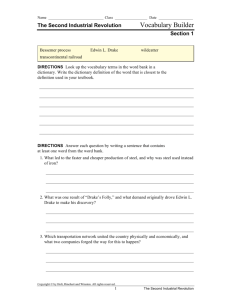

Magnet 1663-B

advertisement