From Left Liberal to FLOW Libertarian

advertisement

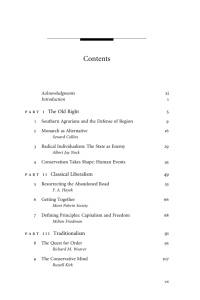

From Left Liberal to FLOW Libertarian An Annotated Bibliography Michael Strong CEO and Chief Visionary Officer, FLOW, Inc. A Gestalt Shift QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. This bibliography is a tool for those who are interested in experiencing a gestalt shift. The familiar image above allows one to experience a visual gestalt shift: One can learn to shift from an old woman looking down into her fur coat to a young woman looking away and back again. Likewise, those who are interested in understanding different ways of looking at the political and economic structures of our society might be interested in learning how to make a gestalt shift from left-liberalism to libertarianism and back again. Until and unless one has understood both interpretations of the world, one doesn’t fully understand the various ways in which evidence may be interpreted in different frameworks. Unfortunately, it takes some work, some reading, some thought, and some conversation, to lead to understand a different politico-economic gestalt. For those who are interested in experiencing such a gestalt shift, this bibliography may serve as a guide. 3/8/16 1 My Gestalt Shift I am a left liberal who became a libertarian strictly as a consequence of new intellectual understandings. That is, I have exactly the same ideals, morals, goals, and values as I did when I was a left liberal. But I moved away from left liberalism and towards libertarianism because I came to believe that libertarian approaches would be more effective at achieving my ideals than would left liberal approaches. Given that my goals and ideals continue to be those of a left liberal, there are many of my positions and priorities that differ from those of some mainstream libertarians. Thus my position may be better described as “left libertarian” or “communitarian libertarian” or “FLOW libertarian,” in recognition of the non-profit that I head devoted to promoting these ideas. For a general perspective on FLOW’s origins and rationale, see John Mackey, “Winning the Battle for Freedom and Prosperity” http://www.flowidealism.org/john.html There are several other FLOW-related articles by John at that URL. For a more personal statement of my perspective, see Michael Strong, “Taking the Left out of Liberal” http://www.flowidealism.org/michael.html My FLOW related articles, including most of those listed below, are available at that URL. This is an annotated bibliography for the intellectually serious left-liberal who may be engaging libertarian ideas seriously for the first time. It’s organization follows the main themes that were key to my own conversion from left-liberal to libertarian: 1. Public choice theory 2. Creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship 3. Property rights solutions to tragedy of the commons problems 4. Economic freedom leads to peace and prosperity for all 5. Liberating entrepreneurs in health, education, insurance, community formation, and law 6. The poor in the developed world 7. Prediction as an intellectual standard 8. Academic fallibility 9. History 10. 20th Century Libertarian Classics I welcome questions, comments, and recommendations for additional readings. I have not included here resources on entrepreneurship, positive entrepreneurship, Conscious Capitalism, and other topics that focus on the increasing capacity for 3/8/16 2 entrepreneurs and business to engage in doing good directly. For a brief orientation to the issues in this debate, and how John Mackey explicitly disagrees with Milton Friedman on this topic, see John Mackey, Milton Friedman, T. J. Rodgers debate at Reason Magazine, “Rethinking the Social Responsibility of Business,” reprinted here at John’s Whole Foods Market blog, http://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/blogs/jm/archives/2005/09/rethinking_the.html Before providing materials relevant to the shift, a few orienting thoughts to help leftliberals begin to consider such a shift: 1. Scandinavia regulates business less, and has more economic freedoms, than the entire developing world. Poverty is caused by a lack of economic freedom, and the probability of civil war decreases dramatically as societies become more prosperous, so in order to eliminate poverty and reduce the probability of violent conflict our first priority should be to get the developing world at least as free market as Scandinavia. 2. Peter Barnes’ Capitalism 3.0, endorsed by leading progressives, promotes property rights solutions to tragedy of the commons problems. In essence, this is a “free market environmentalism” solution that has now become accepted by leading progressives and environmentalists as a way to solve environmental problems. 3. Improving education is the most urgent means of helping the U.S. poor while also moving American culture beyond materialism, consumerism, and addictive behaviors. In order to improve education, we need to allow innovative educators the autonomy to innovate. We need to liberate educational entrepreneurs to solve our most urgent problems, and that cannot be done through the existing educational bureaucracy. At present, it is easier to innovate in the gambling and pornography industries than it is in the education industry. One on one it is not difficult to get informed left-liberals to accept each point above once they see the data and understand key concepts. Once they develop a firm moral commitment to each of the foregoing, completely honorable goals, if they are willing to learn how to make the Gestalt shift into a libertarian understanding, most will never shift back completely to their old left-liberal paradigm. I hope that many will join me in creating a left libertarian idealism that achieves their ideals more effectively and more quickly than 20th century leftist thought ever could. Let me know if a link doesn’t work or if you can’t find something there. I may be contacted at Michael@flowidealism.org. 1. Public choice theory 3/8/16 3 The left is often animated by the various harms and crimes committed by large corporations. Leftists experience a tremendous sense of outrage at the fact that under capitalism not only do bad people get away with doing bad things, they often become rich and powerful by means of doing so. Worse yet, under capitalism often highly decent, hard-working human beings are harmed by these evil people, and are impoverished, or may be actively harmed by the actions of evil, rich capitalists. Coming from an honorable and authentic moral sensibility, Leftists then devote themselves to fighting capitalism; the past two centuries have seen a diverse array of Leftist initiatives designed to defeat these injustices, including Marxism, democratic socialism, and the welfare state. I remain interested in eliminating these injustices, but am now more wary of certain kinds of government action which, I believe, tends to make the situation worse rather than better. The implicit assumption on which Leftist beliefs are founded is that the initiatives designed by the Left to counteract the harms done by capitalism do more good than harm. In the case of Marxism, almost everyone now agrees that the “cure,” Marxism, was worse than the “disease,” capitalism. But “public choice theory” provides a powerful way of understanding government that shows why the “cure” of government action can be worse than the “disease” of capitalism. For a simple rule of thumb, I would suggest that government actions that improve the rules of the game can improve capitalism, but government actions that involve government trying to control the system directly (rather than re-structuring the rules) is almost always harmful. Often I find myself in agreement with solidly Democratic economists, who would never describe themselves as libertarian, because they understand the distinction between re-structuring the rules rather than trying to control the system directly. Section V of Michael Strong and John Mackey, Liberating the Entrepreneurial Spirit for Good sketches some of the rule-based policy moves that I regard as most effective at eliminating these injustices. For an excellent bi-partisan introduction to public choice theory, see Jonathan Rauch, Government’s End: Why Washington Stopped Working Endorsed by Democrats David Broder, Daniel Patrik Moynihan, and Bill Bradley, it describes how special interests have made progress in government nearly impossible. Rauch does an excellent job of introducing the fundamental public choice theme of the arithmetic of focus: special interests have an incentive to devote extraordinary resources to fine details of legislation and regulation, whereas the rest of us, even the most motivated citizens among us, can’t possibly understand even a tiny fraction of government’s activities. 3/8/16 4 For a more insidious view of the numerous ways in which special interests are working to control government, see Charlotte Twight, Dependent on D.C.: The Rise of Federal Control over the Lives of Ordinary Americans Twight’s book makes clear that the means through which special interests insinuate control to protect their own turf is limited only by the bounds of human creativity. She documents numerous details concerning how special rules, laws, and regulations are passed that benefit special interests. David Malin Roodman, The Natural Wealth of Nations: Harnessing the Market for the Environment Published by The Worldwatch Institute, shows how cutting environmentally harmful subsidies could result in a $2,000 tax refund to every family in America. Although Roodman’s book is mainstream environmentalism rather than public choice theory, as one reads about these dozens of subsidies from a public choice perspective one can’t help but note that most of the subsidies were advocated by the left-liberal establishment decades ago and, as public choice theory predicts, the have quietly metastastised into enormous corporate subsidies through which government pays companies to destroy the environment. The Green Scissors Campaign http://www.greenscissors.org/ is a joint lobbying effort between tax cutters and environmentalists to try to eliminate environmentally-damaging subsidies. For a more theoretical, but still readable, approach to public choice theory, see James Buchanan, Public Choice: Politics without Romance Buchanan won a Nobel Prize for creating the field of public choice theory, according to which voters, politicians, bureaucrats, and judges all act in accordance with the incentives they face based on the limited information at hand. Buchanan’s original work in public choice theory was done with Gordon Tullock, who also has a readable volume on public choice theory, Gordon Tullock, Gordon Brady, and Arthur Seldon, Government Failure: A Primer in Public Choice I’ve not yet read Bryan Caplan, The Myth of the Rational Voter 3/8/16 5 But based on an earlier article by Caplan on which the book is based, it sounds like an excellent, accessible addition to the public choice literature. Much is made of the ways in which it disagrees with mainstream public choice literature, but I see Caplan’s thesis as more of a complement to mainstream public choice. Caplan is focusing on the extent to which our moral intuitions evolved to prefer statist policy “solutions,” without understanding how damaging they are, a theme that Hayek developed and that evolutionary psychology is confirming. The great insight of public choice theory is that just as markets sometimes fail to perform in accordance with the theoretical ideal of markets, due to systematic, identifiable shortcomings, so too do democratic governments sometimes fail to perform in accordance with the theoretical ideal of democracy. Once one starts to examine the actual incentives faced by government actors along with the information available to them, it becomes apparent that the systematic flaws of democratic government are pervasive and non-trivial. ` This does not mean that we should give up altogether on democracy, but it does mean that we need to develop more realistic expectations regarding the types of problems that it is likely to be able to solve. Most people who study public choice theory become more libertarian than they were before simply because they come to realize that many outrages that one sees in government are not simply due to this or that politician or bureaucrat, but rather chronic problems that are likely to take place in any large-scale democratic government. And scale matters – part of the challenge of democratic decision-making is information. Small, local democratic government is apt to work better than does large, pluralistic government because the informational demands expand exponentially. As a consequence of this scale issue, I am far more in favor of government action at the local level than I am at the national level. Finally, it is worth being aware of F. A. Hayek’s most famous work, F.A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom For me personally it is one of my least favorite pieces by Hayek. It is both dated and polemical. That said, as long as one understands that he was writing about an interpretation of socialism in which the government attempted to control all prices and production, it stands as an effective analysis for why such a system of comprehensive control will always tend to result in the worst people rising to the top. A good antidote to those Marxists who want to claim “We didn’t know that the bad people would lead communist regimes.” Hayek explained quite clearly, in 1944, why we should expect that socialism, understood as total state control of the economy, should consistently result in the bad people gaining power in such regimes. While I’ve not read it, I understand that James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed 3/8/16 6 Is, in effect, a left-liberal safe version of Hayek and public choice theory. Although he overtly disavows Hayek, by all accounts Scott is merely Hayek lite. Academic bigotry prevents him from acknowledging his legitimate predecessors from the free market movement, even as intellectual honesty compels him to admit their conclusions were valid. A short history of 20th century economic and political thought might be summarized as: 1. Market Failure! Markets don’t work as well as the classical economists thought and therefore we must control them (1900 – 1960) 2. Government Failure! Governments don’t work as well as democratic theorists thought, and therefore we can’t depend on them to do the right thing either (1960 – 2000) Regardless of what one thinks regarding the relative role of markets and government, it is important to understand the public choice theory, the theory that explains why governments systematically, predictably put special interests before the public interest. 2. Creativity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship This is far and away a more exciting and uplifting topic. The most important case for freedom of action is that it is essential for allowing a creative, innovative, entrepreneurial society. Millions of individuals, all free to create new enterprises, will in time always outperform a cumbersome, contentious political process. The political process can only make a few decisions from time to time, and the range of decision options is always limited by the real constraints faced by the political agents involved. The entire point of “free enterprise” is that anyone can start something up and see if it works. The entire rise of the late 20th century IT industry in the U.S. is a tremendous validation of the innovative powers of the free enterprise system. Remarkably, and sadly, relatively little has been written on this. Economists (and other social scientists) almost all ignore innovation because ex ante it doesn’t exist – all empirical studies ipso facto ignore prospective innovation. This is a banal thought that nonetheless stands as a profound indictment of empirical social science except for those very rare cases in which the social scientists explicitly take the possibility of innovation into account (please send me examples of such social science when you find them – they are very rare and I want to create a museum of such exotic species). A great place to start is Virginia Postrel, The Future and Its Enemies Endorsed by good Democratic stalwarts and cool Silicon Valley gurus Steward Brand and Esther Dyson. Postrel shows that both the Left and the Right are hostile to innovation, and the importance of innovators to support an open system that will allow 3/8/16 7 innovation to continue to improve our lives going into the future. Postrel’s book stands as a sort of pop version of Hayek. Earlier I referenced our formal statement of FLOW, which includes much emphasis on entrepreneurial innovation for the good, Michael Strong and John Mackey, Liberating the Entrepreneurial Spirit for Good As of Nov. 2007 it is mostly complete and mostly posted on our website. We are finishing up sections of this each month, so check back if a section is missing. We expect to publish it in book form in 2008. For a good interview with Paul Romer, the leading contemporary economist dealing with innovation, see Ronald Bailey, “Post-Scarcity Prophet” http://www.reason.com/news/show/28243.html It is noteworthy that Romer’s introduction of innovation into formal economics really only took place in the 1990s – this shows how neglected the topic was in economics prior to that. Peter Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Addresses the issue of innovation and entrepreneurship from a management perspective; as such he provides an excellent overview of the possibilities and obstacles to launching new innovations. The core text on this theme, virtually a sacred text for me, is F. A. Hayek, “The Creative Powers of a Free Civilization,” Available as the second chapter of Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty or I will send you a text file copy if you are interested. Hayek shows that the case for freedom of action is structurally identical to J.S. Mill’s case for freedom of speech. Just as freedom of speech is crucial if you believe that there is still more to learn and discover in the realm of thought, so too is Hayek’s article crucial for understanding that freedom of action is crucial if you believe there is still more to learn and discover in the realm of action. My essay Michael Strong, “Perceptual Salience and the Creative Powers of a Free Civilization” Connects Hayek’s epistemology with his political theory; somewhat heavy going, but it may entice those to learn more about his theory of the mind, which has since been used 3/8/16 8 by brain researchers (his theory is similar to the better known Hebb connectionist model on which contemporary neural networks are, in part, based). Most Americans would probably claim that they support the idea of innovation; but until one has grasped the full Hayekian scheme, one does not generally understand the extent to which innovation is profoundly dependent on an entire ecosystem of institutions and the price signals that are generated by those institutions. For more on the Hayekian theory of information and knowledge, see F.A. Hayek, “The Use of Knowledge in Society” F.A. Hayek, “Economics and Knowledge” F.A. Hayek, “Competition as a Discovery Process” It is interesting that Hayek was regarded as “right-wing” and “reactionary” throughout much of the 20th century, despite the fact that in his 1960 classic, “The Constitution of Liberty,” he conceded the entire welfare state and wrote an epilogue, worth reading, titled F.A. Hayek, “Why I Am Not a Conservative” More than anything, Hayek believed in the freedom to innovate and he had a deep understanding of the institutions needed to support innovation. For an application of Hayekian creativity to education, see Michael Strong, “The Creation of Conscious Culture through Educational Innovation” For an interesting independent interpretation of free enterprise as a fantastic system for innovation, see Michael Rothschild, Bionomics A few sections are slightly dated, but his examples are so well done that it is well worth reading nonetheless. George Gilder, Wealth and Poverty Is even more dated, and I hesitate to include it only because some sections may no longer be worth reading, but it was an important historical book in that it made the case for the innovative power of the market economy in 1981, before the tech revolution really hit its stride, and his book was a significant influence on the Reagan and Thatcher political revolutions. It is worth noting that in 1968 Gailbraith claimed the age of entrepreneurship was over. I highly recommend Frederick Turner, “Make Everybody Rich” 3/8/16 9 http://www.independent.org/publications/tir/article.asp?issueID=16&articleID=124 Why don’t governments enact policies that would make everyone rich? Universal prosperity would not make everyone happier, but it would greatly advance the causes of world peace, environmental protection, education, health care, women’s rights, employment, sustainable growth, racial harmony, political liberty, scientific discovery, spiritual renewal and the arts. A slightly tongue-in-cheek essay that points out that upper income people tend to place a higher value on the environment, education, culture and the arts, etc. and can afford to devote resources to these problems, and that therefore the single most effective solution to most problems is to “Make Everybody Rich.” He points out that if 20th century U.S. rates of economic growth continue into the 21st century, the average American household income for a family of four in 2100 will be $320,000. Despite his ironic tone, Turner is correct that we should “Make Everybody Rich” and that economic growth is the way to do it. Ernesto Sirolli, Ripples from the Zambezi: Passion, Entrepreneurship, and the Rebirth of Local Economies Is an inspiring statement by a follower of E.F. Schumacher on how nurturing spontaneous passion towards entrepreneurship is the real solution to helping disadvantaged communities, not government programs. Sirolli describes his successes in helping people in depressed communities create successful businesses that turn the communities around. There are various books that attempt to apply complexity theory and chaos theory to society that are unwittingly quasi-Hayekian but because they are not aware of it they are not worth mentioning here. But at some point someone needs to write a book showing the extent to which Hayek’s insights on innovation foreshadowed some of the work being done at, for instance, the Santa Fe Institute of Complexity. Paul Ormerod, Butterfly Economics: A New General Theory of Social and Economic Behavior Looks to complexity theory and chaos theory to sketch a “new general theory.” While there is much interesting material here, to some extent it amounts to a new way to articulate Hayekian insights. Hayek’s epistemology is in many respects similar to Karl Popper, Objective Knowledge, an Evolutionary Approach And Donald T. Campbell’s work on evolutionary epistemology. Indeed, the cumulative insights of Hayek, Popper, and Campbell have barely begun to be elaborated. Academia 3/8/16 10 will be a far richer place the more deeply the concepts of evolutionary epistemology are integrated into the humanities and social sciences in the 21st century. For many on the left, my emphasis on creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship seems like a no-brainer – of course these things should be supported. But creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship are crucially dependent on freedom. One of the reasons I became a libertarian is the realization that I care more about making peoples’ lives better than I cared about “social justice” or tracking down bad people who made money being bad. While I remain interested in reputation systems to ensure that bad people less frequently get away with getting rich by being bad, I have decided that it is far more important to focus on making lives better than to focus on prosecuting the bad. I believe with increased freedom we can create peace, prosperity, happiness, and well-being for all, rapidly, in an environmentally sustainable world, and this goal is far more valuable than is the goal of fighting bad guys who happen to get rich through pandering and deceit. 3. Property Rights Solutions to Tragedy of the Commons Problems Environmental issues now motivate many of those who are hostile to markets. It is little known that free market economists developed a robust analysis for how to create environmental sustainability many decades ago. Ever since Garrett Hardin analyzed the concept of “Tragedy of the Commons” in the late 60s, economists have seen that a lack of property rights was the problem and that well-defined property rights would be the solution. Hardin pointed out that in a situation in which resources were unowned, such as a fishery or a free pasture, each fisherman or rancher would have an incentive to overfish or over-graze, thereby destroying “the commons.” Hardin and other economists have pointed out that the solution to such a problem is to make sure all resources are owned, because commons, or “common pool resources,” will generally be abused. The usual way in which we ensure that the resources are owned is to grant property rights to individual fishermen or ranchers that designate some specific ownership share of what was formerly the commons so that they have an incentive to preserve the long-term value of the resources that they own. For diverse applications of this notion, see Terry Anderson, Free Market Environmentalism Most progressives and environmentalists will be put off, even horrified, by some of Anderson’s solutions, however, so his book should be read more for curiosity’s sake rather than to feel secure about the ability of free market environmentalism to solve problems. A far more appealing approach to progressives and environmentalists (which will disgust conservatives and libertarians) is Peter Barnes, Capitalism 3.0 3/8/16 11 Barnes is very much a progressive environmentalist writing a book for progressive environmentalists. His concept of “environmental trusts” allows for a property rights solution to tragedy of the commons problems that avoids outright privatization (that which repels most progressives regarding property rights solutions to tragedy of the commons problems.) A great short essay by Barnes, that contains the most important elements of his thought is available from the E.F. Schumacher Society: http://www.schumachersociety.org/publications/barnes_03.html For a general overview that explains why market-based solutions are more effective, see Michael Strong, “Sustainability in a Bright Green Future” A little noticed fact is that, over the past forty years as the environmental movement has matured, many leading environmentalists and environmental groups have become increasingly drawn to market mechanisms to solve environmental problems simply because they are more effective. For example, The Environmental Defense Fund advocates pollution trading rights Worldwatch endorses a green tax shift The Rocky Mountain Institute endorses a green tax shift Jeffery Smith, a Green Party founder, now focuses on land taxes, as do many local Green Party chapters Patrick Moore, a Greenpeace founder, now supports various market mechanisms When one talks to these individuals or reads their stories, one hears a story of how deeper study of environmental policy resulted in an understanding that market mechanisms are simply more effective at reducing environmental harms. Although not specifically about environmental issues, Stephen Rhoads, The Economist’s View of the World: Governments, Markets, and Public Policy Provides a great summary of the economist’s perspective from a “New Democratic” (Gary Hart, Bill Clinton) perspective, including both the positives and negatives of the economist’s perspective. He shows why, by the 1980s, policy wonk Democrats were looking to market solutions to solve environmental problems as well as to solve problems in other areas. 3/8/16 12 It is also worth pointing to the literature showing the various ways in which environmental harms have often been exaggerated in the past. For instance, Bjorn Lomborg, The Skeptical Environmentalist Has abundant data showing that things are not as bad as alarmists often portray them as being. Scientific American did a hatchet job on Lomborg, and I think it is incumbent upon the fair reader to read both their attacks and his defenses. Although there are clearly places where Lomborg made mistakes, on balance I think he looks even better after their attacks than before. Jack Hollander, The Real Environmental Crisis: Why Poverty, Not Affluence, is the Environment’s Number One Enemy Is a very compelling, sane book showing the various ways in which the environment typically improves as countries become wealthier. John McCarthy, “Sustainability of Human Progress,” http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/progress/sustainability-faq.html is a slightly dated website with diverse original material on why McCarthy is an optimist with respect to human progress. Lomborg, Hollander, and McCarthy all make arguments that are extremely unpopular among environmentalists, but they should not therefore be completely ignored. They may not be correct in every detail, but given the saturation we receive from mainstream media sources regarding environmental catastrophe, they put things in some much needed perspective. Gregg Easterbrook, The Progress Paradox Is more of a mainstream left-liberal safe summary of much of the same data that have caused Lomborg, Hollander, and McCarthy to be roasted alive – Easterbrook gets away with saying many of the same things simply because he aggressively demonstrates his left-liberal bonafides in various ways. For a more courageous left-liberal who is open concerning his heretical beliefs, see Steward Brand, “Four Environmental Heresies” He predicts (again, to his credit, whether he is right or wrong) that in the next decade environmentalists will shift ground with respect to their beliefs regarding population growth (no longer really an issue), urbanization (good), nuclear power (good), and genetically modified foods (good). Finally, for the truly brave at heart, check out 3/8/16 13 Paul Driessen, Eco-Terror: Green Power, Black Death Driessen pulls no punches in summarizing the various ways in which the environmental movement has caused death and exacerbated poverty in the developing world. The environmental movement’s opposition to the use of DDT for fighting malaria plays prominently in this, but before dismissing this movement note that among the supporters of a renewed role for DDT in malarial control are Ralph Nader, Desmond Tutu, Lancet, and the World Health Organization. Environmentalists are outraged by the claims of Driessen and others that they are responsible for millions of malarial deaths, but there is very solid evidence that tens of thousands died unnecessarily, a strong case that the number extends into the hundreds of thousands, and fair likelihood that it could well have been millions. A humorous but still hard-hitting look at the dark side of environmentalism is the DVD Mine Your Own Business Showing that environmentalist opposition to mining operations in poor nations is often resented by locals who want jobs. 4. Economic Freedom Leads to Peace and Prosperity A good place to start here is with Michael Strong and Theodore Malloch, “Economic Freedom as Development Goal” And Michael Strong and Theodore Malloch, “Betting on a Brighter Future: Millenium Villages or Free Cities?” Both available from me. For deeper background, see the most recent Fraser Institute Economic Freedom of the World Report, especially the essays contained in the 2005 report (by Erik Gartzke on peace and economic freedom) and the 2006 report (by William Easterly on economic freedom and poverty alleviation): http://www.freetheworld.com/ This and the footnotes to the Strong and Malloch paper will lead to a rich, well documented literature on the subject. Johan Norberg, In Defense of Global Capitalism 3/8/16 14 Is, to a considerable extent, a reader-friendly summary of many of the findings in the Economic Freedom of the World Reports. Everyone should read William Easterly, White Man’s Burden About the failure of foreign aid and the need for “searchers” rather than “planners” as well as Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else De Soto should win a Nobel Peace Prize soon. Bill Clinton describes his organization in Peru as “the most effective poverty alleviation organization in the world,” and I think Clinton is correct. One should also read the book by De Soto’s friend Mohammad Yunus, Banker to the Poor The famous story of Yunus’ founding of Grameen Bank. And to watch PBS, Free to Choose PBS, Commanding Heights PBS deserves credit for broadcasting both of these gems. More academic, but still crucial reading, is Douglass North, Understanding the Process of Economic Change North is a Nobel laureate economic historian whose work re-focused economists on the role of key institutions: property rights and rule of law, but in the context of a sophisticated analysis of the interplay between cognition, culture, law, and economic actors. Gurcharan Das, India Unbound Is a beautiful, sad account of how Nehruvian socialism perpetuated poverty with the best of intentions, and how free market reforms in the 1990s created dynamism and wealth in India. Das, who became head of P&G India, has deep sympathies for the spiritual side of India, and wants to preserve both Indian spirituality and free market dynamism going forward. I haven’t read it in twenty years, but key to my own conversion was 3/8/16 15 Peter Berger, The Capitalist Revolution: Fifty Propositions about Prosperity, Equality, and Liberty See also Michael Strong, “Forget the World Bank, Try Wal-Mart” On Wal-Mart as the world’s single most effective anti-poverty organization. Although this article brought me a lot of hate mail from Wal-Mart haters, not one of them disputed any of the data I produced in making my case. On the peace side of the equation, see, Michael Strong, “A Million Paths to Peace” And Michael Strong, “Understanding the Power of Economic Freedom to Create Peace” There is a statistical social science literature on this and a historical classical liberal literature on this for interested parties. Erik Gartzke is a leading social science scholar doing work in this area; Gartke’s work is great if you like to read regression analyses. For more of an international relations perspective, from a world-class scholar, see Michael Mandelbaum, The Ideas That Conquered the World For a moderately politically incorrect (simply due to his frank endorsement of Anglosphere institutions and culture) but quite fascinating idiosyncratic study of the role of market economies in the 21st century, see James C. Bennett, The Anglosphere Challenge: Why the English-Speaking Nations Will Lead the Way in the 21st Century Bennett may or may not be correct, but he summarizes much interesting literature from diverse sources that is relevant to these issues but not available from standard disciplinary works in economics or political science. For those interested in the story of Africa’s extreme poverty, it is well worth reading Martin Meredith, The Fate of Africa For an intelligent account of western failures towards Africa, George Ayittey, Africa Unchained 3/8/16 16 Ayittey also includes an aggressive defense of traditional African institutions, including African markets and tribal chiefs, as providing a more appropriate foundation for African development, rooted in indigenous African notions of economic freedom, than the alien ideologies imposed on Africa by socialist elites upon independence. Ayittey is a westerntrained Ghanan economist who intelligently integrates western economic understanding with understanding of, and love for, indigenous African institutions. Finally, I’ll recommend two more short articles by me that address related issues not dealt with elsewhere in this list: Michael Strong, “Milton Friedman, A Modern Galileo” Michael Strong, “Developing a New Standard of Social Justice” 5. Liberating entrepreneurs in health, education, insurance, community formation, and law This is an area that has not received adequate attention, though if one digs into the libertarian literature one can find fascinating gems in this area. A good place to start is David Beito, Peter Gordon, and Aledander Tabarrok, The Voluntary City: Choice, Community, and Civil Society Former California Governor Jerry Brown, currently Mayor of Oakland, endorses it saying “The exciting and pioneering book, The Voluntary City, sketches out a provocative vision for communities based on civil cooperation and entrepreneurship. Drawing upon a fascinating history of city innovations, the book shows why the de-bureaucratization of urban life is crucial to fostering thriving markets, vibrant neighborhoods and educational excellence. A book worth reading.” For more on voluntary aid systems see David Beito, From Mutual Aid to the Welfare State And Richard Cornuelle, Reclaiming the American Dream Cornuelle’s work was endorsed by Saul Alinsky, the famous Leftist community organizer from the 1960s. See Howard Husock, “New Philanthropists Talk Left, Act Right” 3/8/16 17 On the similarities between the new social entrepreneurship movement and earlier civil society principles long advocated by libertarians and conservatives and described by Cornuelle and Beito (above). It is also worth reading the complaint by organic farmer Joel Salatin, “Everything I Want to Do is Illegal” To get a sense of how ordinary people wanting to do good projects are thwarted by government at every turn. For a very mainstream Harvard Business Review article on the concept of disruptive innovation for social change, see Clayton Christensen, Heiner Baumann, Rudy Ruggles, and Thomas Sadtler, “Disruptive Innovation for Social Change” I wrote Clayton after I saw the article and pointed out to him he should have been more aggressive about the need to “legalize entrepreneurs of happiness and well-being” and he completely agreed with both my perspective and language and said he wished he had thought of it. With respect to education to I am in some respects a pioneer in writing about the importance of educational freedom for educational entrepreneurship. Many free market authors have, of course, written about the possibility of educational entrepreneurship, but I am one of the very few who has actually started innovative schools. That said, John Taylor Gatto, “Seven Lesson School Teacher” http://www.newciv.org/whole/schoolteacher.txt is a crucial prerequisite to understanding the real issues in education. Gatto fans will want to get John Taylor Gatto, Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling Which is excellent in perspective, but somewhat repetitive. See David Skinner, “Libertarian Liberals: When the Left was Right,” http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0MJG/is_4_5/ai_n15950344 3/8/16 18 On the 1960s history of anti-establishment educational radicalism, starting with Ivan Illich but going well beyond Illich. Many of my articles on education address the issue of innovation in education. See Michael Strong, Ten School Designs Michael Strong, A Tale of Two Charter Schools Michael Strong, The Dyson Vacuum Cleaner and Educational Innovation Michael Strong, Why We Don’t Have a Silicon Valley of Education Michael Strong, Legalizing Markets in Happiness and Well-Being, Part I Michael Strong, Legalizing Markets in Happiness and Well-Being, Part II Michael Strong, Why Do We Have Better Product Information on Sports Cars than We Do on Schools? Michael Strong, Renewing the Promise of Montessori Education Michael Strong, How to Avoid Wasting $60 Billion in K-12 Educational Philanthropy Already referenced, but important along these lines as well, is Michael Strong, “The Creation of Conscious Culture Through Educational Innovation” Finally, a very important work that takes off flying in a direction that is profoundly interesting to me is Spencer MacCullum, “The Enterprise of Community” MacCullum finished an important book by Van Notten on how to develop modern commercial law from traditional Somali tribal law; see Michael Van Notten, The Law of the Somalis For a fascinating anthropological approach that connects the tribal with the modern. Van Notten married a Somali woman and lived for many years within her clan; he understands both worlds from the inside out. Bruce Benson, The Enterprise of Law Starts with an analysis of tribal law and then shows how a free market legal system more closely approximates many of the original benefits of tribal law. He also has a great deal of valuable material on more dreadful public choice shenanigans in our existing legal system. 6. The Poor in the Developed World When I began investigating free market economics, I was very focused on economic injustice and inequality. Once I realized that free enterprise is the fundamental engine behind economic growth, and thus the alleviation of poverty and misery, I became less 3/8/16 19 concerned about “economic injustice” because I realized poverty alleviation was more important than the distribution of income. As I realized that government action often had unintended consequences, I became even less enthusiastic about using government to address economic inequality. That said, I had a profound commitment to increasing social mobility, which is one of the reasons I became professionally involved in K-12 education. If one believes that the poor ought to have the same opportunities as the rich, then one ought to do something about it, and I spent fifteen years doing something about it (until the system kicked me out a second time despite having proven that I could educate poor kids far more effectively than existing public schools). Thus for me, the single most important means of helping the poor in the developed world is to legalize access to good education, through charter schools, virtual schools, school vouchers, education tax credits, and ultimately through the separation of school and state. The government education monopoly is a cruel enforcer of class hierarchies that will someday be regarded with the same horror as 19th century child factory labor is regarded today. Beyond legalizing markets in happiness and well-being, I also support legalizing affordable housing. See Michael Strong, “Getting Serious About Helping the U.S. Poor” To address the many myths about a “declining working class standard of living,” see W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm, Myths of Rich and Poor Beyond the power of innovation to provide endlessly better goods for all at endlessly lower prices, I am open to various forms of a “Citizen’s Dividend” to help the poor in the developed world. For instance, Charles Murray, In Our Hands: A Plan to Replace the Welfare State Promotes the idea of giving every American citizen $10,000 each year – and also eliminating the welfare state as we know it. Peter Barnes, Capitalism 3.0 Mentioned above, promotes giving each citizen a dividend based on their share of resources sold by publicly held environmental trusts. There are also various Georgist approaches to helping the poor. Henry George was a 19th century economist and social reformer whose ideas were widely discussed for several decades, until the conventional Left vs. Right political battles drowned out his more sensible perspectives. Georgists promote the idea of taxing land, but not the development on the land, as well as not taxing income, savings, or investment. It turns out that this has profound implications. Simply to address the issue of helping the developed world poor, 3/8/16 20 it is worth noting that Hong Kong and Singapore both have significant government control of land and government subsidized housing markets – and yet they are ranked as the two most free market nations on earth and are the two most successful stories of nations in terms of economic growth over the past forty years. One could be a Georgist libertarian and endorse a significant Citizen’s Dividend based on land taxes that would ensure a comfortable base salary for the poor, and yet still promote as free market an economy as one pleased. For one practical sketch that moves in this direction, see Jeffery Smith, “Geonomics: The Citizen’s Dividend Liberates Everyone” Smith was a founder of the Green Party who became more of a Georgist the more deeply he studied the incentive structure of society and realized that the real issues were all driven at that level. The conflict between libertarians and those concerned with the poor has been an unfortunate red herring – it is all too rarely acknowledged that Milton Friedman is the father of the Earned Income Tax Credit, widely acknowledged to be one of the most effective poverty alleviation programs in the past forty years. Milton Friedman, Gary Becker, and F.A. Hayek are among the libertarian thought leaders who have written supportively of Georgist redistribution schemes. It is also worth noting that both Oxfam, the venerable progressive NGO, and Joseph Stiglitz, probably the most left-wing Nobel prize winning economist, both support the unilateral elimination of trade barriers in the developed world. Thus complaints that “free trade” will take away job opportunities for the poor in the developed world are recognized by both as a lesser moral issue than the fact that trade barriers take away job opportunities from the truly poor in the developing world. 7. Prediction as an Intellectual Standard There are many on the left who would like to believe that the rise of free market economics in the past forty years is due simply to funding from right-wing think tanks. The fact is, free market economics has won largely because it is more effective at predicting the outcomes of policies than were various flavors of alternative economics. But rather than argue this, as economists and other social scientists did throughout the 20th century, at this point I’m more interested in encouraging people to put their money where their mouths are and commit to predictions regarding the future outcomes of various policies they advocate. See, for instance, Michael Strong, “Put Your Money Where Your Theory Is” 3/8/16 21 For a short application of this concept to academia. For the original source of this line of thought, and a great article, see Robin Hanson, “Could Gambling Save Science?” I think Hanson deserves, and may get, a Nobel prize for this article someday. For an application of this standard to education, see Michael Strong, “How to Avoid Wasting $60 Billion in K-12 Educational Philanthropy” In short, if anything here seems “ideological” my retort is “Let’s try to find an empirical outcome and try to predict what will happen.” Such a process actually improves dialogue, because it forces people to become very specific about what particular propositions they believe will have what particular empirical consequences. Often initial disagreements are considerably smaller once one focuses in on specific empirical outcomes. And, I contest, once critics of capitalism begin to think more carefully regarding the actual predicted outcomes of various policy proposals, and are forced to put their reputations and/or their income on the line, they become far more realistic about both markets and government. For another approach, influenced by Hanson, see Stewart Brand, Long Bets http://www.longbets.org/ Brand, whom I regard as a hero, is a sensible man of integrity who realizes that bets keep all of us more honest and more sane. 8. Academic Fallibility Much of the above addressed various aspects of academic fallibility. But it is worth adding Paul Hollander, “Judgments and Misjudgments” the closing chapter of Lee Edwards, The Collapse of Communism About mistaken judgments by academics and intellectuals regarding communism. Although most of us over forty dimly remember intellectuals praising communism, there is something revoltingly powerful reading a collection of the insanities mumbled by many of our leading thinkers. As Hollander mordantly points out, the intellectuals’ moral enthusiasm for Stalin’s Russia was highest at about the same time that Stalin was killing some 30 million, enthusiasm for Mao’s China was highest at about the same time Mao was killing 60 million, and passion for third-world communist “wars of liberation” peaked at about the same time that Pol Pot was killing more than a quarter of his country- 3/8/16 22 man. To juxtapose the intellectual’s lavish praise for these leaders and their regimes with the actual consequences that were taking place in each nation at the time is stunning. Those who wish to go more deeply into this might read one of Hollander’s books or Joshua Muravchik, Heaven on Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism Muravchik was a red diaper baby, so his account of the egregious failures of judgment has a poignant quality to it. He tries to be gentle on his parents while simultaneously being brutally honest. He was chairman of the Young People’s Socialist League from 1968 to 1973. A conservative classic, that should now become a mainstream classic, is Whittaker Chambers, Witness Chambers’ account of his role as a Soviet spy and his accusation of Alger Hiss as a Soviet spy is amazing. And now we know that it is largely true despite the most vicious attacks made on Chambers by the elite liberal establishment in defense of one of their own. “The Lives of Others” is a splendid German film that deservedly won many awards that documents the horrors of living under the Stasi, the East Gerrman secret police. Just as there is a rich literature on WWII and the Nazis, in coming years we’ll see an increasingly rich literature documenting the horrors of communism. Jung Chang, Wild Swans, is a beautiful novel documenting three generations of Chinese women, starting with her grandmother who was given to a general as a concubine when she was fifteen, with bound feet. But much of the story is that of her mother, who became a communist to fight injustices such as this but finally discovered that communism under Mao was even worse than pre-communist China. The story ends with Jung escaping to the West as a student. She subsequently co-wrote Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, Mao: The Untold Story That documents his crimes more thoroughly than has ever been done before. It is noteworthy that Howard Zinn still praises Mao; to a Jung Chang, this is as sane and humane as praising Hitler and still somehow remaining respectable. 9. History For me, the relevant histories are the ones that emphasize the role of creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship. For instance, Daniel Boorstin, The Creators Daniel Boorstin, The Discoverers 3/8/16 23 Are not in the least political, but they remind us of the amazing sequence of events through which our world has been expanded by means of human discovery and ingenuity. More focused on specifically classical liberal virtues is Arthur Herman, How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe’s Poorest Nation Created Our World and Everything In It The title is marketing hype forced on him by his American publisher; in Britain the same book was released simply as “The Scottish Enlightenment.” That said, it is a marvelous history of the Scottish Enlightenment and the truly extraordinary memes it released. This book inspired me to include the Scottish Enlightenment alongside Periclean Athens and Renaissance Italy as the three most creative episodes in Western civilization. Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern: World Society 1815-1830 Provides an extraordinary look at an extraordinary period, the real birth of the industrial revolution and the modern era. Yes, the steam engine and industrial society was born at the end of the eighteenth century, but Johnson examines the period during which technology really transformed society. Industrial society was still small and marginal in 1815 – by 1830 the transition to modernity was moving full speed ahead. A simply amazing period of creativity and invention. Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches Shows the key role that tinkerers played in created the industrial revolution. Often there is the false notion that scientific discovery made all the difference. While science was important in the second industrial revolution, in the late 19th century with electricity and chemistry, the first industrial revolution was largely the work of individual, uneducated tinkerers. William McNeill, The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community A slightly dated classic, this is still an excellent overview of the social and political dynamics that resulted in the dynamism of western civilization. F.A. Hayek, Capitalism and the Historians Is not history per se, but it includes essays by various economic historians in which they point out the ways in which historians created a misleading view of capitalism. The most important example, of course, is that historians perpetuated the belief that under unfettered capitalism “the rich got richer and the poor got poorer.” In fact, economic historians have shown that under laissez-faire capitalism in Britain from 1840-1860 the working class standard of living steadily improved. It turns out there are dozens and 3/8/16 24 dozens of myths that the historians have perpetuated, sometimes through ignorance and sometimes through animosity towards capitalism. Thomas DiLorenzo, How Capitalism Saved America: The Untold History of Our Country, From the Pilgrims to the Present Is an overly simplistic libertarian revisionist history. That said, DiLorenzo’s book is a convenient “one stop shop” that corrects many of the mistaken views of U.S. history written by mainstream historians who are ignorant of economics. Wherever DiLorenzo seems overly simplistic, take his account with a grain of salt, but then go back to his sources and discover the rich literature by more thorough scholars that back up most of his statements, most of the time, remarkably well, albeit with greater nuance. We need a more sophisticated telling of the story told by DiLorenzo. Frederick Turner, Shakespeare’s Twenty-First Century Economics: The Morality of Love and Money Is literary criticism rather than history per se, but Turner does an excellent job of showing the vibrant connection between the dynamic openness of Shakespeare’s world view and the dynamic openness of Elizabethan England, an openness that provided the foundation for the first wealthy nation on earth in the late 18th century due, in part, to the positive attitude towards commerce developing among the British. Most cultures around the world have been instinctively hostile to commerce; British exceptionalism in this respect is an under-developed theme in understanding “the rise of the west.” 10. 20th Century Libertarian Classics Most libertarians will be disappointed that I put these at the end rather than at the beginning. For me, one of my motivations for creating FLOW and doing much of my writing is because most existing libertarian literature is not very accessible to the average left-liberal reader. Libertarians already live within their own ethos, already take for granted too many elements that are only visible on this side of the Gestalt shift. I certainly learn from many libertarian classics and am grateful to these authors for their work, and at the same time some of them do have a right-wing crankiness that I find unnecessary, unappealing, and distracting. The violent political conflicts of the 20th century distorted everyone’s judgment. Now it is time for us to digest the best of both sides and get on with it. Mary Ruwart, Healing Our World Is a great summary of libertarian thought appealing to left liberal sentiments. She provides a wonderful introduction to the overall libertarian perspective to the openminded left liberal. That said, there remain traces of traditional libertarian enthusiasms that I don’t share – guns, for instance – that may unnecessarily alienate left-liberals. That said, this is the single best introduction to libertarianism for left-liberals. 3/8/16 25 David Boaz, Libertarianism: A Primer David Boaz, The Libertarian Reader: Classic and Contemporary Writings from Lao-tse to Milton Friedman Boaz, head of the Cato Institute, provides what might be regarded as the “establishment view” of libertarianism. Much valuable material is available in his anthology, starting with Lao-tse as the first libertarian. Charles Murray, What It Means to Be a Libertarian Is an excellent personal statement. Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom Milton and Rose Friedman, Free to Choose Are both well worth reading. Capitalism and Freedom, written in 1960, is more academic and more dated. Free to Choose, written to go along with the PBS series by that name, is a brisk summary for the public that came out in 1980 and is thus less dated. David Friedman, The Machinery of Freedom Is an excellent presentation of anarcho-capitalism by Milton’s son David. Anarchocapitalists believe that the best form of government is strictly voluntary and contractual – each of us would have the freedom to contract with the legal services and defense services provider of our choice. A fascinating, if somewhat speculative approach, Friedman cites medieval Iceland as a place where as system like this actually existed. F. A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty More accessible chapters of which were mentioned above (“The Creative Powers of a Free Civilization” and “Why I Am Not a Conservative”), is a long, hard grind, heavy and academic, but it does provide an excellent summary of classical liberal principles for those who are ready to go deep into this world-view. Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged Are both a bit over-the-top for my tastes, and yet when one realizes that most of the world took communism seriously as a superior moral ideal when she wrote these – and that she had actually lived in communist Russia before escaping – then one can read her pro-capitalist purple prose more sympathetically. She deserves full credit for reviving the romance of the creative, innovative, entrepreneur. Ludwig von Mises, The Anti-Capitalist Mentality 3/8/16 26 Is cranky, as Mises often is, and yet provides a good summary of the absurd views which prevailed at the time (and are still common today). Mises is to be credited with many of the ideas that Hayek later improved upon, yet despite Mises’ rightful claim to originality, he is too dogmatic and cranky for my tastes. That said, I do learn from him and intend to read a great deal more of him in the future. Given the climate of world opinion when he articulated his ideas, Mises is without a doubt one of the most amazingly original and intellectually courageous thinkers of all time. It is not surprising that he was cranky and dogmatic given the opposition he faced. In judging Mises, it is worth considering that he was one of the few defenders of capitalism when John Dewey, arguably the most celebrated intellectual on earth at the time, was comparing the ethos prevailing in the Soviet Union to “the moving spirit and force of primitive Christianity,” even as Stalin was killing more people than Hitler and The New York Times was winning a Pulitzer Prize for Walter Duranty’s outright lies about the fact. The world had gone insane, and Mises was one of the last sane people on earth for a period of time in the 30s, 40s, and 50s. [Documentation on the Duranty lies: In 2003 the Ukrainian community attempted to have Duranty’s Pulitzer revoked but, to their great disappointment, failed. For a series of articles on the Ukrainian attempt to revoke Duranty’s Pulitzer, see: http://www.ukrweekly.com/revoke.shtml For a detailed account of the “Holdomor,” comparable in scale and intentionality to Hitler’s more famous “Holocaust” against the Jews, see http://www.unitedhumanrights.org/Genocide/Ukraine_famine.htm For a seven-minute film short on it see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFeqb0x7q1E Gareth Jones was a heroic journalist who denounced Duranty, and reported the facts of Stalin’s deliberate mass starvation of Ukraine, at the time: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gareth_Jones_%28journalist%29 His work was ingeniously discredited by the Soviets by a subterfuge in the U.S. press and then he was betrayed travelling companion (who turned out to have been a Soviet agent) while traveling in Asia and turned over to thugs who murdered him. Jones, and the Ukrainian Holdomor, should not be forgotten.] To return to our list of libertarian classics, Henry Hazlitt, Economics in One Lesson 3/8/16 27 Is rightfully a classic, a straightforward exposition of sound economic principles that should never be forgotten, regardless of one’s political predisposition. Henry Hazlitt, The Foundations of Morality Is far less well-known, but remains a classic statement of moral theory that deserves wider readership among people of all political dispositions. Hazlitt was a journalist rather than an academic, but he excels at creating coherent, common sense perspectives that remain useful many years later. Somewhat dated, but delightful in its enthusiasm for freedom, is Leonard Read, Anything That’s Peaceful As is Rose Wilder Lane, Give Me Liberty Rose Wilder Lane was one of a trio of women who, along with Isabel Patterson and Ayn Rand, largely launched the modern libertarian movement. Each published a major libertarian book in the mid 1940s, one of the darkest periods for classical liberal thought. Patterson’s book is least readable today, but still interesting. Rose Wilder Lane, The Discovery of Freedom Is also worthwhile; raised on the frontier (some believe she co-wrote her mother’s famous Little House series), she articulates more clearly than anyone else the ethos of personal responsibility and integrity that form the ethical core of personal behavior in the classical liberal worldview. One might also want to begin examining the contemporary journals and newsletters published by: The Cato Institute The Independence Institute The Fraser Institute The Pacific Research Institute Reason Magazine Reason Foundation The Mercatus Center And more; there is vast network of libertarian think tanks, whose work ranges in quality, but the best are providing cutting-edge intellectual content that is useful across the political spectrum. 3/8/16 28 Libertarian blogs worth reading include: Marginal Revolution, Tyler Cowan and Alex Taberrok Café Hayek, Don Boudreaux and Russ Roberts Econlog, Arnold Kling, Bryan Caplan The Austrian Economist, Pete Boettke, Chris Coyne, Peter Leeson, Frederic Sautet The Distributed Republic, a community blog that includes Milton’s grandson, Patri None of the above are hard-core ideological, they are all more focused on intellectual economic understandings of the world. Spending time browsing these blogs will introduce the reader to important perspectives on hundreds of issues that are not yet adequately represented in the public sphere at large. Becker/Posner Blog, Gary Becker and Richard Posner Is interesting, though not quite libertarian. Becker is certainly an advocate of markets, as is Posner in his way, but they both offend libertarian sensibilities in many ways, especially Posner. Finally, Liberty Fund has an excellent “Library of Liberty,” http://oll.libertyfund.org/ that provides free on-line access to an extraordinary library of classical liberal texts. Everyone should have read Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations J.S. Mill, On Liberty But few these days have also read classic works by: Herbert Spencer William Graham Sumner Cobden and Bright Lord Acton A. V. Dicey E. H. Hutt Edwin Canaan Frank Knight Samuel Smiles Carl Menger David Hume Adam Ferguson To name just a few. Once won has discovered the ongoing importance and relevance of the classical liberal perspective, it is worth going back to read 18th and 19th century 3/8/16 29 classics with a fresh eye, and to see just how sophisticated and relevant much of their thought remains today. 3/8/16 30