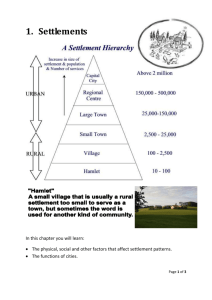

document index

advertisement