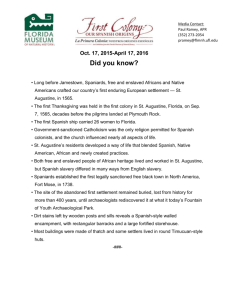

St - Defenders of the Catholic Faith

advertisement