Traumatic_brain_inju..

advertisement

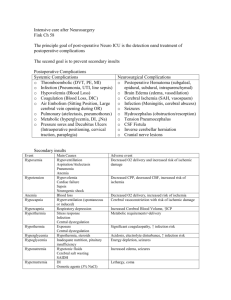

46 IX. Symptoms Traumatic Brain Injury Symptoms vary greatly depending on the severity of the head injury, but may include any of the following: Vomiting Lethargy Headache Confusion Paralysis Coma Loss of consciousness Dilated pupils Vision changes (blurred vision or seeing double, not able to tolerate bright light, loss of eye movement, blindness) Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (which may be clear or blood-tinged) coming out of the ears or nose Dizziness and balance problems Breathing problems Slow pulse Slow breathing rate, with an increase in blood pressure Ringing in the ears, or changes in hearing Cognitive difficulties Inappropriate emotional responses Speech difficulties Difficulty swallowing Body numbness or tingling Loss of bowel control or bladder control Diagnoses are been taken with: CT scan (CAT scan), X-ray, MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) Scan, Angiogram, ICP Monitor (registration intracranial pressure). Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 47 X. Intracranial pressure (ICP) and ICP monitoring A. Introduction Intracranial pressure, (ICP), is the pressure exerted by the cranium on the brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and the brain's circulating blood volume. ICP is a dynamic phenomenon constantly fluctuating in response to activities such as exercise, coughing, straining, arterial pulsation, and respiratory cycle. ICP is measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and, at rest, is normally less than 10-15 mmHg. Changes in ICP are attributed to volume changes in one or more of the constituents contained in the cranium. ICP monitoring has been established as an important treatment variable in severe non-penetrating brain injury, both in terms of prognosis and as a management variable, with intracranial hypertension clearly being associated with worse recovery and effective control of elevated ICP appearing to improve outcome To understand intracranial pressure, think of the skull as a rigid box. After brain injury, the skull may become overfilled with swollen brain tissue, blood, or CSF. The skull will not stretch like skin to deal with these changes. The skull may become too full and increase the pressure on the brain tissue. This is called increased intracranial pressure. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 48 B. Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP) a. Definition - Neurological dysfunction and death in TBI are due to: a. b. c. d. the brain injury itself, prolonged coma with its complications, infections from open wounds or basilar skull fractures, hydrocephalus from subarachnoid haemorrhage, and, most important, e. Increased intracranial pressure. - Intracranial is caused by: a. the added mass of epidural, subdural, and intracranial haematomas and b. Cerebral oedema which develops around large contusions, from diffuse vascular injury, and as a result of HIE. In infants, the skull can expand to some extent. After the sutures close, it is rigid. The brain and CSF are not compressible. Any increase in intracranial mass will first displace CSF into the spinal subarachnoid space. An increase of intracranial pressure above 4050 mm Hg will collapse brain capillaries resulting in global ischemia. ICP-monitor and registration Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 49 Raised intracranial pressure indicates an increase in the normal brain pressure. This can be due to an increase in cerebrospinal fluid pressure. It can also be due to increased pressure within brain matter because of lesions or swelling within the brain matter itself. An increase intracranial pressure is a severe medical problem. The pressure itself can be responsible for further damage to the central nervous system by causing compression of important brain structures and by restricting blood flow through blood vessels, which supply the brain. Many conditions can increase intracranial pressure. Common causes include: subdural haematoma hydrocephalus brain tumour hypertensive brain haemorrhage intraventricular haemorrhage meningitis encephalitis aneurysm rupture and subarachnoid haemorrhage status epilepticus stroke severe head injury Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 50 Measurement of ICP via intra-parenchymal, fibreoptic catheter intraventricular catheter, subarachnoid screw/bolt, epidural pressure sensor C. The Monroe-Kellie Hypothesis The pressure-volume relationship between ICP, volume of CSF, blood, and brain tissue, and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is known as the Monroe-Kellie doctrine or the Monroe-Kellie hypothesis. The Monroe-Kellie hypothesis states that the cranial compartment is incompressible, and the volume inside the cranium is a fixed volume. The cranium and its constituents (blood, CSF, and brain tissue) create a state of volume equilibrium, such that any increase in volume of one of the cranial constituents must be compensated by a decrease in volume of another. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 51 The principal buffers for increased volumes include both CSF and, to a lesser extent, blood volume. These buffers respond to increases in volume of the remaining intracranial constituents. For example, an increase in lesion volume (e.g. epidural hematoma) will be compensated by the downward displacement of CSF and venous blood. These compensatory mechanisms are able to maintain a normal ICP for any change in volume less than approximatly 100-120 mL. Monro-Kellie principle - regulation of ICP Normal ICP = 15mmHg Raised ICP =/ > 20mmHg A change in one compartment must be balanced by a change in another (blood, spinal fluid, brain tissue) BRAIN = TISSUE 80-85% CSF 5-12% BLOOD 3-7% Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 52 Intra-cranial compensation and his limits Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 53 D. Cerebral perfusion pressure Cerebral perfusion pressure, or CPP, is the net pressure of blood flow to the brain. It must be maintained within narrow limits because too little pressure could cause brain tissue to become ischemic (having inadequate blood flow), and too much could raise intracranial pressure (ICP). CPP can be defined as: CPP = MAP - ICP CPP is regulated by two balanced, opposing forces: Mean arterial pressure or MAP, the arithmetic mean of the body's blood pressure, is the force that pushes blood into the brain, and intracranial pressure is the force that keeps it out. Thus raising MAP raises CPP and raising ICP lowers it (this is one reason that increasing ICP in traumatic brain injury is potentially deadly). CPP, or MAP minus ICP, is normally between 70 and 90 mmHg in an adult human, and cannot go below 70 mmHg for a sustained period without causing ischemic brain damage. Children require pressures of at least 60 mmHg. CPP autoregulates between 80-100mmHg CPP <50mmHg loss autoregulation Physiological process decreased BP - cerebral blood vessels dilate increased BP - cerebral blood vessels constrict increase CO2 - cerebral blood vessels dilate decrease CO2 - cerebral blood vessels constrict decrease O2 - cerebral blood vessels dilate increased metabolism fever - increased flow decreased metabolism sedation- decreased flow Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 54 E. Autoregulation The brain maintains proper CPP through a process called autoregulation: to lower pressure, blood vessels in the brain called arterioles dilate, or widen, creating more room for the blood, and to raise pressure they constrict, or narrow. Thus, changes in the body's overall blood pressure do not normally alter cerebral perfusion pressure drastically. At their most constricted, blood vessels create a pressure of 150 mmHg, and at their most dilated the pressure is about 60 mmHg. When pressures are outside the range of 50 to 150 mmHg, the blood vessels' ability to autoregulate pressure through dilation and constriction is lost, and cerebral perfusion is determined by blood pressure alone, a situation called pressure-passive flow. Thus, hypotension (inadequate blood pressure) in a can result in severe cerebral ischemia in patients with conditions like brain injury, leading to a damaging process called the ischemic cascade. Other factors that can cause loss of autoregulation include free radical damage, nervous stimulation, and alterations in blood gas content. Amounts of carbon dioxide and oxygen in the blood affect constriction and dilation even in the absence of autoregulation: excess carbon dioxide can dilate blood vessels up to 3.5 times their normal size, lowering CPP, while high levels of oxygen constrict them. Blood vessels also dilate in response to low pH. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 55 Thus, when activity in a given region of the brain is heightened, the increase in CO2 and H+ concentrations causes cerebral blood vessels to dilate and deliver more blood to the area to meet the increased demand. In addition, stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system raises blood pressure and blocking it lowers pressure. F. Increased ICP One of the most damaging aspects of brain trauma and other conditions, directly correlated with poor outcome, is an elevated intracranial pressure ICP is very likely to cause severe harm if it goes past 40 mmHg in an adult. Even intracranial pressures between 25 and 30 mm Hg are usually fatal if prologed, except in children, who can tolerate higher pressures for longer times. Most commonly due in head injury to intracranial hematoma or cerebral edema, an increase in pressure can crush brain tissue, shift brain structures, contribute to hydrocephalus, cause the brain to herniate, and restrict blood supply to the brain, leading to an ischemic cascade (Graham and Gennareli, 2000). G. Pathophysiology The cranium and the vertebral body, along with the relatively inelastic dura, form a rigid container, such that the increase in any of its contents --- brain, blood, or CSF --- will increase the ICP. In addition, any increase in one of the components must be at the expense of the other two, a relationship known as the Monroe-Kelly doctrine. Small increases in brain volume does not lead to immediate increase in ICP because of the ability of the CSF to be displaced into the spinal canal, as well as the slight ability to stretch the falx cerebri between the hemispheres and the tentorium between the hemispheres and the cerebellum. However, once the ICP has reached around 25 mmHg, small increases in brain volume can lead to marked elevations in ICP. Traumatic brain injury is a devastating problem with both high mortality and high subsequent morbidity. Injury to the brain occurs both at the time of the initial trauma (the primary injury) and subsequently due to ongoing cerebral ischemia (the secondary injury). Cerebral edema, hypotension, and axonal hypoxic conditions are well recognized causes of this secondary injury. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 56 In the intensive care unit raised intracranial pressure (intracranial hypertension) is seen frequently after a severe diffuse brain injury and leads to cerebral ischemia by compromising cerebral perfusion. The difference between the ICP and the mean arterial pressure within the cerebral vessels is termed the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP)(cerebral perfusion pressure is calculated by subtracting the intracranial pressure from the mean arterial pressure CPP=MAP-ICP), the amount of blood able to reach the brain. One of the main dangers of increased ICP is that it can cause ischemia by decreasing cerebral perfusion pressure. Once the ICP approaches the level of the mean systemic pressure, it becomes more and more difficult to squeeze blood into the intracranial space. The body’s response to a decrease in CPP is to raise blood pressure and dilate blood vessels in the brain. This results in increased cerebral blood volume, which increases ICP, lowering CPP further and causing a vicious cycle. This results in widespread reduction in cerebral flow and perfusion, eventually leading to ischemia and brain infarction. Increased blood pressure can also make intracranial hemorrhages bleed faster, also increasing ICP. Highly increased ICP, if caused by a one-sided space-occupying process (eg. an haematoma) can result in midline shift, a dangerous condition in which the brain moves toward one side as the result of massive swelling in a cerebra hemisphere. Midline shift can compress the ventricles and lead to buildup of CSF.[Prognosis is much worse in patients with midline shift than in those without it. Another dire consequence of increased ICP combined with a space-occupying process is brain herniation (usually uncal or cerebellar), in which the brain is squeezed past structures within the skull, severely compressing it. If brainstem compression is involved, it may lead to decreased respiratory drive and is potentially fatal. This herniation is often referred to as "coning". Major causes of morbidity due to increased intracranial pressure are due to global brain infarction as well as decreased respiratory drive due to brain herniation. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 57 H. Intracranial Hypertension Minimal increases in ICP due to compensatory mechanisms are known as stage 1 of intracranial hypertension. When the lesion volume continues to increase beyond the point of compensation, the ICP has not other resource, but to increase. Any change in volume greater than 100-120 mL would mean a drastic increase in ICP. This is stage 2 of intracranial hypertension. Characteristics of stage 2 of intracranial hypertension include compromise of neuronal oxygenation and systemic arteriolar vasoconstriction to increace MAP and CPP. Stage 3 of the intracranial hypertension is characterised by a sustained increased ICP, with dramatic changes in ICP with small changes in volume. In stage 3, as the ICP approaches the MAP, it becomes more and more difficult to squeeze blood into the intracranial space. The body’s response to a decrease in CPP is to raise blood pressure and dilate blood vessels in the brain. This results in increased cerebral blood volume, which increases ICP, lowering CPP further and causing a vicious cycle. This results in widespread reduction in cerebral flow and perfusion, eventually leading to ischemia and brain infarction. Neurologic changes seen in increased ICP are mostly due to hypoxia and hypercapnea and are as follows: decreased LOC, Cheyne-Stokes respirations, hyperventilation, sluggish dilated pupils and widened pulse pressure. I. Causes of increased ICP Causes of increased intracranial pressure can be classified by the mechanism in which ICP is increased: a) Mass effect such as brain tumor, infarction with edema, contusions, subdural or epidural hematoma, or abscess all tend to deform the adjacent brain. b) Generalized brain swelling can occur in ischemic-anoxia states, acute liver failure, hypertensive encephalopathy, pseudotumor cerebri, hypercarbia, and Reye hepatocerebral syndrome. These Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 58 conditions tend to decrease the cerebral perfusion pressure but with minimal tissue shifts. c) Increase in venous pressure can be due to venous sinus thrombosis, heart failure, or obstruction of superior mediastinal or jugular veins. d) Obstruction to CSF flow and/or absorption can occur in hydrocephalus (blockage in ventricles or subarachnoid space at base of brain, e.g., by Arnold-Chiari malformation), extensive meningeal disease (e.g., infectious, carcinomatous, granulomatous, or hemorrhagic), or obstruction in cerebral convexities and superior sagittal sinus (decreased absorption). e) Increased CSF production can occur in meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or choroid plexus tumor. J. Signs and symptoms of increased ICP In general, symptoms and signs that suggest a rise in ICP including headache, nausea, vomiting, ocular palsies, altered level of consciousness, and papilla oedema. If papilla oedema is protracted, it may lead to visual disturbances, optic atrophy, and eventually blindness. In addition to the above, if mass effect is present with resulting displacement of brain tissue, additional signs may include pupillary dilatation, abducens (CrN VI) palsies, and the Cushing's triad. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 59 Cushing's triad involves an increased systolic blood pressure, a widened pulse pressure, bradycardia, and an abnormal respiratory pattern.In children, a slow heart rate is especially suggestive of high ICP. Irregular respirations occur when injury to parts of the brain interfere with the respiratory drive. Cheyne-Stokes respiration, in which breathing is rapid for a period and then absent for a period, occurs because of injury to the cerebral hemispheres or diencephalon. Hyperventilation can occur when the brain stem or tegmentum is damaged. As a rule, patients with normal blood pressure retain normal alertness with ICP of 25 to 40 mmHg (unless there's concurrent tissue shift). Only when ICP exceeds 40 to 50 mmHg do CPP and cerebral perfusion decrease to a level that result in loss of consciousness. Any further elevations will lead to brain infarction and brain death. In infants and small children, the effects of ICP differ due to the fact that their cranial sutures have not closed. In infants, the fontanels, or soft spots on the head where the skull bones have not yet fused, bulge when ICP gets too high. Gunshot wound left fronto-parietal region entrance wound Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 60 Intracerebellar haemorrhage shown by CT scan K. Treatment of increased ICP In addition to management of the underlying causes, major considerations in acute treatment of increased ICP relates to the management of stroke and cerebral trauma. One of the most important treatments for high ICP is to ensure adequate airway, breathing, and oxygenation, since inadequate oxygen levels or excess carbon dioxide cause cerebral blood vessels to dilate and ICP to rise. Inadequate oxygen also forces brain cells to produce energy using anaerobic metabolism, which produces lactic acid and lowers pH, which dilates blood vessels. On the other hand, blood vessels constrict when carbon dioxide levels are below normal, so hyperventilating a patient with a ventilator or bag valve mask can temporarily reduce ICP but limits blood flow to the brain in a time when the brain may already be ischemic. Artificially ventilating a patient at a fast rate used to be a standard part of head trauma treatment because of its ability to rapidly lower ICP, but the chance of developing ischemia was later recognized to be too much of a risk. Furthermore, the brain adjusts to the new level of carbon dioxide after 48 to 72 hours of hyperventilation, which could cause the vessels to rapidly dilate if carbon dioxide levels were returned to normal too quickly. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 61 Now hyperventilation is used when signs of brain herniation are apparent because the damage herniation can cause is so severe that it may be worthwhile to constrict blood vessels even if doing so reduces blood flow. Another way to lower ICP is to raise the head of the bed, allowing for venous drainage. A side effect of this is that it could lower pressure of blood to the head, resulting in inadequate blood supply to the brain. Another simple method used to lower ICP (particularly in trauma cases) is to loosen neck collars and clothing. This method is more useful is the patient is sedated and thus movement is minimal. Sandbags may be used to further limit neck movement. In the hospital, blood pressure can be artificially raised in order to increase CPP, increase perfusion, oxygenate tissues, remove wastes and thereby lessen swelling. Since hypertension is the body's ways of forcing blood into the brain, medical professionals do not normally interfere with it when it is found in a head injured patient. When it is necessary to decrease cerebral blood flow, MAP can be lowered using common antihypertensive agents such as calcium channel blockers. Struggling can increase metabolic demands and oxygen consumption, as well as increasing blood pressure. Thus children may be paralyzed with drugs if other methods for reducing ICP fail. Paralysis allows the cerebral veins to drain more easily, but can mask signs of seizures, and the drugs can have other harmful effects. Pain is also treated to reduce agitation and metabolic needs of the brain, but some pain medications may cause low blood pressure and other side effects. Intracranial pressure can be measured by means of a lumbar puncture or continuously with intracranial transducers (only used in neurosurgical intensive care). A catheter can be surgically inserted into one of the brain's lateral ventricles and can be used to drain CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) in order to decrease ICP's. This type of drain is known as an EVD (extra-ventricular drain).In rare situations when only small amounts of CSF are to be drained to reduce ICP's, drainage of CSF via lumbar puncture can be used as a treatment. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 62 BLOOD-BRAIN BARRIER The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is the specialized system of capillary endothelial cells that protects the brain from harmful substances in the blood stream, while supplying the brain with the required nutrients for proper function. Unlike peripheral capillaries that allow relatively free exchange of substance across / between cells, the BBB strictly limits transport into the brain through both physical (tight junctions) and metabolic (enzymes) barriers. Thus the BBB is often the rate-limiting factor in determining permeation of therapeutic drugs into the brain. Additionally, BBB breakdown is theorized to be a key component in central nervous system (CNS) associated pathologies. BBB investigation is an ever growing and dynamic field studied by pharmacologists, neuroscientists, pathologists, physiologists, and clinical practitioners. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 63 L. Management ICP - Prevention vasospasm calcium channel blocker Nimodipine - Prevention seizure phenytoin - Treatment seizure diazepam, lorazepam, calcium, barbiturates … - Intracranial mass lesions surgical decompression - CSF retention - acute CSF drainage via ventricular drain chronic CSF drainage via ventriculo-peritoneal shunt reducing CSF formation frusemide (Lasix) by interfering chloride transport acetazolamide (Diamox) by interfering carbonic anhydrase system - Cerebral oedema Oedema due to hypoxia A: due to vasogenic breakdown in BBB (Blood brain barrier) or cytotoxic where BBB intact - fluid restriction (not always) - osmolar diuretics (mannitol) reduction cerebral B: oedema via intact BBB plus additional renal excretion - loop diuretics (frusemide can prolong osmotic effect of mannitol /ethacrynic acid) - steroids (poor research support) Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 64 - Cerebral blood volume - Maintain MAP within limits cerebral autoregulation - beta blockade post head injury - Head up position 30 degree, neck alignment and minimal hip flexion - Sedation, neuromuscular blockade - avoiding large increases in CVP/intrathoracic pressure - Hyperventilation PaCO2 35 mmHg - Cerebral vasoconstriction - thiopentone, barbiturate coma M. Decompressive craniectomy Craniotomeis are holes drilled in the skull to remove intracranial hematomas or relieve pressure from parts of the brain. As raised ICP's may be caused by the presence of a mass, removal of this via craniotomy will decrease raised ICP's. CASE: Abstract (Ref.:Sherif El-Watidy, Abdelazeem El-Dawlatly, Zain A. Jamjoom, Essam ElGamal: Use of Transcranial Cerebral Oximeter as Indicator for Bifrontal Decompressive Craniectomy. Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2004. Volume 8 Number 2.) Objectives: The timing of bifrontal decompressive craniectomy (BDC) in patients with intractable intracranial hypertension (IH) is crucial, and the decision to do surgery is based primarily on invasive neuromonitoring. In this report the authors show the efficacy of a non-invasive, near infrared transcranial cerebral oximeter (TCCO) in the management of a patient with post-traumatic IH. Clinical Presentation: A 14-year-old male patient who had severe head injury following road traffic accident (RTA). His Glasgow Come Score (GCS) was 6/15. Brain computerized tomography (CT) scan showed multiple brain contusions and diffuse brain edema. He developed a state of IH that did not respond to standard medical treatment. We have used TCCO for neuromonitoring, its readings showed marked difference between the two cerebral hemispheres and this correlated well with the clinical and radiological findings. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 65 Intervention: Because of the decreasing trend of cerebral oxygen saturation and pupillary changes (anisocoria) BDC was performed. The timing of surgery was appropriate as no brain infarction occurred. Following surgery, TCCO readings were normal and the patient recovery was dramatic and relatively quick. Conclusion: TCCO may be an efficient Neuromonitoring tool in determining the time for surgical interference in patients with IH following RTA. Infrared transcranial cerebral oximeter The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and received standard treatment for such cases: sedation and muscle relaxation, normothermia, mild hyperventilation to keep PCO2 between 30-35 mmHg, mannitol, and dopamine infusion was titrated to keep the mean BP 90 mmHg. TCCO neuromonitoring was used which showed difference in the initial readings from both cerebral hemispheres: left 57% and right 72%. The patient responded to mannitol and the pupils came down to 2mm and became equal. We decided to continue the same medical treatment and postpone surgical decompression. TCCO readings in the first 6 hours were more or less similar to the initial readings with more saturation in the right hemisphere. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 66 About 8 hours after admission there was an attack of bradycardia associated with reduced oxygen saturation from cerebral hemispheres, right 65% and left 50%. Repeat CT of the brain scan showed more apparent brain contusions surrounded with oedema, more swelling of the left hemisphere with more shift of midline structures, and complete obliteration of the basal cisterns. (see Fig. 2) Immediately following CT scan, both pupils blown up with the left bigger than right. An extra bolus of mannitol was given and the patient was quickly taken to the theatre to undergo BDC. The patient head was kept slightly elevated on a horseshoe headrest. The bicoronal skin incision runs at a variable distance behind the coronal suture, the skin was raised together with the pericranium, and the temporalis fascia in one flap. The temporalis muscle was detached and retracted posteriorly and inferiorly on both sides. Two burr holes were done over the midline, the first one above the nasion (high enough to avoid opening the frontal air sinus), and the second one at variable distance behind the coronal suture (depending on the amount of bony decompression). Multiple burr holes were then made along the planned line of bone cuts. We use either craniotome or Gigli saw to cut the bone. After elevating the bone flap we performed wide bilateral subtemporal bony decompression. The dura was opened on both sides of the superior sagittal sinus which was cut between ligatures together with the falx cerebri to allow simultaneous external herniation of both hemispheres without the risk of brain incarceration. Dural cuts extend laterally to the base of the middle cranial fossa and posteriorly parallel to the sinus. We closed skin in two layers leaving a subgaleal drain. Due to reflection of skin flap it is technically difficult to continue monitoring cerebral oxygen saturation during surgery. Immediately following decompressive craniectomy, the pupils came down to 2 mm and became equal but not reactive to light. The cerebral oxygen saturation showed dramatic improvement (right hemisphere 85% and left one 76%). Mannitol and dopamine were continued for three more days and then tapered off. Nasogastric tube feeding was started on the second day and PCO2 was maintained around 35 mmHg. Neurologic recovery following BDC was quick and dramatic. Two weeks later the trachea was extubated. The patient was able to open his eyes spontaneously and obeyed verbal commands at times. GCS was 9-10/15 and his pupils were equal and reactive to light. He had transient right arm weakness and dysphasia for three weeks. Follow-up CT brain scans (Fig 3, 4) showed the resolution of brain contusions, brain enema, and absence of brain infarction (Fig 5). Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 67 Fig. 1 Fig.2 Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 68 Fig.3 Fig.4 Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 69 Fig.5 A decompressive craniectomy is a drastic treatment for increased ICP is, in which a part of the skull is removed and the dura mater is expanded to allow the brain to swell without crushing it or causing herniation. The section of bone removed, known as a bone flap, can be stored in the patient's abdomen (or in the freezer) and resited back to complete the skull once the acute cause of raised ICP's has resolved. N. Complications and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) 1. Postconcussion Syndrome Within days to weeks of a head injury approximately 40 percent of TBI survivors develop troubling symptoms called postconcussion syndrome (PCS). A person need not have suffered a concussion or loss of consciousness to develop the syndrome and many people with mild TBI suffer from PCS. Symptoms include headache, dizziness, vertigo (a sensation of spinning around or of objects spinning around the person), memory problems, trouble concentrating, sleeping problems, restlessness, irritability, apathy, depression, and anxiety. These symptoms may last for a few weeks after the head injury. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 70 The syndrome is more common in individuals who had psychological symptoms, such as depression or anxiety, before the injury. Treatment for PCS may include medicines for pain and psychological conditions, and counselling to develop coping skills. 2. Seizures About 25 percent of patients with brain contusions or haematomas and about 50 percent of patients with penetrating head injuries will develop seizures within the first 24 hours of the injury. These seizures generally stop within a week. Doctors typically only treat these seizures if they continue beyond a week. Seizures occurring more than one week after injury are referred to as post-traumatic epilepsy and are treated with medications. The medications may need to be taken by the survivor for months or years following the injury. 3. Hydrocephalus Our brains continually produce and drain a fluid called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). When the brain is injured the drainage of CSF may be affected and CSF may build up. This condition is called hydrocephalus. The build-up of fluid can lead to increased pressure in the brain. Hydrocephalus may begin during the early stages of TBI but not be apparent until much later. However, it usually is diagnosed within the first year after the injury. Symptoms can include a decreased level of consciousness, changes in behaviour, lack of coordination or balance, and loss of the ability to hold urine. Treatment may include draining CSF through a small plastic tube called a shunt. The shunt typically runs under the skin from the head to the abdomen, where the fluid drains and is reabsorbed by the body. 4. Leakage of CSF Skull fractures can tear the membranes that cover the brain, leading to leakage of CSF. While the leaking fluid may be trapped between the membranes that surround the brain, it may also leak out of the nose or ears. Surgery may be necessary to repair the fracture and stop the leakage. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 71 5. Infections Tears that let CSF out of the brain cavity can also allow air and bacteria into the cavity. An infection of the membrane around the brain is called meningitis and is a dangerous complication of TBI. Most infections develop within a few weeks of the initial trauma and result from skull fractures or penetrating injuries. Standard treatment includes antibiotics and sometimes surgery to remove the infected tissue. 6. Damaged Blood Vessels in the Brain Surgery is necessary to repair an injured blood vessel responsible for a hemorrhagic stroke. Ischemic strokes can be treated with a drug that dissolves clots (a “thrombolytic” drug) if the stroke is diagnosed within a few hours of the beginning of symptoms and there is no evidence of bleeding in the brain. The drug can be given intravenously or through a tube (catheter) that is inserted into an artery in the groin and then advanced to the brain and then into the clogged artery, where the medication is administered through the catheter. Administering the drug through a catheter at the site of the clot has a higher chance of success than intravenous medication but is usually only performed at stroke centres by a team of specialists that can be rapidly assembled twenty-four hours a day. 7. Cranial Nerve Injuries Cranial nerves are nerves running from the brain through openings in the skull and to areas in the head such as the eyes, ears, and face. Skull fractures, especially at the base of the skull, can injure cranial nerves. The seventh cranial nerve, called the facial nerve, is the most commonly injured cranial nerve in TBI. An injured facial nerve can result in paralysis of facial muscles. When facial muscles are paralyzed, facial expressions such as smiling will not be symmetrical. Nerve injuries may heal spontaneously. If they do not, surgery may, in certain circumstances, be able to restore nerve function. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 72 8. Pain Pain is a common symptom of TBI and can be a significant complication for conscious patients in the period immediately following a TBI. Headache is the most common type of pain, but other kinds of pain can also occur. 9. Complications for Unconscious Patients Serious complications for patients who are unconscious, in a coma, or in a vegetative state include bed or pressure sores of the skin, repeated bladder infections, pneumonia or other life-threatening infections, and the failure of multiple organs, such as the kidneys, lungs, and heart. 10. General Trauma When a TBI occurs there is usually trauma to not only the brain but other parts of the body as well. These injuries require immediate and specialized care and can complicate treatment of and recovery from the TBI. O. Disabilities from a TBI. Disabilities resulting from a TBI depend upon the severity of the injury, the location of the injury, and the age and general health of the individual. 1. Cognitive Disabilities “Cognition” describes the processes of thinking, reasoning, problem solving, information processing, and memory. Most patients with severe TBI, if they recover consciousness, suffer some cognitive disability. People with moderate to severe TBI have more problems with cognitive deficits than survivors with mild TBI, but a history of several mild TBIs (for example, a football player) may have a cumulative effect. Recovery from cognitive deficits is greatest within the first six months after the injury and is usually more gradual after that. Most improvements can be expected within two years of the injury. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 73 2. Memory The most common cognitive impairment among severely head-injured survivors is memory loss, characterized by some loss of older memories and the partial inability to retain new memories. Some of these patients may experience post-traumatic amnesia, which can involve the complete loss of memories either before or after the injury. 3. Concentration and attention Many survivors with even mild to moderate head injuries who experience cognitive deficits become easily confused or distracted and have problems with concentration and attention. 4. Executive functioning Many individuals with a mild to moderate TBI also have problems with higher level, so-called “executive” functions, such as planning, organizing, abstract reasoning, problem solving, and making judgments. This disability may make it difficult to return to the same job or school setting the individual was in before the injury. 5. Language and communication Language and communication are frequent problems for TBI survivors. Some individuals have trouble recalling words and speaking or writing in complete sentences (called non-fluent aphasia). They may speak in broken phrases and pause frequently. They are usually aware of what is happening and may become extremely frustrated. Other survivors may speak in complete sentences and use correct grammar but for the listener the speech is pure gibberish, full of invented or meaningless words (called fluent aphasia). TBI survivors with this problem are often unaware that they make little sense and become angry with others for not understanding them. Other survivors can think of the appropriate language but cannot easily speak the words because they are unable to use the muscles needed to form the words and produce the sounds (called dysarthria). Speech is slow, slurred, and garbled. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 74 6. Impairment of the Senses Many TBI survivors have problems with one of the five senses, especially vision. They may not register what they are seeing or may be slow to recognize objects. Some individuals develop tinnitus, a ringing or roaring in the ears. Others may develop a persistent bitter taste in the mouth or complain of a constant foul smell. Some TBI survivors feel persistent skin tingling, itching, or pain. Although rare, these conditions are hard to treat. 7. Impairment of Hand-Eye Coordination TBI survivors often have difficulty with hand-eye coordination. Because of this, they may be prone to bumping into or dropping objects or may seem generally unsteady. They may have difficulty driving a car, working complex machinery, or playing sports. 8. Emotional and Behavioural Problems Most TBI survivors have some emotional or behavioural problems. Family members often find that personality changes and behavioural problems are the most difficult disabilities to deal with. Emotional problems can include depression, apathy, anxiety, irritability, anger, paranoia, confusion, frustration, agitation, difficulty sleeping, and mood swings. Problem behaviours may include aggression and violence, impulsiveness, loss of inhibitions, acting out, being uncooperative, emotional outbursts, childish behaviour, impaired selfcontrol, impaired self awareness, inability to take responsibility or accept criticism, being concerned only with oneself, inappropriate sexual activity, and alcohol or drug abuse. Sometimes TBI survivors stop maturing emotionally, socially, or psychologically after the trauma, which is a particularly serious problem for children and young adults. Many TBI survivors who show psychiatric or behavioural problems can be helped with medication and psychotherapy. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 75 P. Other Long-Term problems associated with TBI? 1. Alzheimer's Disease (AD) AD is a degenerative disease in which the individual suffers progressive loss of memory and other cognitive abilities. Recent research suggests an association between head injury in early adulthood and the development of AD later in life; the more severe the head injury, the greater the risk of developing AD. Some evidence indicates that a head injury may interact with other factors to trigger the disease and may hasten the onset of the disease in individuals already at risk. 2. Parkinson's disease and other motor problems Parkinson's disease may develop years after TBI if the part of the brain called the basal ganglia was injured. Symptoms of Parkinson's disease include tremors, rigidity or stiffness, slow movement or inability to move, a shuffling walk, and stooped posture. Despite many scientific advances in recent years, no cure has yet been discovered and the disease progresses in severity. Other movement disorders that may develop after TBI include tremor, uncoordinated muscle movements, and sudden contractions of muscles. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 76 The consequences of brain damage are as follows: Behavioral/ Personality CognitiveIntellectual Emotional PerceptualPerceptual Motor Social Disabilities 1. Lack of goal-directed behavior 1. Disorders of consciousness 1. Apathy 1. Reduced motor speed 1. Social withdrawal 2. Lack of initiation 2. Disorientation 2. Impulsivity 2. Reduced eye-hand coordination 2. Lack of acceptance by family associates 3. Poor self-image, reduced self worth 3. Memory deficits 3. Irritability 3. Poor depth perception 3. Family role identity problems 4. Spatial disorientation 4. Marital stress 5. Poor figure-ground perception 5. Sexual dysfunction 6. Auditory perceptual deficits 6. Inappropriate social behaviors 7. Anosognosia 7. Loss of leisure skills and interests 4. Denial of disability or its consequences 5. Aggressive behavior 4. Decreased abstraction 4. Aggressiveness 5. Decreased learning abilities 5. Anxiety 6. Language-communication deficits 6. Depression 6. Childlike behavior 7. Emotional liability 7. General intellectual deficits 7. Bizarre, psychotic ideation and behavior 8. Silliness 8. Deficits in processingsequencing information 8. Loss of sensitivity and concern for others: selfishness 9. Dependency, passivity 10. Indecision 11. Indifference 8. Autotopagnosia 8. Need for structure 9. Tactile, auditory, visual neglect 9. Illogical thoughts. 9. Legal infractions 10. Apraxias 10. Poor judgment 10. Dependence in legal-business affairs 11. Poor quality control 12. Inability to make decisions 12. Slovenliness 13. Poor initiative 11. Unemployment-financial difficulties 12. Inability to profit from experience 13. Sexual disturbances 14. Drug, alcohol abuse 14. Verbal motor perseveration 15. Confabulation 16. Difficulty on generalization 17. Short attention span 18. Distractibility 19. Fatigability 20. Perplexity 21. Dyscalculia Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 77 Conclusions Of all types of injury, those to the brain are among the most likely to result in death or permanent disability. Brain injury is the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of seizure disorders. Every year, approximately millions of people sustain a head injury. Most of these injuries are minor because the skull provides the brain with considerable protection. The symptoms of minor head injuries usually go away on their own. More than half a million head injuries a year, however, are severe enough to require hospitalization. Learning to recognize a serious head injury, and implementing basic first aid, can make the difference in saving someone's life. In patients who have suffered a severe head injury, there is often one or more other organ systems injured. A head injury is any trauma that leads to injury of the scalp, skull, or brain. These injuries can range from a minor bump on the skull to a devastating brain injury. Head injury can be classified as either closed or penetrating. In a closed head injury, the head sustains a blunt force by striking against an object. In a penetrating head injury, an object breaks through the skull and enters the brain. (This object is usually moving at a high speed like a windshield or another part of a motor vehicle.) A concussion is a type of closed head injury that involves the brain. About 25 percent of patients with brain contusions or haematomas and about 50 percent of patients with penetrating head injuries will develop seizures within the first 24 hours of the injury. These seizures generally stop within a week. Doctors typically only treat these seizures if they continue beyond a week. Seizures occurring more than one week after injury are referred to as posttraumatic epilepsy and are treated with medications. Cognitive symptoms arising out of the head injury/brain damage may include communication problems, reduced ability to process information, memory loss, impaired judgment, spatial disorientation, and concentration problems. Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016 78 The physical problems caused by head injury/brain damage can include pain, seizures, speech impairment, visual impairment, problems with balance, sleeplessness, fatigue, and loss of taste and smell. The emotional problems resulting from head injury/brain damage may include inability to initiate activities, anxiety, depression, mood swings and difficulty in completing tasks without reminders, impulsive behaviour, and feelings of agitation. Traumatic brain injury can range from relatively mild to catastrophically severe depending on multiple factors including degree of force, multiple trauma, neurological complications, and timeliness of emergency medical treatment. ---------------- Traumatic Brain Injury – A. Houtman – HHRoeselare Belgium – Version 2 - 08/03/2016