ABSTRACT

advertisement

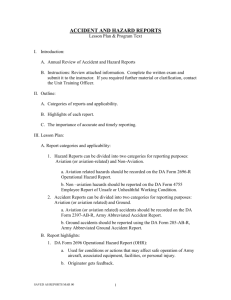

A Historical Review of the Technical and Social Conflicts OF Aviation Accident Investigations BACKGROUND OF THE PAPER This paper is an updated report on a study of the conflicts that exist between the technical and social aspects of the aviation accident investigation process in the US. These same conflicts may well exist in other countries but that is not addressed in this study. While the concept for such a study dates back to the early 1980s, it was not until 1991 that work on the project began in earnest. The author, Dr. Michael K. Hynes undertook this research to complete his Doctoral Dissertation, Technical and Social Conflicts of Aviation Accident Investigations, which was published and presented at Oklahoma State University in 1995. While his research was in progress, Hynes furnished drafts to various parties, including the former National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Chairman, Jim Hall. Perhaps the now famous December, 1999, $400,000 Rand Report, commissioned by Chairman Hall in June of 1998, which was stated to be a “self-critical examination of the (NTSB) agency” (p. v), was inspired by Hynes’ activities, findings, and letters to Chairman Hall. In 1995, the research was updated and its findings were published and presented at the International Society of Air Safety Investigators’ October, 2000 seminar held in Dublin, Ireland. The study was updated again in 2005 in response to comments by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners “that their was a need for change”. In response to public demands, the US government made major changes to the aviation accident investigation process and charged the NTSB with the task of meeting the “social” needs of the public after major aviation accidents. NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners’ recent remarks to the aviation community was the first time a public discussion of the existing conflicts between the Technical and Social Conflicts of Aviation Accident Investigations was undertaken by a government official. Her remarks, which confirm some of the findings of this research, were considered a justification of reviewing, updating, and presenting the material contained herein. SUMMARY The aviation and legal communities, as well as the public and government agencies (specifically the FAA and NTSB), should join together to more openly discuss the concerns mentioned by Chairman Engleman Conners. These discussions should result in the adoption of one or more of the recommendations of this research. These groups can then request that new policies or laws be implemented to address the conflicts mentioned. This should help to achieve high quality aviation accident 1 investigations that result in valid, complete, timely, and useful accident reports, which are reasonable expectations of the public. As a result of several recent major air crashes, public confidence in the air transportation system has been lessened. Several times in the past, similar events resulted in major changes in the manner in which the US government has regulated aviation. The “first” FAA was created in response to a mid-air collision between two Air Carriers, and likewise the “second FAA” was also created in response to a mid-air collision some twenty years later. Again, a series of recent aviation accidents may be perceived by the public as an indication of the need for another change in the manner aviation is regulated and the way aviation accident investigations are conducted. Following the recommendations of this study would add to the safety of the US air transportation system and help restore the public’s confidence in this mode of travel. Some of the billions of dollars in the Airway Trust Fund could be utilized to fund these changes at no additional cost to the taxpayers or the aviation industry. As stated in the Rand report, “While the tenets upon which the NTSB was originally created remain sound, new approaches outlined in the recommendations are necessary to meet the demands of a more complex aviation system” (page xv). “Safer Skies Require Mindset Change” (Duke, 1999, p. 110). Well known and respected former CAA aviation accident investigator C. O. Miller, in his in-depth analysis of the Rand report, agreed with many of the Rand Report’s findings (2000, p. 6). The conclusions and recommendations of the Rand Report and Miller’s comments, confirmed the findings of Hynes’ 1995 research which was updated in late 2000 and again in January, 2005. However, both Miller and Hynes felt the Rand report failed to address many issues which are stated herein and also recently mentioned by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners. As it was written several thousand years ago in the Old Testament, "Make justice your aim: redress the wronged, hear the orphan's plea, defend the widow" (Isaiah I, 17). Such a profound obligation still holds true and should be applicable to the social aspects of an aviation accident process. The adoption of one or more of the suggested recommendations of this research would help to accomplish this ancient but still valid request. INTRODUCTION The act of "flying" is an unusual combination of physical and physiological sciences which must be understood and followed to maintain an acceptable level of safety. Since the days of the first flights, aircraft accident investigation has played an important role in the development of the art, science, and mechanics of aviation (Dorman, 1976). In the early years of aviation, 1903 through the mid 1930s, aircraft crashes were fairly common and seemed to be an acceptable and necessary part of the development of aviation (Walsh, 1975). When crashes occurred, the early inventors were anxious to learn what had happened, so that their next efforts at flying might not end in a similar fashion. Material failures were the most common causes of accidents, but the human factor, the pilot, very often played a critical role in determining the likelihood of accomplishing a successful flight (Josephy, 1962). 2 The early flights of the Wright Brothers and others were measured in seconds. The altitudes they reached were eight to ten feet and their speeds were usually less than 20 miles per hour (Vivan, 1921). Under these circumstances, most crashes did not result in any broken bones, only broken aircraft, broken hopes, and sometimes broken pride. It was not until 1908, when US Army Lt. Selfridge was killed at Ft. Myer, VA (USA), that a death occurred due to a powered aircraft accident. This event resulted in the first formal US aviation accident investigation. The investigation process took only about six hours to complete (Squier, 1908). Because these early aviation accidents did not involve "the public," there was little interest in accident investigation outside the immediate aviation community. As time went by, aviation in America grew, and the post World War One barnstorming age brought the magic of flight to thousands of people in America (Ward, 1953). Unfortunately, some of these flights ended in tragic accidents, with innocent non-aviators being injured or killed. These accidents resulted in public demand for safer aircraft, pilots and some form of government control over all aviation activities. This resulted in the adoption of “aviation laws” or regulations by various States. As early as 1911, the State of Connecticut passed the first aviation laws. Massachusetts soon followed and within five years approximately 25 states had passed some form of aviation regulation. It was obvious to various legal scholars that regulating aviation on a state-bystate basis was not suitable for an activity as complex as flying. Gov. Baldwin of Connecticut requested the American Bar Association (ABA) to formulate and promote some form of proposed air regulations or laws at a “national” level. It was not until almost ten years later, that the ABA, at their 1921 annual convention held in Cheyenne, WY, adopted a set of proposed “national” laws for aviation. It then took Congress five years of discussion and debate to adopt The Air Commerce Act of 1926, the first national or federal regulation of aviation in the United States. Also required were changes to America’s justice system in order to resolve the many new legal issues that aviation activities created. While the first “aviation case” in America took place in the early 1800’s (Guille v. Swan, New York Supreme Court 1806/1823, [19 Johnson, 381]), the courts had no experience dealing with the complex nature of powered aircraft. When courts were asked to deal with litigation that was undertaken related to aviation mishaps and accidents, there were no laws, administrative regulations, or history of “case law” to guide the court. When aviation accidents took place and the public sought compensation for its losses, they found a void in the laws that should have been protecting them from this new science of flight (McNair, 1930). This was the foundation for the support of new laws (Forlow, Hotchkiss, Knauth, and Miles, 1929) to govern “these magnificent men and their flying machines”. As mentioned earlier, in response to industry and public requests, the first aviation laws on a national level in the US were enacted in 1926 (Air Commerce Act). Soon afterwards, official government investigations of non-military aviation accidents began to take place (Young, 1931). The initial and primary purpose of the aviation accident investigation process was to prevent future accidents by learning as much as possible about each accident that had occurred (Dorman). 3 By the late 1930s, aviation was beginning to mature, and the skill levels of aircraft accident investigators were also being perfected (Dorman). As stated in the Civil Aeronautics Administration's (CAA) 1953 manual, Aircraft Design Through Service Experience, much of the development of air travel, "is a result of the lessons learned by these investigators from previous accidents" (p. iii). At the end of World War Two, the aviation industry had reached a level of design and manufacturing that could produce the aircraft, supporting hardware, facilities, and infrastructure needed for a modern air transportation system. With the advent of the jet age, the safety level of air travel reached a point far above what had previously taken place. As stated in the Rand Report, “Safety in air transportation is, therefore, a matter of profound national importance” (p. v). This belief is shared by most nations throughout the world. Considering the high frequency rate at which aircraft took off and landed, air travel had certainly become a very safe means of transportation (Mathews, 1995). The basis for this level of safety, at least in the US, was acquired from the lessons learned during government accident investigations conducted ever since the mid 1920s when the Civil Aeronautics Board was formed to investigate and report on the cause or causes of aviation accidents (Miller, 1994). Background of the Problem As the aviation industry matured, its safety record reached a level where the public began to accept traveling in an airplane as a normal activity that had high national value (Truman, 1947). From the early 1960s, when less than 20 percent of the public had flown, (Hynes, 1967) to the mid 1990s, when over 75 percent of the American adult public had flown, millions of take offs and landings were being made without incident (Pena, 1995, p. 16). “By the late 1900s, air travel had become a consumer product” (Hynes, 2000, p. 2). Aviation accidents, at least those of major airlines, were so infrequent that they were considered “random events" by some government officials and NTSB accident investigators (Schleede, 1992). The technology of aviation has become so well-developed, that the reliability of the equipment being used reached a level where design defects or material failures were no longer the major causes of accidents. Much of this development was the result “of the lessons learned from investigating accidents” (Copeland, 1937, p. 2). This trend had been taking place for 30 years, and had been fairly stable for eight years (Taylor, 1990). The human factor was now accounting for approximately 60 to 80 percent of all aviation accidents (Reingold, 1994, p. 25). With the advent of computerization, automatic displays, and high-tech Flight Management Systems, human factor errors, some associated with built-in design flaws, were adding to the number of pilot error problems (Hynes, 1999). However, as a result of a recent crash of an American Airlines’ Air Bus aircraft over New York City, the issues of “design” defects vs. “pilot error” have become a major topic of discussion within the aviation and legal communities. The “legal” posturing of the official NTSB parties to this investigation, American Airlines, Air Bus Industries, and the American Airlines’ pilots union, were thought to be counterproductive to the accident investigation process by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners. 4 Unfortunately, unless a major, high public profile, or politically sensitive aviation accident was being investigated, the investigation process can become a routine “paperwork” activity (Waldock, 1992, p. 164). This expectation of routineness, on the part of many government investigators, resulted in work activities that detracted from the past high quality of NTSB reports (Wolk, 1993). In the US, unless the accident was politically sensitive, or had a high public interest, the average investigation budget for non air carrier accidents was less than $3,000 (NTSB, 1994; Hynes, 1995). This is in stark comparison to major air carrier accident investigations which can cost the NTSB upwards of $25 million dollars each (Asker, 1996, p. 19). As pointed out in the Rand Report (and by Hynes, 1995), some general aviation accident investigations are “carried out by correspondence or telephone” (page 17). However, when John Denver, the well-known song writer and singer, was killed while flying a home-built aircraft, an expensive in-depth NTSB investigation was conducted (Transportation Safety Institute [TSI], 1993). While the results of the investigation had public relations value for the NTSB, the technical findings had little if any value to the majority of the aviation industry who had no interest in home-built aircraft. As pointed out by the Rand study, when famous individuals such as John F. Kennedy, Jr. have an accident while flying, it results in a great deal of public and media attention. In these cases, the NTSB was willing to spend tens of thousands of dollars on a general aviation accident, almost as much as on “the loss of a large commercial airliner” (page 29). The high profile and expensive investigation of the Kennedy crash did not go unnoticed by the aviation press (McKenna, 1999, p. 39). With over 15.0 billion dollars in the US Aviation Trust Fund, all collected from the aviation industry (Jennings, 1993, p. 65) a small portion of these funds would be well spent if they were given to the NTSB for investigating general aviation accidents in more depth (Capt. M. J. Hynes, 1999). For most general aviation accidents, the questions could be raised, (Hynes, 1995); “Are aviation accident investigators becoming conditioned by these statistics and trends?” and “Were government and private computer data bases on accident causation factors becoming distorted because of the input of incorrect or missing information?” The Impact of the Legal System A social concept, common in the US and rooted in old English law, was the undertaking of “tort litigation.” This was the legal remedy available to someone who had suffered a loss because of the acts (or failure to act) by another party (Black, 1991). When an aircraft accident happened, a "loss" to someone, called a plaintiff within the legal system, usually occurs. Personal injury, death and/or loss or damage to property are characteristics of all aviation accidents. Under the legal concept of res ipsa loquitur, (the thing speaks for itself) and other legal theories, claims for damages can be made when accidents take place. To obtain justice within all legal systems, the plaintiff must be able to prove their claim against the alleged negligent party responsible for the loss, who is called a defendant. This proof of loss and negligence must be accomplished before the law will 5 allow a plaintiff to receive compensation from the "wrongdoer" defendant (Madole, 1987). "Proving the claim" invariably requires the plaintiff to have access to correct factual evidence concerning the accident. Under the US government controlled system of aviation accident investigation, only the NTSB, and the parties that the NTSB has designated to join in the investigation, who are never plaintiffs, (unless litigating against each other), were allowed access to accident sites, component inspections and testing, and critical documentation related to the accident (49 CFR, Part 800). Theoretically, all of the factual evidence collected by the NTSB during the investigation process would later be made available to the public. This usually now occurs about 14 months after the accident when the NTSB releases it's Form 6120.4, Factual Report of Aviation Accident/ Incident. In the past, these reports were delayed for up to 30 months or longer for no apparent reason. To add to the problem, in many cases, the NTSB reports have key information deleted from the report and it is not uncommon to find factual errors in many accident reports, especially those that deal with non-air carrier operations (Wolk, Hynes). Questions had been raised by Hynes, Waldock, Wolk, the Rand Report, and others about the NTSB’s policies re. their designation of parties to their investigations. This same question was recently raised publicly by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners. As stated in the Rand Report, as soon as an aviation accident occurs, The effects of litigation begin to be felt at the moment of impact. The specter of dozens, if not hundreds, of lawsuits arises as soon as the magnitude of the tragedy is known. The parties likely to be named to assist in the NTSB investigation--such as the air carrier, aircraft or component manufacturers, or the FAA--are also the most likely to be named defendants in the civil litigation that inevitably follows a major accident” (p. 29). “NTSB investigations of major commercial aviation accidents have become nothing but preparation for anticipated litigation” (p. 30). Confirming the findings of the Rand Report, Chairman Engleman Conners has recently stated that this “litigation preparation activity” by NTSB designated parties was detracting from the overall quality of the investigation process. In many cases, “common knowledge existed that company-sponsored investigators reported directly to their general counsel’s office” (Miller, 2000, p. 29). The timeliness of NTSB reports has also been challenged by Hynes, Wolk, Rand, and others. In 1995, Hynes noted that in some cases, NTSB reports were intentionally delayed until the time period for initiating legal action had passed. (Some legal forums require a claim to be filed within one or two years of the accident event or the claim is disallowed.) In almost every case, the delay in releasing the report is for non-technical reasons (Hynes, 1995; Miller, 2000). “It has been a rule of thumb to experienced investigators that at least 90 percent of the ultimate level of facts learned is available in the first 2 weeks after the crash” (Miller, 2000, p. 30). These writers had shown that the biases of the investigators who conducted the investigation are clearly pro defendant and the influence of the parties whom the NTSB utilized during its factual investigation process (usually defendants), created quality 6 problems and conflicts in the investigation process and the preparation of NTSB accident reports. If by oversight or on purpose, the data collected or used by the NTSB contained errors and/or omissions, when the public was given access to this data, the report could not serve the needs of the interested parties who were usually plaintiffs (Shipman 1992, p. 28; Wolk, Hynes, Rand). To add to this problem, in the early 1990s, additional legal steps were taken by defendants to restrict public access by plaintiffs to government acquired factual data on aviation accidents. Such a restriction resulted from the Iowa District Court ruling during the Air Crash at Sioux City litigation (Re., 1991). The passage by Congress of other similar restrictive legislation in 1992 expanded this limitation concept into the area of military accident investigations (Public Law 102-396). These conflicts of interest, which were reported by Hynes to the NTSB in 1995, were also emphasized in the findings of the 1999 Rand Report. The policies and procedures which impacted aviation accident investigations, seemed to reflect the teachings of aviation accident investigation schools and appeared to follow a very narrow tradition. This tradition was based on seeking only limited technical factual information so that others could later determine probable cause, the final objective of all publicly released, government aviation accident reports (Rand, p. 13). However, by the early 1990s, a major use of these reports by the public was to fulfill the legal requirement of plaintiffs to prove fault and negligence, so that a trier of fact (Judge or jury) could later place blame against one or more of the defendant parties when seeking relief under the US legal system of torts (Miller, Hynes, Rand). While a new concept in the US, the use of official government aviation accident reports to pursue criminal actions in connection with aviation accidents is a common practice in many countries (Flight International, April 11, 2000, p. 9; Aviation Week & Space Technology, August 14, 2000, p. 41). Military investigations are following similar paths, with new emphasis on criminal punishment of military personnel who are involved in aviation accidents (USAF Capt. D. Hynes, 2000; US Marine aviation crash investigation in Italy, 1999). Most instructors of aviation accident investigation schools in the US were former military, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) or NTSB employees who taught the policies and philosophies they had learned and worked under prior to entering an academic institution to teach this subject (TSI). For over 40 years, since the formation of the first formal US aviation accident investigation school in California in the early 1950s, there has been little or no change in the philosophies being taught at these schools (Hynes, 1995). As pointed out in Legal Breakdown (Elias, Randolph, Repa, & Warner, 1990), with the increasing trend of tort litigation in America (which is spreading to other countries) the need for rapid access to correct and complete factual data is critical. The practice of bringing criminal charges as a result of aviation accidents, while common in many countries, is only now becoming an issue in the US as reflected in testimony before the US Congress in July, 2000 (McCarthy). The teaching of the art and science of aviation accident investigation, especially as it addressed, or failed to address, conflicts between the technical and social needs of this activity, is important. 7 As discussed by Transportation Secretary Pena in an aviation trade journal (Lavitt, 1995, p. 26), there had been a continuing public interest in maintaining a high level of safety within the air transportation system. The aviation accident investigation process is still a key factor in achieving that goal. Therefore, the quality and usefulness of aviation accident reports are important to the public, especially if any legal action will result from the accident event. Based on the trends in both civil and criminal litigation, and the government's policy of limiting access to aviation accident sites, component inspection and testing, factual evidence, and important documentation, the conflict between technical and social needs of the investigation process is becoming critical as well as obvious to the public. This issue was stressed by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners in her recent presentation to the aviation community. These actions by government agencies such as the NTSB seriously impede an impartial analysis of the accident (Wolk, Hynes, Rand). As pointed out by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners, the public should now be demanding a more open and impartial system of accident investigation as previously suggested by Wolk, Hynes, Rand, and Hawkins. Statement of the Problem Do conflicts exist between the technical and social aspects of the aviation accident investigation process? Purpose of the Study The purpose of this research was to identify, document, and analyze any conflicts that existed between the technical and social aspects of the aviation accident investigation process. It was intended that the results of the research would then be brought to the attention of the institutions that taught aviation accident investigation courses, to government agencies that conducted and controlled aviation accident investigations, to the aviation accident investigation community, and to the general public, especially attorneys who dealt with the work product of the aviation accident investigation process. Overview of the Study This study traced the development of aviation and the aviation accident investigation process in the US from the early 1900s to the mid 1990s. The goals of an aviation accident investigation, both technical and social, were examined. This was accomplished by researching how the public’s (government) interest in aircraft accident investigations was formalized; how aircraft investigation schools were formed; how investigators were trained; how investigations were conducted; the quality (accuracy) of the investigation findings; the timeliness of the report of the findings; and how investigation findings could be restricted in their use. 8 Concern with the latter three issues--the quality (accuracy) of aviation accident investigation findings, the timeliness of the report of the findings, and how investigation findings could be restricted in their use--were the motivation for this research. This research was conducted in response to the public’s perception of the lack of quality of the NTSB’s investigations which had become an open issue in the 1990s (Hynes, 1995; Rand). The public was demanding a safer air transportation system and wanted to receive compensation, through the legal system if necessary, for injuries and losses whenever the aviation system failed to maintain an acceptable level of safety (Wolk, Miller, 2000). As stated by Hawkins, “In the 1990s, we seem to be coming fairly close to achieving the maximum number of accidents or fatalities, each month or each year, that the public will tolerate without inducing political, and often emotional and unproductive action” (P. 27). With the knowledge gained as a result of this research, the aviation community, both civilian and government, could become more aware of the technical and social aspects of the aviation accident investigation process. Openly discussing these conflicts, such as the recent remarks of NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners, would encourage debate on the need for changes to the existing accident investigation system. In this manner, legal and philosophical improvements could be made to enhance the value of aviation accident investigation techniques and reports. Improvements to the existing system would better meet the needs of society. By doing so, the value of the findings of these investigations to the general public and air travelers might be increased. Limitations of the Study There were several limitations to this study. First of all, the data and the problem were related only to activities in the US. While the world recognized that the US legal system was unique in its pursuit of social or economic justice associated with aviation accidents, social-consumer access to some type of a litigation process is being developed in other countries. While similar technical-social conflicts, within the aviation accident investigation process, also existed in other countries, very often they are associated with only criminal investigations. The potential for criminal investigations in the US is now becoming a concern of many (Campbell, Lewis, G., Quinn, Warren, 2000). As stated previously, non-US activities are not addressed in this study. The second limitation of the study was that most of the reviewed literature had been written by people within the aviation accident system which was being called to question by Hynes’ research. This may have resulted in an imbalance of the discussion of the conflicts between the technical and social needs of the users of aviation accident reports. This unbalance would strongly favor the existing system. The third limitation was the significant influence of national governments, both civil and military, on aviation policy and training since the early days of aviation development. Especially during and after World War II, these agencies selected and trained the aviation experts which later established and then enforced aviation policies. Now, new generations of aviation administrators, technicians, pilots, and accident investigators mirror the philosophies and work habits of these government or military trained experts of years past. 9 A fourth limitation of the study was that around the world and in the US, few organizations offered formal training in aircraft accident investigation. However, because the number of such institutions was so small, a 100% sampling of the US training programs and interviews of their staff allowed this limitation to be capitalized upon. Limitation number five, was the small number of instructors who were qualified and available to teach at these schools (Embry Riddle Aeronautical University [ERAU], 1992; TSI). These instructors, by training, age, and experience, shared common views on many aspects of the aviation accident investigation process. It was very natural for them to continue teaching what was historically always done during previous investigations. By human nature, they might be expected to resist any suggestion that social needs, as well as technical needs, should be considered during the aviation accident investigation process. A final and important sixth limitation of this study was a strong "anti-litigation" bias that existed in much general public interest (Elias et al, Hynes, Wolk, Rand) and technical literature in the field of aviation (Lewis, A., 1993, p. 65). Non-airline aircraft production in the US was less than 500 units in 1994 (FAA Aviation News, 1994, p. 24). In the mid 1960s, annual production rates were in excess of 17,800 aircraft (Bulkeley, 1993, p. 1). This decline in production was blamed on product liability litigation which often resulted in monetary judgments against aircraft manufacturers and other members of the aviation community (Tripp, 1993, p. 116). The General Aviation Revitalization Act of 1993 was passed by Congress at the insistence of the aviation community. This legislation was specifically adopted to prevent litigation against a small number of aircraft manufacturers (about 25) when accidents happened to aircraft over 18 years old. There has been much debate as to the “public value” of this litigation vs. the gains received by a rather small special interest group (The Journal of Air Law and Commerce, Vol. 66, pg.808). The content of much of the aviation literature seemed to reflect this bias. Because of this, a large segment of the aviation community, including aviation accident investigators, and government agencies had no interest in considering the merits of making any changes to the accident investigation process that might prove helpful to potential plaintiffs or the litigation process (Miller, 2000). For these reasons, it is possible that some of the recommendations of this research, and the Rand Report, may not be welcomed by the aviation community, especially government agencies and investigators associated with the accident investigation process. For this reason, the recent public comments by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners could be considered a major shift in the paradigm of thinking about the aviation accident investigation process. If history repeats itself, perhaps the needed changes to the aviation accident investigation process would come in response to the needs of the public, and not from either the aviation community or the legal profession. FINDINGS This research was undertaken to identify, document and analyze the conflicts that existed between the technical fact finding phase of investigations which are used 10 to lead to the determination of probable cause, and the social (finding fault and perhaps blame) aspects of the aviation accident investigation process which are associated with civil or criminal legal actions undertaken long after the official investigation has been closed. The research was designed to answer questions about the public’s perception of the quality, validity, content, timeliness, and usefulness of the NTSB’s aviation accident investigation efforts. The existence of conflicts and the need for change was confirmed by the research. The following questions were also discussed: How did these conflicts develop? Were these conflicts affecting the quality of the accident investigation process? Can changes to the investigation process resolve or reduce the conflicts and improve the system? What changes might be considered? Who was to make the changes? Also documented were other aspects of the accident investigation system which contributed to the conflicts or were deficiencies in themselves. How these conflicts and deficiencies came about, and how they might be resolved were then addressed. Young had stated, "the assignment of (accident) causes as shown (in reports) are to a substantial extent premised upon opinion and conjecture" (Copeland, p. ii). This approach to aviation safety was no longer practicable, prudent, acceptable or necessary. Copeland's message to Congress that "a thorough and searching inquiry should be made into the causes of the wreck...for the prevention of accidents" (p. 1), was even more valid at the time of this study. Despite ex-NTSB Chairman Vogt's statement, "the accident scene belongs to us" (1993, p. 14), others had valid and legal rights to the factual information gained through NTSB investigations. As shown by this research, the current system of aviation accident investigation did not meet society's “social” need for factual data on accidents. Pena’s message, that the US airline industry must abandon its mindset that “every once in a while we have an accident” (January 11, 1995, p.16), acknowledged that the public is demanding a higher level of safety. “(The January 1995) Washington meeting made it clear that air travel within the US has become so accepted, sophisticated, and convenient, that passengers expect it--even demand it--to be virtually risk free” (Aviation Week & Space Technology, 1995, p. 70). As Feldman asked in the April 1995 issue of Air Transport World, “was this just loose talk by Pena and Hinson?” (p. 70). As well known aviation writer and attorney Robert Wright stated, one must accept “a law in action concept”. He emphasized that law was not a static collection of cases or regulations, “Law is a fluid social activity that changes with time and society” (1968, p. x). Adopting the recommendations of this research would diminish these conflicts and improve the value of aviation accident investigations. Because of the existing regulatory structure of the investigation process, and the legal limitations on the use of NTSB work products, the adoption of these recommendations will require action by several government agencies. The FAA, NTSB, Department of Justice, the Courts, and congress will have to adjust their philosophies toward the aviation accident investigation process. Such adjustments will only take place in response to public demands for change. 11 It is up to the public, both air travelers and non-air travelers, the aviation industry, the government, and the legal community, to debate the issues identified by this research and to some degree confirmed by the comments of NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners. If these parties share in the conclusion of the research, that is, that conflicts do exist between the technical (probable cause) and the social (finding fault) aspects of aviation accident investigations, change must be forthcoming. As David North wrote, “Let (the) judicial System Run Its Course in Crash Cases” (May, 2000, p. 66). With over 13.0 billion dollars in the Airways Trust Fund (Jennings, 1993, p. 65), there are ample funds available to undertake these recommendations which would respond to the public’s need for the resolution of the Technical and Social Conflicts of Aviation Accident Investigation, that were acknowledged by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners. RECOMMENDATIONS Considering the events that have taken place during the past five years and the confirmation of Hynes’ 1995 findings by the December 1999 Rand Report, as pointed out by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners, now more than ever, there is a need for changes in the system used for the NTSB’s aviation accident investigation process and reporting system. Based upon the research and its findings in 1995, which have been now updated, the following recommendations are presented: 1. All parties that have an interest in aviation safety, and who are affected by the aviation accident investigation process, should join together to support a major expansion of NTSB funding and significant changes to the NTSB’s Mission Statement (Hynes, p. 168; Rand, p. 55). 2. Military, civil government, and private sector accident investigators must realize that society is now placing equal value on the technical and social aspects of the investigation process. Investigations should be undertaken with this public need in mind and should recognize the need to use high quality, ethical investigation techniques (Hynes, p. 169; Rand, p. 49). 3. The aviation community and general public should also support changes in laws and policies that limit the usefulness of present NTSB investigative efforts. Everyone must agree that all accident investigations deserve equal effort, that safety lessons can be learned from all accidents, and that accidents should not be considered as “random events” (Hynes, p. 168; Rand, p. 47). 4. The private, government, and military organizations that teach accident investigation techniques must better consider both the technical and social aspects of the investigation process and incorporate these needs into their curriculums. Teaching material should address the potential for conflicts in the present investigation system and openly discuss this as part of the training of investigators. Schools should also emphasize the need for high quality, ethical investigation techniques (Hynes, p. 169; Rand, p. 55). 5. Government, industry and private sector attorneys should recognize the existence of conflicts between the technical and social aspects of the accident investigation process and that these conflicts cause problems with the quality of NTSB 12 efforts as commented by NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners. As stated in the original research paper (Hynes, p. 169) and confirmed here, the legal community should: a. demand a higher level of ethics during the investigation and reporting process; b. demand reasonable equal access by plaintiffs and defendants to accident sites and factual information during the NTSB (and military) investigation process; c. request input from all parties during the investigation process and require NTSB reports to contain minority opinions as to conflicting factual evidence when such opinions exist; d. allow public access to, and use of, all factual evidence obtained during NTSB investigations. 6. The NTSB should: a. analyze, and then apply more correct “key word” terminology to existing FAA and NTSB accident report computerized data bases. Then combine the two sets of data into a single source of important aviation safety data history. This information should be of higher quality and stored in a single data base with more uniform retrieval capabilities by the public (Hynes, p. 169; Rand, p. 51); b. begin the collection and storage of incident and mishap data through a voluntary reporting system similar in nature to the NASA “Aviation Safety Reporting System” (ASRS) and programs in use in other countries (Hynes, p. 170; Rand, p. 51); c. review the outcome of litigation undertaken as a result of aviation accidents, or in some cases business disputes between aviation related companies (i.e. Robinson Helicopter v. Dana, No. 04 C.D.O.S 11217 and Interstate Forgings v. Textron Lycoming) to determine if new factual evidence was discovered or errors in NTSB Factual Reports exist; d. when new factual evidence is found that has significance to existing NTSB Reports, corrections should be added to the NTSB and FAA aviation accident computerized data base, and if appropriate, the Factual Report Aviation, previously issued by the NTSB should be corrected or at least expanded to include this new data. The findings of litigation efforts should be used as a means of quality control for past NTSB and FAA accident reporting efforts (Hynes, p. 170; Rand, p. 52); 13 e. restrict the FAA’s role in the investigation process as much as possible until the NTSB’s initial safety investigation is complete (Hynes, p. 170); f. restrict as much as possible evidence gathering activities associated with civil or military criminal prosecution efforts during the investigation process until the NTSB’s initial safety investigation is complete; g. when possible, diminish the role of manufacturers, suppliers and other potential defendants during the investigation process by utilizing qualified outside contractors for some of the required component tests and inspections (Hynes, p. 170; Rand, pp. 30, 47, 48); h. issue NTSB reports on a timely basis. Except for major accidents, full or partial Factual Reports should be issued within 90 to 120 days. The Probable Cause Reports should be issued within 60 days of the Factual Report (Hynes, p. 170; Rand, p. 51); i. discontinue reporting "none found" in the NTSB Factual Report Form 6120.4, Part Failure/Malfunction (Box 143) that concerns mechanical failures and other technical issues when no serious effort was made by the NTSB to find this information. The correct answer in such a case would be, "Not determined" and an explanation as to the reason for the lack of component examination or testing should be made part of the report (Hynes, p. 170); j. identify missing or redacted elements of NTSB reports. Reasons why information was missing from publicly available NTSB Reports or data files should be provided (Hynes, p. 170); k. require NTSB and FAA investigators to have more experience in aviation technical subjects (Hynes, p. 170; Rand, p. 54); l. where “pilot error” seems to be one of the major probable causes of the accident, input from a pilot expert with experience in a similar make and model of the accident aircraft should be sought and included in the report. Where possible, some discussion or comments as to the “cause” or possible reasons for the pilot error should be included in the report (Hynes, p. 170; Rand, p. 54); 14 m. increase NTSB “on-site” investigator staffing. (Hynes, p. 170; Rand, p. 53, Connors, p. 51). When possible, all accident investigations that resulted in fatalities should have a minimum of two NTSB persons present at the accident site; n. unless an accident is very minor in nature, all “telephone” and/or correspondence only investigations should be eliminated (Hynes, p. 170); o. the NTSB aviation accident investigation staff should be divided into two sections; one section, based in Washington, DC, would continue to act as the “go team” for major accidents and a second section, assigned to various areas of the US, would be assigned to conduct field investigations of general aviation accidents; p. increase NTSB laboratory facilities and staff (Hynes, p. 171; Rand, pp. 37, 55) to conduct more tests of critical components and/or utilize contractors for inspection and testing of these items. If tests may have an impact on future litigation, test costs could be paid for by the party requesting the test. The NTSB should be a neutral observer and resolver of testing technique conflicts; q. make a stronger effort to protect all evidence during testing, and ensure that there is no evidence spoliation, and/or make sure that items are not misplaced for long periods of time or, in the extreme, never found as is the current situation; r. provide more training of investigators, including attendance at non-NTSB investigation schools; courses in a wide variety of aviation related skills should be provided to all field NTSB investigators. Advanced investigator training must be completed prior to a person being assigned as the NTSB Investigator in Charge (IIC). Continuing education of investigators, (Hynes, p. 171, Rand, pp. 55, 59); s. establish more reasonable work schedules for NTSB staff, especially on site investigators (Hynes; Rand, pp. 23, 53); t. attempt to minimize the adverse psychological effects on NTSB investigators of constant work at the task of accident investigation (Hynes, p. 171; Rand, pp. 23, 53). Provide “post trauma” psychological training and counseling to investigators in address this area of emotional stress (Hynes, p. 171). 15 CONCLUSIONS Hynes’ study and recommendations, which were sent to NTSB Chairman Hall in 1993, 1994, and 1995, were still valid when the Rand Report was issued in December 1999. When this research was up-dated in late 2000, and again in early 2005, Aviation trade journals, newspapers, TV, and other media are all reflecting public concern with the safety of today’s air transportation system. NTSB Chairman Engleman Conners recently publicly expressed similar concerns. Everyone seems to be looking to the FAA and NTSB to recognize and solve the problems being discussed in this paper. As Don Fuqua, former President of the Aerospace Industries Association stated, “…the aviation community has built a superior transportation system. It (the US system) is still the safest on this planet. But even the safest system can be improved.” (1997, Jan, p. 2). While aviation writers such as Kent Jackson may lament the American legal system, (Jury-Rigging Aviation, October 2001, p. 114), the ethics of the present day business community raises serious doubts as to the integrity of the aviation accident investigation process. While Jackson is correct that, “the vast majority of people in the business of aviation love these flying machines, and like working with others who share the same affliction”, he fails to acknowledge the level of corruption in business today. On a daily basis, The Wall Street Journal contains numerous articles about fraud in corporate America. As these matters come before the public, we see not just single individuals committing these crimes, we see groups of people, acting together to gain wealth at the expense of the public welfare. As confirmed by recent litigation between major aviation firms (Robinson v. Dana and Interstate Forging v. Textron-Lycoming), greed is not excluded from the aviation community. With millions of dollars “of profits” at stake, management seems willing to instruct its employees to take steps to protect the corporation’s bottom-line at any cost. When made aware of evidence presented during trials, the prevailing attitude toward litigation at the NTSB and FAA, is expressed by FAA Chief Spokesperson, Greg Martin who recently stated, “Court cases have their own dynamics (based on) who is more persuasive to the jury.” At what level the public will become outraged at this type of reaction by the FAA and NTSB toward sub-standard management ethics within the aviation community is still yet to be determined. If the conditions identified as a result of this research are properly addressed, perhaps it will become easier to see “Kindness and truth shall meet, justice and peace shall kiss. Truth shall spring out of the earth, and justice shall look down from Heaven.” (Psalms 85, 11-12) for matters dealing with the Technical and Social Conflicts of Aviation Accident Investigations. For additional information, contact: Dr. Michael K. Hynes, President and Director of Aviation Research Hynes Aviation Services 1002 Cliff Drive Branson, MO 65616-2611 Phone: 417.335.5759 Email: hynesdrm@aviationonly.com 16 REFERENCES and BIBLIOGRAPHY Air Commerce Act of 1926. Washington, DC. Allen, G. (1990, Fall). The View from Justice-The Independent Safety Board Act Amendments of 1990: Changing the Rules. LPBA Journal. Lawyer Pilots Bar Association, XII (1). Asker, J. (1996, Nov, 25). Sleuthing TWA 800. Aviation Week & Space Technology: NY. Aviation Consumer. (1986, May 1). Product Liability: If we Ruled the World...How to solve the product liability “crisis”? We’re glad you asked. Palm Coast, FL Aviation Week & Space Technology. (1995, Jan 23). Editorials: Zero Accidents, Zero Excuses. NY. Aviation Week & Space Technology. (1995, Feb 20). NTSB Proposes No-Growth Plan. NY. Aviation Week & Space Technology. (2000, Aug 14). Concorde Sparks Debate On Criminalizing Crashes. NY. Bible, Old Testament. Isaiah I, 17. Bible, Old Testament. Psalms, 85, 11-12. Bilstein, R. (1984). Flight in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. Black, H. (1920). Black's law dictionary. (1991 ed.). St. Paul, MN: West. Bulkeley, W. (1993, Oct 19). Small-Plane Makers May Get a Big Lift From Congress. Wall Street Journal. NY. Burnham, F. (1977). Cleared to land: The FAA story. Fallbrook, CA: Aero. Campbell, Daniel. (2000, Jul 27). Testimony before the US Congress, House Transportation Committee, WDC. Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938. Sec. 701 (e). WDC. Civil Aeronautics Administration. (1941, Mar 22). Air Safety Board Recommendations. WDC. Civil Aeronautics Authority. (1953). Aircraft Design Through Service Experience. Copeland, A. (1937, Mar 17). Safety In The Air, Report No. 185. 75th US Congress. WDC. DelGandio, F. (1990, Nov). FAA Aircraft Accident Investigation: Nine areas of responsibility. “Crash Course” Newsletter, 1 (2), 1-2. Oklahoma City: Transportation Safety Institute. DelGandio, F. (1991, Oct). Delegated accidents. “Crash Course” Newsletter. Department of Commerce. (1931). Report to Congress. WDC. Department of Commerce. (1940). Civil Aeronautics Journal. WDC. I (1). Department of Transportation Act. (1966). PL 89-670, 49 USC 1651. WDC. Dorman, M. (1976). Detectives of the Sky: Investigating Air Tragedies. NY: Franklin Watts. Duke, T. (1999, Oct 25). Viewpoint. Aviation Week & Space Technology. NY. Engleman Conners, Ellen. (2003, June 16). Aviation Week & Space Technology. NY. Engleman Conners, Ellen. (2005, January). Aviation Week & Space Technology. NY. Engleman Conners, Ellen. (2005, February 3). The Wall Street Journal. WDC. Elias, Randolph, Repa & Warner. (1990). Legal Breakdown. Berkeley, CA: Nolo. Embry Riddle Aeronautical University. (1992). Aircraft Accident Investigation Course. Prescott, AZ. Erickson, L. (1992). Litigation in Aviation. WDC: American Bar Association. Fagg & Wigmore. (Eds.). (1929). Journal of Air Law and Commerce. Chicago: Northwestern University. Fair, M., & Guandolo, J. (1972). Transportation Regulation. Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown. Federal Aviation Administration. (1967). DOT Act of 1966, PL 89-670, 49 USC 1651. WDC. Federal Aviation Administration. (1994, Oct). FAA Aviation News. WDC. Federal Aviation Agency Act. (1958). PL 85-726, 49 USC 1301. WDC. Feldman, J. (1995, Apr). On Zero Accidents, Safety and Loose Talk. Air Transport World. Flight International. (2000, Apr 11). Crash pilot on manslaughter charge. Surrey, UK. Forlow, Hotchkiss, Kanuth & Niles. (1929). Pilot’s Manual of Air Law. Baltimore: US Aviation Reports. Gardere & Wynne. (1990, Sep). Outsiders May Not Be Welcome. Aviation Law Newsletter. Dallas, TX. 5 (3). General Aviation News & Flyer. (1995, Mar 31). Will NTSB be able to keep up with its new responsibilities?, Lakewood, WA. General Aviation Revitalization Act of 1994. HR. 3087 and S. 1458. Hawkins, F. (2000). Human Factors in Flight. Brookfield, VT: Ashgate. Heller, J. (1993). Maximum Impact. New York: Tom Doherty Associates. HR Report No. 933. (1941, Jul 10). Investigating Air Accidents. 17 Hynes, Lt. D. (1995, Mar 10). Relationship of Government Aviation Agencies in the United States. Unpublished paper. Embry Riddle Aeronautical Institute, Daytona Beach, FL. Hynes, Capt. D. (2000, Jul 20). Interview. Hynes, Capt. M. J. (1994, Feb 1). Pilots Know Your Rights. The View from the Right Seat: IACP IAH FO REP PUBLICATION. Houston: Independent Association of Continental Pilots. 1 (1), 1. Hynes, Capt. M. J. (1999, Jul 25) Interview, Continental Airlines. Hynes, M. K. (1967, Mar). Airline marketing in the 1960's. Unpublished Paper. Polk Community College, School of Marketing, Winter Haven, FL. Hynes, M. K. (1990, May-Jun). Misconceptions About FAA/NTSB Aviation Accident Investigations. Experts At Law. North Hollywood, CA: Legal Publishers. Hynes, M. K. (1991). History and analysis of the system used for the certification of aircraft pilots in the US. Unpublished Thesis. University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK. Hynes, M. K. (1994, Feb). Use and admissibility of aviation accident reports. Impact of Federal Aircraft Accident Investigations Upon Civil Litigation-Myth or Reality. Proceedings of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators, Mid-Atlantic Regional Chapter Meeting. Washington, DC. Hynes, M. K. (1995). Technical and Social Conflicts of Aviation Accident Investigations. Dissertation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK. Hynes, M. K. (1999, Aug). Commuter Passenger Safety in the US Air Travel Market and the Need for Passenger Entrance Door Stair Handrails. Western Oklahoma State College, unpublished paper. Hynes, M. K. (2000, May). The History of Getting On and Off Commuter Airplanes: Passenger Injury Accidents Resulting from Engineering and Regulatory Shortcomings. SAE 2000 Conference & Exposition, Wichita, KS. Paper No. 2000-01-1661. Independent National Transportation Safety Board Act of 1974. PL 93-633, 49 USC 1901. WDC. Interstate Forgings v. Textron-Lycoming, Grimes County, TX. (2005, February 17). AVflash. NY. Belvoir. Jackson, Kent S. (2001, October). Business and Commercial Aviation. NY. Jennings, M. (1993, May). Trust us: we’ll spend $13 billion. Airline Business. Johnson's Record. (1926). (10 Am Dec). American Decision. WDC: Bradley Tyler. Josephy, A. (1962). History of Flight. New York: American Heritage. Lavitt, M. (1995, Jan 10). Pena calls summit on airline safety. Aviation Week & Space Technology. NY. Lederer, J. (1939, Apr 20). Lecture: Safety in the Operation of Air Transportation. Norwich, CT: Norwich University. Lederer, J. (1992, Mar). Is probable cause(s) sacrosanct?. ISASI Forum. Sterling, VA. Lewis, A. (1993, Feb). Management Fighting City Hall. Business & Commercial Aviation. NY. Lewis, G. (2000, Jul 27). Testimony before the US Congress, House Transportation Committee, WDC. Madole, J. (Ed.). (1987). Litigating the Aviation Case: From Pretrial to Closing Argument. WDC: American Bar Association. Martin, Greg. (2005, February 21). AVflash. NY. Belvoir. Mathews, M. (1995, January, 2). Aviation Week & Space Technology. NY. McCabe, J. (1991). The Unreliability and Inadmissibility of Government Aviation Accident Reports. LPBA Journal, XIII (1). McCarthy, Capt. P. (2000, Jul 27). Testimony before the US Congress, House Transportation Committee, WDC. McKenna, J. (1999, Jul 26). Kennedy Crash Probe Begs NTSB Questions. Aviation Week & Space Technology. NY. McNair, A. (1930). The Beginning and Growth of Aero Law. The Journal of Air Law and Commerce. 1 (4). Miller, C. (1992, Spring). Probable Cause: The correct legal test in civil aircraft accident investigations? LPBA Journal. Lawyer Pilots Bar Association. Miller, C. (1993, Sep). Compatibility of Air Safety Investigations and Civil/Criminal Litigation. ISASI Forum. International Society of Air Safety Investigators. Miller, C. (1994, Sep 12). Reader Reaction: Letters. Aviation Week & Space Technology. Miller, C. (2000, Jun-Sep). Assessing the Rand Corporation Study: Safety in the Skies-Personnel and Parties in NTSB Aviation Accident Investigations. ISASI FORUM. Sterling, VA. National Transportation Safety Board. (1992). 1994 Budget Request. WDC. National Transportation Safety Board. (1992). Factual Report Aviation Accident/Incident, Form 6120.4. WDC 18 Ogburn, W. (1945). Social Aspects of Aviation. NY: Houghton Misslin. Pena, F. (1995, Jan 11). Secretary issues call for safer air travel. Daily Oklahoman. Public Law PL102-396. (1992). WDC. Quinn, Kenneth. (2000, July 27). Testimony before the US Congress, House Transportation Committee, WDC. RAND, (1999). Safety in the Skies, Personnel and Parties in NTSB Aviation Accident Investigations. Santa Monica, CA: Institute for Civil Justice. Re. Air Crash Sioux City. 708F. Sup. 1207 ND IL 1991. Re. Guille v. Swan, (1822) 10 Am Dec. Reingold, L. (1994, Jul). Search for Probable Causes. Air Transport World. Robinson v. Dana (2005, January 3). THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL. NJ. Schleede, R. Interview, 02/17/94, NTSB Aviation Accident Investigator. WDC. Shipman, R. (1992, Dec). NTSB: Friend or foe. Air Line Pilot. Squier, Lt. A. (1908, Sep 18). Proceedings of the Aeronautical Board of the Signal Corps. War Department Report, National Archives: WDC. Steenblik, J. (1992, Jun). Probable Cause: Help, or red herring? Air Line Pilot. Steenblik, J. (1994, Jul/Aug). Fine Tuning the Safety Board. Air Line Pilot. Taylor, R. (1990, Jul 23). Twin-Engine Transports: A Look at the Future. WDC: The Boeing Company. Taylor, J. & Munson, K. (1972). History of Aviation. New York: Crown. Transportation Safety Institute. (1993). Aircraft Accident Investigation Course. Oklahoma City. Tripp, E. (1993, Sep). Beyond Product Liability. Business & Commercial Aviation. Truman, H. President. (1947, Jun 15). Letter to the Civil Aeronautics Board. US Air Force. (1993). Flight Safety Handbook. WDC. US Navy. (1957). Handbook for Aircraft Accident Investigators. Pensacola, FL. US Navy. (1957). Navy Aviation Accident Investigation Course Guide. Monterey CA: Naval Post Graduate School. US Navy. (1975). United States Navy Aviation Accident Investigation Course Guide. Pensacola, FL. Vivan, C. (1921). A History of Aeronautics. London: W. Collins Sons. Vogt, C. (1993, Aug). The Probable Cause. Aerospace. Royal Aeronautical Society. Waldock, W. (1992). Aircraft Accident Investigation and the Training of Air Safety Investigators: Their Effective Use in Aviation Litigation. Proceedings of Lawyer-Pilots Bar Association Annual Seminar, Tempe, AZ. Waldock, W. (1992). Training of Air Safety Investigators, Now and For the Future. ISASI Forum. Walsh, J. (1975). One Day at Kitty Hawk. New York: Thomas Crowell. Ward, B. (Ed.). (1953). Flight-A Pictorial History of Aviation. Los Angeles: Year. Warren, R. (2000, Jul 27). Testimony before the US Congress, House Transportation Committee, WDC. Wingfield & Sparkes. (1928). Laws in Relation to Aircraft. London: Longmans, Green. Wolk, A. (1984, Oct). Point of Law: Products Liability-Aviation’s Nemesis or Conscience (A Personal Opinion). Business and Commercial Aviation. McGraw-Hill. Wolk, A. (1993, Sep 1). Calls and Letters. Aviation Convention News. Midland Park, NJ. Woodhouse, H. (1920). Textbook of Aerial Laws. New York: Frederick Stokey. Wright, R. (1968). The Law of Airspace. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill. Young, C. (1931). Report to Congress. WDC. 49 CFR Part 800. (1994). Organization and Functions of the Board and Delegations of Authority. National Transportation Safety Board. WDC. 19