Memo - LLS

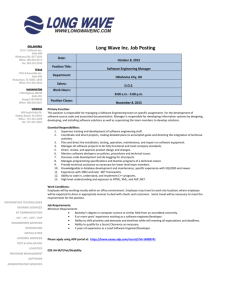

advertisement

MEMORANDUM TO: FROM: RE: DATE: Charles Houston Stephen Terrell Ada Sipuel Complaint October 12, 1999 Attached please find a copy of the complaint for the Ada Sipuel litigation. Below I outline several strategic decisions made when drafting the complaint. I. FORUM I chose to file the Sipuel litigation in state court. I recognize that state court judges may not be as friendly to our claim as “impartial” federal court judges, and that state court judges face reelection and may be influenced by political and social forces surrounding this controversial litigation. At the same time, we have a very strong legal case. See State of Missouri et. rel Gaines v. Canada 305 U.S. 337 (1938); see also Pearson v. Murray 169 Md. 478 (1936.) Despite any political or social pressures, the judges of the State of Oklahoma have taken an oath to uphold the laws of the United States and the State of Oklahoma. There is little doubt that Ms. Sipuel’s admission to the University of Oklahoma School of Law, no matter how unpopular, is mandated by current law. By filing in state court we avoid all abstention issues. Several of our claims are based on the Oklahoma Constitution and may be subject to abstention if brought originally in federal court. See Railroad Commn. of Texas v. Pullman Co. 312 U.S. 496 (1941). Also, by filing in state court we avoid the Eleventh Amendment in that we may name the State of Oklahoma as a defendant. We are directly attacking Plessy, and by filing in state court we may avoid sanctions for bringing such a bold claim that could be levied in federal court under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rule 11. A favorable decision in an Oklahoma Superior Court will not be binding on other 1 jurisdictions and, therefore, will not immediately achieve our goal of overturning Plessy. None the less, I am confident the State of Oklahoma will appeal any decision unfavorable to them all the way to the Supreme Court, and I know we will do likewise. II. PARTIES Ms. Sipuel is the only named plaintiff. Any relief she may get will likely have systemic effects, and a declaration that the laws of Oklahoma are unconstitutional as applied to her likely implies they are unconstitutional as applied to all Negroes. Although admissions cases are necessarily fact-specific, I believe an opinion can be obtained addressing questions of law, allowing future plaintiffs to use offensive issue preclusion. Therefore, we can avoid the trouble and expense of certifying a class by naming only Ms. Sipuel. As defendants I named the State of Oklahoma, all officers involved in the policy making and execution of the segregated system of higher education within the state, and those officers responsible for enforcing the racially discriminatory statutes affecting Ms. Sipuel’s situation. All defendants are sued in their official capacity for prospective injunctive relief and the real parties are named in their individual capacity for damages. I understand that the State of Oklahoma and the Oklahoma State Reagents for Higher Education cannot be sued, even in state court, for damages under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. See Will v. Michigan Dept. of State Police 491 U.S. 58 (1989). I also understand there are substantial immunity issues, but those will be addressed at trial. III. CLAIMS As stated previously, it is clearly established that Ms. Sipuel should be admitted to the law school and it is unconstitutional for the state to deny her admission because of her race without providing substantially equal facilities for Negroes. See Gaines, supra. By providing a 2 Fourteenth Amendment equal protection cause of action along with various Oklahoma Constitution causes of action two objectives are achieved: first, Ms. Sipuel is more likely to get the relief sought, that is, admission to the law school; and second, res judicata (claim preclusion) is avoided. Ideally we seek to overturn Plessy, and some of the state claims provide the court with the option of providing Ms. Sipuel with her relief without upsetting Plessy. This is an unfortunate reality, but ethically we must bring these claims. Also, there are malpractice concerns if we do not bring all of these claims. Additionally, it is not detrimental to our cause if a court holds that the Oklahoma Constitution secures more civil rights than the Federal Constitution. I also included a privileges or immunities claim under the Fourteenth Amendment. This cause of action has been dormant since The Slaughter-House Cases 83 U.S. 36 (1872). Basing constitutionally protected civil-rights on the equal protection clause is like hanging an elephant by a thread. At the same time we attack the incorrectness of Plessy, I believe we should also challenge the wrongly decided The Slaughter-House Cases. By combining a fundamental-rights analysis of due process with a natural justice approach implicit in the privileges or immunities clause (as originally perceived by the framers) this claim will provide novel food for thought to the court. Although I do not expect this claim to be ultimately successful, I believe it is important we make a statement in the interest of law reform. IV. RELIEF The specific relief sought is Ms. Sipuel’s admission to the University of Oklahoma Law School. Pendant to this is a necessity that Ok. St. T. XX § XXX be enjoined from being enforced in Ms. Sipuel’s situation. I have tried to phrase the declaratory and injunctive relief in a manner which overrules Plessy. In doing this I ask the court to declare that 3 segregated higher education is inherently unequal and per se unconstitutional. Damages under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 may be nominal because of immunity issues mentioned above. None the less, even nominal damages will allow us to try to recoup our attorneys’ fees under 42 U.S.C. § 1988, which could be very beneficial to our cause. 4