Multinational Financial Management

Money serves three functions:

FOREIGN EXCHANGE RATES

1) A medium of exchange -- as opposed to a barter system, money is used as a transactional medium, so that we do not have to trade a car wash, a dinner, yard care, etc., for the teaching services of a professor.

2) unit of account -- the value of goods and services can be measured by money, as opposed to expressing the value of a car as "six thousand bushels of wheat", etc.

3) a store of value -- we can accumulate money over time to allow for more consumption in the future in exchange for consumption today. Not all currencies (monies) are equally good as a store of value. Compare, for example, the U.S. dollar versus the Russian ruble.

Each country has its own unit of money. While money can be used as a medium of exchange within a country, foreign exchange markets have arisen in order to allow the exchange of goods and services between countries by making currencies convertible into one another. The foreign exchange rate simply expresses the value of one currency in terms of another. In other words, the foreign exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of another. As with any commodity, price is a function of supply and demand. The higher the demand and the lower the supply, the greater the price and vice versa.

The spot rate of a currency is the rate at which one currency can be converted into another immediately . The spot rate can be expressed as a direct rate

Direct Rate

Domestic

Foreign

Currency

Currency U nit

or on an indirect basis

Indirect Rate

Foreign

Domestic

Currency

Currency U nit

Generally, the U.S. dollar is quoted on an indirect basis. For example, there are 10.35

Mexican pesos per 1 U.S. dollar (Mex$10.35/USD), or 125 Japanese yen per 1 U.S. dollar

(¥125/USD). The exceptions tend to be relative to British, and formerly British colonies', currencies such as 1.70 U.S. dollar per pound sterling (1.70/USD), USD 0.65 per Canadian dollar

(USD 0.65/C$), and USD 0.80 per Australian dollar (USD 0.80/A$). Unlike most foreign currencies, the U.S. dollar is virtually a world currency. For example, one can pay for restaurant bills in Mexico City with U.S. dollars, but a restaurant bill in San Antonio cannot be paid for with

Mexican pesos. In fact, there reportedly is more U.S. currency in circulation in Russia than in the

United States.

A cross (or inferred) rate is the rate of exchange that is consistent with two (or more) other quoted rates of exchange. For example, if the rate of exchange between the U.S. dollar and

the British pound is USD 1.70/£ while the rate of exchange between the Mexican peso is

Mex$10.35/USD, then the rate of exchange between the Mexican peso and the British pound must be

Mex$/£ = USD 1.70/£ * Mex$ 10.35/USD

= Mex$17.595/£

If this relationship is NOT true, then currency traders will engage in lateral, or triangular, arbitrage and create the market forces that cause this relationship to hold.

For example, suppose that the quoted rate of exchange between the Mexican peso and the British pound is actually Mex$20.2/£ rather than the Mex$17.595/£ that the cross rate implies that it should be. The quoted rate of Mex$20.2/£ is too high . In any market, money is made by buying low and selling high. Thus, the quoted rate indicates that one should sell British pounds since Mex$20.2/£ is the peso price of a pound. (Note that a gallon of gas sells for $1.10 per gallon and hamburger sells for $2.59 per pound .)

In order to sell pounds, however, one must have pounds. There are two ways to buy pounds with Mexican pesos. One is to buy the British pounds directly at the quoted rate (which we have indicated is too high). The other way is to, first, buy U.S. dollars with Mexican pesos, and then to buy British pounds with the U.S. dollars. This is what we have essentially assumed when we determined the cross rate to be Mex$19.00/£ above.

Suppose we start with Mex$10,000 and buy U.S. dollars. Exchanging Mexican pesos for dollars at an exchange rate of Mex$10.35/USD will yield USD .

United States

USD 1.70/£

Great Britain

Mexico

Mex$ 10.35/USD Mex$20.2/£

To make money, then, we should sell pounds at the quoted price. If we start with US Dollars, we want to buy pounds with dollars, sell those pounds for pesos, and then buy dollars with pesos.

Beginning with USD 1,000

$ 1,000.00 divided by USD 1.70/£

£ 588.24 times 20.2 pesos/pound

11,882.45 pesos divided by 10.35 pesos/dollar

$ 1,148.06

Less:

Profit

$ 1,000.00 beginning amount

$ 148.06

The process of lateral arbitrage which we have just engaged in creates the market forces that will make the exchange rates adjust. When we bought pounds with dollars, we bid up the dollar price of a pound (the pound appreciates while the dollar depreciates). Similarly, when we sell the pounds for pesos, we increase the supply of pounds for sale for pesos and the peso value of the pound decreases. Finally, in buying U.S. dollars with pesos, we drive up the peso value of a dollar. This continues until all three exchange rates have adjusted and the exchange rates are in equilibrium so that the following equation holds:

USD 1.70/£ * Mex$ 10.35/USD < Mex$20.2/£

The Law of One Price

A primary economic principle is The Law of One Price. This states that identical goods will tend toward a single, worldwide price (assuming free movement of goods and adjusted for transportation costs, duties, etc.). Suppose gasoline is selling for $1.30/gallon in Austin while it sells for $1.05/gallon in San Antonio. Being enterprising entrepreneurs, we could go rent a big tanker truck and buy gasoline here in San Antonio for $1.05 per gallon and drive it to Austin to sell at $1.30 per gallon. As we buy more gasoline in San Antonio, we will drive the cost of a gallon up here. And as we sell more gasoline in Austin, we will drive down the cost of a gallon there. This will continue until the difference between the two prices is so small that it doesn’t cover the cost of the truck or the traveling expense.

The same phenomenon will occur between countries. In fact, at the moment gas in

Mexico is more expensive than gasoline in the U.S. People living in Nuevo Laredo will cross the bridge to buy gasoline in Laredo, but in order to do so they must buy dollars with their pesos and this affects the exchange rate. In equilibrium, the exchange rate will be such that the prices will be equivalent:

P d t

P f t

* X t where

P d t

= domestic price at time t

P f t

= foreign price at time t

X t

= direct exchange rate at time t

If this relationship holds in all periods, then

P d t

1

P f t

1

* X t

1

If we divide this last equation by the previous one, we get

P d t

1

P d t

P f t

P f t

1

*

X

X t

1 t

Next year’s price divided by this year’s price is equal to (1+inflation). By substituting and solving for next year’s exchange rate, we obtain

X t

1

X t

*

1

1

inflation inflation

f d

This equation is referred to a Purchasing Power Parity. Basically, it shows that exchange rates will change over time in order to reflect differences in rates of inflation between two countries since the Law of One Price must hold (or else arbitrage of products will occur that will force the exchange rate to the proper level through the buying and selling of currencies in order to buy the goods in one country and sell them in the other country).

Money can also be thought of as a commodity. The price of money is the rate of interest and the true price of money is the real , or inflation-adjusted, interest rate. The Fisher equation relates the nominal interest rate with the real rate of interest and inflation as

( 1

i nom

)

i real

) *( 1

inflation )

If the Law of One Price holds for money, then the real rate of interest should be the same in all countries. Then,

X t

1

X t

*

1

1

inflation inflation f d *

1

1

i real i real or

X t

1

X t

1

*

1

i d i f

This last equation is referred to as Interest Rate Parity. Essentially, it is stating that, after adjusting for exchange rate changes, interest rates are the same everywhere. For example, even though you can invest money in Mexico to earn a 20% rate of interest, the value of the peso should fall approximately 15% so that, after converting back to U.S. dollars, you earn the same

5% rate of interest you would get by investing in U.S. t-bills.

Just like other commodities, a futures market exists for foreign currencies. A futures contract, you will recall, is where you agree today to buy or sell a commodity at a fixed price at some future point in time. The futures contract price should be equal to the expected price in the future. If the contract price was consistently higher or lower, then speculators could make money by selling (or buying) at the contract price and then buying (or selling) at the market price. Such speculation will drive the contract prices toward an equilibrium level where, on average, no profit from speculation can be made.

The futures price on a foreign currency must be equal to the Interest Rate Parity condition above. If not, a person can engage in covered interest arbitrage which will create the market forces that will make the relationship hold. For example, suppose the rate of interest in the U.S. is

5% and the interest rate in England is 8%. If the current rate of exchange between U.S. dollars and British pounds is $1.60/£, then the forward rate of exchange should be

$ .

/ £ *

1.05

1.08

/ £

Suppose the quoted futures contract rate is $1.58/£. This is not consistent with the current rate of exchange and interest rates.

0 Britain 1

$1.60/£

0 U.S.

8%

1

$1.58/£

5%

Money can be moved in either direction today at the spot rate of exchange. Money can also be moved either from Britain to the U.S. or vice versa in one year at the futures rate of exchange.

Money can also be moved from today to next year or from next year to today in both the U.S. and

Great Britain. How? Money is moved to the future by lending. Future money is moved to the present by borrowing.

Since the quoted futures exchange rate of $1 .58/£ is higher than the computed rate of

$1.5556/£, we should be able to make money. As in any market, “buy low, sell high” rules and the quoted futures rate is high relative to what it should be, so we want to sell at the quoted price. Sell what? (Pounds since the quoted exchange rate is the dollar price of a pound.) If we are selling pounds in one year, then we are moving money from Britain to the U.S. Knowing the direction of that arrow dictates the direction of all of the other arrows:

0 Britain 1

$1.60/£

0 U.S.

8%

1

$1.58/£

5%

This diagram then says we should borrow money in the United States, convert it to pounds at the spot rate of exchange, invest the pounds in Britain, then convert the pounds back to dollars using a futures contract (which we lock into today) and pay off the loan.

Borrow

Pay off Loan

Invest in Britain

$100,000.00

Convert to pounds $1.60/£

£ 62,500.00

1.08

£ 67,500.00

Convert to dollars

$1.58/£

$106,650.00

105,000.00 ($100,000 * 1.05)

Profit $ 1,650.00

A profit of $1,650 can be made with no risk and requiring no equity investment. The market forces created through the covered interest arbitrage will result in bidding up the value of a pound in the spot market and driving down the value of a pound in the futures market until Interest Rate

Parity holds.

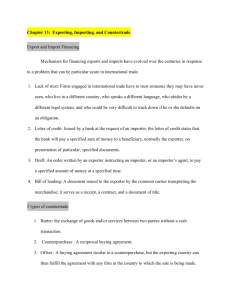

FINANCING FOREIGN TRADE

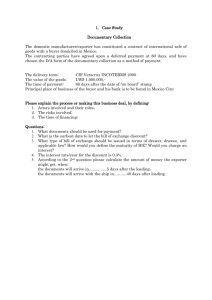

In order to facilitate international trade, a specialized mechanism has developed that benefits both exporters and importers. The exporter would naturally like to have cash in advance for a purchase rather than take the risk of non-payment from a firm in a foreign country. The importer, of course doesn’t want to pay until the goods are received and known to be in good condition. The Letter of Credit is the means by which the uncertainty of both the exporter and importer is reduced allowing foreign trade to occur.

Suppose a buyer in Taiwan wanted to purchase some machinery from a San Antonio manufacturer. The San Antonio seller will probably not be familiar with the individual buying company and will ask for a Letter of Credit (L/C). The Taiwan company will ask their bank in

Taiwan, say the Bank of Taipei, to issue a L/C guaranteeing payment for the goods. Since the

San Antonio seller probably doesn’t know anything about the Bank of Taipei, they would ask their bank here, say Bank of America, to confirm the L/C. Since Bank of America has probably done business with the Bank of Taipei, they would then provide a guarantee to the Bank of Taipei’s promise to pay.

The L/C would stipulate that a certain set of documents be produced before payment would be made. For example, it may require that a bill of lading showing that it had arrived in

Taipei be provided, as well as a consular invoice showing that customs duties had been paid.

Once the L/C is issued, the exporter can draw a draft (unsigned check) on the Bank of Taipei for the agreed upon price. Then the exporter can ship the equipment. When the equipment has reached Taipei and gotten through customs (as required by the terms of the L/C), the exporter presents the documents along with the draft to the Bank of Taipei. Once the Bank of Taipei has verified the authenticity of the documents, they will accept the draft and endorse it (marked

“accepted”) which makes the draft valid. These drafts are normally time drafts . That is, payment will be made on a specific date, say August 31. This puts a deadline on the exporter to comply with the terms by a specific deadline if they want to be paid. If the exporter has performed by, say

July 14, however, there is now a one and one-half month wait before the exporter is actually paid.

The exporter can sell the draft at a discount to Bank of America. This provides instant cash for the exporter. (It can also convert a draft denominated in won into U.S. dollars.) The Bank of

America packages the purchased drafts (banker’s acceptances since they have been “accepted” by the issuing bank) and sells them in the secondary money markets.

The advantage to the exporter is that they are now selling goods based on the promise of the Bank to pay them. It is up to the Bank of Taipei to collect from the Taiwan importer. In addition, with a L/C in hand, the San Antonio manufacturer can obtain some pre-export financing since they now have a contract for sale of the equipment. The Taiwan importer also gains since they don’t have to pay until the goods have actually arrived (or are on the way).

The following diagram illustrates the means by which a letter of credit functions in facilitating trade:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

5

San

Antonio

Exporter

8

Bank of

America

13

12

6

1

3

11

9

4

7

Order placed by importer

L/C requested by importer

L/C delivered to exporter, or

L/C delivered to exporter’s bank (usual)

Exporter’s bank notifies exporter of L/C

Order is shipped

Documents, draft delivered to exporter’s bank

Documents, draft delivered to importer’s bank (usual)

Exporter’s bank delivers documents to importer’s bank

Importer’s bank delivers documents to importer

Draft accepted, funds paid at maturity date

Exporter receives funds at maturity from importer’s bank

Exporter discounts draft, receives funds at maturity (usual)

Importer pays bank

Taiwan

Importer

14 10 2

Bank of

Taipei