Buddhism is a very diverse religion and teachers will find this helpful

advertisement

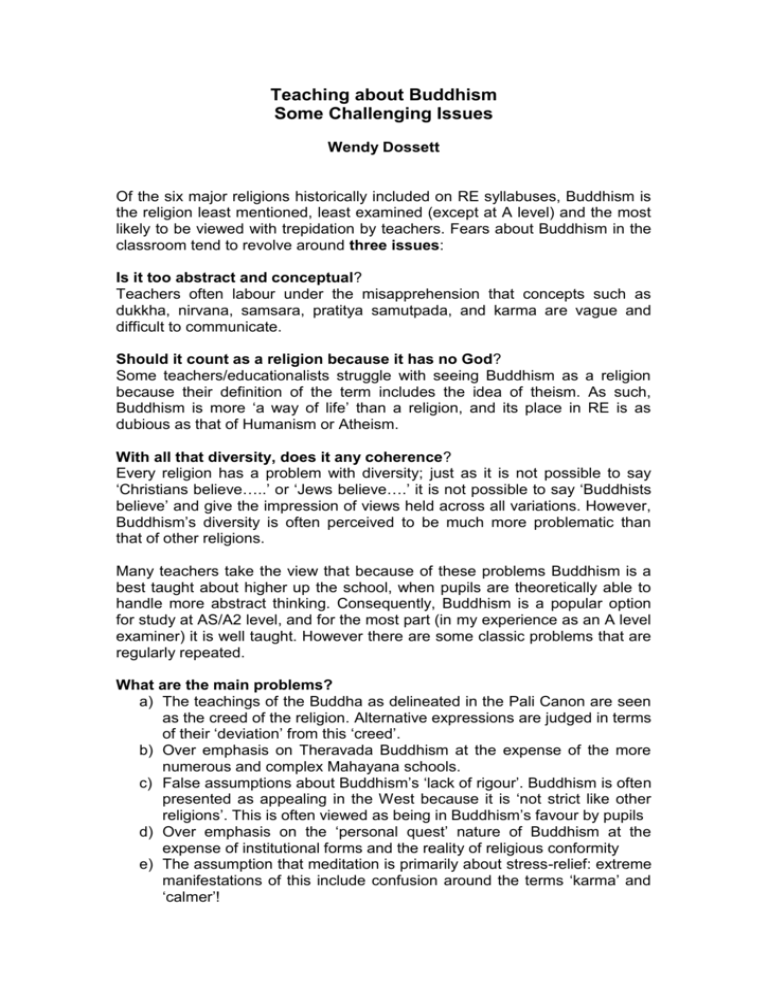

Teaching about Buddhism Some Challenging Issues Wendy Dossett Of the six major religions historically included on RE syllabuses, Buddhism is the religion least mentioned, least examined (except at A level) and the most likely to be viewed with trepidation by teachers. Fears about Buddhism in the classroom tend to revolve around three issues: Is it too abstract and conceptual? Teachers often labour under the misapprehension that concepts such as dukkha, nirvana, samsara, pratitya samutpada, and karma are vague and difficult to communicate. Should it count as a religion because it has no God? Some teachers/educationalists struggle with seeing Buddhism as a religion because their definition of the term includes the idea of theism. As such, Buddhism is more ‘a way of life’ than a religion, and its place in RE is as dubious as that of Humanism or Atheism. With all that diversity, does it any coherence? Every religion has a problem with diversity; just as it is not possible to say ‘Christians believe…..’ or ‘Jews believe….’ it is not possible to say ‘Buddhists believe’ and give the impression of views held across all variations. However, Buddhism’s diversity is often perceived to be much more problematic than that of other religions. Many teachers take the view that because of these problems Buddhism is a best taught about higher up the school, when pupils are theoretically able to handle more abstract thinking. Consequently, Buddhism is a popular option for study at AS/A2 level, and for the most part (in my experience as an A level examiner) it is well taught. However there are some classic problems that are regularly repeated. What are the main problems? a) The teachings of the Buddha as delineated in the Pali Canon are seen as the creed of the religion. Alternative expressions are judged in terms of their ‘deviation’ from this ‘creed’. b) Over emphasis on Theravada Buddhism at the expense of the more numerous and complex Mahayana schools. c) False assumptions about Buddhism’s ‘lack of rigour’. Buddhism is often presented as appealing in the West because it is ‘not strict like other religions’. This is often viewed as being in Buddhism’s favour by pupils d) Over emphasis on the ‘personal quest’ nature of Buddhism at the expense of institutional forms and the reality of religious conformity e) The assumption that meditation is primarily about stress-relief: extreme manifestations of this include confusion around the terms ‘karma’ and ‘calmer’! f) The assumption that religion should ‘fit in’ with life, rather than challenge it. Buddhism is often perceived uncritically by pupils to accommodate easily to secular values and lifestyles. g) The problem of isolated items of belief or practice being seen as normative, resulting in others being deemed deviant (e.g. Japanese Buddhists being understood as deviant because they don’t celebrate Wesak). Selecting material: how do I choose? A number of these problems are, in part, simply the inevitable result of selecting material to be covered in a short time. Not all festivals in the Buddhist world can be explored; a selection has to be made. Wesak is a good example of a festival because it explicates many aspects of Buddhism covered in standard syllabuses. Japanese Obon is a bit more problematic because it involves the spirits of the dead, and therefore some understanding of the nature of the person in the light of the Buddhist doctrine of no-self (anatta) must be reached before Obon can be understood. Thus if there is a choice, Wesak is the obvious one. Which sort of Buddhism? However, a number of these problems arise from a more general problem in Buddhist studies, which harks back to Buddhism’s first inception in the West. There is a bias towards Theravada Buddhism in many presentations of Buddhism at every level of education because Theravada was the first form of Buddhism to be encountered and written about. Early British pioneers, such as TW Rhys David, Ananda Metteya and others encountered Theravada Buddhism as a result of British colonial links with Asian countries in which Theravada dominated. This accident of history, coupled with the Western notion that historically earlier forms of the religion are somehow more ‘authentic’ than historically later ‘explications’, lead to an inappropriately strong emphasis on Theravada as the normative version of Buddhism. This has numerous consequences for the study of Buddhism at any Key Stage, because the predominant popular (media-produced) image of Buddhism is that of the Theravada monk. (At the time of writing the protests of the monks in Myanmar are headline news, further reinforcing this particular stereotype in the popular imagination). The vast majority of Buddhists worldwide are not monks or nuns. The impression that monastic Buddhism is ‘proper’ Buddhism leads to value judgements implicit in accounts of the religion. It also leads to the view that the texts and practices appropriate to a monastic context are widely used in Buddhism and constitute the corpus of the Buddhist ‘creed’. This leads to problems when it is discovered that this is far from the case. The kind of problems indicated above crop up in a range of ‘areas’ within the study of Buddhism. Only a selection of some of these ‘areas’ for discussion is possible in a short article like this, but the areas listed below are amongst some of the most significant. The centrality of the life of the Buddha Historicity and the life of the Buddha Buddhism and God The teaching of ‘no-self’ Teaching about meditation Teaching about Buddhism in the West The Centrality of the Life of the Buddha Understandably, at any Key Stage, most presentations of Buddhism begin with the life of the Buddha. The story provides an engaging focus, the pupil is able to identify with the story of a single human being, and the stories in the life have been used to explicate Buddhist teachings within the Buddhist religion throughout the generations, so why not use them in a secular educational context as well? Furthermore, resources on the life of the Buddha are plentiful (see for example the Keanu Reeves film The Little Buddha – whilst the story of the Californian family and their encounters with Buddhist Lamas may be of some limited use, the dramatisation of the life of Siddhartha Gautama is captivating, and provides helpful illustrations of the some of the traditional/scriptural accounts of his life. See also the Key Stage Three pack on Buddhism produced by the educational wing of the FWBO – The Clear Vision Trust). Two Major Problems There are two major problems with giving so much emphasis to this story. The first is that not all Buddhists value the traditional story of the life of the Buddha. The life of the Buddha is central in Theravada Buddhism and some forms of Buddhism which have derived from Theravada, such as the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order. It is not central in many forms of Mahayana Buddhism, and some forms of Mahayana Buddhism do not mention the life of Shakyamuni (a Sanskrit title for Siddhartha Gautama) at all. For these schools of Buddhism the focus is very much on other things, such as the possibility for all of enlightenment in this life and body, a particular scripture (for example the Lotus Sutra), a particular figure in Buddhist history (for example, Dogen, Nichiren or Shinran), a particular enlightened being, such as Avalokitesvara, Amida, the Dalai Lama or a ‘Dharma-protector’, or a particular practice or set of practices, such as the koan or zazen. When pupils have been taught that the life of the historical Buddha is the foundation stone of Buddhism, problems are encountered when it is clear that different traditions value the story differently. The second major problem with the centrality of the Buddha in presentations of Buddhism is that it suggests that the Buddha plays a role equivalent in Buddhism to that of founder figures in other religions (eg the role of Jesus in Christianity, Muhammad in Islam, Moses in Judaism and so on). This is a problem with teaching about religions in general. Whilst it’s not a mistake to point out that there are over-arching themes across religions, it is a mistake to ignore the differences inherent in different instances of the theme. Thus, the Buddha is like Jesus in that he provides us with the first expression of a set of teachings; he is male; a single figure, somewhat shrouded in history but fairly likely to have existed; likely to have had an impact on those around him; likely to have been a critic of the religious status quo; but also profoundly unlike Jesus in that there is no requirement within the religion which grew as a consequence of his life to ‘believe in him’ or to consider that his life was a sacrifice for the atonement of the sins of humanity. An important question to consider is ‘If there could be no Christianity without Jesus, could there be Buddhism without the Buddha?’ Whilst it might correctly be said that they are both ‘founders’, they are very different in terms of the role that they play within their respective religions. It is important that any presentation of Buddhism takes into account the likely presuppositions of the audience. In a post-Christian context, it is likely that an assumption will be made that the Buddha is ‘the Jesus’ of Buddhism. This requires correcting before a start is made, and demonstrating that the historical Buddha is one amongst a number of enlightened beings in Buddhism more generally is one way of doing this. For the higher key stages, the ‘Three Bodies of the Buddha’ theory, and the Lotus Sutra’s emphasis on the notion of ‘skilful means’ (upaya) are both helpful notions for contextualising the story of the Buddha. Historicity and the life of the Buddha The traditional life of the Buddha is a hagiography. This means it tells us more about how the Buddha was valued and understood in the community that wrote down the stories about him (centuries later) than it does about historical facts about the person himself or events in his life. Any presentation of the life of the Buddha should seek to explain what particular features of the story might mean in the context in which they were written down. For instance there are many striking features in the traditional account of the Buddha’s conception and birth. His conception is said to have taken the form of a dream his mother had of a white elephant entering her side. He is said to have been born not in the usual way, but from his mother’s side as she lent against a tree. He is said to have taken seven steps and to have spoken as soon as he was born. In order to understand any of these stories, the information that sex and childbirth are considered ritually defiling in the Indian context, so the stories of conception and the manner of his birth are told to indicate notions of ‘purity’. White elephants are auspicious. Walking and speaking at birth are signs of great spiritual advancement in the context of the Indian belief in rebirth. Just as in the previous section, problems arise if the Buddha is assumed to play the same role in Buddhism as Jesus does in Christianity. Whilst it may make sense to say that striking features of Jesus’s life such as walking on water, the healing miracles and the Resurrection are believed by most Christians to be historically true (and this importantly so because it demonstrates God’s historical relationship with human beings), the striking features of the Buddha’s life do not need to be seen in the same historical terms. This is not to say that Buddhists do not believe them (many do), but that questions about historical truth or fact do not have the same critical status as they do in Christianity. Pupils need to be enabled to handle myth and allegory in order to get beyond the dualistic notion that a story is either true or false and to be able to appreciate meaning. Buddhism and God The claim that Buddhism is a religion is often rejected on the basis that Buddhists do not believe in God. Here the issue depends on which definition of religion is in operation. In our post-Christian context the uncriticised assumption that religion is about belief in at least an invisible realm or power, if not a deity, tends to underlie many discussions and definitions of religion. Ninian Smart’s phenomenological ‘seven dimensions of religion’ provide a framework which can help get beyond this simplistic and unhelpful idea. According to this framework, we have no problem identifying Buddhism as a religion. It has without doubt all of the seven dimensions.1 Those definitions of religion which exclude Buddhism usually have either an explicit or an implicit ‘theological’ agenda within them. But what do Buddhists believe about God? In the traditional Buddhist worldview there are many realms of existence, amongst which the realm of the gods is just one. Gods are seen, not in Western Classical Theism terms of omnipotent, omniscient and benevolent, but simply as more evolved beings, who suffer less than humans or some other beings, but who are still nevertheless trapped in the wheel of samsara which turns on greed hatred and delusion. So, it is not really appropriate to worship or emulate the gods. They are just ‘there’. In relation to ‘God’ in the western sense, Buddhists usually make no comment. They argue that it is not necessary to posit ‘God’ in order to explain the universe, and that belief in God does not help the Buddhist overcome greed hatred and delusion. They point out that many believers in God, convinced of their rightness, simply add to the sum of suffering by being sectarian or judgemental, and becoming blindly attached to a mere ‘idea’ themselves. They also make the same points about people who cling passionately to the belief that there is no God. So most Buddhists are not atheists in the sense of having coming down on the negative side of the question ‘Is there a God?’ Most Buddhists simply do not see the question as a useful one to ask. They are much more concerned with rooting out greed hatred and delusion in their daily lives than with speculating about questions to do with the origins of the universe, or life after death, of whether there is an omnipotent omniscient God looking down on us. Pupils who operate with theistic definitions of religion may struggle with Buddhism. It is worthwhile going back to basics and looking first at what we think ‘a religion’ is, and not automatically giving authority to definitions which are theistic. Very often representations of religion given in RE/RS operate on the assumption of ‘religion is basically to do with belief in god or gods, and then you’ve got Buddhism which is a bit different’, as if Buddhism is let in on some ‘charity clause’. This is problematic because it assumes theism is normative. It is far better to get the underlying issue (the definition of religion) right first. The Seven Dimensions are ‘experiential’, ‘social’ , ‘narrative’, ‘doctrinal’, ‘ethical’, ‘ritual’ and ‘material’ 1 Teaching about no-self In a similar way, often religions are presented in relation to the idea of a soul. ‘Most religions believe that there is some part of the human, a soul or spirit, which survives death either to be reborn or to go to an afterlife. And then there’s Buddhism which is a bit different because it doesn’t belief in the soul, or even the self.’ This is also an unhelpful presentation, because the natural response of most pupils who give it a minute’s thought is ‘that’s rubbish, of course I’ve got a self’. Part of the problem arises from the translation of the term in Pali anatta and in Sanskrit anatman. The Sanskrit term atman means soul or self, and in a Hindu context indicates the immortal unchanging essence of the person which transmigrates to different realms of rebirth. A strong feature of the Buddha’s teaching was the critique of this idea that was very much current amongst the religious teachers of his time. However, at no point does the Buddha say there is no such thing as the individual. All he says is that if you break down a person into its component parts, you don’t find this ‘essence’ that is immortal and unchanging. Traditionally in Buddhism the person breaks down into five aspects – the skandhas or aggregates and each is subject to flux and change and is contingent on other aspects. Therefore none of the skandhas can qualify as the ‘soul’ or atman. However this does not mean that although in flux, the skandhas are an illusion or not present. Individuals are very much present. The only problem arises when individuals begin to think they are immortal, and to treat other people and the environment as if there were immortal too. Given this, it is often suggested that a more accurate and less misleading translation of anatman would be ‘no-fixed-self’ or ‘no-permanentself’. If there is no soul, how can Buddhists believe in rebirth? Having understood the concept of what makes up a human being according to the traditional Buddhist account of the skandhas, pupils often then struggle with the fact that Buddhists believe in rebirth. If there is no soul, what is it that is reborn? In order to understand this it is helpful to be reminded that whilst Buddhists are not eternalists (in the Buddhist worldview nothing goes on for ever, the notion of the everlasting life of the soul for example makes no sense) they are also not materialists (they do not see the person as being made of the body only), and they are not nihilists (they do not believe that the death of the body is ‘the end’). Thus, whilst the skandhas might be continually in flux, they may project forward into other lives beyond the death of this body. Pupils find the illustrations traditionally used by Buddhist teachers to explain this helpful. Milk and yoghurt are two different substances; however milk provides the conditions for yoghurt to come about. In the same way, one life provides the conditions for the next one to come about. They are different, yet related, one being the cause of the other. It is our Western (Cartesian) way of thinking which assumes that if something goes from one life to the next, it must be an immortal soul. How can I teach about meditation Edward Conze the great Oxford buddhologist described meditation as ‘the heartbeat of Buddhism.’ When meditation is taught about in British classrooms, it is often done so in a way that divorces it from its Buddhist context. Meditation becomes about ‘stilling’ and is about ‘emptying the mind’ and about ‘stress-relief.’ This is profoundly problematic in the context of studying Buddhism. Stilling and stress-relief are important by-products of meditation but not the purpose of it. ‘Emptying’ the mind is not normally considered a worthy goal either. Training the mind to focus with mindful awareness is one of the main purposes, and this is very different from ‘emptying’ it. In the classroom difficult decisions have to be made about whether to provide the direct experience of meditation for pupils. This raises all sorts of questions about the difference between belonging to a religion and practicing within it, to studying it in an academic context. Many teachers understandably prefer to keep that distinction clear. Some teachers are willing to allow their pupils to be exposed to a visitor (either to the classroom, or in the context of a trip out), of course protecting the rights of pupils to opt-out for whatever reason, who will lead pupils in meditation. In the UK for example it is quite easy to get hold of an order member of the Western Buddhist Order, who would lead pupils in a simple mindfulness of breathing meditation, or a Theravada practitioner who would teach them the Metta Bhavana. Other teachers venture into this themselves and have experiential sessions on meditation in the context of their teaching about Buddhism. The main problem with this practice is the trivialising of meditation. Teachers would be less keen to worship Allah, or offer the Eucharist in the classroom; and whilst it is not exactly comparing like with like, it might be considered just as inadvisable. School teachers are not (usually) trained meditation adepts, and classrooms are not meditation rooms. Pupils will assume that whatever ‘experience’ they may or may not have had in the classroom is the experience that Buddhists are seeking, and make completely inappropriate judgements as a consequence. This practice may also account for the widespread view that Buddhism is a religion of stressrelief. It is clear from public examination papers that many A Level pupils do not have a robust sense of the purposes of meditation. This is likely to be because they have been taught through an experiential approach that has distorted the subject. Teaching about Buddhism in the West One of the challenging issues in teaching about Buddhism in the West is the pervasive assumption that Buddhism is appealing because it conforms to secular standards and lifestyles. It is easy to see where this notion comes from; Buddhism doesn’t believe in God; the by-products of a Buddhist lifestyle are similar to those sought in modern health and environment-conscious lifestyles; there is an emphasis within Buddhism on ‘testing the teachings in the crucible of ones own experience’ rather than on accepting the authority of senior figures, institutions or scriptures; and Buddhism is often seen as being compatible with the scientific worldview. However, the claim that in contrast to religions like Christianity and Islam which are all about rules stopping you following what you want to do, Buddhism ‘fits in’ with however a modern Westerner wants to live life, is deeply problematic. In the first place it does not take account of the diversity of Buddhism in the West. Whilst on the one hand there is the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order who do indeed explicitly put great importance on how individuals wish to live their lives, and are keen that such decisions should not be seen as barriers to the practice of Buddhism, on the other hand there is the English Sangha Trust who support a British monastic community who keep all of the 228 precepts in the Patimokkha. And of course there is a vast array of groups and movements in between, reflecting the enormous range of Buddhism’s global diversity, and hugely varying levels of commitment to precepts and lifestyles. Even the idea, however, that going for refuge in the three jewels could be seen as ‘fitting in with modern life’ is problematic. Refuges for modern secular people are vast and varied, they may be a combination of consumerism and individualism or family values or new age beliefs or celebrity and television. The Buddhist refuges are very clear and distinctive. To go for refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha is profound statement of difference and distinctiveness from prevailing worldviews. The claim also rests on some dubious assumptions about other religions too. Teaching about Buddhism would benefit from being characterised by the following considerations. That an understanding of the religious language of myth and allegory is helpful for understanding the meaning of the life of the Buddha and of other enlightened beings That Buddhism is diverse and there is no group which can be said to be ‘core’ or ‘essential’ Buddhism That too much focus on the historical Buddha leads to a distorted picture of Buddhism as a whole That Buddhism’s main doctrines are communicable, and the resources of the tradition itself can be used to achieve this That teaching about meditation needs to be set in the doctrinal context of Buddhism That Buddhism should not be considered the exception to ‘the rule’ that religions are about belief in God (rather ‘the rule’ should be dropped) That beliefs and practices are diverse and cannot be understood in isolation from their social and cultural context