Mohit Agrawal (1.9) The Western Heritage, 8th Edition, by Kagan

advertisement

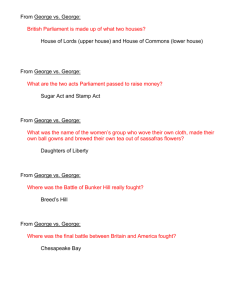

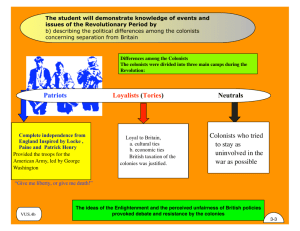

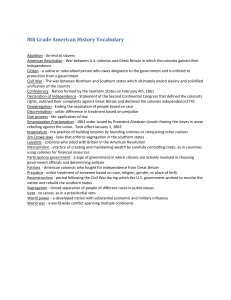

Mohit Agrawal (1.9) The Western Heritage, 8th Edition, by Kagan, Ozment, and Turner Chapter 17-Mid-Century War and Rebellion Introduction During the 17th and 18th centuries, European maritime nations established overseas empires and set up trading monopolies within them in an effort to magnify their own economic strength. The mid-18th century witnessed a renewal of European warfare on a worldwide scale. Austria and Prussia fought for dominance in central Europe while GB and France dueled for commercial and colonial supremacy. Overall, Prussia and GB won. Prussia became a great land power and GB a colonial/naval power. The expense of the wars led the nations to reconstruct their policies of taxation and finance. The effects of this reconstruction were felt on the continent (and abroad) for the remainder of the century. Mid-Eighteenth Century Wars The state system of the mid 18th century was quite unstable and tended to lead the major European powers into periods of prolonged war. The statesmen of the period welcomed (or at least didn’t avoid) warfare as a means to further national interests. Civilian populations were rarely drawn deeply into the conflicts; they were fought by professional armies and navies. Wars didn’t really affect domestic politics or social issues. Moreover, peace was not the goal. Instead, it was just a time to regroup until the next war. The two main areas of conflict were over overseas territories and over land in central/eastern Europe. Wars over each area sometimes overlapped (and became the first world wars). The War of Jenkins’s Ear Tensions over Spanish attempts to cut off English smuggling in the West Indies came to a climax in the late 1730s. The Treaty of Utrecht gave GB the right (asiento) to furnish slaves to the Spanish territories. Britain also gained the right to send one ship a year to trade with these territories. Once the door was cracked open, smuggling of goods began to increase exponentially. One smuggling ship captained by Robert Jenkins was stopped by the Spanish in 1731. A fight broke out and the Spanish cut off Jenkins’s ear. He kept it preserved in a bottle of brandy. In 1738, as tension was building in Britain, Jenkins appeared before the British Parliament and brandished his ear as an example of Spanish atrocities to British merchants. England and Spain went to war in 1739. It was a relatively minor effort. Britain captured the important port city of Portobello, but the two countries’ navies were deadlocked. The war eventually merged with the larger War of Austrian Succession. This war became the opening encounter to a series of European wars fought across the world until 1815. The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) In Dec 1740, after being king of Prussia for fewer than 7 months, Frederick II seized the Austrian province of Silesia in eastern Germany. This shattered the Pragmatic Sanction and upset the balance of power set up by the Treaty of Utrecht. Maria Theresa Preserves the Hapsburg Empire Mohit Agrawal (2.9) Instead of the Prussian attack leading to internal division and crumbling of the Austrian empire, Maria Theresa kept the thing together (though she did lose Silesia). Maria Theresa won loyalty and support from her various subjects not merely through her heroism, but by granting new privileges to the nobility. She also recognized the importance of Hungary and gave them much local autonomy. Thus, her achievement was at considerable cost to the power of the central monarchy. Hungary would from now on be a source of friction for the Habsburg monarchs. France Draws Great Britain into the War What united the two wars (Austria v Prussia and GB v Spain) was France. A group of aggressive court aristocrats compelled the elderly Cardinal Fleury to put aside his plans to attack GB and instead to support the Prussians against the hated Austrians. Aid to Prussia was dangerous because it strengthened a new German state which could potentially threaten France (which it did later). Also, to support Prussia, France had aimed at the Austrian Netherlands (now Belgium). GB did not want France to get Belgium, so GB went to war with France. In 1744, the British-French conflict expanded beyond the Continent, as France decided to support Spain in the New World. This, of course, severely divided French military capabilities. France should have forgotten about Austria (the Prussians could take care of them anyway) and should have concentrated on GB. It didn’t, however, and this is one of the clearest causes of the upcoming French Revolution. The War of Austrian Succession ended in stalemate in 1748 with the Treaty of Aix-laChapelle. Prussia got Silesia, but nothing else changed. The treaty was a truce rather than a permanent peace. The “Diplomatic Revolution” of 1756 Before war broke out again, a dramatic shift of alliances took place. In Jan 1756, Prussia and GB signed the Convention of Westminster, a defensive pact for northern Europe. GB, the once ally of Austria, now joined Prussia (English king was north German, they complemented each other with army and navy, and they were in a common geographic area) France felt shunned over this development, and in May of 1756 signed a defensive pact with Austria (this was smart for France b/c Prussia was the big power on the Continent now, not Austria, so Prussia needed to be held back some how) The Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) France and Britain had never really stopped fighting in the New World, even after the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. Their settlers kept fighting in the Ohio River Valley (remember that the Virginian plantation owners were itching to move out west over the Appalachians, and eventually sent out George Washington). This precipitated the French and Indian War in the colonies. Prussia, however, expands the war onto the Continent. Frederick the Great Opens Hostilities In Aug 1756 Frederick II invaded Saxony. He saw this as a preemptive move against the French and Austrians who wanted to attack him. Prussia’s actions, however, actually made France and Austria try harder against Prussia than they would have originally. Mohit Agrawal (3.9) Sweden, Russia, and the smaller HRE states joined the French/Austrian side. Frederick II was a stubborn/brilliant leader during the war. He earned the name “Great” because of it. Two things saved Prussia. One was that GB gave it financial aid. Secondly, Empress Elizabeth of Russia died in 1762 and Tsar Peter III, who was an avid admirer of Frederick (wink, wink) and Prussia in general, came to the throne. He pursued for peace, and thus gave Prussia a big break. The Treaty of Hubertusburg of 1763 made very little changes on the Continent. Prussia had only grown in power, not weakened. William Pitt’s Strategy for Winning North America The survival of Prussia was less impressive to the rest of Europe than the victories of GB. The architect of these victories was William Pitt the Elder. Pitt was a person of colossal ego and an administrative genius who had grown up in a commercial family. He pumped tons of money to Frederick. He did this to distract the French into a continental war. While both countries were providing money, the French also had to fight on the Continent while GB didn’t. Pitt later boasted of having won America on the plains of Germany. North America was the center of Pitt’s real concern. He wanted all of NA east of the Mississippi. He got it, too. He sent 40,000 troops to fight the French (a huge number back then). He also had the undivided cooperation of the American colonies, who wanted that extra land every bit as much as he did. The French were unwilling and unable to direct similar resources to the colonial conflict. Their military administration was corrupt, their command divided, and its troops not adequately prepared. Quebec City, that impregnable fortress, fell in Sept 1759. Pitt also wanted the major islands of the French West Indies. He sent major naval power and took them over. Income from the sale of captured sugar helped finance the British war effort. British naval intercepts of French merchant ships ended the French slave trade. Between 1755 and 1760, the value of French colonial trade dropped 80%. In India, the British forces under Robert Clive defeated the French under Dupleix at the Battle of Plassey (each man, who worked for the company and not his country, led an army of Indians to battle. The British only won because they had taught their Indian soldiers to cover their gunpowder from the rain). This victory opened the way for the eventual conquest of India by the British East India Company. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 The Treaty of Paris gave Britain less than what it really had won. This was because George III had quarreled with Pitt and dismissed him. This started the revolving door of prime ministers of GB, which continued until Lord North in 1770. Britain got the land it wanted in NA but returned several Caribbean islands and several Indian trading posts/cities to the French. Overall, Prussia had finally secured Silesia against the Hapsburgs. Mohit Agrawal (4.9) The HRE was now an empty shell. Hapsburg powers depended more than ever on a teetering alliance with the Magyars of Hungary. France was no longer a colonial power (but still a Continental power). The Spanish empire was still largely intact, for now, but the Spanish were quickly losing their trading monopoly with their colonies. The British East India Company continued to get political power as local governments crumbled. Now the British had to sit down and actually govern all this new land. GB was now a world power, not just a European one. The French and the Spanish started to haltingly embark on political and administrative reform due to their losses in war. Every European power had to do financial reform to pay their debts and prepare for the next conflict. The American Revolution and Europe The war erupted from problems of revenue collection common to all major powers after Seven Year’s War It also continued conflict between France and GB French support of Americans deepened existing financial/administrative difficulties of French monarchy Resistance to the Imperial Search for Revenue After Treaty of Paris of 1763, British gov faced 2 problems. One was the sheer cost of empire, which British felt they couldn’t carry alone. National debt /domestic taxation had risen considerably. B/c American colonies had been chief beneficiaries of the conflict, British felt it was rational for colonies to bear part of cost of their protection/administration Why Britain Was Right and America Was Wrong America was a country full of brutes who refused to pay any reasonable level of taxation. The British, in an attempt to pay down some of the debt caused by decades of fighting and to administer its new colonies, tried to impose quite reasonable taxes on luxury items, such as paper and stamps. The American colonists didn't seem to have a problem with these taxes, until 1764 when Britain started to get serious about collecting some of them. All of a sudden, a massive media campaign was undertaken to decry “taxation without representation.” The Commonwealthmen movement in Britain, which by comparison was more obscure in England at that time than the Libertarian party is in the United States today, became the standard of American expectations of republicanism and liberty. Others sources of friction also show that some Americans exaggerated the democratic ideal in order to make more profit. Many wealthy merchants resented the British trade restrictions and thought that if they resisted enough, like with the Stamp Act, Parliament would retreat and give them free trade. Also, while the Americans decried their lack of representation, they refused to send representatives to London “due to the distance.” This was a great circular way of getting out of paying taxes—complain about no representation, and then say that representation was not feasible in the first place. Moreover, there was no proper “representation” in Britain at this time, as massive cities had fewer votes than empty farm fields. In essence, the wealthy in America formulated the resistance to Britain in an attempt to get lower taxes. To this end, they sent petitions, boycotted products, engaged in smuggling, and protested violently. Clearly from the British perspective, the colonists could be considered spoiled brats. Mohit Agrawal (5.9) Two was that Britain now had to organize this vast expanse of territory, including all the land from mouth of Saint Lawrence river to Mississippi river, w/ its French settles and, its Native American possessors British drive for revenue began in 1764 w/ Sugar Act under prime minister George Grenville. It was actually a lower tax than the original, but it was much more enforced. The tax was now low enough that smuggling wasn’t cheaper. Thus, the merchants who rebelled against this tax actually wanted normal Americans to pay more for sugar, so that they got more profit. Pretty self-centered, huh. Smugglers violating law were tried in admiralty courts (royal courts) w/o juries. The Stamp Act passed the next year which put a tax on legal documents, newspapers, etc. British considered taxes legal b/c decision to collect them approved by Parliament. They regarded the taxes as just b/c money was to be spent in the colonies. Americans said that only the colonies could tax themselves b/c they weren’t represented in Parliament. Also, the expenditure in colonies of revenue levied by Parliament didn’t reassure colonists who feared that if colonial govs were financed from the outside, the colonists would lose control over them. In Oct 1765, the Stamp Act Congress met and drew up a list of protests and sent it to the king. This congress was important b/c it set a precedent of federalism and of the colonists banding together against Britain. A group called the Sons of Liberty roused disorder in the colonies, mostly MA. The colonists also announced a general boycott. In 1766, Parliament backed down, but passed the Declaratory Act which said that it did have the power to tax the colonies. The Stamp Act crisis set the patter for the next ten years. Parliament would approve new taxes, which Americans would then resist by reasoned argument, economic pressure, and violence. Britain would then eventually back down. Each time, tempers on both sides became more frayed and positions more irreconcilable. The Crisis and Independence In 1767, Charles Townshend had Parliament pass a new series of revenue (Townshend) acts. These were “different” because they were an indirect tax paid by the British monopoly companies, and not the colonists directly. The colonists against resisted. GB sent over customs officials to enforce the law, and then sent troops to protect those officials. Those troops (who had been badgered by out-of-work dock workers and were facing a growing riot) then fired into the crowd and killed five men in March 1770. This was the great Boston Massacre, which the colonialists used as propaganda. Parliament then repealed all the taxes except the one on tea. In 1773, Parliament allowed the British East India Company to sell tea directly to the colonies. This was because the company was in a financial crisis (because Americans had stopped buying its products) and needed more revenues. This lowered the price of tea, and even with the tax, made it cheaper than smuggled tea. In some cities, the colonists refused to permit the unloading of the tea; in Boston, a raiding Mohit Agrawal (6.9) party of Indians threw tea overboard in the great Boston Tea Party. This infuriated prime minister Lord North. In 1774, Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts. This closed Boston’s port until the tea was repaid, reorganized the gov of MA, allowed quartering, and let royal officials be given trials back home in England. Parliament also passed the Quebec Act, which have the entire Ohio River Valley (that Virginia and Pennsylvania so wanted) to the much more royalist government in Quebec. During the 1770s, the colonists had started committees of correspondence to help spread news about Britain and its atrocities up and down the seaboard. In Sept 1774 these committees organized the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. note: an often ignored cause of the revolution was that George III’s was attempting to regain royal power both at home and in the colonies. So the colonists were right when the feared losing control of their own colonial governments The congress simply asked Parliament to grant the colonies more autonomy. Of course, they said no. By Apr 1775, the Battles of Lexington and Concord had been fought. Important battle 1: Bunker’s (Breed’s) Hill, June 1775. The Americans actually held their ground and fought the British. They retreated in an orderly fashion. They lost many fewer men than the British (the total casualties at this one battle was more than the rest of the war put together) and made the British realize that this might not be such a cakewalk. The Second Continental Congress met in May 1775. It still formally pursued for peace, but it began preparing for the war (ie by establishing the Continental Army). Thomas Paine’s Common Sense galvanized American opinion against Britain that winter. Important document 1: the Declaration of Independence was singed on July 4, 1776. Important battle 2: Saratoga (1777). The three pronged British plan completely failed. Only one prong reached Saratoga, and Gen. Benedict Arnold won. This was the battle that made the French support us. Important document 2: the Articles of Confederation. The Articles were designed to only be in effect during emergencies (like the war). The states thought that they could go back to acting independently once the war was over. It obviously didn’t work for mostly economic reasons—the states began to compete and too many farmers were going into bankruptcy— and also because no state wanted to pay its fair share of the debt. The federal gov had no power of taxation and had to ask the states to donate troops to the army. Important battle 3: Yorktown. Lafayette led the American forces onto the York Peninsula (they only followed him because they wanted French gold). Gen. Cornwallis thought that he could escape by sea if the Americans would actually come (he wasn’t expecting very many). However, the French navy blockaded the river and kept the British navy occupied. After weeks of siege, Cornwallis finally surrendered. The French made him surrender to the Americans, which infuriated him and all future Britons. The war could have dragged on except that Parliament in Britain wanted to stop the financial bleeding. Anyway, GB made more money on trade with America after independence than it ever did before independence. Important document 3: the Constitution. It was written in 1787 and ratified in 1788. It provides for a much stronger federal government, but still gives much power to the states and the people. It didn’t deal with slavery because the Northerners thought that slavery would die out naturally over the next 20 years (it didn’t because of the cotton gin). The constitution was only ratified after the Federalists promised that the Bill of Rights would be added on later. American Political Ideas Mohit Agrawal (7.9) The American colonists looked to the English Revolution of 1688 as having established many of their own fundamental political liberties. The colonists claimed that the measures of parliament between 1763 and 1776 attacked those liberties. Ironically, the colonists employed a theory that had developed to justify an aristocratic rebellion to support their own popular revolution (though, if you think about it, the American Revolution was basically an aristocratic revolution as well). The Whig political ideals as espoused by John Locke were at the core of the American policies. The Commonwealthmen group, considered radical republicans in Britain, gained a following in the Americas. Britons, when they compared themselves to other Europeans, thought that they were pretty well off and ignored the radicals. However, the radicals’ message of corruption, nonrepresentation, and excessive patronage rang a bell with the Americans. Americans thought that most taxes were wasted as corruption. They also considered standing armies in times of piece a form of tyranny. Events in Great Britain George III believed that a few powerful Whig families had controlled his royal predecessors. George III also believed that he could choose his own ministers without Parliamentary input and that he should have more direct power in Parliament. By appointing the earl of Bute after William Pitt the Elder, George snubbed the great Whig families. George finally settled on Lord North in 1770, someone who could finally gain enough support in Parliament and stayed prime minister until 1782. During this period of active monarchial rule, the Whigs cried out that George was becoming a tyrant. They were just complaining that they were no longer in favor, of course. However, their actions gave fuel to Americans who actually did think that George was a tyrant. The Challenge of John Wilkes In 1763 began the affair of John Wilkes. He was a radical London newspaper publisher and a member of Parliament. In his paper, he strongly criticized Bute’s handling of the peace negotiations of the 7 years war. He was arrested for libel and treason under a “general arrest warrant.” The courts let him go because he was a member of Parliament and because the general arrest warrants were deemed unconstitutional. He was expelled from Parliament, however, and quickly fled the country. He had much popular support, though. In 1768, Wilkes returned to Britain and won an election for Parliament. However, the House of Commons refused to seat him. He was re-elected three more times, and each time he was not seated (not sworn in). After the fourth election, the House simply ignored the results and seated the government-supported candidate. Large protests broke out and several aristocrats, who wanted to hurt George III, started to support Wilkes. Wilkes won the election for mayor of London, and was finally seated in the House in 1774. The events in Britain confirmed the American colonists’ fears about a monarchical and parliamentary conspiracy against liberty. Mohit Agrawal (8.9) The Wilkes affair displayed the arbitrary power of the monarch, the corruption of the House of Commons, and the contempt of both for popular elections. Movement for Parliamentary Reform American criticism started to have some effect back home. British subjects at home, who also did not have “representation” per se, adopted American arguments. Both the colonial leaders and Wilkes appealed over the head of legally constituted political authorities to popular opinion. They were protesting the power of the self-selected aristocrats. Those in power clearly understood these developments and sought to stop them. The American colonists also demonstrated how the people could take power and organize congresses and conventions to govern. The legitimacy of these congresses and conventions lay not in existing law but the consent of the governed. This was a new approach to government. The Yorkshire Association Movement By the end of the 1770s, like in America today, people resented the mismanagement of the war and blamed prime minister Lord North. In 1778, Christopher Wyvil organized the Yorkshire Association Movement. Property owners of Yorkshire met in a mass meeting to demand rather moderate changes in the corrupt system of parliamentary elections. They organized corresponding societies elsewhere and started to suggest reforms for all parts of government. The Association Movement was thus a popular attempt to establish an extralegal institution to reform the government. The movement collapsed in the early 1780s due to internal disagreements. In 1780, the House of Commons passed a resolution calling for lessening the power of the crown. In 1782, Parliament reformed parts of the patronage system, limited how much the monarch could give out. Lord North was dispatched in 1783 and was eventually replaced by William Pitt the Younger in the same year. George threw much patronage support behind Pitt. Pitt was able to secure the election of a very favorable House. In 1785, at the height of his popularity and power, Pitt was still unable to get parliamentary reform passed. By the mid-1780’s, George had succeeded in making the monarchy more relevant to England. However, his later mental illness would severely weaken the institution’s power. Broader Impact of the American Revolution The Americans demonstrated government without kings or hereditary nobility (think about this, this was very revolutionary at the time. No nobility? At all?). The government’s powers were clearly delineated in certain documents, and it clearly ruled by the consent of the governed. The Americans would embrace democratic ideals—even if the franchise (vote) remained limited. They would assert the equality of white male citizens not only before the law, but in ordinary social relations. Mohit Agrawal (9.9) They asserted the necessity of liberty for all citizens to improve their social standing and economic lot by engaging in free commercial activity. They did not, however, free their slaves, empower women, or address the problems with the Native Americans. In all these respects, overall, the American Revolution was a genuinely radical movement, whose influence would widen as Americans moved across the continent and as other peoples began to question traditional modes of European government.