Lecture 6 – Republican and Imperial Rome

advertisement

Lecture 6 – Republican and Imperial Rome

Prehistoric Italy: Around 1000 BC, the ancestors of the Romans, speakers of Italic

languages, pushed down into the Italian peninsula.

Etruscans: Little is known clearly of this people, but they seem to have arisen around

800 BC to conquer and rule over many of their neighbors (including Rome). They also

traded with distant lands; after 500 BC, they went into decline.

Royal Rome (753 BC? To 510 BC):

The Founding of Rome: Roman tradition held that Rome was founded in 753

BC by Romulus, later said to be a descendent of Prince Aeneas of Troy. The

Roman traditions of the monarchy period assert 7 kings ruled during it; most

historians now think this claim is likely questionable; many more kings likely

ruled. However, the Gauls destroyed all of Rome's early records in 390 BC when

they sacked Rome. Some time in the 6th century BC, a line of Etruscan kings

became the last monarchs of Rome.

Government: Rome's kings had the power of imperium—the ability to issue

commands and have them enforced through fines, physical punishment, or even

death. However, Kings were chosen by the Senate, not hereditary, and had to be

approved by the Assembly of citizens. The members of the Senate served for life,

providing counsel to the king and acting as the voice of the nobility. The curiate

assembly was made up of all citizens, divided into groups; each group voted on an

issue; the majority vote in the group determined that group's vote in the assembly.

It took approval by a majority of votes to then approve or deny measures brought

before it.

Family: The center of Roman life was the family unit. Men ruled the household;

women managed its affairs. A father could kill or sell his children into slavery,

but not his wife, who he could only divorce for serious offenses.

Clientage: Most people were enmeshed in a network of client-patron

relationships in which the patron aided his clients with economic and legal

problems and provided physical protection against violence, while the client

supported the patron politically, worked his land, and fought for him when

necessary. Some patrons were clients to men yet more powerful. Thus, roman

society was a web of patronage networks. Clientage was hereditary, though not

impossible to change.

Patrician and Plebian: The wealthy Patrician (noble) class held the top power

in society, for only Patricians could hold office, conduct religious ceremonies, or

sit in the Senate. Patricians only married Patricians. The Plebians were excluded

from power, though some became very wealthy through trade and artisanship;

most were poor farmers and minor artisans, however.

The Roman Republic (510 BC - ?)

End Point: As will be seen, historians dispute when exactly the Republic ends; it

seems to gradually shade into Empire. The first century BC or AD contains the

usual suspects when historians argue this.

Origins: In 510 BC, the noble families of Rome overthrew the Roman

monarchy, supposedly due to misbehavior by the last King, Tarquinius Superbus,

who ruled by violence and whose son was said to have raped a patrician woman,

Lucretia.

Constitution:

Consuls: The Consuls, two officials elected at the same time for one year

terms, assumed the powers of the kingship, though over time, the Romans

removed some powers to other officials. Their power of Imperium was

only unrestrained with regard to its use in the army in the field; within

Rome, citizens could appeal to the assembly. Futher, each Consul could

veto each other's actions and you only served once, then joined the Senate.

In a crisis, the Consuls could appoint a Dictator for 6 months, which held

unrestricted Imperium. This was for crises.

Other Officials: Quaestors ran the financial affairs of the state.

Proconsul was an office used to extend a consul's office for military

affairs only, so he could serve in the field over a year. Praetors served

judicial functions, as generals, and later as governors. The Censors

identified who was a citizen and to what group they belonged in the

Centuriate Assembly. They were the ones who conducted the yearly

census. They later gained the power to ban people from the Senate for

moral reasons.

Senate and Assembly: The Senate, because it endured and was small

enough to act effectively, largely took over the direction of foreign and

domestic affairs. The Centuriate Assembly was essentially the Roman

army of citizen-soldiers acting as a legislature. It was organized into

centuries—groups of a hundred men who could afford to buy and use

military gear. The assembly was divided into classes according to wealth

as well, according to what gear you had.

Struggle of the Orders: In the 5th - 3rd century BC, the Plebians and

Patricians struggled for control of the Republic. The Plebians won the

right to elect ten Tribunes in a plebian tribal assembly. The Tribunes

could veto any act of a magistrate or any bill proposed in a Roman

assembly or the Senate. In 367 BC, one Consul seat was opened to the

Plebians. In 287 BC, the Plebians secured a law which made the plebian

assembly's decisions binding on all Romans without needing Senate

approval. The nobiles—a collection of wealthy patrician and plebian

families now took control of the Senate and the state. (Some Patricians

had sunk into poverty by now.)

Conquest of Italy:

The Latin League, the Gauls, and the Latin War: In 493 BC, the

Romans joined the Latin League, an alliance of local states. Over time,

the Romans conquered much of central Italy in a series of wars interrupted

by the Gauls sacking Rome in 390 BC, which destroyed much of the

evidence of Rome's past. Despite this defeat, Rome bounced back,

defeating more of its neighbors and falling out with the Latin League,

which it defeated and assimilated after the Latin War (343 BC—338 BC).

Roman Conquests: Rome was generous to those it defeated, offering

some citizenship and others municipal status (local self-government).

Roman's citizen soldiers were rewarded by the grant of lands in conquered

territories, which they colonized. Colonists remained Roman citizens and

were linked by road networks to Rome. Local religion and culture was

left unmolested. Loyal allies could eventually gain Roman citizenship.

Southern Italy: Rome now turned its eyes south towards the Greek

colonies in Southern Italy. King Pyrrhus of Epirus tried to save these

cities from Rome in the early 3rd century BC, but his three victories over

Rome were so bloody he had to go home. (Source of the concept of

'Pyrric Victory').

Carthage and Sicily: For centuries, the Phoenician colony of Carthage,

located in modern Tunisia, had dominated the western Mediterranean. It

was currently involved in power struggles with the Greek colonies of

Sicily, Sardinia, and Southern Italy. Roman involvement in these politics

led to the first of three wars for control of the Western Mediterranean.

Carthage: Like Rome, Carthage was an oligarchic republic. Founded in

814 BC by Phoenician colonists, as an outpost for Phoenician trade. Over

time, it became independent as its home city, Tyre, fell to empire after

empire of the mainland, eventually becoming too weak to rule Carthage.

By the beginning of the 5th century BC, Carthage had become the

commercial center of the West Mediterranean region, a position it retained

until overthrown by the Roman Republic. The city had conquered most of

the old Phoenician colonies e.g. Hadrumetum, Utica and Kerkouane,

subjugated the Libyan tribes (with the Numidian and Mauretanian

kingdoms remaining more or less independent), and taken control of the

entire North African coast from modern Morocco to the borders of Egypt

(not including the Cyrenaica, which was eventually incorporated into

Hellenistic Egypt). Its influence had also extended into the Mediterranean,

taking control over Sardinia, Malta, the Balearic Islands and the western

half of Sicily, where coastal fortresses such as Motya or Lilybaeum

secured its possessions. Important colonies had also been established on

the Iberian peninsula.

Like Rome, Carthage was ruled by two Suffets, chosen by the oligarchic

council, whose power was checked by a popular assembly. Unlike Rome,

it didn't rely on citizen soldiers, but on a combination of mercenaries,

professional soldiers, forces from subject peoples, and the recruitment of

local natives around its colonies.

The First Punic War (264-241 BC): Similar in many ways to the

Peloponesian war: The Romans were unstoppable on land; the

Carthiginians at sea. It was largely fought in and around Sicily. The

Romans finally turned the tide by developing ships with boarding bridges,

allowing them to use their legionairres at sea to attack Carthaginian ships.

Carthage paid an indemmity and gave up its lands in Sicily.

Spain: Between wars, Carthage now enhanced its colonies in Spain to try

to raise money to be ready for the next war.

The Second Punic War (218-202 BC): The city of Saguntum allied itself

with Rome against Carthage in Spain, then stirred up trouble for Carthage.

Carthiginian general Hannibal, raised by his father to hate Rome, moved

against Saguntum and took it, then when Rome declared war, he took a

force across the mountains to Gaul, then across the Alps to invade Italy

from the north. Between 218 and 216 BC, Hannibal defeated the Romans

in three battles, each worse for Rome than the one before. This

culminated in Cannae, where in 216 BC, Hannibal defeated 80-90,000

men with a force of only 40,000 men, killing or capturing some 60-70,000

Romans. Despite the victory, however, Hannibal was unable to get

Rome's allies to defect or to capture Roman cities. In 215 BC, King Philip

V of Macedon allied with Hannibal, and from 215-205 BC, Hannibal was

able to roam Italy at will, but he was unable to break Rome. The turning

of the war was the appointment of Publius Cornelius Scipio to command a

force sent to Spain, where he conquered Carthage's colonies, causing huge

financial loss to Carthage. In 204 BC he invaded Carthage's African

lands, forcing Hannibal to go home. In 202 BC, he crushed Hannibal at

Zama and Carthage surrendered, losing most of its lands.

The Province System: Rome's new conquests became provinces to be

administered; no offers of citizenship were extended to Spain, Corsica,

Sardinia, or Italy. Instead, they were put under the command of governors

who possessed the Imperium within their lands without the limits which

restricted Consuls and other magistrates. Provinces paid tribute through a

system of tax-farming (privatized tax collection). Tax farmers owed a

fixed amount to the central government each year, but could collect more

than was due to the government. And they did, as they took the job to

MAKE MONEY FAST. End result—massive corruption.

The Conquest of the Hellenistic World:

Philip V: Philip V of Macedon was crushed by the Romans in 197 BC.

Antiochus III: This king of the Seleucid dynasty now chose to challenge Rome.

They crushed him at Magnesia in 189 BC and turned Greece and Asia Minor into

protectorates.

Other Wars: Perseus, son of Philip V tried to revolt and was crushed. The

conservative censor Cato pushed crusel punishment for anti-Roman factions and

revolts, including the 146 BC destruction of Corinth. In the same year, Rome

sacked Carthage, destroying it. Rome made so much money, it abolished

property taxes on citizens.

Greek Influence on the Early Roman Republic

Greek Influence: The conquest of Greece brought many Greek scholars,

teachers, engineers, slaves, etc, to Rome, along with sophisticated Hellenistic

culture.

Religion: Rome had a traditional pantheon of the Gods, some of whom were

connected to planets. They now tended to merge Greek Mythology with their

own by identifying Gods as equivalent—Jupiter and Zeus, Pluto and Hades,

Neptune and Poseidon, Juno and Hera, etc. The cults of Cybele the Great Mother

goddess and Dionysius/Bacchus were introduced from the east in the third century

BC.

Education: Education was a family responsibility, handled by tutors who were

often slaves. Roman education focused on making people moral, patriotic, and

conservative. Greeks added the study of philosophy, language, and literature to

the Roman curricula—'Humanitas'. Fluency in Greek was increasingly expected

of anyone with pretensions to social status. Some Romans, like Cicero, even

travelled to Greece to study.

Roman Imperialism:

Effects of War: The Second Punic war dispossessed many farmers and large

land holders gobbled up small forms to form plantations—latifundia. They

staffed the land with war captive slaves. Meanwhile, the old small farmers ended

up as city labor or as tenant farmers. The rich got richer and the poor poorer. The

result was conflict which threatened the Republic

The Gracchi: In the mid-second century BC, Tiberius Gracchus (168-133 BC)

set out to address this conflict. In 133 BC he became tribune on a platform of

land reform. However, another tribune vetoed his plans when he put them to the

tribal assembly. Tiberius convinced the assembly to fire said tribune and passed a

second bill. But his success undermined the rule of law in Rome. Feeling himself

in danger, he planned to illegally run for a second term as tribune. A mob of

senators and their followers now killed him, having no other recourse.

The Populares: New politicians arose like Tiberius who based their power on an

appeal to the people and the assemblies, not on influence among the wealthy. The

Populares were opposed by the Optimates, who backed the Senate's traditional

power.

Gaius Gracchus (159-121 BC): The tribunate of Gaius Gracchus, brother of

Tiberius, was marked by solid support for him from now re-electable tribunes.

Thus the Senate could not easily oppose him. Gaius set up colonies for veterans

and passing a law stabilizing grain prices. He also won the support of the

equestrians, wealthy men who supplied goods and services to Rome and helped

run its provinces. (This class got its name from being cavalrymen in the early

Republic due to affording their own horses.) Gaius bribed them with the right to

collect taxes in the Roman province of Asia in 129 BC. He fell from power after

he tried to extend citizenship to Rome's Italian allies. In 121 BC, he lost his

tribuneship and was killed in mob action with 3,000 of his followers.

Marius and Sulla: Gaius Marius (157-86 BC) was chosen Consul in 107 BC to

fight Jugurtha, king of Numidia (in NW Africa). He eliminated property

qualifications for the army, opening it to any and all volunteers—mostly

dispossed farmers and urban poor—who served for long terms. This began

turning the army from citizen-soldiers into professionals loyal mainly to their

generals. This now enabled generals to challenge the Senate. However, it also

made it much easier to keep armies in the field for long term wars.

Marius now crushed Jugurtha, but a guerilla war dragged on until his subordinate,

Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138-78 BC), stepped in and captured Jugurtha. Marius

stole the credit and they fell out.

War Against the Italian Allies (The Social War): 90-88 BC. Rome's Italian

allies now revolted against Rome, seeking equality. Rome gave in and granted

them citizenship and local autonomy for their municipalities.

Sulla's Dictatorship: Sulla was elected Consul for 88 BC and used his power to

crush Marius and his followers. He now became dictator, and in theory, restored

the traditional order and the power of the Senate. But in actuality, he showed that

anyone with an army could not take over Rome.

Fall of the Republic

Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar: In 70 BC, Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53

BC) and Gnaeus Pompey (106-48 BC) were elected Consul; they repealled most

of Sulla's reforms. Pompey then fought a campaign to wipe out the

Mediterranean pirates and returned in 62 BC as a hugely popular figure. Crassus

feared his rising power and allied himself to Gaius Julius Caesar (100-44 BC).

The First Triumvirate: To the surprise of all, Pompey disbanded his army and

staged no coup. He wanted a grant of land for his men, but the Senate refused,

causing him to ally with Crassus and Caesar.

Rise of Caesar: Elected consul in 59 BC, Caesar now carried out the

Triumvirate's plans. He then secured the governorship of Gaul and spent 58-50

BC in Gaul, conquering it in a series of wars made famous by his own historical

account of it, which would later become a major part of latin studies:

Commentaries of the Gallic War. He conquered Gaul so thoroughly, it remained

loyal to Rome until the 5th century AD. In his absence, Crassus died fighting the

Parthians at Carrhae in 53 BC. Pompey now allied with the Senate against him.

The Rubicon: At the end of his ten years as governor, the law required Caesar

lay down his Imperium powers as governor and go home to Rome. Instead, he

marched his legions to the Rubicon, southern border of Gaul, and crossed the

river with them to attack Rome. From 49-45 BC, he fought Pompey and other

challengers, crushing them all and emerging triumphant.

Caesar in Power: He now took on many offices and became effectively dictator

without the title. It is unclear what his plans were or if he even had any. On

March 15, 44 BC, a group of Senators and relatives, the most famous of whom

was Marcus Junius Brutus, who Caesar had spared from execution despite Brutus

having aided Pompey against Caesar, stabbed him to death. According to

Eutropius, around sixty or more men participated in the assassination. He was

stabbed 23 times. According to Suetonius, a physician later established that only

one wound, the second one to his chest, had been lethal.

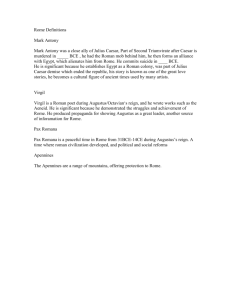

Second Triumvirate: Caesar's heir was his nephew, Octavian (63 BC-14 AD).

He allied with two of Caesar's officers—Marcus Antonius (83-30 BC) and

Lepidus (died 13 BC)-- to form the Second Triumvirate. They now crushed

Caesar's assassins but fell out with each other. Antonius allied with Cleopatra,

Queen of Egypt, last of the Ptolmaic Dynasty. At Actium in 31 BC, Octavian

crushed Anthony and Cleopatra; they both killed themselves. Octavian ruled

alone now, but had to figure out HOW to rule.

The Augustan Principate:

Princeps: Octavian was now given the title of Augustus by the Senate as an

honor. Augustus (Octavian) created a monarchy swaddled in Republican

clothing, taking up the title of First Citizen ("Princeps"), leaving Republican

institutions in place while basically neutering them. Later, his successors took the

title of imperator ('Emperor', or the holder of the Imperium). In 27 BC, he took

Proconsular command of Spain, Gaul and Syria and retained a consulship in

Rome; 20 of Rome's 26 legions were in his lands, giving him effective power over

the Senate. The Senate gave him many honors, including the title "Augustus",

which connoted veneration, majesty, and holiness.

Administration: Augustus reformed administration to remove corruption and

controlled election to office so as to elevate men of talent, both Italian and

provincal. The Senate was treated with respect but rendered mainly a talking

shop and source of adminstrators. His reign was a time of peace and prosperity,

generated by wealth from newly conquered egypt, an end of violence, a revival of

small farming and a vast program of public works.

New Services: The city of Rome was utterly transformed under Augustus, with

Rome's first institutionalized police force, fire fighting force, and the

establishment of the municipal prefect as a permanent office. The police force

was divided into cohorts of 500 men each, while the units of firemen ranged from

500 to 1,000 men each, with 7 units assigned to 14 divided city sectors. A

praefectus vigilum, or "Prefect of the Watch" was put in charge of the vigiles,

Rome's fire brigade and police.

The Army and Defense: The military was now fully professionalized. You

served for 20 years with good pay, then could settle in a military colony and get

your own land on retirement with a pension. 300,000 men served, guarding the

frontiers. Many retired soldiers married local women, helping to assimilate

conquests and bringing Roman culture.

Religion and Morality: A century of political strife and civil war had

undermined Roman society. Augustus believed it necessary to restore Roman

moral fiber by attacking adultery and divorce, by rebuilding temples and restoring

traditional rites, and by encouraging marriage and production of legitimate

children. Augustus was deified and worshipped after his death; in time, the

worship of divinized emperors would become a sign of loyalty to the state—a

major problem for the Jews and Christians, who refused to do so.

Civilization of the Ciceronian and Augustan Ages

The Ciceronian Age (The Late Republic):

Cicero (106-43 BC): Marcus Tullius Cicero (January 3, 106 BC –

December 7, 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, political theorist,

and philosopher. Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest

orators and prose stylists. Many of his speeches, books, and letters

survive, giving us more information than usual about him. Cicero looked

to law, custom, and tradition to produce both stability and liberty. He

hoped to reform the ruling class and convert it from a venial system of

hereditary wealth to an aristocracy of the talented and virtuous from all the

classes. He was a contemporary of Julius Caesar, but supported the Senate

and was killed by those avenging Caesar's death.

Law: It was in this period that the idea of a law not based mainly on

custom truly arose, the idea of the jus gentium, "law of peoples." The

Romans also drew upon the idea of natural law, jus naturale, developed

by the Greeks.

Poetry: Two of Rome's greatest poets, Lucretius (99-55 BC) and Catullus

(84-54 BC) lived in this period. Hellenistic poets wished to educate;

Lucretius followed this tradition in writing his De Rerum Natura ("On the

Nature of Things"), which laid out the scientific and philosophical theories

of Epicurus and Democritus.

Catallus: The poetry of Catallus, by contrast, is deeply personal, writing

about the ordinary life of the Roman upper class and love, and sometimes

rather explict.

The Age of Augustus: This was the Golden Age of Roman literature. Support

for art flowed from the wealth of the Princeps.

Virgil (70-19 BC): Most important of the Augustan Poets. He wrote on

many topics, but his greatest work was the Aeneid, which tied together

Roman and Greek Mythology by showing the story of Prince Aeneas of

Troy, whose descendents would found Rome. Aeneas personifies Roman

virtues of "duty, responsibility, serious purpose, and patriotism."

Horace (65-8 BC): Quintus Horatius Flaccus was another poet, whose

Odes glorify the new Augustan order, the imperial family, and the empire.

(Despite the fact that he had fought as a soldier against Augustus, and had

his family lands confiscated. He knew which way the wind blows.) He

wrote many Latin phrases that remain in use (in Latin or in translation)

including carpe diem, "seize the day"; Dulce et decorum est pro patria

mori; and aurea mediocritas, the "golden mean." His lyric poetry

(designed for singing) was written in Greek metres.

Ovid (43 BC – 18 AD): He wrote love elegies which showed the

sophistication and lose sexual conduct of the Roman aristocracy. Ovid was

generally considered the greatest master of the elegiac couplet. He is most

famous for his Metamorphoses, an epic length poem which adapts various

Greek myths about changes (often magical) into a history of the world

from creation. (Which, ironically, is written in dactylic pentameter, like

the Aeneid and Homer's epics.) Ovid was banished in AD 8, possibly due

to offending Augustus with his tales of Roman decadence when Augustus

sought moral reform.

History: Livy (59 BC-17 AD) wrote his History of Rome in this period, a

critical source for our knowledge of Rome's past. It covered everything

from 753 BC to 9 BC. Only one fourth of it survives; Livy sought to

glorify Rome's greatness and show how its history embodied its virtues.

Architecture and Sculpture: Augustus engaged in a massive project of

cleaning up and rebuilding Rome. On his deathbed, Augustus boasted "I

found Rome of clay; I leave it to you of marble;" he rebuilt substantial

public areas with marble and other sturdier methods. He massively

improved the city's water supply.

Imperial Peace and Prosperity (AD 14 to 180)

Imperator and Caesar: The first dynasties of Roman emperors claimed the

leadership of Rome by two rights—their holding Imperium (control of the

military) and connection to the Imperial house. From 14 AD to 68 AD, the

relatives of Augustus (Tiberius, "Caligula" (Gaius), Claudius, Nero) governed the

empire. After Nero's death, a series of military leaders took over, followed by the

Flavian dynasty (69-96 AD, Vespasian, Titus, Domitian (persecutor of the author

of the Book of Revelations)), descended of Vespasian, who put down the

rebelling generals. With the end of the Flavians, a series of emperors took the

throne who each adopted an heir instead of picking a blood relative as heir:

Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antonius Pius, and Marcus Aurelius (96-180 AD for

the five collectively, sometimes referred to as the 'Five Good Emperors').

Marcus Aurelius was succeeded by his much less competent son Commodus

(180-192 AD); the movie Gladiator shows a somewhat distorted view of

Commodus' reign, but he was not a very good ruler, and the best years of Rome

end with him.

Administration: The Empire was a collection of cities and towns with associated

countryside. The Romans raised cities and towns to self-governing municipality

status, and enlisted local elites to run local areas with a layer of Roman

management above the municipality level. Over time, however, growing

bureaucracy shrank the autonomy of the municipalities.

Peak Size: Under Trajan, the Roman Empire hit its territorial height with the

occupation of Dacia (modern Romania) in 106 AD. This is why Romanian is a

Romance language today (a language derived from Latin, not Slav, German, or

Greek as most East European languages are). Trajan attempted to crush Parthia,

but after much success, died of heat stroke. His successor, Hadrian, retrenched,

building defensive walls and ceasing expansion. The most famous of his defenses

is Hadrian's Wall in Britain; portions of it still stand today. To maintain morale

and keep the troops from getting restive, Hadrian established intensive drill

routines, and personally inspected the armies. Although his coins showed

military images almost as often as peaceful ones, Hadrian's policy was peace

through strength, even threat.

Literature: The time from 14 AD to 180 AD is seen as the Silver Age of Roman

Literature. Silver Age writers were gloomy, negative, and pessimistic and

avoided discussing the present to stay clear of imperial wrath. Scholarship and

escapist literature in Greek predominated; poetry dwindled.

Architecture: The prosperity and relative stability of the first two centuries of

Imperial Rome brought Roman architecture to full flower. The Romans could

now build huge building projects with the semi-circular arch and concrete. The

Colisseum in Rome, though now badly damaged, is a classic example of Roman

architecture on the grand scale. The biggest impact, however, was the Roman

road and aqueduct networks.

Society: In the first century AD, the Empire worked very well; by the second

century, trouble was arising. As municipalities lost their autonomy, emperors had

to force elites to take up municipal offices because they didn't want the revenue

raising responsibilities unless they got real power with it. Prosperity was

declining and the government needed ever more money to run the army and

bureaucracy, to appease the roman mob with "bread and circuses", and to defend

the fronteirs. This led to various economy damaging expedients like debasing the

currency.

Apartment Houses: In the city of Rome, over 500,000 people lived (as

compared to 20,000 or so for other cities). The result was that most people lived

in insulae (literally 'islands', which were apartment buildings). They collapsed

easily and burned frequently. The floor at ground level was used for tavernas,

shops and businesses with living space on the higher floors. Because of the

inherent safety issues and extra flights of stairs, the uppermost floors were the

least desirable, and thus the cheapest to rent. Living quarters were typically

smallest in the building's uppermost floors, with the largest and most expensive

apartments being located on the bottom floors. The insulae could be up to six or

seven stories high (some were even 8 or 9 stories high- these very tall buildings

were being built before the height restrictions). A single insula could

accommodate over 40 people in only 400 square meters (4305 sq. feet), however

the entire structure usually had about 6 to 7 apartments, each had about 200

square meters (2152 sq. feet). Some had running water, others did not.

Domus: A domus was the form of house that wealthy families owned in ancient

Rome and almost all the major cities of the Empire. (The middle classes and the

poor were housed in crowded apartment blocks, known as insulae, while the

country houses of the rich were known as villas). The domus included multiple

rooms, and an indoor courtyard: the atrium, which was the focal point of the

domus, off which were cubicula (bedrooms), an altar to the household gods, a

triclinium where guests could lie on couches and eat dinner whilst reclining, and a

tablinum (living room or study) and cellae(shops on the outside, facing the street).

In cities throughout the Roman Empire, wealthy homeowners lived in one story

buildings with few exterior windows. Glass windows weren't readily available:

glass production was in its infancy, and the cost would have been prohibitive, but

this exterior blankness did give the occupiers the advantage of protecting

themselves from outside noise, intruders, and the elements. Homeowners tended

to view their exterior walls as public property, and they quickly became filled

with political graffiti. Wealthy homeowners often rented out the two front rooms

of their homes to merchants if they lived on busy streets. Thus a wealthy Roman

citizen lived in a large house separated into two parts, and linked together through

the tablinum or study or by a small passageway.

Rise of Christianity

Jesus of Nazareth: Almost all of the major religious founders (Buddha, Moses,

Jesus, Mohammed) pose a similar problem: We only know them through sacred

texts written years to decades to centuries after their death. As a result, it is hard

to separate myth from fact. Jesus was born in Judea, possibly in the tail end of the

reign of King Herod. While in theory our calendar sets 1 AD as the year of Jesus'

birth, Jesus could well have been born anywhere between ten years earlier or later

than 1 AD. In his adulthood, he became a travelling teacher of a type common to

the religious ferment of his time, a rabbi.

The Four Schools Of Judaism: Josephus, a first century Jewish historian, attests

to four major schools of Jewish thought at the time of Jesus in the first century:

The Essenes, the Revolutionaries, the Sadducees and the Pharisees.

The Essenes: The Essenes were apocalyptic mystics who held to a

collection of religious texts rejected by other Jews, such as the Book of

Jubilees and "Malhama" (The End Time Great War), under the leadership

of the "Teacher of Righteousness". They withdrew from society and lived

communally and celibately in the wilderness. They thought the end of the

world was coming soon and they saw themselves as preparing to fight on

God's side. Some scholars think Jesus either was an Essene or was

influenced by the Essenes.

The Revolutionaries: Some Jews were preoccupied with overthrowing

the Romans to defend Jewish society and culture from Roman

encroachment. They looked to the past Jewish revolt of the Maccabees

against the Selucids for inspiration (forgetting it was Rome who finally

helped the Maccabes get independence.) The Bible refers to them as

'Zealots'.

The Sadducees: The Sadducees represented a conservative strand of

Jewish religious thought. They were essentially the temple party, holding

to older Jewish religious ideas and practices against the Pharisees, and

supporting the line of Hasmonean priests who took over Temple duties

during and after the Maccabean revolt against the Selucids. They rejected

the metaphysical speculations of the Pharisees (souls, angels, the

resurrection of the dead) in favor of literal intepretation of the Hebrew

Bible. They would be destroyed with the sacking of the Second Temple in

70 AD.

The Pharisees: The Pharisees were, depending on the time, a political

party, a social movement, and a school of thought among Jews that

flourished during the Second Temple Era (536 BC–70 AD). They

emerged during Selucid rule as resistors to the cultural assimilation of the

Jews attempted by the Selucids, calling on all Jews to follow the laws of

the Torah, especially the rules for ritual purity. The Pharisees combined

the written Torah with oral traditions passed down by lines of teachers, the

rabbis, a great system of commentary to expand and comprehend the Laws

given by God. Further, the Pharisees were more prone to metaphysical

speculation, believing in concepts such as life after death, the soul, angels,

etc. The Pharisees encouraged the formation of local synagogues for the

study of the Torah and the oral law (which would eventually become the

Talmud). Like the Prophets, the Pharisees emphasized good deeds and

compassion for others over ritual sacrifice, the purification of the self.

Jesus the Teacher: Around 30 AD, Jesus began a several year campaign of

travelling and teaching, recruiting disciples and preaching to crowds. Jesus spoke

of the coming Messiah and the Kingdom of God, which was a spiritual kingdom,

not a material one, though he urged people to act righteously here on Earth. He

laid out his moral code in the Sermon on the Mount: humility, generosity,

kindness, love, and charity. Jesus won a strong following, especially among the

poor, but this caused the religious leadership of the time, embodied in the

religious assembly, the Sanhedrin, to turn on him and seek his death. He was

crucified by the Romans and his followers believed that he rose from the dead on

the third day and that he was the Messiah and that they now had a duty to preach

his message to all.

Paul of Tarsis: Without Paul (born Saul of Tarsis), Christianity might have

remained a small Jewish sect. Paul was a Hellenized Jew, well educated and

literate, but also a Pharisee. Originally, he helped to persecute Christians, but

then he underwent a vision on the road to Damascus (around 35 AD) and

converted to Christianity, insisting on becoming one of the Apostles (the leaders

of early Christianity; all the rest had been hand-picked by Jesus as his inner circle

of followers. They were reluctant, understandably, to accept Paul.) He clashed

with James, 'brother' of Jesus (James might have been anything from an actual

brother to a half-brother to a cousin. There are translation issues), who insisted

converts keep the Jewish law. Paul became the Apostle to the Gentiles, spreading

Christianity to non-Jews and not requiring them to keep the Law of Moses.

(Gentiles = non-Jews in Jewish parlance). Faith was the key to salvation, not

ritual practices.

Practices: Early Christians practicised baptism as an initiation ceremony to wash

away sin and a common meal known as the agape (love feast), followed by the

Eucharist, a celebration of the Lord's Supper modelled on Jesus' last meal with his

followers. Unleavened bread was eaten and unfermented wine drunk. There were

also prayers, hymns and readings. Some congregations had a tradition of

prophesying and its interpretation (similar to modern 'speaking in tongues' and

other activities of Pentecostal churches).

Organization: Early Christianity was divided into mostly independent

congregations which had a certain loyalty to their founders and the Apostles in

Jerusalem, but all ties between different communities were basically informal. By

the second century AD, every city had a leader known as the bishop (which meant

"overseer"), but every city was basically independent. The idea of Apostolic

Succession linked lines of bishops back to the Apostles; this continuity was the

source of their authority. Bishops came together in councils to settle disputes and

theological issues, though empire-wide councils only became possible after

legalization. Christianity was most common among the urban poor.

The Council of Jamnia (90 AD): Leaders of the Pharisaic tradition came

together to formulate a joint religious canon and to set out guidelines for Jewish

adaptation to the world in the aftermath of the sack of the Second Temple. This

meeting is the root of most modern Jewish sects and at this time, the Jews threw

any book originally written in Greek (the Apocrypha) out of their canon. Martin

Luther did likewise centuries later, which is why Protestants have a smaller bible

than Catholics, who go by the second century BC Septuagint for the Old

Testament.

Persecution: Christians refused to worship the Imperial line. This was treason

and there were periodic waves of persecution of Christians. By 100 AD, being a

Christian was a crime.

Rise of Catholicism: Until the Council of Nicea (325 AD), there was no single

definitive bible or creed, but most of the Christian churches shared a body of

teachings which would undergird that council's decisions. This body came to be

known as Catholic ("universal") or orthodox. Those holding other opinions were

called "heretics". By 200 AD, an orthodox religious canon and theology had

emerged, though it was only at Nicea that the whole body of the Church would

put a final seal on such matters.

Rise of the Roman Church: The Roman Church was able to trace its origins

back to visits by both Peter and Paul (and their martyrdoms in that city). It traced

its apostolic succession back to Peter himself, giving it a special pre-eminince in

the early church, though the churches of Antioch and Jerusalem (and later

Constantinople) also held special prominence.

The Gnostics: Gnosticism began as a pre-Christian philosophy; some Christians

fused it with Christian ideas, forming one of the larger heretical groups of the

early church. Gnosticism (from Greek gnosis, knowledge) refers to a diverse,

syncretistic religious movement consisting of various belief systems generally

united in the teaching that humans are divine souls trapped in a material world

created by an imperfect spirit, the demiurge, who is frequently identified with the

Abrahamic God. The demiurge, who is often depicted as an embodiment of evil,

at other times as simply imperfect and as benevolent as its inadequacy allows,

exists alongside another remote and unknowable supreme being that embodies

good. In order to free oneself from the inferior material world, one needs gnosis,

or esoteric spiritual knowledge available only to a learned elite. Jesus of Nazareth

is identified by some (though not all) Gnostic sects as an embodiment of the

supreme being who became incarnate to bring gnosis to the Earth. Gnostic sects

thus tended to reject the value of the human side of Jesus' nature in favor of the

divine. The Gospel of Thomas is one of many gnostic Christian writings which

were lost and suppressed after Nicea.

The Crisis of the Third Century:

The Severan Dynasty (193-235 AD): In 192 AD, Emperor Commodus was

strangled by a professional wrestler named Narcissus; five seperate men tried to

claim the throne in 192-3. Septimus Severus (193-211 AD) emerged on top,

beginning a period in which succession to the throne destabilized and civil wars,

coups, and invasions became more frequent.

Administration: The Severan Dynasty made serious changes in the army and

government. He purged the Senate of enemies, raised the pay of soldiers,

increased the number of legions and began a rise in recruitment of peasantry from

the less Romanized provinces and even of actual barbarian foreigners. The army,

as in the late Republic, was increasingly loyal more to its generals than the state.

And it put a heavy burden on the citizenry. However, he also stomped out the

corruption and license of the reign of Commodus.

Economy Difficulties: Rising inflation and debasement of the currency undercut

the economy. Public order declined due to endless wars on the fronteir soaking

up all troops. Heavy burdens on the people led to revolts.

The Social Order: The state grew militarized; your clothing denoted your social

status / rank. The government granted privileges to the honestiores (senators,

equestians, municipal aristocrats and soldiers), while keeping everyone else down

(the humiliores).

Civil Disorder: By the late third century, the military was largely made up of

Germanic mercenaries and an Imperial heavy cavalry force. They supported coup

after coup by would-be emperors. From 235 to 268, 14 emperors reigned in 33

years, before the rise of the Illyrian Emperors. These revolts left holes in the

border defenses for barbarians to invade.

The Late Empire

The Fourth Century and Imperial Reorganization: The reigns of Diocletian

(284-305 AD) and Constantine (306-337 AD) ended the rising anarchy and set up

the final form of Roman government in the period up to the final collapse of the

Western half of the Empire.

Diocletian: Diocletian came to the throne by military means, but set out to create

a coherent system for peaceful succession and defense—The Tetrarchy. Two

co-emperors would rule, one for the West, one for the Eastern Empire, known by

the title of Augustus. Each would pick an heir who would help him rule, known

as the Caesar. Diocletian forced his co-emperor, Maximian, to resign with him in

305, so as to set an example for peaceful succession. Though it didn't work as

civil war broke out shortly thereafter...

Constantine: Emperor Constantine won the civil war, then made Christianity a

tolerated religion and ruled the empire from a new city he built in Thrace—

Constantinople, now known as Istanbul in Turkey. It would endure for over a

thousand years.

Dominus: The Emperor was now known as Dominus ("lord") and viewed as

divinely chosen. He was effectively an absolute monarch who men prostrated

themselves before.

Administration and Finance: The bureaucracy was carefully separated from the

army and spied on by informers and spies. But the finances of the empire,

especially in the west, were a mess. Peasants couldn't pay their taxes and the

upper classes fled to country estates for the same reason; peasants bound

themselves to the estates of the upper classes to avoid responsibility for taxes.

Division of the Empire: In the late fourth century, the Huns were on the move

on the steppes of modern Russia, pushing other tribes west into Europe. The later

members of the Constantinian Dynasty divided the Empire into halves again to

make it easier to coordinate local defense.

Adrianople: The defeat of Roman legions by Visigothic cavalry at Adrianople in

378 AD presaged trouble for the empire, whose military would prove inadequate

in the West to deal with the new age of Cavalry with the stirrup.

Deurbanization in the West: The western cities lost purpose and strength as the

wealthy moved to rural estates and fled Imperial duties and burdens. Life

centered around the villa (Roman estate). Coloni (tenant farmers) served the lord

of the villa in return for economic aid and protection. Roads and police services

crumbled. Only Christianity and the Imperial Army formed links between

isolated communities, but the Army was coming apart for lack of money to pay

for it.

The Roman East: Predominately Greek speaking, this area was wealthier and

more urbanized and less the target of barbarian invasion. It would weather the

fall of the West and evolve into the Byzantine Empire.

The Final Collapse: On the death of Theodosius the Great in 395 BC, he was

followed by a child-emperor, Honorius (born 384, ruled 395-423). Honorius was

weak and palace intrigues among his servants undermined the defense of the

borders. Barbarian tribes—Franks, Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, and others,

began to infiltrate the empire, taking over entire provinces. In 410 AD, the last

roman legions abandoned Britain to try to shore up Gaul's defenses, at the same

time that the Visigoths sacked Rome.

As the empire declined, pressure from the growing empire of the Huns drove ever

more tribes into the empire. Finally, in the 440s and 50s, Atilla the Hun led his

forces into the empire in a series of raids that turned into conquest attempts.

Despite Atilla's defeat at Chalons-sur-Marne in 454 AD by an alliance of

barbarians and Romans, the Western Empire had now collapsed to be little more

than bits of Africa and Gaul combined with Italy. Rome was now sacked in 455

by the Vandals, who now controlled Northern Africa. What was left was

dependent on aid from the Eastern Empire. With the deposal of Romulus

Augustus (himself a puppet figurehead for his father, a military commander) in

476 AD and the fall of Italy to the Ostrogoths under Theodoric the Great in the

490s AD, the western empire quietly faded away.

Triumph of Christianity

Syncretism: In the fourth and fifth century, Romans sought the aid of strong

personal dieties; many folk melded together old religions and gods (syncretism).

Imperial Persecution: In 303, Diocletion launched the most thorough, though

brief persecution of Christians; like previous attempts, it failed. Ancient states

could not muster the thoroughness needed to crush a popular religion if its

adherents remained firm.

Constantine and Recognition: After his conversion, Emperor Constantine made

Christianity a tolerated religion in 313 AD through the Edict of Milan. In 394

AD, emperor Theodosius outlawed paganism and made it the official religion of

the empire. In the east, the church ended up as an arm of the state; in the west,

weakened states meant more autonomy for the Church. Indeed, western Bishops

could sometimes force leaders to do penance, as Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, did

to Emperor Theodosius in 390 AD.

Arianism: At the time of Christianity's toleration, Christians were divided

between the ideas of Arius of Alexandria (280-336 AD) and the more orthodox

view of Jesus' divinity. Arius taught against the Trinity of orthodoxy (which

taught God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost had all existed together as one

being from eternity and shared one substance); Arius taught that God the Father

and the Son did not exist together eternally. Further, Arius taught that the preincarnate Jesus was a divine being created by (and possibly inferior to) the Father

at some point, before which the Son did not exist. Jesus was a created divine

being. The Arian missionary Ulfius would go on to spread Arian ideas among

many of the Germanic tribes that invaded the empire in the 4th-5th century AD.

The Council of Nicea (325 AD): This council was called by Constantine to settle

the disputes. 1,800 Bishops were invited—somewhere between 250 to 320

attended. It laid out the Nicene Creed, which taught Trinitarian, Orthodox

theology.

The Canon of the Bible: A series of councils worked at the problem of laying

out the exact content of the Bible; the issue was finally settled in 393 AD at the

Council of Hippo. In 400 AD, Saint Jerome translated the bible into Latin; his

work, the 'Vulgate', would remain standard for Western Catholics until the

Reformation.

Art and Culture in the Late Empire

Art as Conflict: Christianity and Paganism's clash in the last years produced

large amounts of polemnic and propaganda.

Preservation of Classical Culture: One of the major accomplishments of this

period was the saving of classical literature of times past despite declining

literacy; Christian monasteries would emerge as a major vehicle of this work.

Scholars copied old works and also wrote condensed versions of ancient texts, as

well as learned commentaries and grammars.

Christian Writing: In 400 AD, Saint Jerome (late 4th to early 5th century AD)

translated the bible into Latin; his work, the 'Vulgate', would remain standard for

Western Catholics until the Reformation. Eusebius of Caesarea (ca 260-340 AD)

wrote Ecclesiastical History, which developed a Christian theory of history as the

working out of God's will.

The works of Saint Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (354-430 AD) show the

interrelationship between Pagan and Christian scholarship in this period.

Augustine deployed his classical (and Pagan) Roman education in rhetoric and

philosophy to defend and articulate Christian theology. His Confessions (397-8

AD) (autobiography) and The City of God are his greatest works. The City of

God (410 AD) was a response to the Sack of Rome in 410 AD, which many

feared was a punishment for the abandonment of paganism. The book presents

human history as being a conflict between what Augustine calls the City of God

and the City of Man (a conflict that is destined to end in victory for the former).

The City of God is marked by people who forgo earthly pleasure and dedicate

themselves to the promotion of Christian values. The City of Man, on the other

hand, consists of people who have strayed from the City of God. This was his

way of seperating God's church from the Roman Empire; the latter might fall due

to corruption, but God's church would endure.