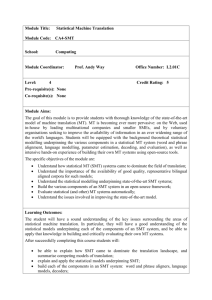

Rationale and aims of SMT

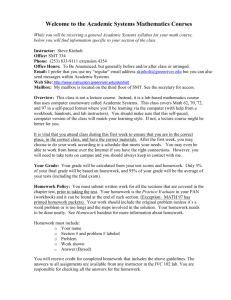

advertisement