The History of Cambodia 1953

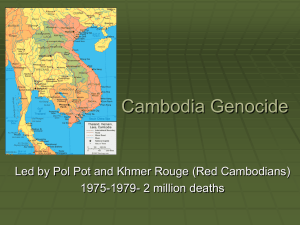

advertisement

The History of Cambodia 1953-1968 Cambodia won its independence from France on November 9, 1953, officially ending eight decades of colonial control. Twenty-two-year-old King Norodom Sihanouk returned from exile to lead the new country. After stepping down from the throne to become prime minister in 1955, Sihanouk insisted that Cambodia remain neutral and avoid foreign influences. As the Cold War heated up in Southeast Asia, the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations feared that Cambodia might fall to communism and wanted to use it as a buffer against North Vietnam. Speaking about the strategic importance of Southeast Asia in 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower warned, “You have a row of dominoes set up. You knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly.” Sihanouk accepted temporary assistance from the United States, but he also resented its interference in Cambodian affairs. As the American military presence in Southeast Asia escalated, however, Sihanouk decided to distance himself completely from the United States. In March 1965, U.S. Marines landed in South Vietnam, beginning a new phase of the war. Sihanouk had rejected American military aid two years earlier, and now he broke off all diplomatic relations with the United States. His relationship with communist North Vietnam became increasingly cozy. By 1967, the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong were operating along Cambodia’s border with South Vietnam, with Sihanouk’s approval. The United States and South Vietnam responded with cross-border operations, which Sihanouk publicly protested. As Cambodia was drawn into the bloody conflict next door, Sihanouk’s dream of Cambodian neutrality quickly faded. For now, Cambodia would not be the next “domino” to topple over. But it had become a new battlefield – some called it a sideshow – in the American war in Vietnam. During this period, many Cambodians revered Sihanouk as a god-king and respected him for keeping the country relatively peaceful. But there was growing opposition to his government’s corruption and intolerance of dissent. In 1960, a small group of leftist intellectuals, including Saloth Sar (later known as Pol Pot) and Nuon Chea, formed the Communist Party of Kampuchea. The small, highly secretive organization operated in the capital, Phnom Penh, until 1963, when its leaders fled to the countryside and launched an armed insurgency. At the time, the communist guerillas posed little threat to Sihanouk and became known simply by the dismissive moniker he gave them: the Red Khmer, or Khmer Rouge. 1969-1974 On March 18, 1969, American B-52s began carpet-bombing eastern Cambodia. “Operation Breakfast” was the first course in a four-year bombing campaign that drew Cambodia headlong into the Vietnam War. The Nixon Administration kept the bombings secret from Congress for several months, insisting they were directed against legitimate Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge targets. However, the raids exacted an enormous cost from the Cambodian people: the US dropped 540,000 tons of bombs , killing anywhere from 150,000 to 500,000 civilians. Shortly after the bombing began, Sihanouk restored diplomatic relations with the US, expressing concern over the spread of communism in Southeast Asia. But his change of heart came too late. In March 1970, while Sihanouk was traveling abroad, he was deposed by a pro-American general, Lon Nol. The Nixon Administration, which viewed Sihanouk as an untrustworthy partner in the fight against communism , increased military support to the new regime. In April 1970, without Lon Nol’s knowledge, American and South Vietnamese forces crossed into Cambodia. There was already widespread domestic opposition to the war in Vietnam; news of the “secret invasion” of Cambodia sparked massive protests across the US, culminating in the deaths of six students shot by National Guardsmen at Kent State University and Jackson State University. Nixon withdrew American troops from Cambodia shortly afterwards. But the US bombing continued until August 1973. Meanwhile, with assistance from North Vietnam and China, the guerrillas of the Khmer Rouge had grown into a formidable force. By 1974, they were beating the government on the battlefield and preparing for a final assault on Phnom Penh. And they had gained an unlikely new ally: Norodom Sihanouk, living in exile, who now hailed them as patriots fighting against an American puppet government. Sihanouk’s support boosted the Khmer Rouge’s popularity among rural Cambodians. But some observers have argued that the devastating American bombing also helped fuel the Khmer Rouge’s growth. Former New York Times correspondent Sydney Schanberg said the Khmer Rouge “… would point… at the bombs falling from B-52s as something they had to oppose if they were going to have freedom. And it became a recruiting tool until they grew to a fierce, indefatigable guerrilla army.” Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger has dismissed the idea that the US bears any responsibility for the rise of the Khmer Rouge. As he argued in his memoir, “It was Hanoi-animated by an insatiable drive to dominate Indochina- that organized the Khmer Rouge long before any American bombs fell on Cambodian soil.” 1975-1979 On April 17, 1975, less than two weeks before the fall of Saigon, the Khmer Rouge seized Phnom Penh and immediately began to drive the city’s 2 million residents into the countryside. This was the first stage in its brutal attempt to transform Cambodia into a primitive communal utopia. In reality, the Khmer Rouge turned the country into an enormous forced labor camp. Money, property, books and religion were outlawed. Cambodia’s economy, already severely damaged by years of bombing and civil war, ground to a halt. All decisions in the newly renamed Democratic Kampuchea came from a shadowy and unquestionable leadership known simply as angkar,or “the organization.” In less than four years, between 1.7 million and 2.5 million people died, out of a population of 8 million. Many succumbed to starvation or exhaustion. Tens of thousands were tortured and executed in places like Phnom Penh’s infamous Tuol Sleng prison. The Khmer Rouge completely closed Cambodia to the outside world. But reports of atrocities trickled out of the country, sparking a debate in the United States and the West. News of mass killings and starvation seemed to vindicate those who had predicted a bloodbath once the Khmer Rouge came to power. However, some antiwar activists questioned the accuracy of these reports, claiming that they were exaggerations meant to discredit the new Communist regime. In the face of mounting evidence of Khmer Rouge atrocities, the U.S. government stayed quiet. After the debacle of the Vietnam War, few American politicians were willing to get reinvolved in Southeast Asia, and the government was not eager to examine its complex role in Cambodia’s collapse. Not until April 1978 did President Jimmy Carter declare the Khmer Rouge “the worst violator of human rights in the world.” By then, the Khmer Rouge had less than a year left in power. Ironically, its downfall was brought on by a conflict with its former ally, Vietnam. A border dispute between Democratic Kampuchea and communist Vietnam flared into full-scale war, and in January 1979, Vietnamese forces rolled into Phnom Penh. 1992-2002 U.N. peacekeepers arrived in Phnom Penh in March 1992 to supervise the revival of Cambodia’s constitutional monarchy. The following year, elections were held and a new constitution was ratified. Once again, Norodom Sihanouk assumed the throne, while Hun Sen shared the office of prime minister with Sihanouk’s son, Prince Norodom Ranariddh. However, Cambodia’s troubles were far from over. Its economy was in ruins, tens of thousands of people remained displaced and the countryside was littered with as many as 8 million land mines. And Sen, who would oust Ranariddh in a bloody 1997 coup, was criticized for his autocratic style and human rights abuses. Having distanced itself from the Khmer Rouge, America’s relations with Cambodia improved significantly in the 1990s. Congress granted Cambodia most-favorednation trading status and restored aid to the government. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed the Cambodian Genocide Justice Act, which advocated bringing the perpetrators of the Khmer Rouge’s crimes to trial and provided $400,000 to research and collect information about the genocide. Pol Pot and other Khmer Rouge leaders continued to live freely in Cambodia and Thailand, though they became increasingly isolated. In 1996, almost half of the remaining Khmer Rouge forces surrendered to the government and received amnesty. As pressure to arrest Pol Pot mounted, the Khmer Rouge declared that it had sentenced him to life imprisonment for his crimes. In April 1998, the enigmatic mastermind of the killing fields died of heart failure, disappointing those who wished to see him brought before an internationally recognized tribunal. To date, two Khmer Rouge leaders, including the former head of Tuol Sleng prison, have been arrested and charged with genocide. However, they cannot be tried until Cambodia and the United Nations settle an ongoing dispute over how to set up genocide tribunals. Some observers have criticized Prime Minister Hun Sen’s hesitation to aggressively pursue the Khmer Rouge leadership. In 1999, he accepted Nuon Chea’s surrender and apology, and he has suggested that Cambodia “dig a hole and bury the past.” Recently, Sen – a former Khmer Rouge soldier himself – has said he supports tribunals but wants to minimize outside interference in establishing them. Cambodia is still trying to recover from one of the 20th century’s most horrific crimes against humanity. How it will recover from this trauma remains subject to debate, both inside Cambodia and abroad. Some say Cambodians must move on and focus on rebuilding their country. Others say Cambodia will suffer from a “culture of impunity” until its former leaders are held accountable for their actions. And others insist that any examination of the Khmer Rouge years must also address Cambodia’s troubled recent history and the United States’ controversial role in it. Frontline World. Cambodia: Pol Pot’s Shadow. PBS, October 2002.

![Cambodian New Year - Rotha Chao [[.efolio.]]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005298862_1-07ad9f61287c09b0b20401422ff2087a-300x300.png)