Evaluation, Perspectives and Effects on Small Firm Credit

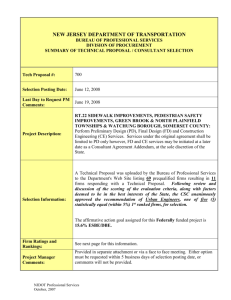

advertisement