of anger and fear. Since the incident they felt that they had been labelled "the neighbours from hell" through no fault of their own. Their daughter had to move school for fear of future bullying and intimidation, and found it difficult to go out. The facilitator asked if there was anything that could make their lives a bit easier. After some discussion, an agreement form regarding future behaviour was written up. Prior to this, the apology letters were read to the parents. They stated that they would accept the apology. They said it felt better that they were at least trying to do something. The future behaviour form was then shown to the two young people. Both agreed to comply with the request and also felt relieved that their apology had been accepted. The facilitator returned to the parents to show them the signed and agreed form. The parents said they felt much better and appreciated the support. Victim Awareness Description: Victim Awareness Programmes involve only the person responsible in one-to-one or groupwork sessions with a facilitator. The process may include voluntary reparative tasks and/or cognitive behavioural courses or modules (e.g. ‘gains and losses of offending’ exercise, anger management, substance misuse, etc.). In a restorative context, this process is used if (and only if) one participant does not wish to communicate with the other, or it is felt that doing so would be unsafe or inappropriate, or if the person harmed cannot be contacted or identified. Example: The incident involved a young male (age 14) assaulting another male (12) on the way home from school. It was reported to the police, and the Children’s Reporter referred the case to the local Restorative Justice Service. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 11 The facilitator met with the young person responsible for the offence, with his parents, to explain the service. The young person said he was really sorry for what he had done, and said he would like to apologise to the person harmed, if that would help. The facilitator then met with the person harmed and his parents. The parents were pleased to hear that the person responsible wanted to apologise, but – after talking it through with the facilitator - were not convinced that a meeting would help their child at this time. The facilitator explained that the person responsible would do a victim awareness programme instead, and the parents said they would like to know the outcome. So the facilitator helped the person responsible to work through the victim awareness material which took three half-hour sessions over two weeks. This involved him thinking about what happened and why, what the consequences were likely to have been for the other boy and his family, and what he needed to do to make sure it didn’t happen again. At the end, the facilitator informed the person harmed and his parents that the programme had been completed successfully. Support for Persons Harmed Description: Support for Persons Harmed is a process that, at present, is only used in prisons – but it could be used in any other context. The process involves a discussion between the facilitator and the person harmed, with the aim of addressing the hurt, fear and anger experienced by person harmed. The process also seeks to raise their awareness of how to protect themselves in the future, and to assess whether they require professional help in their recovery process. In a restorative context, this process is used if (and only if) the person harmed doesn't know, or doesn't want to reveal the identity of the person responsible, or doesn't want to communicate with them. Example: The person harmed (18 yrs old) had only been in the prison for 2 weeks. It was her first time inside, and she was not coping. Her cell mate was threatening to beat her up because she refused get her friend to bring in more ‘supplies’ when she came to visit; and now she was being given the silent treatment by the other girls in her unit. She was in such a state that she would start crying over almost anything, and was very fearful and anxious for her safety. She went to speak with her personnel officer about it, but only on condition that the officer would not report her cell mate, since that would only make her life worse. The officer found a private, safe place – a room in the chapel – to talk with her. The officer encouraged her to talk about what had happened, her responses and how she was feeling now – all the time affirming and validating what the person harmed was saying. The officer then asked her to reflect on what she could do to manage the situation, and how the prison establishment could help. They talked about anticipating feelings, responding assertively, and the possibility of re-location to another unit – which the person harmed quickly accepted. The discussion helped the person harmed to feel reassured that her responses were not uncommon, and that there was someone who she could turn to if she needed help again. The relocation also made an enormous difference, and the confidentiality of the process ensured there were no repercussions for her from her previous cell mate. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 12 Restorative Conversations Description: Restorative conversations are only used in an institutional context (schools and prisons). They are a five to ten minute discussion between a staff member and the person responsible. They are used immediately after a minor breach of rules that may have affected others, but which did not directly harm an identifiable person. Conversations are designed to create a learning experience. Instead of simply telling the person responsible what to think or how to behave, the facilitator leads them through a simple but structured dialogue, using open questions and reflective listening. The process is designed to enable the person responsible to think through the reasons for their behaviour, to reflect on how it might have affected other people, and to discover for themselves alternative ways of behaving in the future. Example: The incident involved a student coming 10 minutes late to class - for the third time. The teacher asked him to stay after class. Once all the other students had left, they both sat down. The teacher explained that she wanted to talk to the student about his coming late to class. She asked him what was happening – whether there was a reason for the lateness. The student explained that he ‘just needed to take some time out in between classes to get some fresh air’. The teacher explored why he was needing this, and it turned out that he was catching up with some of his friends from a different year. The teacher then asked the student how his being late was affecting him. He thought for a moment, and said that he was probably missing out on things in the class. The teacher asked how it might be affecting the class. He shrugged; and then, after a while, said that he guessed he was interrupting the other students’ concentration, and that it was probably annoying for the teacher. The teacher asked what him what he could do to make sure it didn’t continue. The student said that he would try to meet up with his friends during lunch instead. The teacher affirmed his decision and his willingness to talk it through. Restorative Justice Circles Description: Restorative Justice Circles are only used in an institutional context (schools, residential units and prisons); but they could also be used to address anti-social behaviour in the community. They are normally arranged when there has been an incident involving a number of individuals which has caused significant harm to themselves, other members of the institution (including staff) and the establishment (e.g. a riot, destroying facilities, etc.) As with any restorative process, the facilitator will carefully prepare all participants before they meet so as to ensure it is a safe and productive process. The circle process allows all those involved to discuss the incident openly and honestly in a safe and structured context. Restorative Justice Circles differ from other uses of the circle format (e.g. problem-solving circles, ‘check-in circles or circle-time) insofar as the explicit aim is to enable the participants to address the harm that has been caused by a specific incident. In other words, like every other restorative practice, the circle discussion is structured by a focus on the facts (what happened), the consequences (who has been affected) and the future (how can we stop this from happening again). The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 13 Example: Twelve young people were in a youth centre, participating in a group session. During the first part of the morning the fish started dying. By the following Monday, they were all dead. The staff arranged a restorative circle, and explained that they wanted to get an understanding of why this happened and to explore with the young people the consequences that this had on everyone. The circle lasted an hour and a half, which gave them plenty of time to reflect and explore the behaviour. Without being asked, the young people told the staff exactly what had happened, who took part and how the fish were poisoned. At the end, the young people concluded that they were all responsible because they were all in the youth centre but that some played a greater role than others (i.e. some did it, some watched and did nothing to stop it, and everyone else laughed or knew about it). It was agreed that some would pay £10 and others £1 to pay for the fish. The staff typed up a contract to this effect, and each young person signed. The process enabled staff to challenge the young people openly and use peer pressure in a positive way, by encouraging participants to take a lead role. The youth centre also gained £47 toward purchasing new fish that would not otherwise have happened. Restorative Family Group Conferences Description: Restorative Family Group Conferences are normally led by two facilitators and are attended by the the person responsible, his or her support persons, and professionals who are working with or may have some involvement with the person responsible. The facilitator carefully prepares all participants before they meet so as to ensure it is a safe and productive process. If there is an identifiable person harmed, the facilitator will ensure that they have the opportunity to convey to the person responsible (through the facilitator): (a) how the incident has affected them, and (b) any requests for a letter of apology, an explanation or reparation in the meeting. The facilitator may, if the person harmed wishes, feed back to them the outcome. In the meeting, the facts, the consequences and any reparative requests or arrangements are discussed first. Then the facilitator begins the standard three-part FGC process. Information Sharing: Professionals will present their perspective on the underlying causes of the offending behaviour and make clear what resources they can make available to the family to help them address these causes. Private Family Time: The family then meet privately to come up with a plan that will help to prevent the person responsible from re-offending (taking into account what the professionals have said) Agreeing the Plan: When they return to the meeting, they present their plan to the group, and it is then refined and written down. Example: The incident involved a young person (13) throwing stones at a passing GNER train. The police were called, and the case was referred by the Children’s Reporter to the local Restorative Justice Service. The Reporter indicated to the facilitator that there was an underlying care issue in this case that needed to be dealt with – preferably in an informal setting. The young person already had a social worker, and had been referred to the Hearing system for previous offences. Hence, the Reporter asked the facilitator to see whether a Restorative FGC might be a useful way of addressing the offence as well as helping the family to come up with a plan that might address the lack of adequate parental supervision - due to them working on Tuesday evenings and Saturdays. The facilitator met with the young person and his family, and they agreed to take part. GNER was contacted and they requested that the facilitator convey to the young person the potentially deadly consequences of stone throwing. They said they would accept a letter of apology, if the young person agreed to write one voluntarily. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 14 The meeting was held, with the young person, his parents, his grandparents, his uncle, his social worker and a youth worker present. The young person was genuinely sorry for what he had done. So the Action Plan included his agreeing to write a letter of apology to GNER. The family also agreed to make arrangements for the youth worker to take him to the youth club on Tuesday evenings, and for his grandparents and uncle to look after him on alternate Saturdays. Restorative Warning Description: Restorative Warnings are facilitated by trained police officers and are designed to deal quickly with minor first or second offences. The person responsible for the offence, together with their support persons, meet with a police officer for 20-30 minutes. The role of the police officer is to ensure that everyone can speak without interruption, in an open and honest manner, about the facts, the consequences, and the future. Whilst the person harmed does not attend a warning, they do have the opportunity to be informed of the outcome and, if all participants agree, to receive a letter of apology and, in some cases, appropriate reparation. Whilst most areas now offer restorative warnings, the aim is that they will replace Senior Police Officer warnings throughout Scotland by April 2006. [Note: “Police Restorative Warning Conferences” can also be held, but this process is identical to a Restorative (Justice) Conference, with the only difference being that the conference is either facilitated by a police officer or a police officer is present at the conference.] Examples: 1. Hoax 999 call Fourteen year old female made a hoax phone call requesting the Fire and Rescue Service attend a dwelling-house that was on fire. The RJ warning was administered jointly by Police and Fire and Rescue Service. The Fire Service showed a video to the youth. (The video involved a female placing a hoax 999 phone call to the fire service. The Fire engine arriving at the hoax call, and at the same time her friend has been trapped in a car crash, and needs the fire service to cut her out; because the fire service have attended the hoax phone call, which is at the other side of town, they don't make it in time and the girl dies.) The fire service also let her hear a hoax 999, and took her to the Control Room and explained the process when a hoax 999 call is received. Both the young person and mother felt the warning went well. 2. Breach of the Peace Fourteen year old male youth in possession of BB gun. Youth was pointing it to members of the public. Cautioned and charged with Breach of the Peace. Police administered RJ Warning. The youth was very remorseful for his actions. He thought what he was doing was not a crime. When informed of the consequences of his actions he could clearly see the wrong in his actions. It is in the opinion of the submitting officer the accused is a well behaved youth and will not re-offend. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 15 2. What can restorative justice do? 2.1 Person Harmed Needs of the person harmed that restorative justice can meet: Confidence To be able to trust the person(s) who are facilitating the process. To be satisfied with the way the incident was dealt with. To increase their confidence in the moral legitimacy and fairness of the institution or the justice system that has incorporated a restorative approach. Decision-Making To feel that they have a genuine, non-pressured and informed choice about whether to participate, based primarily on whether the process is likely to assist their own recovery. To regain a sense of control over their lives, especially where they feel this has been taken away from them - initially by the incident itself and then, perhaps, by the way in which the institution or justice system responded to the incident. To have their views about what needs be done taken into account in the decisionmaking. Procedural Justice To be treated in a fair and respectful way. To have a trained and competent facilitator who is impartial, ethical and unbiased. To participate in a carefully structured process that is designed to uphold the individual dignity and basic equality of all participants at every stage. To know that the process is flexible and open to revision, correction or modification by participants if appropriate. Information and Preparation To be given prompt and sufficient information about the way the incident is to be dealt with, the options available to them and possible outcomes. To feel that they are fully prepared for their role in the process. Answers and Impact To obtain answers to questions they have about what happened, who was responsible and why it happened. To have an opportunity to convey to the person responsible the emotional suffering and distress that their actions have caused. To feel that their experience and their responses have been validated. To know that telling their story is likely to have an impact on the person responsible, in terms of them facing up to what they have done, learning from the experience and changing their behaviour in the future. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 16 Apology To receive a sincere apology from the person responsible for the harm that they have caused. Material Restoration To have the financial and emotional value of their material losses acknowledged. To have these losses actually restored or amends made by the person responsible, including the return or repair of property and/or reparative tasks. Emotional Restoration To experience relief from or a reduction of the type of suffering and distress that is often caused by victimisation, including anger and bitterness, self-blame, diminished self-confidence, fear, anxiety, mistrust, vulnerability, the sense of being violated or disrespected and physical symptoms (headaches, sleeplessness, nightmares, etc). To feel empowered and strengthened by their involvement in an emotionally challenging and (potentially) unfamiliar process. To feel that they did what they needed to do to move on with their lives. 2.2 Person Responsible Needs of the person responsible that restorative justice can meet: Confidence To be able to trust the person(s) who are facilitating the process. To be satisfied with the way the incident was dealt with. To increase their confidence in the moral legitimacy and fairness of the institution or the justice system that has incorporated a restorative justice approach. Decision-Making To decide for themselves that they will take responsibility for the harm they have caused. To have their views and agreement taken into account in deciding what needs to be done to address or repair the harm. Procedural Justice To be treated in a fair and respectful way. To have a trained and competent facilitator who is impartial, ethical and unbiased. To participate in a carefully structured process that is designed to uphold the individual dignity and basic equality of all participants at every stage. To know that the process is flexible and open to revision, correction or modification by participants if appropriate. Information and Preparation The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 17 To be given prompt and sufficient information about the way the incident is to be dealt with, the options available to them and possible outcomes; To feel that they are fully prepared for their role in the process. Moral Development To learn that their actions have potentially harmful consequences for others. To develop their capacity to empathise with other people’s feelings. To more readily anticipate (and thus take steps to avoid) the shame and remorse they would feel if they harmed another person. To learn how to take responsibility and be accountable for their actions. To learn what it means to uphold the dignity and value of others, regardless of the cost. To learn what is involved in trying to repair relationships (courage, honesty, listening, vulnerability, apologising, and so on). To challenge the cognitive distortions that may have led up to the incident (excuses, blaming, justifications, revenge). Reintegration To be given the opportunity to take responsibility and make amends – and, as a consequence, to then be re-accepted or ‘welcomed back’ into the community. To engage in a process that sets out to diminish or put an end to the painful isolation, exclusion, stigmatisation and estrangement that they may be experiencing as a result of their actions. Material Restoration To gain a clear sense of the value that material possessions can have for others, in both financial and personal terms. To learn that moral responsibility and achieving reintegration can be difficult and costly – but at the same time fair and appropriate: e.g. addressing material harm may involve burdensome reparative tasks or the return and/or repair of property. Emotional Restoration To gain a powerful and persuasive impression of the suffering and distress that their behaviour caused to other people. To engage in a process that may help the person harmed in their process of recovery (e.g., answering questions about what happened and why can help the person harmed to let go of any self-blame; a sincere apology can have a positive affect on levels of anger or resentment, etc.). To engage in a process that may assist their own emotional recovery (e.g. release from personal guilt and shame, being ‘re-accepted’ by those around them, etc.). The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 18 2.3 Community Needs of the community* that restorative justice can meet: *The term ‘community’ is notoriously difficult to define. In this context, it is used to refer to a wide range of groupings: i.e. it can refer to the immediate family and friends of the persons harmed/responsible; and/or the wider circle of individuals/groups who are aware of or have been indirectly affected by the incident; and/or the social contexts or institutions in which the incident took place (e.g. neighborhood, school, prison, workplace, shopping center, etc.) Confidence To increase the community’s confidence in the moral legitimacy and fairness of their institution(s) or the justice system(s) that incorporate restorative justice approaches. To increase the confidence and capacity of communities to resolve their own conflicts and troubles, rather than resort to a ‘consumer’ approach to the police, formal disciplinary measures, courts and social services. Empowerment To have available an informal process in which relevant community members can directly participate and in which their views be taken into account in deciding what needs to be done. To have available methods of social control that do not divide, alienate and disable communities (e.g. coercion, threats, exclusion). To be able to draw on and strengthen community-based resources and solutions (e.g. appeals to conscience, the building and repair of relationships, support networks, and the free choices of those involved). Safety To recognise that community safety cannot be exclusively dependent on external deterrents (police presence, CCTV, wardens, etc.). To have (or be aware of) experiences that affirm the view that ongoing safety depends on internal / community-based deterrents: i.e. building relationships, treating others with respect, drawing upon local support networks, and repairing harm in a constructive way. Restoration To know that there is a process that will give those who cause material damage or emotional distress in the community the opportunity to repair or restore the harm done. To know that there is a way of responding to those who cause harm that does not humiliate, stigmatise or ‘outcast’ them, but rather aims to draw them back into the community and to support and encourage them in their efforts to make amends and change their behaviour. The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 19 3. What works? 3.1 Context Restorative Justice works best when they it is used alongside a range of other approaches that share the same values and skills, as in the diagram below Interpersonal Skills Active listening, empathy, assertiveness, courtesy, dealing with conflict, communication skills, accepting criticism, encouraging, supporting, respecting differences, taking responsibility, apologising, emotional literacy, cooperation, etc. Building and sustaining relationships Strengthening relationships Solving problems and challenges Resolving conflict Addressing harm Mentoring, Buddy Systems Checking-in Circles Problem-Solving Circles Pupil Councils, Family Led Decision Making Mediation, Peer Mediation Restorative Justice * Disciplinary Processes * Restorative Justice processes can be used either as an alternative to or in parallel with disciplinary processes. Please note that, in the model above, there are a number of clearly defined processes that should only be used in the situations for which they were designed – with the foundation stone being the consistent and widespread use of interpersonal or social skills. Restorative Justice has a distinct role to play in this model. They should be considered only when (a) there is significant harm done to others (e.g. bullying), and (b) those responsible are willing to apologise and make amends for their actions. What type of restorative justice process is then used will depend on the needs and wishes of all those involved. Many of the values (e.g. respect) and skills (e.g. active listening) that underpin restorative justice are shared by the other approaches; but it does not follow that they are the same process. Confusion on this point can (and has) led to serious consequences, including the suicide of a student who attended a ‘no-blame’ circle as a victim of bullying - with the bullies present (see web article). The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk An Overview of Restorative Justice in Scotland 2008 (Version 1.10 Text Only) 20 3.2 Best Practice Restorative Justice works best when the incident, the context and the participants are all suitable for a restorative justice approach. The following basic criteria are normally used to determine whether a case is suitable for restorative justice:* The incident has (or could have) caused harm to an identifiable individual(s). The relevant participants understand the nature and aims of the process, and are willing and able to participate on that basis. The process is likely to meet the needs and wishes of both the person(s) harmed and the person(s) responsible. The participants require the assistance of a third party and a structured process to resolve the matter. There is no significant risk to the well-being of any participant. * See the section on ‘Where is it used?’ for the specific referral criteria (‘Triggers’) currently used in various contexts. 3.3 Best Practice Restorative Justice works best when the process is facilitated in accordance with recognised best practice guidance. “Best Practice Guidance for Restorative Justice Practitioners” can be downloaded from: www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk/practitioners.htm 3.4 Effectiveness If the above apply, the process is more likely to achieve the aims of restorative justice. The following basic criteria* will determine whether or to what extent restorative justice has achieved its aims: The process has addressed or repaired the harm caused by the incident; The process has identified and contributed to the reduction of criminogenic need or other risk (and, to that extent, is likely to have thereby contributed to a reduction in re-offending or harmful behaviour); The process is not associated with an increase in re-offending or harmful behaviour. * See the section on ‘What can it do?’ for a more detailed list of criteria. Research papers on the effectiveness of restorative justice can be downloaded from this web page: www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk/research.htm The Scottish Restorative Justice Consultancy and Training Service, 2007 http://www.restorativejusticescotland.org.uk