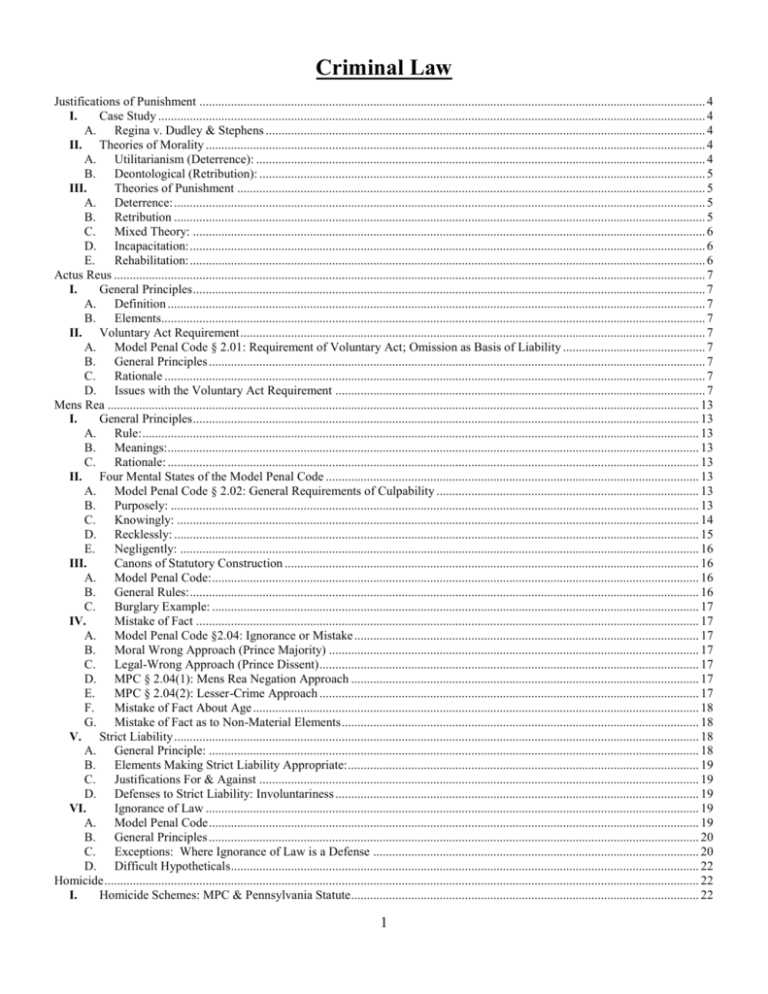

Justifications for Punishment

advertisement