Lecture notes 621 Psycholinguistics

advertisement

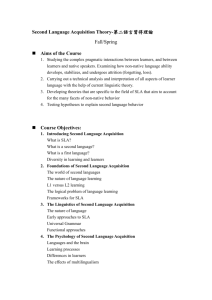

Week 2 (starts 9/19, ends 9/25): Introduction to First Language Learning This week we will briefly examine behaviorism and consider the milestones of first language acquisition. For this week, please -read O'Grady (2005), chapter 7 (in Additional Materials); -read Jackendoff, chapter 8 (a copy has been posted in Additional Materials since there was some mix-up with books); -read VP & W p. 17-25 (don't read the second part of the chapter on the Monitor Model); -consider the optional readings O'Grady (2005), chapters 2, 4, & 6 (in Additional materials); Lightbown & Spada (1999) (on e-reserves); Cook (1997) (on e-reserves); -contemplate the following questions as you read: 1. Define grammar. What is meant by child’s early grammar? 2. Define the following notions: lexicon and lexical development; morphology and morphological development; syntax and syntactic development; phonology and phonological development. Give an example for each aspect of child language development. 3. Name five striking observations in child language development. How do these observations contradict folk theory about child language development? 4. What kind of explanations does O’Grady present to explain child language development? -view the Week 2 lecture; -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 2 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (9/19), 10am EST. See you in class! Notes for Week 2 Jackendoff & O'Grady refer to first language acquisition (FLA) stages and developments. I've uploaded two additional files here that are relevant to this information. One is a more thorough account of the stages children go through (babbling, variegated babbling, one word stage, etc); the other is a chart summary of these stages. If you're interested in more details about FLA, you may find this information useful. Another file I've uploaded offers views on some additional theories of LA. I would encourage you to particularly read section 8.1.5 on the Active Construction of a Grammar theory (ACG). Our readings for week 2 discuss an "innate" ability to process grammar and a mental grammar that children have. What the readings don't discuss, however, is how this process actually takes place. The Active Construction of a Grammar theory offers an explanation of how children take the input they are given, process it, form hypotheses based on it, then try their own versions of output until they have enough input to "get it right." I highly encourage you to read more about ACG theory, especially as next week you'll encounter a lot of talk about "hypotheses," and this will be more easily understood through the ACG lens. You'll also find in that same document a section on Social Interaction theory. As many of you have noted, there's much overlap between sociolinguistics and psycholinguistics. Although our readings cover only the cognitive theories of LA (and these are more numerous) there are social theories of LA. The Social Interaction theory briefly presents this, as well as Schumann (1978), the Acculturation Model, which I've uploaded here. While our readings placed a heavy, heavy emphasis on the cognitive (and, some might say discounted the social), most contemporary psycholinguists actually believe that LA is enhanced and shaped by interaction (or the social); it's not just interaction between the linguistic environment and innately specified linguistic abilities (such as UG), but also the input that children receive from their care-takers and those around them. In fact, in one report, Genie was not successfully able to acquire language--she had no social interaction or exposure to input. See the uploaded article about Genie. (We will, in fact, explore sociocultural theories (including interaction) near the end of the course, so we'll return to these ideas later.) It's important to keep in mind that an eclectic approach to LA is always best. No one theory, as was noted by VP & W, can explain all observations of LA; aspects, however, can be better understood by appealing to numerous theories. Often thinking of the theories in terms of "strong" or "weak" is a good idea. For example, a "strong" version of contrastive analysis isn't valid; a "weak" version, however, can pinpoint certain phonological considerations (for languages with CV patterns only, for example). A "strong" version of reinforcement isn't valid; a "weak" version, however, does allow that children repeat certain words which elicit desired responses (for example, if you laugh at a particularly silly sound my 5-year-old makes, he'll make it 10 more times just to try to get you to laugh again). It's been said "beware the false dichotomy." This is so true. Again, an eclectic approach (a bit from here and a bit from there) is really the best way to account for LA. Week 3 (starts 9/26, ends 10/2): Milestones in Contemporary SLA Research This week we will examine types of data analysis, as well as discuss systematicity and interlanguage. For this week, please -read Larsen-Freeman & Long (1991), chapter 3 (p. 52-75) and chapter 4 (p. 88-96) (in Additional Materials > Required Readings); -read Bardovi-Harlig (1997) (on e-reserves); -read Corder (1967) (in Additional Materials > Required Readings); -read Tarone (1997) (in Additional Materials > Required Readings); -read Hamilton (2001) (on e-reserves); -consider the optional readings Long (2003) & Ortega (2009) (both in Additional Materials > Optional Readings); -contemplate the following questions as you read: 1. Define Contrastive Analysis and the Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (CAH). How do you relate the CAH to the Behaviorist approach of language learning? For which theoretical and empirical reasons was the CAH framework considered inadequate to understand second language learning? 2. What is meant by “order of acquisition” in L1 acquisition? How does Brown’s morpheme study support the order of acquisition theory? What is meant by “natural order of acquisition” and by “morpheme acquisition order” in SLA? 3. Define “developmental sequence.” Give an example. What do developmental sequences show about L2 acquisition? What are the implications for language teachers? How does recognizing developmental stages in learners’ interlanguage relate to evaluation? What beliefs might underlie the following statement? “All my students who are native Spanish speakers, say He no go instead of He doesn’t go. This is because negation is expressed that way in their native language.” 4. Define Interlanguage (IL). What are the main characteristics of learners’ interlanguage? How can we study our learners’ interlanguage? How can we take it into account in our teaching practice? 5. How was Corder’s insight into second language learners innovative? Consider quotes and arguments from Corder’s article to support your ideas. What was the major shift of paradigm that he brought up? 6. What are some examples of interlanguage variation? How has it been explained? 7. How has variability in interlanguage development been explained? Give examples. 8. Which criticisms have been raised against cognitive views on interlanguage development? 9. An example of interlanguage analysis: [From Hanania (1974)] A native speaker of Arabic at the early stages of learning English produced the following sentences. At the time of the data collection, she had not received any formal English instruction. All the sentences were gathered from spontaneous utterances (not in an experimental context). (Anything in parentheses refers to what the learner meant to say given the context when the intention is not obvious from the forms produced.) (1) He's sleeping. (2) She's sleeping. (3) It's raining. (4) He's eating. (5) Hani's sleeping. (6) The dog eating. (The dog is eating.) (7) Hani watch TV. (Hani is watching TV.) (8) Read the paper. (He is reading the paper.) (9) Watch TV. (He is watching TV.) (10) Drink the coffee. (He is drinking coffee.) What correct target language structures does this learner produce? What alternate forms does this learner use to express this structure? What may be the rules of her interlanguage system? What may explain her processing of the input? -read the Notes for Week 3; -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 3 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (9/26), 10am EST. -begin to consider the Practice Essay assignment. See you in class! Notes for Week 3 Hopefully you were able to read about ACG last week, as an understanding of how the hypothesis process works is helpful for processing much of this week’s reading relating to errors. As some of you noted in the discussion for week 2, there are many valid constructs for ACG. Though structural/descriptive linguistics has “gotten a bad rap” being associated with behaviorism and inspiring a strong view of contrastive analysis, as Bardovi-Harlig (1997) notes there is a role for a description of language, particularly in relation to materials development. Fries (1945, as cited in Larsen-Freeman & Long, 1991, p. 52) got it half right when he said “The most efficient materials are those that are based upon a scientific description of the language to be learned…”. Corpus linguistics describes language as it is actually used, and this can lead to more efficient language learning (or study of interlanguage, as you’ll see in a moment). I’ve uploaded a chapter here (Bennett, 2010) which provides an overview of corpus linguistics just to give you an idea of the relevance of description (since we’ve only looked at it as “bad” so far. It’s really just through page 14 that is directly relevant here, but I’ve provided the whole chapter). Sylvenie Granger has done a lot of work in corpus linguistics specifically investigating interlanguage. Both articles uploaded here by Granger as well as the article by Pravec specifically detail the use of learner corpora and their use in studying and understanding learners’ interlanguage. The last article (Seville & Hawkey) provides an overview of another descriptive project relating to language learning and language learners’ levels, The English Profile Project. All of these are practical applications of work based on an interlanguage theory. Tarone and Larsen-Freeman & Long mention the influence of task on interlanguage (especially in relation to linguistic versus situational influences). Watch the posted video for a great explanation by McCarthy (one of the leaders in the Profile Project) about analyzing learner data and considering the influence of task! Last week I discussed an eclectic approach to SLA as a means of best practice. That view is again espoused in this week’s readings; as Larsen-Freeman and Long (LF-L) note, each of the theories discussed in Chapter 3 builds on one another. We’ll see later (and as I offered a look at some social SLA theories last week), and as proposed by Tarone (1997) and Hamilton (2001), a social perspective combined with the cognitive approach continues to build one theory to another. Accounting not only for the cognitive/logical elements of language, but also considering those at work in social settings and how affect plays in language (and language learning) is a more complete view. As Tarone (1997) emphasizes, SLA is cognitive and social (p. 137); social processes affect cognition (p. 144); and SLA theories can and should relate cognitive and social (p. 141). Although he doesn’t do it as nicely, Hamilton (2001) is making the same arguments as Tarone, namely that the “cognitivist version” doesn’t account for setting, purpose, or affect. (Surprisingly, Hamilton does not account for the complexities of pragmatics.) And while neither Tarone nor Hamilton acknowledge that Corder (1967, p. 81) does mention “only the situational context could show whether his utterance was an error or not,” their concern for more social theories merged with cognitive ones for a complete SLA theory is valid. One important social theorist mentioned is Vygotsky; he’s important in the social constructivist movement and to the social perspective for SLA; keep him in mind. However, if we go back to VP & W (2007, p. 9-12) and the “least” which must be accounted for in a theory of SLA, where do social aspects fit into these observations? Are they really necessary? While you can reach an answer to the first question on your own, I’ll offer that “Yes,” is the answer to the second question. (In week 12 we will examine more sociocultural perspectives on second language learning.) Week 4 (starts 10/3, ends 10/9): The Role of the Native Language This week we will look more specifically at the role of L1, especially in terms of how and when SLA is effected, including the theories of markedness, perceived transferability, and multicompetence. For this week, please -read Larsen-Freeman & Long (1991), chapter 4 (p. 96-108) [in Additional Materials > Required Reading (/Viewing)]; -read Gass & Selinker (2008) [in Additional Materials > Required Reading (/Viewing)]; -read Kellerman (1985) (on e-reserves); -read Cook (2010) [in Additional Materials > Required Reading (/Viewing)]; -view the link "Multicompetence--the Home Movie Reel 1" [in Additional Materials > Required Reading (/Viewing)]; -view the link "The L2 Language User--The Home Movie Reel 2" [(in Additional Materials > Required Reading (/Viewing)]; -consider the optional reading Ortega (2009) (in Additional Materials > Optional Reading); -contemplate the following questions as you read: 1. How does L1 influence interlanguage and developmental sequences? How does transfer operate in tandem with natural developmental principles in determining the ways interlanguages progress? 2. According to Eckman's Markedness Differential Hypothesis, in which cases will L1 have an effect on second language acquisition? What are some examples that may be used as evidence against the claim that differences between L1 and L2 cause difficulties in SLA? 3. What is "U-shaped behavior"? What are examples of this phenomenon? Why does Karmiloff-Smith describe learners as "going beyond success"? How does U-shaped behavior relate to the discussion of cross-linguistic influence? -read the Notes for Week 4; -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 4 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (10/3), 10am EST. -continue to consider the Practice Essay assignment; -complete the Doodle Poll to schedule our Wimba 1 session. See you in class! Notes for Week 4 Researchers concluded that the initial yes/no question “Does L1 affect SLA?” was too narrow to accurately reflect the role of the native language in SLA, and so the question evolved to “How and when does L1 affect SLA?” with researchers focusing on how (delaying, extending, or quickening time in developmental sequences or adding sub-stages) and when (when structures are marked or salient, or learners perceive them to be). Cook (2010) posits, however, that even this question is too narrow to truly reflect the relationship between L1 and L2s. According to the multi-competence framework, the question is “In what ways does having knowledge of more than one language impact an individual?” This question has yet to be fully explored (like most elements of SLA), but we know that not only is transfer involved in SLA, but that L2 can influence use of L1 as well as an individual’s overall worldview! Thus, the latest research on L1 and SLA (multi-competence) suggests “not only new interpretations of existing theories and phenomena but also new research questions” (Cook, 2010, final ¶) to expand our understanding of the relationship between language and language user. The evolution of the “transfer question” from behaviorist, to cognitive, to learner demonstrates the importance, again, of an eclectic approach which pulls “weak” versions of all theories together, accounting for multiple perspectives and building on previous ideas. Research into identity in language learning and use is one larger aspect which has emerged from a more holistic approach to the learner in SLA. Lives in Two Languages is a good starting point if you'd like to explore more about identity in SLA. The idea of “chunks” has appeared often in our readings over the past several weeks (Atkinson, 2011; Gass & Selinker, 2008; Larsen-Freeman & Long, 1991; Kellerman, 1985) and will appear again (though in each instance it is merely a referral to such chunks and never a focus on them). I’ve uploaded an article here (Wood, 2002) which introduces and reviews the research on chunks (or multi-word expressions, lexical phrases, chains, among other terms) and their relevance to SLA (which has been discovered namely through the work of corpus linguistics). It’s important to keep this idea of the facilitative nature of phrases (and their contribution to proficient-like language use) in mind as we continue to read about UG and systemic language. One last word on transfer. Pedagogically speaking, strictly in terms of L1àL2 use, access to various research which presents differences between certain L1s and English has been proposed as a springboard on which to pinpoint targeted areas of instruction. Consider the list of grammatical and phonetic differences between English and various L1 presented in the document Transfer Skill Notes as well as the information contained in the two books linked here. Is this information useful as an instructor? To what extent? How can this information be viewed through a multi-competence framework? Week 5 (starts 10/10, ends 10/16): The Universal Grammar Approach to Language Learning This week we will begin our exploration of Chomsky’s Universal Grammar (which we’ve already heard so much about); specifically we’ll examine principles and parameters of the theory, how it relates to language acquisition, arguments and evidence for an innate knowledge of grammar, and the Poverty of the Stimulus Argument. For this week, please -read Cook & Newson (2007), chapter 1 (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -read Cook & Newson (2007), chapter 2 (p. 45-60 only) (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -read Cook & Newson (2007), chapter 5 (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -read Jackendoff (1994), chapters 2-3; -read Jackendoff (1994), chapters 6-10; -consider the optional readings Cook & Newson (2007, p. 28-45); Balter (2009); Chomsky (1967) (all in Additional Materials > Optional Reading); Baker (2001, chapters 1-4) (recommended book); Van Patten & Williams (2007, chapter 3); -contemplate the following questions as you read: 1. How does Chomsky define language? What are the goals of linguistic theory? What is Chomsky’s research program? Why does syntax play a central role according to Chomsky? 2. Explain what is meant by “logical problem of language learning,” “Paradox of language learning,” and Poverty of the Stimulus? How does Chomsky address the logical problem of language learning? 3. How is Universal Grammar defined by Chomsky and Jackendoff ? What is mental grammar? What is the difference between universal grammar and mental grammar? 4. What is a phrase? What does it mean to say that language has a hierarchical structure and not a linear one? What is Structural Dependency? 5. Define “principles,” and “parameters.” How are principles and parameters related to Universal Grammar and mental grammar? Give an example of principle and parameter and explain how it is supposed to ease child language acquisition. 6. According to Chomsky and universalists, what do children have to do to learn their first language? 7. List the various sources of empirical evidence (observable facts) presented by Jackendoff that led scholars to posit a biological basis for language knowledge. Which of these observations have led scholars (Chomsky in particular) to argue that there is an innate faculty specific for language learning? -read the Notes for Week 5; -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 5 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (10/10), 10am EST. -continue to work on the Practice Essay assignment. See you in class! Etienne, Apling 621 1 APLING 621 The Universal Grammar Approach - Chomsky 1. Key Issues Poverty of the stimulus; innate principles; LAD; principles and parameters; lexical and functional categories; clustering of properties; linguistic competence, linguistic performance. When children start to speak, their cognitive development cannot account for the level of abstractness necessary to master language rules (¡§Logical Problem of Language Learning¡¨ or Plato¡¦s problem: how can children know so much when they have never been taught? Where does their knowledge come from?) Poverty of the Stimulus: The stimulus is poor because it is limited, flawed by performance factors (false starts, random errors, distractions, shifts of attention, memory limitations, etc.), and deprived of negative evidence. The input to the child from her caregivers consists of sample sentences. From these sentences, the child must deduce the rules of her grammar. If the child does not make the proper generalization, he will not be able to generate all rules of his/her language. The input does not tell the child exactly what the correct hypotheses are. In other words, the ¡§stimulus¡¨ (input) is too poor to provide all the information the child ends up knowing. Chomsky argues that while children are presented with lots of information on possible grammatical sentences, they are not presented with information on impossible sentences (children don¡¦t receive negative evidence) and so would be unable to rule out incorrect hypotheses making it impossible for them to discover the actual grammar of their language in such a short period of time SVO ¡V He ate the cake. OVS ¡V The cake was eaten by him *VOS ¡V Ate the cake by him/he *VSO ¡V Ate he the cake *SOV ¡V He the cake ate How could the child come to know that the last three examples (above) are unacceptable utterances in English, unless some aspects of the child¡¦s knowledge was innate? Example: He always plays football Let us suppose that one child encounters this sentence in her input. According to Chomsky¡¦s model, how does she make sense of it? What does she get from this input? Etienne, Apling 621 2 Because she is equipped with universal principles, she is able to map out the structure of the sentence. Before being exposed to language, among other things (I am not referring here to the phonological knowledge she also has), she knows that: ¡E all languages have phrases (lexical ones and functional ones): groupings of words that form higher level structures on which language rules operate. ¡E functional phrases are determiner; agreement, inflection phrases, etc. ¡E sentences consist at least of a noun phrase NP and a verb phrase VP ¡E every phrase has a head and a complement and may have a specifier (SPEC) ¡E complements may follow or precede the head; specifiers may follow or precede the head + complement grouping (called X¡¦) ¡E the properties of functional categories may vary across languages but this variation is limited to a small set of possible values (¡§parametrized¡¨) So being exposed to the sentence above, she¡¦ll be exposed to some lexical items such as ¡§play, he, football ¡¨ She¡¦ ll find out that English is a head-first language just by seeing the verb phrase (¡§plays football¡¨). She will notice that the verb does not raise to the INFL phrase to collect its inflection and thus know that INFL (inflection) is weak in English. All these observations based on one single sentence will give this child instant knowledge about many other characteristics of English. For instance, she will know that she can¡¦t say ¡§ He plays always football*,¡¨ that any determiner precedes the noun, that the noun precedes its complement, that there are prepositions in English, etc. In other words, by being exposed to very limited input (one sentence), the child will be able to set many parameters (that before being exposed were potential rules) and learn a whole cluster of properties about that language. If the child did not have this previous knowledge (UG), there would be no way she could know just by seeing ¡§He always plays football¡¨ that ¡§he plays always football¡¨ is impossible. 2. View of Language ¡E A system of mental representations: competence that enables any speaker to understand and produce infinity of novel utterances in spite of performance factors. ¡E A very abstract and complex system of rules that can account for the production and understanding of an infinite number of sentences. These rules are syntactical in nature, similar to mathematical formula in a way. ¡E ¡§a computational procedure which is virtually invariant across languages and, a lexicon¡¨ (Chomsky, 2000, p. 120). In order to learn the settings of the parameters applying to a given language, you need to be exposed to its lexicon. 3. Source of Knowledge and Role of Environment Language Learning Faculty (LAD) -> UG + lexicon Etienne, Apling 621 3 UG: Invariant universal principles (example: structure dependency) + parameters (example: head parameter). Parameters are universal rules that may slightly vary from language to language. Parameters will be set by any encounter with the functional categories contained in the lexicon. The parameters are the source of cross-linguistic variation (differences between languages). Principles and parameters control the shape human languages (including interlanguages) can take (Mitchell & Myles, p. 54) Input (or stimulus): very limited exposure necessary to set up the parameters. The setting of one parameter entails the mastery of several structures that may be superficially unrelated (clustering of properties). Input will also help children acquire lower-level rules or language specific rules that play a minor rule and vocabulary/lexicon. 4. Development Process Short; ¡§language happens to children.¡¨ Superficially unrelated properties of language are suddenly acquired by the child (clustering). The development process is uniform across children. Chomsky is not interested in performance data because they do not reflect children¡¦s internal knowledge about language. 5. Learner¡¦s role Passive: the child learns to speak as he learns to walk. S/he is programmed to do so. 6. Educational Implications Chomsky did not write about possible teaching implications but his proposal has considerably influenced research in second language acquisition: ¡E Language learning does not result from habit formation but from a creative process ¡E Discussion about the role of innate principles in second language acquisition ¡E Concept of interlanguage, developmental sequences, orders of acquisition, etc. ¡E Error analysis ¡E Approaches such as the Natural Approach where second languages are believed to be learnt the same way first languages are learned ¡E New role of the teacher ¡E Learners are in charge of their own learning (grammar will emerge by itself) ¡E Theory of markedness to explain cross-linguistic influence Etienne, Apling 621 4 ¡E All human languages and dialects are ¡§equal, ¡¨ (equally systematic) governed by the same universal rules. Interlanguage is believed to be a natural language following the principles of UG. 7. UG and Second Language Acquisition (SLA) First language acquisition and SLA have many similarities (progression through stages observed in children acquiring their L1 and in adults acquiring their L2 regardless of their L1 background; these stages are unlike L1 or L2) -„³ Some part of LAD should still be active; part of UG should be accessible BUT The initial knowledge base is very different: ¡E Children are not cognitively mature; adults are. ¡E Motivation does not play any role in L1 learning; it does in SLA ¡E Adults already have a language and thus know what to expect from a language (they have some assumptions) It is not any more a question of access or no access but rather about the availability of submodules of UG NO access: ¡E IL grammars are wild Or ¡E Il grammars are target language like but this is not achieved through UG (cf: Meisel and structural dependency principle) Full Access ¡E Full access; no transfer (cf: Flynn) : parameters can be reset ¡E Full access; full transfer initially; then resetting of parameters ¡E Full access; impaired initial representions; then resetting Partial Access ¡E Access to principles; no parameter resetting; knowledge base: L1 and general problem-solving strategies (cf: Bley Vroman; Schachter and the windows of opportunity) ¡E Access to principles; impaired functional features 8. Evaluation of UG Approach Strengths of UG driven approaches to SLA: . provides a framework for describing and comparing languages (L1, L2, Interlanguages) and defining what is to be learned . explains some of the facts of SLA Etienne, Apling 621 5 . attempts at testing empirically very specific facts. Weaknesses of UG driven approaches to SLA: . Language acquisition does not take place as fast as Chomskians think it does (some rules are acquired late and without negative evidence) . some syntactic principles traditionally believed to be innate have been shown to be learnable. Example: the structure-dependence principle *Is the man, who happy, is at home? According to Parker (1989), the learner only needs to make conservative hypotheses (inversion is possible only in main clauses as shown by positive evidence) and to be able to distinguish main clauses from embedded clauses. . Some of the transitional structures in developmental sequences are not predicted by UG . Positing access to UG cannot explain why adult learners go through various, specific stages on the way of acquiring a given structure. White (1981) suggests that the whole of UG is available to the child from the start but that there is an interaction between the universal principles and the child¡¦s developing perceptual abilities. . When researchers try to show that the acquisition of one structure triggers the acquisition of others, the triggering effect is never immediate but progressive. Then, what is the percentage of accuracy or of use of a specific structure that may be required to decide that a parameter has been reset? One example is the resetting of the Prodrop parameter in acquisition of English by a Spanish speaker (Hilles, 1979). The appearance of expletives (¡§it¡¨; ¡§there¡¨) coincided with a marked decline in the frequency of pro-drop (from 20% to 65%). . There is disagreement on what is the unmarked setting of a parameter (prodrop parameter). For instance Chomsky (1981b) believes the pro-drop parameter is initially set neutrally whereas Hyams (1983) assumes +pro-drop as the initial (unmarked) setting and White (1984) sees pro-drop as the marked form. There is also a danger of circularity: an unmarked parameter is one that is fixed early while a parameter that is fixed early is unmarked. . UG approaches are based on a theory of language rather than on a theory of language learning (target-language orientation) . Social and psychological variables in SLA ignored . Methodological difficulty in accessing L2 learners¡¦ intuitions Etienne, Apling 621 Understanding Chomsky’s Proposal If the child knows how to interpret and produce very complex linguistic structures in advance of experience, without instruction, without proceeding through trial and error (he would be unable to do that anyway because his cognitive abilities and general learning mechanisms are not fully developed yet), he has innate linguistic knowledge: he comes to the world with some knowledge, not as a “blank slate” (tabula rasa). This knowledge is contained in the brain/mind, as a specific language faculty or language acquisition device. Nothing can prevent a child to learn to walk at a certain stage in his biological development without any instruction. Similarly, all children start speaking unless they are submitted to very unusual circumstances. The language faculty is common to all human beings: it is a species-specific property. Then how can Chomsky explain that there are so many different languages? What does the language acquisition device (LAD) in the brain/mind consist of? The LAD contains a universal grammar (UG) that native speakers use to construct the mental grammar of their language once they are exposed to some input. The LAD has a way of distinguishing particular groups of words from others, although it does not call them noun phrases, verb phrases, etc. It has a way of stating relations between various parts of a sentence although it does not call these relations “binding theory, asymmetry principles,” etc. Chomsky knows about the reality of native speakers’ mental grammar because he observes the judgments of grammaticality and meaning that native speakers produce by using this mental grammar (Jackendoff, p. 45-46). UG contains: 1. Invariant universal principles that all human beings, regardless of their language environments, possess at birth. Human beings apply these principles to any language they are acquiring. Examples: - Principle for forming causative and other embedded constructions - Structural dependency: “Linguistic rules operate on expressions that are assigned a certain structure in terms of a hierarchy of phrases of various types.” (Chomsky, 1988, p. 45). For each choice of X (V, N, A, P) there is a phrase XP (VP, NP, AP, PP) with the lexical category as its head and the phrase YP as its complement - Principle of asymmetry: The subject and the verb are in separate phrases, but the verb and the object form a single phrase. - Binding theory (connections between pronouns and their referents or antecedents: Pronouns come in two forms, free pronouns and bound pronouns; a pronoun must be free in its domain). 2. Variant rules/parametrized rules/parameters: rules that may vary, within certain limits, from one language to another. One parameter may have the same Etienne, Apling 621 value in several languages. Values of parameters have to be set or defined by exposure to the linguistic environment, in particular to the lexicon and its functional categories (phrases headed by functional words such as determiners, tense or gender features, etc.) Examples: - Order of the head and complement in phrases (English is head-first; Japanese is head last) - In embedded constructions, position of the subject (In English it precedes the verb; in Spanish it follows the verb) - Pro-drop parameter or null-subject parameter; in some languages (Spanish, Arabic, and Italian for example) the subject of declarative sentences may be deleted What does Chomsky want to do when he looks at linguistic examples and finds out principles and rules such as the projection principle, the asymmetry principle, the binding theory, anaphors, etc. ? (1) Sue washed herself. (2) Sue believes that the men like herself. * (3) The children want Joe to entertain themselves * Sentences (2) and (3) are ungrammatical: They do not receive any interpretation from native speakers. Chomsky tries to formulate a rule that represents what might take place in the minds of native speakers who intuitively know that (2) and (3) do not mean anything. This rule must also account for the fact that (1) is fine. He posits principles and defines concepts such as anaphors, Binding Theory, etc. These concepts are "crutches" for us to understand an unconscious mechanism consciously. In the case of (1), (2), and (3), Chomsky explains native speakers’ judgments by defining the concept of anaphor: an NP that must have an antecedent (a referent) in order for the sentence containing it to be grammatical. An anaphor cannot refer directly to something in the real world but depends on its antecedent for reference. (2) and (3) are ungrammatical (cannot be interpreted) because the antecedent is too far away from the anaphor. So there must be an unconscious rule that determines how close an anaphor must be to its antecedent. Chomsky examines possible and impossible language productions such as (2) and (3). He asks for grammatical judgments from native speakers. In other words, he taps on the knowledge of native speakers (competence). Then he tries to formulate some rules that can explain why native speakers reject sentences like (2) and (3) and accepts (1). The rules he formulates (binding theory) are complex. Rule 1: An anaphor is bound in the minimal domain of a subject. Rule 2: A pronoun is free in the minimal domain of a subject. The domain is the smallest phrase where a constituent is. Etienne, Apling 621 All along, Chomsky’s goal is to show how the child's feat is possible, that is to say the logic of the child's language growth and maturation. Chomsky’s goal is to show how the learned component of language is reduced to the lexicon and to the choice of values for a limited number of parameters Chomsky greatly contributes to the description of human languages. He points out that what seems to be obvious to all speakers is in fact very complex. To him, there is a failure to perceive what is involved in the growth and use of language. Through all the examples presented, he shows that the interpretation or production of sentences and current linguistic operations (embedded clauses, use of pronouns, question formation) involve complex abstract processes that are unconscious. For all examples, he shows that there is more than meets the eye; that the human language system cannot be described focusing only on the segmentation and description of the pronounced structures. Week 6 (starts 10/17, ends 10/23): The Universal Grammar Approach (2)This week we will continue our exploration of Chomsky’s Universal Grammar. For this week, please -read Cook & Newson (2007), chapter 6 (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -consider the optional readings from week 5 (if you haven’t already): Cook & Newson (2007, p. 28-45); Balter (2009); Chomsky (1967) (all in Additional Materials > Optional Reading); Baker (2001, chapters 1-4) (recommended book); Van Patten & Williams (2007, chapter 3); -contemplate the following questions while you read: 1. What arguments and evidence can support a view of SLA based on partial UG access? 2. Does the poverty of the stimulus argument applies to SLA? 3. How would you test UG access in SLA? What groups of learners would you consider? On which aspects of language would you focus? What tasks would you use? What do you need to demonstrate if you claim UG access in SLA? 4. What are the 3 logical possibilities (hypotheses) concerning the role of UG in L2 learning? a. What empirical support is provided for each of these hypotheses? b. What is the role of the critical period in these hypotheses? 5. What is the main criticism opposed to UG theorists in SLA? What aspects of SLA can a UGbased approach not explain? -read the Notes for Week 6; -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 6 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (10/17), 10am EST. -submit the Practice Essay assignment (located in Week 6 materials). See you in class! Notes for Week 6 In UG, principles apply to all languages and are “universal.” All languages have parameters (or Jackendoff’s term “Mental Grammar”), but parameters are language specific. Different languages have different parameters, and this is what distinguishes them from one another. According to Cook & Newson (2007, p. 222), Chomsky, however, views parameter settings as different not only from language to language, but also from register, dialect, or variation within a language. In this sense, he believes that everyone is “multilingual” and holds more than one grammar in their mind. (It’s almost as if he doesn’t really understand what it means to really know another language!) In fact, he subscribes to the interlanguage (IL) and ACG (active construction of a grammar) theories, as he declares that during the transitional period in first language acquisition( FLA) children have two parameter settings in their mind simultaneously (p. 223). The road from L1 initial state to L1 final state (depicted in figure 6.4, p. 230) is filled with intermediate states (the interlanguages). Thus, according to Chomsky, each person is multilingual in that during the development of L1, multiple grammars (the ILs) exist (and since everyone is “multilingual”) the purity argument stands. However, following the tenets of multiculturalism studied in week 4, Cook and Newson (2007), of course, argue that it is actually the working knowledge of more than one language which is the norm, and the purity argument is invalid in that every person has the capability to become multilingual. As such, UG must be approached from the multilingual mind. In the discussion of “the states metaphor,” we see IL again (as well as transfer; what we’ve learned previously in this course about both these ideas is necessary to understand and evaluate the states metaphor). Figure 6.9 (p. 238) offers a clear look at the alternative hypotheses of the initial second language state. Given what we know about transfer in SLA, the “Full access” and Partial access “minimal trees” and “valueless features” hypotheses must not be valid because they discount any influence of L1. For Cook and Newson, the “no UG access” and partial access “failed functional features” hypotheses can neither be valid because they do not presume any role of UG in SLA. This leaves the “Full transfer/full access” hypothesis where both L1 and UG serve as the initial state for L2. Cook and Newson (p. 238) note that “the L2 learner’s grammar is still a possible human language within the remit of UG principles and parameters but different from either the L1” or the target L2 (application of IL), and thus “UG is still available in L2 acquisition.” Two points to keep in mind when considering the arguments related to the states metaphor. Firstly, while the final state mental grammar may be developed for L1, our pragmatic competence (knowledge of vocabulary, even grammar, writing skills, etc) is never really terminal, even in the L1. We may always be adding L1 knowledge, and thus it isn’t necessarily a “terminal L1” that serves as initial state for L2, because it may develop along with the L2; it is a “developed L1” (and one that can be improved). This also falls in line with what Cook demonstrates through multi-competence research (e.g. that L2 can influence L1). Secondly, we know that FLA necessitates social interaction (for input as well as practice [to formulate and perfect hypotheses (ACG)]). All anecdotal evidence for SLA also points to the necessity of social interaction for the more terminal knowledge of the L2. When learners are in an “immersion” environment (with lots of input and opportunity to construct and develop hypotheses), “native-like” proficiency is much more likely. Week 7 (starts 10/24, ends 10/30): Emergentist Approaches This week we will look at alternative approaches to language (i.e. those in opposition to UG); specifically we’ll examine “emergentist” approaches which purport that the complexity of language must be understood in terms of the interaction of simpler and more basic non-linguistic factors, such as human physiology, the nature of perceptual mechanisms, the effect of pragmatic principles, the role of social interaction in communication, the character of learning mechanisms, and limitations on working memory and processing capacity. For this week, please -read Van Patten & Williams, chapter 5; -read Gass & Selinker (2008), chapter 8 (p. 219-226 only) (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -read MacWhinney (2001) (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -consider the optional readings Ellis (2003) (in e-reserves) and MacWhinney’s Home Page (linked in Additional Materials > Optional Reading). -read the Notes for Week 7; -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 7 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (10/24), 10am EST; -study for the Mid-term exam next week (study guide in Additional Materials > Lecture). See you in class! Notes for Week 7 There is no one emergentist approach to language, and theories which are labeled as emergent have their distinctive features; nevertheless, emergentist approaches are characterized by 5 criteria. Emergentist approaches believe that 1. linguistic and non-linguistic factors (nature and nurture; behavior and cognition) account for acquisition; 2. neural connections (interaction) among the brain, input, and context account for acquisition; 3. there is only one process involved in learning (language or otherwise; i.e. there is no special “language learning” process); 4. performance and frequency matter in acquisition; 5. comprehension and production are involved in language acquisition. frequency + rational processing (probability and prediction) + context = language comprehension and use Perhaps the most distinguishing feature of emergentist approaches is that they are in opposition to UG. Table 1 provides an overview of UG versus emergentism. While emergentist approaches are against the idea of innate linguistic structures, they do, interestingly, acknowledge the role of a “device” in acquisition. It isn’t a “language acquisition device,” but rather is described as a “detector unit” that fires in the presence of a word or structure (thereby making the neural connections). Table 1. UG v Emergentism UG Emergentism Generative grammar Construct grammar Theoretical Applied (usage-based) Generative learning Emergent learning Parameter resettings Learned attention Innate structures Neural connections LAD detector firing unit One tenet of emergentist approaches is that language acquisition is a complex adaptive system— it is the interaction of properties (perceptions, cognition, motor, social) which lead to acquisition, and no one factor is sufficient to account for acquisition. Ellis describes “SLA as a dynamic process in which regularities and system emerge from the interaction of people, their conscious selves, and their brains, using language in their societies, cultures, and world” (p. 85). Because emergentism accounts for more factors—the learner, input, context, social interaction, etc.—it is not surprising that all 10 of the observations which need to be explained by theories in SLA (VP & W, p. 9-12) are addressed in these approaches. Emergentist approaches also provide an explanation for why people don’t succeed in SLA— learned attention; the idea that “as a result of early years of development, experience, and socialization, the brain’s neurons are tuned and committed to the L1” (p. 234). MacWhinney uses the term “plasticity” and the difficulty involved in creating a completely new set of connections. L1 learned attention limits the amount of intake from L2 input, thus restricting St (the endstate) of SLA. Specifically distinct from UG, of course, are emergentist approaches’ acknowledgment of performance, frequency, and saliency. The importance of these factors leads to pedagogical applications which focus on implicit learning and noticing and attention. One important note here, though: Gass and Selinker explain that “connectionist systems rely not on rule systems but on pattern associations” (p. 220) derived from frequency. The underlying assumption here is that rule systems and pattern associations derived from frequency are separate ideas; in fact, they are not mutually exclusive; pattern associations can, in fact, create neural connections which can then be viewed as ‘rule systems’ (such as learned attention). Very similar ideas, different terms and approaches; don’t let the seeming “opposition” of various approaches cloud the similarities present! Missing from emergentist approaches is a convincing explanation of the “logical problem.” Ellis (p. 88-89) does attempt to address the logical problem through the idea of the prototype, but this doesn’t physically explain how neural connections are made for something that hasn’t been encountered. As far as the logical problem, emergentist approaches are nearly as theoretical as UG. Evidence for emergentist approaches from the Competition Model (numerous discussed in MacWhinney, 2001; though note most of these focus solely on agent and no other grammatical aspects) and DeKeyser (1997) and Robinson (1997). Apling 621 Psycholinguistics Midterm Exam Study Guide You should be able to define and discuss the following concepts and/or issues: • Milestones of child language development: striking characteristics of this development and attempts of explanations. • Factors contributing to the development of a “good” theory; role of a theory of language acquisition. • Relevance of psycholinguistics to language learning and teaching: To what extent can it help language teachers to think about the learning process? In what areas can it be helpful? • Behaviorist position: stimulus-response-reinforcement; role of imitation and transfer. • The Universal Grammar (UG) Approach: Chomsky’s L1 acquisition model o Logical problem of language learning; Paradox of language learning; o Poverty of Stimulus argument and other arguments for innate structures; o LAD: principles and parameters—examples, why and how they facilitate language acquisition; o Chomsky’s view of language and research goals; o how the milestones of first language acquisition are accounted for. • How research on UG has been applied to second language acquisition (goals of research, hypotheses, types of data, pros and cons). • SLA Research Findings o Interlanguage: definition, development, learner variation, different ways of looking at and analyzing IL, strengths and limitations, classroom implications; o developmental sequences: definition, contribution to SLA understanding, teaching implications; o Acquisition Order: morpheme studies, what they show, associated problems; o data analysis: definition of Error Analysis, Performance Analysis, Discourse analysis; strengths and limitations; how each of modes of analysis contributes to an understanding of SLA. • Cross-linguistic influence on SLA: definition; considerations of how, when, and why CLI; beyond CAH. • For any given perspective on language learning, the following components according to that perspective: o Goals and rationale; o View of language; o Source of knowledge; o Key terms and issues; o Role of environment, role of learner, role of social interaction, type of language data considered relevant; o How learning happens; o Arguments and empirical evidence; o Examples of studies conducted within that perspective; o Strengths and limitations; o Implications for teaching. You should be able to address any specific question related to the above material. That does not mean writing everything you know about a given issue but rather relating your knowledge of the issue to a specific question about it. You should be able to precisely define the terms you use. All the practice essay questions (or any variants on them) could be exam questions. Week 8 (starts 10/31, ends 11/6): Mid-Term This week we will have our Wimba 1 session in preparation for the mid-term exam; we will also complete the mid-term exam. -The Wimba 1 session will be held at 8:00pm, October 31, in the Wimba classroom. The classroom (backpack) is linked here under Week 8. Talk to you there! -The mid-term exam will be open Friday, November 4, midnight (EST) to Sunday, November 6, midnight (EST) (this means you will have all day Saturday and all day Sunday to complete the exam). It will be linked here under Week 8. Once you open the exam, you will have three hours to complete it. (More details at the Wimba 1 session.) Week 9 (starts 11/7, ends 11/13): Pienemann’s Processability Theory This week we will continue looking at alternative approaches to language (i.e. those in opposition to UG), specifically examining information processing theories. For this week, please -read Van Patten & Williams, chapter 8; -read Gass & Selinker (2008), chapter 8 (p. 226-241 only) (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -consider the optional reading Larsen-Freeman & Long (1991), p. 270-287 (this section describes an older version of Pienemann’s Model but gives additional information on the Processability Theory) (in Additional Materials > Optional Reading). -contemplate the following questions as you read: 1. What is the main cognitive challenge for second language learners according to Pienemann? 2. What is the “language processor?” What does it mean to say that “language is constrained by processability”? 3. How does Pienemann explain developmental stages in SLA? How does Pienemann’s work on developmental sequences differ from what we have read so far on this topic? Give some examples from the acquisition of English?. 4. How does Pienemann explain the intermediate forms of interlanguage and interlanguage variability? 5. To what extent could we say that Pienemann’s model could help elucidate Krashen’s notion of i+1? What are the teaching implications of the Model? 6. List the differences and similarities between Chomskian SLA models and Pienemann’s view on language acquisition. Think of the research goals, the data used as evidence, the role of innate mechanisms, the learner’s contribution, and the role of the environment. -read the Notes for Week 9; -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 9 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (11/7), 10am EST. See you in class! Week 10 (starts 11/14, ends 11/20): Input and Interaction in Second Language Learning This week we will discuss empirical studies linking interaction and acquisition, examine the role of feedback in SLA, and review Krashen’s Monaitor Model and Input Hypothesis, Long’s Interaction Hypothesis, and Swain’s Output Hypothesis. For this week, please -read Van Patten & Williams, chapters 2 (p. 25-35 only) and 10; -read Gass & Varonis (1994) (on E-Reserves); -read Polio & Gass (1998) (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -read Mackey, Gass, & McDonough (2000) (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -read Philp (2003) (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -contemplate the following as you read: 1. Summarize the main tenets of Krashen’s Monitor Model and the criticisms that have been raised against it. What are the necessary and sufficient conditions for language development to occur? 2. What are the research goals of Interactionists or Interaction Researchers? a. Formulate Long’s Interaction Hypothesis. b. What research questions does it pose? c. Define negotiation of meaning. How can it happen in language learning? Why might it be useful to interlanguage development? d. What kind of methodology do Interaction researchers adopt? 3. What is Swain’s Output Hypothesis? Why is it an Interactionist hypothesis? 4. Define positive and negative evidence. Why are recasts of interest to Interactionists? 5. What are Language Related Episodes (LREs)? Why are they of interest to Interactionists? To what extent are they relevant to Swain’s Output Hypothesis? 6. How do Interactionists or Interaction Researchers build on Krashen’s definition of CI and move beyond it? Which questions are they asking about input? -read the Notes for Week 10; -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 10 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (11/7), 10am EST. See you in class! Week 12 (starts 11/28, ends 12/4): Sociocultural Perspectives on Second Language Learning This week we will discuss sociocultural theories of SLA, including the concepts of scaffolding, the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), and the definition and role in development of private speech. For this week, please -readVan Patten & Williams, chapter 11; -readSwain (2000; 2007) (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -read Nassaji & Swain (2001) (in Additional Materials > Required Reading); -read Kinginger (2001) (on e-reserves); -read Donato (1994) (on e-reserves); -consider the optional readings by Vygotsky (on e-reserves) as well as additional information on and by Vygotsky (in Additional Materials > Optional Reading). -contemplate the following as you read: 1. What does Swain mean by collaborative dialogue? How different is it from the view of interaction we have read about in the previous week? 2. What is meant by “symbolic tools or higher-level cultural tools” and “mediation”? What is the innate part of psychological processes for Vygotsky? 3. What is the relationship of language to symbolic tools and mediation of mental activities? What is meant by object-regulation, other-regulation, and self-regulation? 4. How is Vygotsky’s proposal different from Behaviorism? What is the role of imitation in Socio-Cultural Theory (SCT)? 5. What is the function of private speech? How is private speech different from inner speech? How does the movement from one to the other relate to the development of consciousness and language in general? 6. What is Vygotsky’s concept of Zone of Proximal Development? How is it different from assisted performance? How is it related to the other constructs of SCT (regulation, internalization)? 7. What are the research questions asked by SLA scholars working in a SCT framework? Which type of methodology do they use? Why? 8. Compare the tenets and theoretical underpinnings of the Input Hypothesis and the ZPD: learner’s role; learning process; goal of learning; role of the social environment. How does this comparison shed light on the common misunderstandings of SCT? 9. What are the goals of Donato (1994)’s study? Explain how various constructs of sociocultural theory are illustrated by his study. 10. What is microgenetic analysis? How is it illustrated in Donato (1994) and Nassaji & Swain (2000)? 11. In Donato’s (1994), how is collective scaffolding related to negative evidence? What are the advantages and disadvantages of scaffolding? 12. How does Donato assess the effect of scaffolding on language development? 13. What is the goal of Nassaji & Swain (2000)? What are the challenges? How is scaffolding operationalized in this study? What does the study show about learning in the ZPD and scaffolding? -review the “ZPD v i+1” document under Lecture. -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 12 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (11/28), 10am EST. -mark your calendar for the Wimba 2 session, Monday, December 5, 10:00-10:30am EST and 8:00-8:30pm EST. Two sessions have been scheduled in order that everyone may participate if they so choose. The session will be open “office hours” where I will be available to answer any questions you have. See you in class! Week 13 (starts 12/5, ends 12/11): Course Wrap Up This week we will review the theories of and concepts related to second language acquisition that we have discussed throughout this course. We will also conduct our Wimba 2 session, review for the exam, and (I believe) complete course evaluations. For this week, please -readVan Patten & Williams, chapter 12; -consider the optional readings deGuerrero (2000) and Storch (2002) (both in Additional Materials > Optional Reading); -read the Notes for Week 13; -post your answer to one of the discussion questions in the Week 12 Discussion Forum. The discussion questions will be posted by Monday (12/5), 10am EST; -review the Final Exam Information Folder under Course Materials to prepare for the Final Exam; -if possible, stop by one of the Wimba 2 sessions, Monday, December 5, 10:00-10:30am EST or 8:00-8:30pm EST. The session will be open “office hours” where I will be available to answer any questions you have; -complete the End of Course evaluation. (I do not have any information on this currently, but will post an announcement when I receive the information.) See you in class!