III – Limiting Features of Consumer Credit Reporting

advertisement

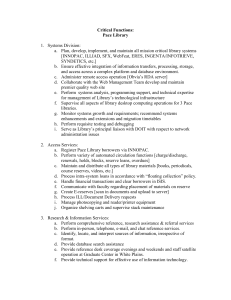

Working Paper Brazilian Perspectives on Privacy in the Context of Credit Reporting Antônio José Maristrello Porto* Many advanced economic societies have some form of a credit reporting agency (CRA) that collects information on individuals’ financial condition, including their history of repayment of loans. Before extending credit, potential lenders consult the CRA. A surprising number of countries lack a robust CRA. This article analyzes the benefits and costs that would come from the introduction or the enhancement of a CRA in such a society. The creation and implementation of a CRA reduces the asymmetry of information between creditor and debtor and thus reduces the transaction costs involved in their relationship, increasing overall wealth. The efficiency gains could result in lowered average interest rates and greater access to credit. However, this increase in society’s welfare may be offset by the loss of privacy and other costs falling on individuals. In addition to the attendant loss of privacy to which many object, another cost of a credit registry agency falls on those who will have false negative information about them appearing in the CRA. The desirability of the creation, implementation and enhancement of a CRA depends primary on how the gains of efficiency in the credit market will be distributed, where the costs of false negative information falls, and how much privacy individuals are willing to give up in exchange for credit conditions. The final section of this paper presents the results of a survey to try to measure how much privacy Brazilians’ consumers are willing to give up for better credit conditions. *Getulio Vargas Foundation/CPDE – Direito Rio. Praia de Botafogo, 190, 22250-900, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; e-mail: antonio.maristrello@fgv.br. Antônio José Maristrello Porto. I am very grateful to Randall S. Thomas and Hans-Bernd Schäfer, who made comments on previous drafts. I am also grateful to Gustavo Sampaio de Abreu Ribeiro and Heitor Campos de A. Guimarães for valuable research assistance. Responsibility for errors rests with the author. I – Introduction A noncredit transaction is likely to be less regulated than a credit transaction. For examples, the regulation of cash retail sales of refrigerators is lighter than the regulation of such sales made with credit. This article shed some light on the importance of information in a credit transaction operation. The relation between lenders and borrowers may be adversely affected by asymmetric information, causing an inefficient allocation of credit. The inability of lenders to evaluate the real intentions of potential borrowers may prevent the extension of credit, or force lenders to charge borrowers higher rates, which in turn may cause adverse selection in the credit market.1 A potential method to reduce asymmetry of information between lenders and borrowers is the creation of a credit reporting agencies (CRA). 2 In some countries, positive credit reporting agencies (positive-CRA) and negative credit reporting agencies (negativeCRA)3 are created and maintained by government (public credit registries), by private institutions (private credit registries), or by both.4 If a CRA may reduce asymmetry of information and thus to foster the credit market, why do some countries not have a fully functioning one? The aim of this article is to analyze, from a law and economics point of view, the pros and the cons of the creation and the implementation of a CRA in any given country. Even though my analysis uses Brazilian for illustration – a country without a fully functioning positive-CRA yet – as a model,5 I believe that my analysis is also pertinent for other countries. Moreover, given See (Stiglitz and Weiss 1981) In a prefect competitive market, lenders and borrowers would have perfect information. Lenders would have all the necessary information about borrowers past credit history and, thereafter, could adjust the price and the limits of a loan in a case by case base. However, borrowers have strong incentives to fail to disclose information, known to her, that if communicated to the lender would have made the loan fall through or imputed her more expensive interests’ rates. 3 CRAs may issue reports that “range from simple statements of past defaults or arrears – ‘‘black’’ or ‘‘negative’’ data – to detailed reports on the applicant’s assets and liabilities, guarantees, debt maturity structure, pattern of repayments, employment and family history – ‘‘white’’ or ‘‘positive’’ data” (Jappelli and Pagano 2002, p. 2022). 4 I acknowledge that the difference between privately and publicly run CRAs is relevant in terms of functioning rules, level of access, available information etc; however, for our purposes in this paper – analyzing the impact of such credit information sharing system on asymmetry of information in the credit market – the nature of who runs the system is less important. For this reason, throughout this paper I will only distinguish between private and public CRA when relevant. 5 By the end of the eighties there was an intense deregulation of the bank sector in Brazil and the Real Plan allowed for economic stabilization, which culminated in the rise of foreign banks that 2 1 2 that the desirability of CRAs also depends on the design of such institutions, it is highly advantageous to compare different institutional designs of CRAs.6 The creation and implementation of a positive-CRA in a country may reduce the asymmetry of information between lender7 and borrower, and thus, reduce the transaction costs involved in their transactions, increasing society’s overall wealth. However, the distribution of these gains to consumers, in terms of lower interest rates, increases in the amount of available credit, and better credit conditions, will depend primarily upon the level of competition in the credit market.8 Furthermore, there are political choices that must be made between the benefits of having more and cheaper credit available under a fully functioning positive-CRA, and its costs, including the loss of consumer privacy and the costs of having false negative information9 about individuals appearing in the CRAs. In order to address this issue, I conduct a survey to try to measure how much privacy Brazilians’ consumers are willing to give up for better credit conditions. In Section II, I describe the process of the creation of a positive-CRA, point out why it is important, and discuss some of its positive and negative sides. In Section III, I highlight some restrictive features of the positive-CRA, its limits as a credit policy and its dilemmas. I also briefly discuss how the institutional design of CRA has important effects on its social desirability. In Section IV, I use an empirical survey to shed further lights on the link between privacy and better credit conditions for Brazilians’ consumers. Section V contains some concluding remarks. dominated the technology of the credit analysis. Despite all these facts, Brazil still lacks a fully functioning CRA. See (Pinheiro and Moura 2001). 6 I will, when necessary, analyze the already established institutional design in other countries and try to make some corporations. 7 During the text I will use lenders to refer to banks, department stores and small retailers, but will make differentiation when necessary. This is an important point because the effects of a fully functioning CRA may be different to each of these creditors. 8 In the absence of competition the interest rate for the good debtor may fall and the interest rate for the bad debtor may increase. However, the average interest rate will remain the same, if the creditor knows the quota of bad debtors but not the individual. The efficiency gain in this situation is that a pooling equilibrium and cross subsidization of bad debtors by good debtors is avoided and that more credits are given to good and less to bad debtors. 9 By false negative I do not mean only negative information – false past defaults or arrears, rather I mean all type of false information that was erroneously reported to positive-CRA or processed by it and that results in worse credit history reports to borrow than her in fact has. 3 II – Positive Consumer Credit Reporting – an overview It is widely accepted in the microeconomic literature that the phenomenon of asymmetric information generates a market failure and that its correction usually leads to a more efficient functioning market.10 In essence, a market with great asymmetry of information does not work efficiently, e.g. debtors may be subsidized, which leads to inaccurate prices and wrong quantities in the market, or buyers may be paying more for goods, or may inefficiently abstain from buying. Thus, at the margin, asymmetries in the quality, quantity, or method of processing of information between parties prevents the conclusion of transactions that at first sight would be mutually beneficial. The phenomenon of asymmetric information is particularly important in the credit market. The nature of credit, which involves a promise of future payment, makes the identification of the profile and the intentions of a potential borrower a crucial factor for estimating the probability of repayment. However, in most cases, such information is not accessible to lenders at a low cost. This asymmetry of information may be responsible for an inefficient allocation of resources with the possibility to generate a process of adverse selection in the credit market. In many countries, especially developing countries, the lack of tools (or their malfunction) to reduce the asymmetry of information in the credit market may result in an equilibrium that would imply higher prices, less credit available, and shorter time limits on credit than would be the case in a scenario of perfect information.11 Traditionally financial institutions try to counteract this asymmetry of information by investing significant resources in the study of potential debtors’ business plans and estimated cash flows and by increasing collateral requirements. However, this strategy is extremely costly and imprecise, thus making loans too expensive to undertake.12 However, the problems caused by asymmetric information extend beyond the stage of credit contract formation. Even once a loan is made, the inability of lenders to control The role played by information in markets has been the focus of a theoretical economic literature in which the works of Jaffe and Russel (1976) and Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) are the main references. 11 This one of the possible scenarios and depends crucially on the amount of information available to creditors. If, for example, the creditors know the quota of bad debtors and of failing credits, then the price may not be higher in the average. There will be less credit to good and more credit to bad debtors. As good creditors use credit more efficiently this will result in a social loss. 12 (Galindo e Miller, p.3) 4 10 borrowers’ actions after they obtain a loan may create moral hazard problems if borrowers adopt behaviors that increase their risk of default (e.g. taking out additional new loans at the same time). Thus, the asymmetry of information between lenders and borrowers with respect to the quality of the profile of the borrowers and the risk of default prevents the market of reaching a socially efficient equilibrium, leading to restricted credit or very high borrowing rates.13 This possible inefficient equilibrium leads market forces, or politicians, to decide to create and operate a mechanism that allows lenders (and borrows) to overcome informational asymmetries. A common organizational arrangement that sometimes is created by market forces and sometimes by state policies is a credit reporting agency.14 It is an institutional response to the problem of asymmetric information in credit markets that tends to be easier to establish than other alternatives, such as, changing complicated regulatory frameworks.15 I will use the term credit reporting agencies (CRA) to refer to any private or public organization that collects positive and negative information on individuals (consumers) and businesses in a country. I am especially interested in a CRA that works with positive data – a positive-CRA – because Brazil, which already has a fully functioning negative-CRA,16 is considering the idea of implementing a fully functioning positiveCRA. To try to confront this problem, on May the 19, 2009, the Brazilian House of Representatives approved the bill 836-E of 2003, which dealt with the establishment of the Positive Consumer Credit Reporting as one measure that would enhance the development of the credit market in Brazil. This bill was vetoed by President Lula that in the next day enacted the Provisory Measure 518 of 12/30/2010. The Provisory Measure 518 created the positive-CRA, but did not regulate it. On May the 09, 2011, the Brazilian House of Representatives approved the Provisory Measure 518. On May the 18, 2011, the senate amended the Provisory Measure that was named bill 12/11 that is a new attempt to create and regulate a positive-CRA in Brazil 14 As pointed by Olegario: “The term “bureau” is used primarily in the U.S. and Canada: elsewhere, the term “registry” is also uses. Although “credit bureau” technically refers to any non-profit or forprofit private organization that collects information on individuals and businesses, in the U.S. the term is used almost exclusively in connection with consumer rather than business credit” … “In the U.S., the history of credit bureaus differs significantly from that of business-to-businesses creditreporting agencies”(Olegario 2002, p.6-7). 15 (Galindo e Miller, 2001, pp.14 and 15) 16 For a survey of all types of negative-CRAs in Brazil and the way they work, see (First_Initiative 2006). 5 13 One of the reasons to create a CRA is that consumer loan default represents a major share of the cost of capital in the credit market, and therefore in the country. A positiveCRA and a negative-CRA may be desirable because the current system of consumers’ databases (if available) is unable to distinguish between the “good” and the “bad” payers. Thus, lenders end up raising interest rates for all consumers to compensate for the default of some debtors. That is, the “good payers” subsidize for the “bad payers.” Accordingly, while a negative-CRA collects and compiles information about borrowers past defaults, or arrears, a positive-CRA collects and compiles positive credit information about borrowers. It handles data concerning not only to the delay or default, but also to the timely payment of obligations by the borrowers. Thus, any “negative” information concerning earlier defaults or delays could be analyzed together with “positive” data about regular timely payments. A positive-CRA would provide therefore a more complete picture of the credit history of each individual and complement the information collected by negative-CRAs. The idea is that positive-CRA may provide more complete information to the lenders about the financial performance of the borrowers, beginning at the time of their inscription in the system.17 In countries where just negative-CRAs exist, the implementation of a positive-CRA could improve the selection of borrowers by the lenders. An idea first introduced by (Pagano and Jappelli 1993) is that CRAs in general – either only with negative, or positive, information or both – help reduce adverse selection by improving the overall pool of borrowers to lenders. This occurs because once credit information about all customers is publicly available, financial institutions can access the quality of non-local potential customers and lend to them with the same level of safet as they do with their local clients. As a result of this, the overall default rate for all loans tends to fall. However, Pagano and Jappelli also note that the net effect of this information spreading on overall lending is ambiguous, since the net effect of the implied increase in lending to new “safe” borrowers minus the possible reduction in lending to risky types is not easily calculated and would depend on further variables related to the lending market in scrutiny. This is similar to the way insurance companies use historical data of a prospective insured, or a potential employer uses past information about a potential employee. 6 17 Some positive sides of a positive-CRA Nonetheless, in principle, the establishment of a positive-CRA may enable a reduction in per-loan costs, thereby opening up new lending opportunities and greater access to credit for some borrowers. This is because when an individual cannot demonstrate her commitment to pay its debts (e.g. through collateral), and there is a large asymmetry of information about their ability to pay, the lenders must rely on inferences about the likelihood of default. With a more comprehensive database on the historical profile of consumers, financial institutions may make fewer demands (e.g. lower initial payment, less collateral, lower interest rates etc.) so that those consumers with good credit history have better access to credit lines. Provided with more information, lenders can better differentiate the risks of potential debtors and offer credit terms in balance with those risks. This may allow financial institutions to identify more easily borrowers with good credit history and charge them interest rates more consistent with their levels of risk. This improved differentiation between “good” and “bad” payers, in turn, may provide a mitigation of the problem of adverse selection in the credit market. In addition, the closer and more accurate supervision of borrowers credit history creates a new kind of collateral – “reputation” collateral, which in turn can help reduce both the problems of adverse selection and moral hazard in credit markets to the extent that borrowers now have a higher stake in maintaining their “positive” evaluation.18,19 Individuals with lower economic means often cannot prove they have a steady source of income or that they own property to use as collateral. A positive-CRA helps people with lower levels of income to signal in a credible and objective manner their historical ability and willingness to repay their obligations. Thus, the credit history can be understood as a “good” on which the State assigns a property right, 20 causing the individual to value it even more. In short, a positive-CRA transforms information into a (Galindo e Miller, p.3) We must acknowledge, however, that even though a system with positive credit information helps to mitigate the moral hazard, an even better system to this end would also make public information about the overall credit extended to each borrower, thus allowing each potential debtor to easily access the level of indebtedness of each potential borrower. This is important since a borrower’s default risk depends on how much of his income is devoted to the payment of debt. If this information is not made available to potential lenders, the borrowers will have an incentive to over-borrow, thus lowering his ability to pay past debts. 20 Nowadays, specific creditors own this right. If the individual is a client in a specific bank, this bank owns his or hers rights, only the bank have information – the individual knows, but cannot use it because cannot prove it – over historical ability and willing to repay of the individual. 7 18 19 commodity that can be “appraised, bought, and sold” by the market (Olegario 2002, p.89), and also transfers to borrowers a title of property over their credit history. The creation of a title of property over individual credit history is a good by itself and gives borrowers incentives to take care of their property so that it may be used in a more efficient way.21 It is not an exaggeration to infer that a title over individuals’ credit history is a measure that creates wealth. Furthermore, if the future access to credit is valuable to the borrower, then she will have an additional incentive not to default on a loan contract because it will damage her future credit. Thus, besides providing the lender with the necessary information to measure risks more precisely, a positive-CRA provides additional incentives for borrowers to use their credit more responsibly. This should also mitigate the problem of moral hazard, since consumers will have greater incentives not to engage in behavior that increases their probability of default.22 This point deserves further elaboration. Contrary to Jappelli and Pagano 2006, I argue that the disciplinary effect of CRAs arises not only from the sharing of negative information, but it is also strengthened by the disclosure of positive information. Jappelli and Pagano claim that a “high-quality borrower will not be concerned about his default being reported to outside banks if they are also told that he is a high-quality client.”23 However insightful, I believe this analysis neglects an important additional point. The sharing of “positive”, in addition to “negative”, data gives the borrower a greater interest in maintaining his positive image. One default only might be enough to stain someone’s image or credit scoring in the short run. In addition, as mentioned above, the sharing of positive information about one’s credit history works as an endowment for the person. So, given the fact that most people tend to weigh losses more heavily than gains (loss aversion), the idea of losing such endowment (that is, a positive image in face of potential debtors) would to provide further disciplinary incentive on borrowers, not less. For a more elaborated explanation on how a title of property protected by the State may stimulate the efficient use of a resource see (Hardin 1968). 22 It should be noted that in countries where there is not a well-developed system of consumer credit reporting, lenders might make the mistake of lending to borrowers who already have other debts (loans) that undertake substantial portion of their income. These errors result in higher costs of credit. Another way of seen the importance of positive-CRAs is highlighted by Galindo and Miller: “Credit registries which collect standardized historical data on borrowers can create a new kind of collateral—reputation collateral—which can help both in reducing problems of adverse selection and moral hazard” (Galindo and Miller 2001, p.3). 23 Jappelli and Pagano 2006 p. 11. 8 21 When analyzing which groups might benefit more from such a credit information sharing system, there is evidence in other countries that shows that younger individuals are a class of borrowers who can greatly benefit from the existence of a positive-CRA (Staten and Cate 2003). At this point it is important to emphasize that the Brazilian bill, for example, provides for the inclusion in the positive-CRA of consumer’s payments of their power bill, water bill, telephone bill, gas bill, etc. This is important because younger individuals, or those who have not had prior access to credit, might be able to create a positive credit history through prompt payment of these bills. Another group that would benefit from a positive-CRA is small businesses. These firms are perhaps the segment of the credit market where the negative impact of asymmetric information is most evident. First, the vast majority of small businesses don’t have independent analysis criteria available either through ratings firms or stock and bond prices. Second, small businesses are very diverse group, thus it is extremely difficult for lenders to identify clear criteria that could constitute successful predictors of default or serve to quantity risk. Further complicating matters, many small business owners mingle their personal finances with those of their company, experience excessive economic volatility, suffer from poor accounting techniques and engage in widespread tax evasion24. All of these negative factors can be addressed, or have their negative effect mitigated, by the use of credit scoring techniques. A further question that regulators must confront is whether to use positive-CRA’s to engage in credit scoring of the individuals registered on their files. The creation of a positive-CRA can be accompanied by positive-CRA using risk analysis on the available data of the borrower. When positive-CRAs rate (potential) borrowers based on their credit history, they can employ statistical models to produce and sell credit scoring services.25 The choice of the variables that will compose the statistical model in many cases is regulated by the legislature or the judiciary. In the case of the Brazilian Draft Law, the regulator required the disclosure of the variables used in the risk analysis, so that the positive-CRA must make public the information it considered in its scoring system. Such regulation is important for transparency and social control of the 24 25 Galindo e Miller, p.3 See (Jappelli and Pagano 2002, p.2022). 9 evaluation methods.26 This risk analysis aims to replace other mechanisms of compiling information about the profile and paying capacity of consumers (such as interviews, credit forms etc.) with a more accurate method based on documented historical consumer behavior. By numerically ranking (potential) borrowers, statistical models used in credit scoring are an important mechanism to help lenders in many credit markets, and the tools of credit scoring are now expanding their influence over lenders’ decisions in mortgage and small business loan markets.27 In fact, in some countries, such as the United States, information models are used for making lists of consumers or companies that are granted pre-approved credit lines (prescreening). By providing fast and cheap access to information about the historical profile and behavior of debtors, the databases will enable better monitoring of the activities of consumers after the loan has been granted. Greater monitoring, in principle, tends to mitigate the problem of moral hazard mentioned above. The experience of specific countries has also shown that the existence of a complete reporting about the payment history of consumers is especially important for those sectors of the population with lower levels of income. For example, a comparison in the United States between access to unsecured credit between the 1970’s, a decade in which there was a major reform in the consumer credit reporting system and the year of 2001, found a growth of almost 70% for the lowest one fifty of the population and 30% for the second fifth of lower levels of income, respectively, in face of a growth of approximately 10% for the remaining three fifths having higher levels of income.28 Thus, a system of consumer credit reporting seems to improve access to credit and reduce firms’ financial constraints, while also allowing lower economic classes and younger consumers to have more and better access to credit, insurance and other financial services. Such access would be based only on their historical bill paying profiles, and not based on ownership of assets that could serve as collateral, or on prior credit relationships, as occurs with consumers with higher levels of income. There is the possibility, however, of a marked desire to use variables in the statistical model of evaluation of credit scoring that may go against social desire and the legislature or the judiciary will have to intervene in this issue. 27 See (Galindo and Miller 2001, p.2). 28 See (Staten and Cate 2003). 10 26 Some negative sides of a positive-CRA Some critics have argued those modern credit scoring models applied today are biased against minorities and women. In certain cultures the argument goes, minorities are more likely to take loans and to take trade credit from community groups and local members that provide credit based on borrowers’ "character" (a cultural idea), rather than on any other indicators of credit worthiness control. 29 These local loans tend not to be reported to positive-CRAs, thus create no credit history. Positive- CRAs may be also biased against women. As it is true in some countries, women tend to be a coadjutant in the financial lives of the couple. In these countries, usually most of the credit history of the couple is constructed in the husband’s name.30 To protect against such biases, a positive-CRA should expressly provide rules for the information stored in the credit registries. The regulator ex ante, or the judiciary ex post, must supervise what type of information is collected by the positive-CRA. In the case of the Brazilian Draft Law, the regulator determined that the information collected, stored and processed in positive-CRAs should be objective, clear, accurate and easily understood. It also forbid collection of any information that does not have a direct relationship with risk analysis of the debtor, including social and ethnic origin, health and sexual orientation, political, religious, and personal beliefs. This type of regulation is necessary to avoid discrimination against minorities and woman. Furthermore, the use of any information by the positive-CRAs for other purposes than credit risk analysis (e.g. marketing, direct mail, search marketing etc.) should be permitted only after the express authorization of the registered consumer. Respecting these and other restrictions, potential lenders could use the information to complement other data that they already have about the reliability of the potential borrower to make decisions about borrowers` financial stability and their consequent ability and willingness to repay the debt. As an example, such information may be used to make decisions about loan granting, price, deadline, and other credit conditions. Furthermore, the overlap of mechanisms between a full functioning positive-CRA and other systems that partially collect and provide positive credit consumer history needs to be critically discussed. A positive-CRA may complement and refine an existing system For a deep explanation and more examples on how positive-CRA may contain hidden biases against minorities and women, see (Olegario 2002, p.40-41) 30 See note 29 11 29 of credit information. For example, the Credit Information System of the Brazilian Central Bank (Sistema de Informações de Crédito do Banco Central – “SCR”) is a tool for supervision of the banking sector The SCR is one of the main instruments used by the Central Bank to monitor the credit portfolios of financial institutions. It also gathers data on borrowers’ credit behavior with regard to their obligations incurred in the financial system, which is filed monthly by the financial institutions. Only customers whose total obligations are equal to, or greater than, R$ 5,000.00 (~ US$ 2,500.00) are identified.31 With this limit, the SCR does not reach the financial arrangements of the classes C, D, and E32. This weakness of the system may be alleviated by a positiveCRA. The SCR does not fully function as a positive-CRA; its main function is to assist banking supervision activities. Although its main function is to assist in banking supervision, SCR provides some positive credit information to the market. It provides borrowers’ credit history information to the regulated financial institutions that feed its database, but not to other financial institutions that do not provide data to SCR. In situations like this, a fully functioning positive-CRA could offer these services to the credit market as a whole, so that all lenders would have access to this information.33 The next section focuses on both existing analyses and new insights into a cost benefit analysis of positive-CRA. III – Limiting Features of Consumer Credit Reporting The creation of a fully functioning CRA may generate two types of effects. The first effect, as mentioned above, is that it reduces the asymmetry of information between lenders and borrowers with a consequent positive impact on adverse selection and moral hazard on credit markets. The second effect could be to invigorate competition between lenders, reducing the rents that financial institutions could otherwise extract from their See (First_Initiative 2006, p.12). “The Brazilian Economic Classification Criterion (CCEB) is an instrument of economic segmentation that uses a survey of household characteristics to differentiate the population. The criterion assigns points according to each household characteristic and performs the sum of these points. In the sequence, there is a match between the test score ranges and levels of economic status defined by A1, A2, B1, B2, C1 C2, D, E” – Source ABEP. (http://www.abep.org/novo/). Last accessed 04/07/2011. 33 For a complete survey of the many types of negative and positive credit reporting system available in Brazil and their functioning and coverage see (First_Initiative 2006) 12 31 32 customers.34 The Brazilian Draft Law assumes that the creation of a positive-CRA is an additional measure to enhance credit market competition and that this is one of the most important characteristics of the creation of a fully functional positive-CRA. By reducing the cost of evaluating the risks of consumers, a database of “positive” and “negative” information reduces the barriers in the credit market, facilitating the entry of new competitors. The fact that the credit registries do not have such historical “positive” information acts as an entry barrier because gathering this kind of information from potential new costumers, that is, people who do not yet have any kind of relation with potential entrants, can be extremely costly. To the extent that the incumbent financial institutions already possess such information from their customers, they hold an “information monopoly” on the information they possess about their customers, and because of the resulting high entry costs for other lenders, they are able to extract rents from their customers. In this system, without the implementation of consumer credit reporting, potential entrants do not have access to important information. Therefore, they cannot offer financial products and services at competitive prices and conditions. Indeed, the potential to increase competition is one of the most important factors for an effective reduction of credit prices because even reducing the costs of evaluating the risk of consumers and increasing the availability of such data at a lower cost does not, by itself, determine that the cost savings will necessarily be passed on to consumers. This will only incur as a result of increased competition in the provision of credit.35 This point deserves further qualification. Even if we acknowledge that the lack of positive information about borrowers indeed constitutes a barrier to entry in the financial sector, this may not be the only barrier. In fact, it may not even be the most important one. Given this, it might be the case that the creation of positive CRAs will not reduce sufficiently the barriers to entry to foster a higher level of competition in the sector so that the prices of loans to costumers fall. However, we cannot resolve this issue solely from theory as it is ultimately an empirical question. Another relevant issue regarding a positive-CRA is the question of why incumbent financial institutions have not created a similar private system? One possible answer is 34 35 See (Padilla and Pagano 1997, p. 206) See (Stiglitz and Weiss 1981) and (Pagano and Jappelli 1993) 13 that the financial information that financial institutions already hold about their customers provides them with such a “similar system.” Given this, one might argue that the creation of positive-CRA would conflict with the existing private arrangements. There are other possible answers to the question of why incumbent financial institutions have not created a similar private system. First, the financial institutions hold all relevant information about borrowers so the creation of positive CRA wouldn’t change much for them.36 Second, one might argue that the private sector still has not created such system because it would constitute a form of “public good.” Consequently, its creators would not be able to individually benefit from its creation, which, in turn, would dilute individual incentives to create such system in the first place.37 Furthermore, even if a positive-CRA can provide a more efficient equilibrium in the credit market, there are other obstacles to its creation. Regulators need to determine if borrowers must sign an authorization to be conscripted into a positive-CRAs – an opt in clause, or if borrowers must require withdraw from the registry – an opt out clause.38 Another option for regulators is to allow borrowers to choose to disclose their entire history or just their risk analysis. In fact, there is an incentive for most consumers to allow the disclosure both their history and risk analysis. First, those consumers with an excellent payment history would have a strong incentive to allow his or her inclusion on the credit registries, because they could, therefore, be differentiated from consumers with “worst” history, and thus have access to more credit at better conditions. In turn, those consumers with very good, but not great, historical records would also realize that they would be better off if they allow their inclusion because, in the same way, they could differentiate themselves from consumers with an average history. Following this reasoning, the consumers with average history also have incentives to allow her inclusion, and so on, so that only those consumers with a “bad” history do not allow his or her inclusion, because they would gain nothing from doing it. These last consumers This may be an exaggeration. The creation of a positive-CRA may reduce entry barriers and be a good in itself. 37 But it seems relatively easy to private agents to create a system that could prevent others from accessing it and then charging the members for the use, thus preventing the system to hold the characteristics of a public good. 38 The Brazilian draft law approved by the House of Representatives regulated this issue with an opt in clause. Brazilians’ borrowers must sign in an authorization in order to be scripted in the positive credit registry. 14 36 are only differentiated from consumers with a “very bad” history by the fact that, perhaps, these already are enrolled in the existing negative-CRAs, in the case of Brazil in the Sistema de Proteção ao Crédito – SPC or SERASA.39 Thus, the device that makes the inclusion in the credit registries a voluntary registration can actually become mandatory. Even if in theory it seems to give the borrower the option, in practice it ultimately forces him to sign up or be qualified as a holder of a “bad” payment history.40 If the regulator sets as the default option the opt in clause, and borrowers need to give their consent to be included in the positive-CRA’ database, the regulator will also need to analyze what would be the consequences of the positive-CRA for those consumers with a payment history better than “bad”, that do not enroll in the positive-CRA’s database. These borrowers, in principle, would be confused with those borrowers with a “bad” history, since they would not have strong incentives to enroll.41 The fact is that those borrowers that did not enroll in the credit reporting, in principle, would bear the worst credit conditions (i.e. higher interest rates, shorter deadlines, and fewer resources available). To understand how SPC and SERASA work see (First_Initiative 2006, p.12). “Conventional rational-choice theory is challenged from the opposite direction by game theory. Traditional economics generally assumed (except when speculating about cartel behavior, and in a few other examples) that people made decisions without considering other people’s reactions. If the price of some product falls, consumers buy more without worrying that by doing so they may cause the price to rise again. The reason they do not worry is that the effect of each consumer’s decision on the price is likely to be negligible (the consumer is a “price taker”), while the costs to the consumers of coordinating their action would be prohibitive… Federal law forbids colleges to disclose a student’s transcript to a prospective employer or another educational institution without the student’s permission. Such permission is almost never refused. Game theory can help us see why without our having to assume hyperrationality. If no student gave permission, an employer considering a job application from a college student would assume that the student had average grades – what else could he assume? Students with above-average grades would be hurt by this assumption, so they would begin giving permission to their schools to release their transcripts. Eventually all students with grades above the midpoint would grant such permission. So now when an employer received an application from a student who had not released his transcript, the employer would assume that the student was in the middle of the lower half of the grade-point distribution, because everyone in the upper half would have revealed his grades. So every student in the third quartile (that is, in the upper half of the lower half of the grade distribution) would be disadvantaged by nondisclosure and would reveal his grades. Eventually only the student with the very lowest grades would have nothing to gain from disclosure – and his failure to disclose would reveal his rank as unerringly as if he had disclosed it. Simple game theory thus shows why the law protecting the privacy of transcripts has been ineffective. The example illustrates what game theorists call a “pooling equilibrium,” in which (in contrast to a “separating equilibrium”) strategic behavior prevents people with different preferences from acing differently. The reasoning process required to achieve a pooling equilibrium in the student-transcript case is not so elaborate as to require hyperrationality” (Posner 2007). 41 This is one type of false-negative that will be discussed below. 15 39 40 This point deserves attention because, in practice, some borrowers, even with a “good” history of payment, might not enroll in the credit reporting, even if it would generate future net benefits. In fact, people usually have, for different reasons, a tendency to maintain their current situation (status quo bias).42 This can occur, for example, because of a mere lack of attention resulting in bad choices. Especially in situations where the benefits may not be clear (as in the case of enrolling in credit reporting) people can simply opt not to choose one option that, theoretically, would bring them a greater expected net benefit. Accordingly, a possible regulatory alternative would be that individuals are automatically enrolled in the positive-CRA and their risk analysis disclosure unless they affirmatively choose not to be – an opt out clause. That is, regardless of any authorization, the borrower would already be enrolled in the positive-CRA and her risk analysis disseminated for the financial institutions interested. The borrower would have the choice to be excluded of the credit registries and of the risk analysis, but she should expressly communicate her choice to the positive-CRA or to any governmental authority. This should be made possible in a quick, easy, and free manner. This scenario would tend to reduce the number of borrowers with “good” history that are not enrolled in the credit reporting and enable better credit conditions to this class of consumers. As well by keeping for the consumer the option to be excluded from credit reporting at a low cost, it would maintain their right to privacy. Another point that deserves attention in a proposal to create a positive-CRA is the assumption that the correction of the asymmetry of information will promote a more efficient equilibrium in the credit market of the country. It should be recalled that a market is composed of many elements that form an intricate network of causalities. Repositioning any of its elements may not ensure efficiency in the resulting new equilibrium.43 See (Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988). This concept is linked to the “Theory of Second Best”, which, briefly, assumes that in a system with several variables, for some reason, one (or several) of these variables can not take the value for that the outcome imagined as “best” option be observed. This theory assumes that in some situations, for the “second best” option be achieved it would be necessary for other variables, other than the first, assume different values from those that would be needed to obtain the “first best option.” See, (Lipsey and Lancaster 1956). 16 42 43 CRAs will impact informal lending and retail shops. This is important since both players might be excluded from the information sharing system created by the CRAs and, thus, not benefit from the mitigation in the asymmetry of information and other advantages abovementioned. To counter this limitation, a CRAs’ system can be institutionally designed to provide access by such important players to credit information disclosures. In addition, adding such players to the credit sharing system could also benefit the financial institutions. A requirement that informal lending and retail shops provide information about their customers could reduce the asymmetry of information for the whole market. This is more important when the share of informal lending is bigger relative to the overall level of lending in the country, as is the case of most developing countries. As for retail shops, their inclusion is likely to benefit more developed countries with high levels of consumer debt, as is the case of the United States. There is a possible conflict between the creation of a positive-CRA and personal privacy. When we lose part of our privacy, do we also lose fractions of our integrity, or personhood, or honor, or dignity, or liberty, or humanity? “The concept of privacy,” writes Whitman, “is very embarrassingly difficult to define.”44 The creation and implementation of a positive-CRA implies that merchants, banks and other types of creditors will be allowed to access the credit record of their customers. 45 For these customers, who may have never failed to pay their debts, isn’t it a violation of privacy? People from different countries, or even from different parts of the same country, may profoundly disagree over this aspect of the protection of consumer data.46 Although I recognize the importance of the debate that surrounds the concept of privacy, I do not have the intention – or pretension – to define the meaning of the concept of privacy. I just want to call the attention to the complexity of the debate. For 44 See (Whitman 2004, p. 1153) Banks and other types of creditors will be allowed to access and will have the obligation to inform the financial characteristics of their customers to the positive-CRA. 46 It is widely debated in “privacy” literature that individuals from different countries – i.e. United States, France, Germany, and others – have different feelings about the concept of privacy and about how the government must treat or regulate consumer credit reporting and other consumer data. See (Whitman2004). In the Brazilian case, due to the continental size of the country and diversity of people’s culture, individuals from different parts of the country may have very different opinions about credit reporting and other consumer data, and may differently take advantage or disadvantage of the creation and implementation of positive-CRA. 17 45 the purpose of this article I will treat privacy, like Stigler has done, as a matter of public policy.47 The creation of a positive-CRA is a policy choice that directly affects the acquisition and control of information about people. It is essentially the government trying to regulate the amount of information that each individual discloses in order to be part of society, and by compelling personal disclosure such regulation, at least theoretically, weakens individual privacy protection. In addition to the attendant loss of privacy that individuals may incur, there are costs suffered by individuals that have false negative information about them appearing in a positive-CRA. A public policy that creates a positive-CRA must acknowledge that information about individuals is frequently claimed to be mistaken or misused.48 The major problem in this situation is that an individual that has false negative information inserted to his credit history may value the correction of this error much more than the positive-CRA organization would be willing to spend to correct it. IV – Examining Privacy Costs Positive-CRA versus Privacy In this final section, I used an empirical approach to try to better understand the link between privacy and better credit conditions for Brazilians’ consumers. To begin with, let’s assume a perfect world in which a positive-CRA provides a more efficient equilibrium in the credit market, so that more and cheaper credit is available in the market. If this could happen, how much privacy are individuals willing to give up for these better credit conditions? This is the empirical question that this exercise will try to answer. Survey A sample of 447 subjects participated in the study.49 Their average age was 34 years, the youngest being 18 years old and the oldest 74 years old. 56,28% of the subjects were See (Stigler 1980) See (Stigler 1980, p.624-625) 49 The survey was applied from December 9 to 15 of 2010. 47 48 18 from class A and B, and 41,93% of subjects were from class C. There were no class E individuals in the sample.50 The survey instrument collected the following demographic details on the subjects: gender; age; occupation; and years of school. The survey instrument was comprised of 33 questions with different number of alternatives in each question. Subjects were recruited from visitors at two different shopping malls in city of Rio de Janeiro. We analyzed the results of the survey’s questions to provide some indications on the subjects’ preferences. We also made tables and charts to help to evaluate these results. Questions Asked and Information Collected While a large amount of information was gathered, we summarize only the most important pieces in this paper. In the materials below, we first state the question asked and then summarize the information collected. First, questions 22 and 23 we measure if the Brazilian consumer were informed of the creation and the characteristic of the positive-CRA. In question 22 the survey instrument asked the following question to the subject: In Brazil we have the negative-CRA, which is a public record of bad credit reputation. In other words, if a consumer does not pay his debts his name is registered in the record. Did you know that? 99.95% of the subjects answered they knew about the negative-CRA. The next question asked to the subject: The Brazilian government has created a positive-CRA, which is different from the negative-CRA: instead of listing only consumers who did not pay their bills, the new registry will list all consumers and classify them as a "great", "good" or "regular" payer. The new registry will be consulted by financial institutions every time the consumer attempts to take a loan. Did you know or ever heard about it? Only 43% of the subjects had already heard about positiveCRA. Table 1 below summarizes this information. ________________________________________________________________________________ Descriptive Data. Table 1 Table 1 presents descriptive statistic. It describes answer from questions 22 and 23. 50 See note 32 19 Yes No Question 22 Number % 444 99,55% 2 0,45% Question 23 Number % 192 43,05% 254 56,95% The charts below summarize the questions asked and information collected in questions 24, 25, 26 and 28. The answers to question 24 – show that 58% of the subjects prefer privacy over easier and cheaper credit. In response to question 25, 62,19% of the subjects said they would not take the risk of being classified in a wrong category (i.e., instead of being classified as excellent you are classified as good payer) in order to have better access to cheaper credit. Question 26 responses indicate that more than 86% of the subjects believe that consumers should be consulted before having their name included (registered) in the positive-CRA. In other words, inclusion should not be an automatic – opt in clause. This result indicates that the protection of privacy has a clearly high correlation with the desire to not having one’s name included in a positiveCRA without giving consent. We next asked in question 28, if the subject preferred the positive-CRA to be under the control of a government branch, or under the control of a private institution. We found that 58% preferred a public one. We can infer that the fear of the loss of privacy makes the subject more confident in having their data collect by, and distributed by, the government rather than with a private company. Our next set of questions focused on borrowing behavior. Although more than 80% of the respondents think that credit is a positive thing to have (question 16), and more than 70% of the subjects think it is easy to get 20 credit (question 13), 77,4% of the subjects gave for not borrowing money in the last 12 months (question 11). The three main reasons for subjects not borrow money in the last 12 months were: the lack of need, the fear of getting in debt and the high costs of borrowing (question 12). The chart below illustrates the breakout of the responses. We can link the result in question 24. If people think they do not need money, why would they give up some privacy or risk being wrongly classified by the positive-CRA? In this case, respondents that do not need a loan are unwilling to sacrifice their privacy in order to be registered by the positive-CRA. Moreover, the results discussed above can be related to the income of the class that the subject belongs. If the subject belongs to the higher class, it will be easier to her to have access to credit and this will make it less important to be registered with a positive-CRA with the resulting loss of privacy. Econometric Analysis In this section, I use regression analysis in an effort to determine how subjects with different demographic details and characteristics (age, gender, and years of education) reacted with privacy losses. Recall from the previous section that there are two questions that address directly to privacy: question 25, which examined the tradeoff between access to cheaper credit and the risk of incorrect information being created at a positive-CRA, and question 26, which asked about whether consumers should be automatically included in a positive-CRA or have to opt in. We tested to find out if age, gender, and years of education were statistically significant determinants of how respondents answered these questions. 21 Equation question 25: Q25 = C + aQ7sav + bQ11 + cQ13e + dQ15cw + eQ15pwn + fQ15pw + gQ17 + hQ27 Label Q25 Q7sav Q11 Q13e Q15cw Q15pwn Q15pw Q17 Q27 Parameter C a b c d e f g h Meaning Consumer (subject) will not want to take the risk of being incorrectly classified Consumer (subject) has savings Consumer (subject) borrowed money in the last 12 months Consumer (subject) thinks it is already easy to borrow money Consumer (subject) will certainly borrow money in the next 12 months Consumer (subject) will not probably borrow money in the next 12 months Consumer (subject) will probably borrow money in the next 12 months Consumer (subject) had a credit request denied Consumer (subject) wants to be part of Positive-CRA Value 0.526 0.231 -0.14 0.789 -0.468 -0.084 -0.210 -0.150 -0.012 Prob. 0.000 0.000 0.016 0.082 0.000 0.068 0.022 0.004 0.025 Equation question 26 Q26 = C + aQ15cwn + bQ15cw + cQ15pwn + dQ15pw + eQ31 Label Q26 Q15cwn Q15cw Q15pwn Q15pw Q31 Parameter C a b c d e Meaning Consumers (subject) thinks they have to be asked prior to be included in Positive-CRA Consumer (subject) will certainly not borrow money in the next 12 months Consumer (subject) will certainly borrow money in the next 12 months Consumer (subject) will not probably borrow money in the next 12 months Consumer (subject) will probably borrow money in the next 12 months Consumer (subject) had already been registered in negative-CRA Value 0.999 -0.089 -0.378 -0.145 -0.352 0.002 Prob. 0.000 0.000 0.010 0.082 0.000 0.001 22 The results show that if the subject has savings,51 this raises the probability by 23,1% that subject will not want to take the risk of being incorrectly classified. In other words, the subject does not want to be registered at a positive-CRA, and may not want one to even be created if they cannot opt out. Furthermore, if it is already easy to the subject – in their own perception – to borrow money52, this increases the probability in 7,8% that she will not want to take the risk of being incorrectly classified. Here again, these subjects do not want to be registered at a positive-CRA nor even want the creation of a positive-CRA. Conversely, if the subject borrowed money in the last 12 months53, this raises the probability by 13,9% that she would like to have access to cheaper money and therefore is more willing to take the risk of being incorrectly classified. If the subject thinks she will certainly borrow money in next 12 months,54 this raises the probability by 46,7% that she will want to take the risk of being incorrectly classified. In a third variation, we find that if a person already had a credit request denied55 then they are more likely to be interested in cheaper credit which lowers the probability by 14,9% that the subject wants to take the risk of being incorrectly classified. All these coefficients are significant at the 10% level and the majority of them are significant at 5% level. In the second set of regressions, we examined the issue of opt in versus opt out provisions for the positive-CRA. The results showed that if the subject had already been registered in a negative-CRA,56 then this increases the probability by less than 1% that she will want an opt out positive-CRA. Question 7: “Do you have a…”. Answers: 85.46% have checking account; 82.77% have saving account; 83.67% have credit card; and 46.76% have store/supermarket card. 52 Question 13: “For you, getting access to credit is…” Answers: 2.47% of subjects think it is Very hard; 17.94% Hard; 59,87%Easy; 12.11%Very easy; and 7.62% do not know. 53 Question 11: “Did you borrow money in the last 12 months? It can be a loan, a purchase installment plan, a house financing plan or any other kind of borrowing”. Answers: 22.6% said Yes, while 77.4% said No. 54 Question 15: “Thinking about the next 12 months, would you say…”Answers: 43.18% of subjects certainly will; 44.07% probably will; 8.28% probably will not; 2.46% certainly will not; and 2.01% do not know they will take a loan. 55 Question 17: “Have you ever have a loan request denied?”. Answers: 26.17% answered affirmatively, whereas 73.83%, negatively. 56 This inference – good debtor – is based on the answers of questions 13 (showed above) and 31. Question 31: “Have you ever had your name included in Negative-CRA?” Answers: 34.4% of subjects said Yes, while 65.6% did not. 23 51 For all the other tested variables the probabilities were negative. For example, if the subject is not sure she will borrow money in the next 12 months, this raises the probability by 37,8% that she prefers an opt in positive-CRA. Similarly if the subject thinks she will probably not borrow money in the next 12 months, this raises the probability by 35,1% that she prefers an opt in positive-CRA. These results generally indicate that subjects prefer an opt in positive-CRA. The results also indicate that privacy is more important than positive-CRA even thought it could be beneficial to all. The coefficients are all significant at the 1% level. V – Conclusion The issues discussed herein are important and do not have simple answers. Moreover, empirical research on the impact of credit reporting agencies on credit markets is scarce. However, the few comprehensive empirical studies available suggest not only a growth and international diffusion of CRAs, but also that the existence of credit registries has a significant positive impact over the amount of credit available in a given economy (relative to GNP) and a negative impact on defaults.57 The positive impact of CRAs was identified regardless of the significant heterogeneity in the operating rules of the CRAs in different countries. Standardized data about the historical profile of borrowers, in principle, may help reduce costs for the granting of credit. However, this measure alone is likely to be insufficient to allow and encourage the development of the credit market in a country. Its positive impact will depend on the increase of competition in the sector. Even though the creation and the implementation of the positive credit registry may reduce the barriers to entry in the credit market, this may be insufficient to strengthen competition among lenders in a way that guarantees that consumers will face lower interest rates, that there will be an increase in the amount of available credit and overall better credit conditions. Even though a positive credit registry may bring all improvements in the 57 See (Jappelli and Pagano, 1999) and (Galindo e Miller, 2001) 24 credit market that the theory highlights, there may be other costs it creates, such as taking away some privacy rights for those included in it. References: Akerlof, G. A. (1970). "The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 84 (3): 488-500. First_Initiative (2006). Credit and Loan Reporting Systems in Brazil, Western Hemisphere Credit And Loan Reporting Initiative. Centre For Latin American Monetary Studies. First Initiative. The World Bank. Galindo, A. and M. Miller (2001). "Can Credit Registries Reduce Credit Constraints? Empirical Evidence on the Role of Credit Registries in Firm Investment Decisions." Inter-American Development Bank. Jaffe, D. M. and T. Russell ( 1976). "Imperfect Information and Credit Rationing." Quarterly Journal of Economics 90(Nov. 1976): 651-66. Jappelli, T. and M. Pagano (2002). "Information sharing, lending and defaults: Crosscountry evidence." Journal of Banking & Finance (26): 2017-2045. Jappelli, T. and M. Pagano (2006). Role of Effects of Credit Information Sharing. The Economics of consumer credit. G. Bertola, R. Disney and C. Grant. Cambridge, The MIT Press. Olegario, R. (2002) "Credit-Reporting Agencies: Their Historical Roots, Current Status, and Role in Market Development." World Bank Volume, DOI: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDR2002/resources/2429_olegario Padilla, A. J. and M. Pagano (1997). "Endogenous Communication Among Lenders and Entrepreneurial Incentives." The Review of Financial Studies 10(1 ): 205-236. Pagano, M. and T. Jappelli (1993). "Information Sharing in Credit Markets." The Journal of Finance 48(5): 1693-1718. Pinheiro, A. C. and A. Moura (2001). "Segmentation and the Use of Information in Brazilian Credit Markets." This paper was written as part of the World Bank´s research project on “Credit Information in Latin America”. http://www1.worldbank.org/finance/assets/images/castelar-moura_2-1901_Credit_Text_10.pdf Posner, R. A. (2007). Economic Analysis of Law, New York: Aspen Publishers. Samuelson, W. and R. Zeckhauser (1988). "Status Quo Bias in Decision Making." Journal of Risk & Uncertainty 1. Staten, M. E. and F. H. Cate (2003). "The Impact of National Credit Reporting Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act: the Risk of New Restrictions and State Regulation." Credit Research Center Working Paper nº 67, 2003. Available at www.ftc.gov/bcp/workshops/infoflows/statements/cate02.pdf. Stigler, G. J. (1980). "An Introduction to Privacy in Economics and Politics." The Journal of Legal Studies 9 (4): 623-644. Stiglitz, J. E. and A. Weiss (1981). "Credit Rationing in Markets with Imperfect Information." The American Economic Review 71(3): 393-410. Whitman, J. Q. (2004). "The Two Western Cultures of Privacy: Dignity versus Liberty." The Yale Law Journal 113(6): 1151-1221. 25