Music as Art in a Changing Culture

advertisement

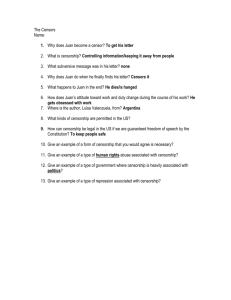

Music as Art in a Changing Culture By Eric Starr This is a transcript of a speech given at Loyola University, New Orleans on 20 April 2010. PART I: INTRODUCTION Good evening! It’s a pleasure to be here in New Orleans – truly one of my favorite cities in the world. Today, I will be speaking on music as art in a changing culture. This isn’t to say that I will avoid discussion of music from an entertainment and business perspective. But the overall focus will be on music as an art form. After 32 years studying and contemplating music, I have learned that life as a musician is a humbling experience. Composing music can be gutwrenching and learning an instrument is trial and error. In fact, it’s mostly error! When I would practice drums as a child my father—a musician himself—used to say, “Don’t rest on your laurels; Every day you must get up and build a new house.” I’ve been “building houses” for a good while now and I hope to build one with you tonight. As you may know, my orchestral piece entitled “They Are Afraid of Her” has been set to dance by professor Artemis Preeshl. A demonstration of her beautiful choreography can be seen this Friday and Saturday at The Louis J. Roussel Performance Hall. “They Are Afraid of Her” is part of a four-movement programmatic work that honors the nineteenth-century Lakota warrior Crazy Horse. My interest in Crazy Horse and Lakota culture stems, in part, from my love of music. From time immemorial, humans have had a strong connection to music and it’s safe to say that people and music have always and will always be intertwined … like the weave of a long braid. All Indian tribes, including Crazy Horse’s Oglala Lakota, associate music with spiritual power. Through song or olowan, Crazy Horse’s people have long communed with the invisible world. Among other things, music is used by the Lakota to doctor the sick and wounded and to help the supplicant “cry for a vision.” Song is especially powerful when used in the inipi or purification lodge and during the Wiwanyag Wachipi or sun dance; the latter is the most sacred of all Lakota rites. Whatever your views are on spiritual matters, one thing is for sure – using music to bring meaning to life is not only universal among human beings, it is ongoing and perpetual. PART II: THE BRAIN, MUSIC, AND CHANGE This begs the question: Has our relationship with music changed over time? On a biological level, it probably has not. Of course, both music and people have undergone enormous shifts and upheavals throughout the centuries. Values have changed, morals and mores have changed, laws have changed, technology has changed, the way we gather or congregate has changed, communities have changed, and even entire societies have undergone dramatic transformations. But, in a sense, the way music makes us feel has probably changed little. The human brain weighs about three pounds and contains some 100 billion cells. Of the many regions of the brain, the deep limbic system and prefrontal cortex give us the gifts of emotion and emotional control, respectively. On the whole, the emotional centers of the brain are no different today than they were in 2300 BC when the seeds of western music were sown in Sumerian citystates such as Ebla, where an ancient form of vocal music was developed. “From an evolutionary point of view, 4300 years is not a big distance to cause major changes in the brain,” writes Dr. Ottavio Arancio, professor of pathology and cell biology at Columbia University. He adds, “It would be unlikely that major differences have occurred in the brains of humans over this year span.” Moreover, his colleague, Larry Abbott, from the Center for Theoretical Neuroscience states, “Even a skilled anatomist would have trouble distinguishing between a brain from 2300 BC and now.” In order to know for sure, researchers would need to run a battery of tests on the brains of people living in 2010 and people living in 2300 BC. These test would include PET and MRI scans as well as electrophysiological testing (such as EEG) and neuropsychological testing. Obviously, this is not possible to do since there are no Mesopotamians hanging out on Bourbon Street drinking hurricanes … waiting to get their brains scanned. But through our understanding of evolution, we can reasonably infer that we possess the same brain as a healthy person from antiquity. The size and physical composition are likely identical or very nearly identical. Therefore, we can conclude that our underlying physiological response to music is probably very similar to that of our ancestors. Despite this, our ability to show, communicate, and control emotion may have evolved as civilization evolved and as our social skills evolved. Without a doubt, humans excel at change. Ask any archeologist or anthropologist and they will tell you that humans are a highly adaptive species. Moreover, as Dr. Arancio points out, “The brain is very plastic and therefore it is likely that a person who is more into music has certain areas of the brain more active than other people who are not into music.” Each person who becomes attracted to music develops a unique perspective on this art form; no two people hear and process music the same. Yet collectively, music history tells us that our perception, understanding of, and even definition of what constitutes music has changed spectacularly over the centuries. Moreover, the role music plays in various cultures—except perhaps tribal cultures—has changed significantly over the years. When considering change in music the important questions are: •Is it good, bad or both? •Should we even use such judgmental words (such as good and bad) to describe musical transformations? •Is change necessary or unnecessary? •What variables bring about change? •What about determinism vs. indeterminism? Can we evoke change or are we merely passengers in a musical car driven by unknown, unseen, and unforeseen forces? Are there “no accidents” in life as Carl Jung believed or is the whole darn thing an “accident?” •And what about the illusion of change? Are there musical mirages? Does some music simply masquerade as innovation? These are but a few questions that come to mind, when considering music as an ever evolving art form. PART III: WHO WE ARE AND THE ROLE OF MUSIC To shed light on these questions, we need to understand ourselves, our environment, and our interaction with our environment. If we don’t understand these elements, we simply cannot understand music. Overall, change in music occurs because of cultural flux. Culture is a particular set of beliefs, customs, practices, social behaviors, and attitudes that characterize a group of people. Increasingly, regionalism does not and can not fully determine one’s culture. Our technology has made humans irreversibly multi-cultural. In an age of fast, easy travel, immediate global communications, and instant access to information, profound cultural differences may occur between you and the guy in front of you at the check-out counter. Of course, this was not always the case. Even 75 years ago, persons were generally more insular and culturally isolated. Exceptions to this might include those who traveled extensively – usually for occupational reasons. For most people, it took time for new ideas, trends, and technology to become available to them. Today, one’s immediate surroundings have limited influence over one’s cultural development. These days, young people live on a steady diet of cross-cultural and cross-border exchange thanks to the radio, print media, television, computers, and now, social networking. In short, people today live in a global environment. Yet, society’s shift from localism to globalism does not reveal the full, rich story of music. If we are to fully understand change in music, we must dig deeper. In fact, if we are to comprehend our own musical mind, we must first answer the whopper question: Who are We? The Buddhist scholar and philosopher Alan Watts described the human experience as the quaking mess; In his lectures, he would often affectionately describe humans as insecure, nervous, and fearful creatures driven by ego. According to Freud: “…The ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world ... The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions.” In Freud’s psychic apparatus, the ego is the middle man, the stable one, the mollifying constituent who mitigates between the demands of the id and the superego. The ego is our consciousness, which is distinct from other beings and other things. However, in the eastern model, this ego is seen as an obstacle along the path to enlightenment. Why? Buddhist teachers, like Watts, warn us against embracing the ego or the “I” for many reasons. For one, the ego gives us a false sense of independence, sovereignty, and autonomy in a universe that is not “I” and “me” oriented but rather “we” and “us” oriented. We are all connected. We are all related. The Lakota say Mitakuye Oyasin: All my relatives. For the Lakota, the word “relatives” really means everything on earth. Consider our biosphere of which we are a part. It is completely integrated. If you start removing variables, the planet collapses on itself. We’re observing this now as extreme and erratic weather ravages the planet. There is a Native American proverb that goes: We do not inherit the land from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children. North American Indians believe strongly in the connection between humans and all things on earth. Tribes such as the Lakota have always viewed the earth or maka as a mother that nourishes and sustains us. Traditional Sioux Indians speak of a sacred hoop or medicine wheel that connects all things on earth including the four races of humankind, the four directions or cardinal points, the four elements of water, fire, earth, and air, the four stages of life, the four seasons, and so on. Among other lessons, the sacred hoop teaches one balance, harmony, beauty, and wisdom. It teaches one how to walk the Red Road or the road of goodness and health. By following the Red Road, one acknowledges one’s connection to all things in the universe. Nexus is also true on a subatomic level. We now know that, in our universe, seemingly distant events are connected; physicists even have a fancy name for this: quantum entanglement. This is at the heart of John Bell’s Theorem of nonlocality, which was first published in the mid sixties. In Newtonian physics, it was believed that an event which happens in one place cannot instantaneously affect an event someplace else. This is called locality and classical physics embraced this concept for over two centuries. Again, locality means that something that happens in the universe right now cannot have an immediate effect on something elsewhere in the universe; it must take time for the information to travel from one place in the universe to another. However, Bell's Theorem proved that particles at a distance, are in fact, connected because of "hidden variables." These variables are, at present, unknown to science but it's believed that entanglement occurs allowing distant particles to instantaneously interact, even if they are located light years away from one another. Einstein called this "spooky action at a distance." Okay… So what? That’s quantum mechanics; particles. Does non-locality explain who WE are? …Maybe. I think Alan Watts put it quite elegantly when he asked: “What are we? If you want to take a scientific point of view then you are an organism – about which we know very little. And the organism is inseparable from its environment and so you are the “organism environment.” In other words, you are no less than the universe. Each one of you is the universe expressed in the place, which you feel is here and now. You’re an aperture through which the universe is looking at itself and exploring itself. So when you feel that you are a lonely, put upon, isolated, little stranger confronting all of this, you have an illusory feeling because the truth is the reverse. You are the whole works that there is and always was and always will be. Only … just as my body has a little nerve end here in my finger – which is exploring and which contributes to the sense of touch – you are just a little nerve end for everything that’s going on. But we feel it the other way around… What’s going to happen when you are dead? What do you mean you? If you are basically the universe, that question is irrelevant. You never were born and you never will die.” This is quite a definition of self, isn’t it? Then again, Watts also said that “Trying to define yourself is like trying to bite your own teeth.” Nevertheless, what I’m presenting here is a picture of reality as I see it. This is a picture of the self, of culture, of our environment, and the relationship between the all of this. So now you might ask, “How does music fit into all of this?” Music is an expression of the self … and if you believe that you are a nerve end for the universe then music is an expression of the universe. Period. The next logical question is: What is music? There is a misconception that music is sound. This is not entirely true. Music is a combination of sound or vibrations and silence. Marcel Marceau put it perfectly when he said, “Music and silence combine strongly because music is done with silence, and silence is full of music.” Indeed, silence is the fabric upon which notes are woven. What is the role of this “sound and silence” in society? This is open to interpretation and debate. Many believe that music’s objective is to communicate something to a listener or to an audience: to communicate an idea, a story, a message, or simply an emotion. Robert Schumann exclaimed, “It is music’s lofty mission to shed light on the depths of the human heart.” Without a doubt, music is a powerful tool that can be used to convey matters of the heart. Music awakens our senses, stirs our memories, and energizes us … or deflates us. It speaks to our dream self or unconscious mind and it encourages abstract thought processes. It even stimulates compassion and empathy...or hatred. But why? And how? Music arouses many areas of the brain. And since our brain is constantly seeking pleasure, it searches then attaches itself to music that it finds interesting. Once it finds a match, it produces “feel-good chemicals” called endorphins that allow you to experience gratification from music. According to Dr. Daniel Levitin, Author and Associate Professor of Psychology at McGill University, “The brain is a giant prediction device and it’s trying to figure out what’s going to happen next. The thing to realize is that all of us are descended from ancestors who like learning and music is a kind of experimental laboratory for the brain really.” What also appeals to our probing brains is music’s immediacy. Balzac wrote that “music … communicates ideas directly, like perfume.” To describe music as perfume is interesting to me because I sometimes associate music with smell. When I was little, I used to drum on an old, depression era leather chair in my parent’s home while I listened to Beatles records. To this day, when I hear the songs I used to play along with—like “Please, Please me” and “Love Me Do”—I swear I can smell that old leather chair. It seems our brain functions quite well when it’s stimulated by music. Researchers such as Dr. Lola Cuddy at Queens University in Ontario have studied Alzheimer patients who don’t remember who visited them yesterday in the nursing home. Or who cannot identify simple foods such as an apple or a carrot. Yet, these patients can remember songs they danced to—note for note—in their youth. Music provoking a smell? Music stimulating the recollections of an Alzheimer patient? This is all evidence of music’s ability to etch indelible memories into our brain. PART IV: THE MUSIC INDUSTRY, CENSORSHIP, AND ARTIST VIABILITY When we speak about music’s communicative power, we must also recognize it’s ability to sell a product, or a political, spiritual, religious, or military agenda. Music is quite possibly the most effective propaganda tool in history and this is what the entertainment business has long seized upon. Frank Zappa summed it up best when he said: “The single most important development in modern music is making a business out of it.” The popular music business has gone through monumental shifts since the days of “song pluggers” and Tin Pan Alley publishers. But since our time is limited, let’s look at some of the critical changes that have taken place in just the last few decades in the recording industry. As I see it, musicians have long struggled to find their seat at the roundtable of big business. In the United States, we live in a culture that values gimmickry over innovation. But the rub is that many gimmicks are branded as innovative. Moreover, these gimmicks are sold with enthusiasm to an unsuspecting, largely uneducated public. For example, when I watch the Grammy’s, I see electrifying stage shows and wellcrafted dance routines. But musically speaking, most of the acts lack originality or invention. And yet, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences would have us believe that we are being treated to performances by the world’s most ground-breaking artists. I simply do not buy into this mythology. In a capitalist society, the aim is to sell goods and services at a profit. In this system, music is just another product on the shelf. I have always been uncomfortable with this fact of life but I remind myself that record labels are businesses not nonprofit organizations. They are in the business of making money; they’re not patrons of the arts. However, fast talking business men (and women) have a habit of making artists believe that they are vital to the recording industry’s web of life, when in fact, the majority of artists are disposable players in a cat and mouse game of mergers and acquisitions. In the late ‘80’s, there were six major record labels but in 1998, PolyGram Records was absorbed by Universal Music Group and the “Big Six” became the “Big Five.” Then in 2004, The “Big Five” became the “Big Four” after Sony and BMG entered into a joint venture. In 2008, Sony acquired all of BMG and the “big four” became: Warner Music Group, EMI, Sony Music Entertainment, and Universal Music Group. All of these labels have subsidiaries. And as you might imagine, many of these subordinate companies have come and gone or been restructured over the years as well. Such is the case with Atlantic Records, once an independent label and now a subsidiary of Warner Music Group. Atlantic was the home of Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, and other jazz legends. But the label shifted gears and stopped recording and releasing jazz albums altogether in the early 2000’s. Why? It simply wasn’t profitable. Sometime in the 1990’s music marketed by the majors also started to become more generic and safe. That isn’t to say that all the music produced and sold by these corporations was poor, or for that matter, that all of the music produced by these companies prior to 1990 was stellar. But, by and large, major labels gradually shifted away from artist development, and instead, embraced a policy of manufactured hits. This resulted in a proliferation of sterile or flavorless releases particularly in the modern R&B, modern rock, and adult contemporary genres. Also in the ‘90’s, tentative and cautious signing policies by major labels created a flood of unsigned artists looking for a home. The best of them eventually found their way into the independent or “indie” market, which flourished in this decade. Here, many of the more quirky–and frankly interesting–artists who couldn’t get signed by the big boys now had an outlet for their music. But is indie really indie? Only major holding companies have major distribution. In search of improved public exposure and revenue, many indie labels have naturally become seduced by the wide distribution that only the majors can offer. Currently, most independent labels have become dependent on the largesse of the majors; several indie labels have even been purchased by the majors. Suppop records is one such example. Warner Brothers has a 49% stake in the company. Moreover, the majors’ mainstream mindset has influenced the indie market resulting in garden variety indie releases. I always thought indie labels were the outlaws, the renegades, the insurgents of the recording industry. Unfortunately, few of them truly are. Whether indie or major, I never met an A&R man who wasn’t worried about losing his job. Because of high turnover, artist & repertoire has embraced a short-sighted, bankable mentality. In the big picture, record labels often want something for nothing and artists are cajoled into handing over their best work for mere “smoke and mirrors” in return. The old days of taking a chance on an artist and assisting them by developing their image, and their musical catalog, is an outmoded business model today. In the last decade, musical piracy and file sharing became an epidemic as well. However, it was legal sales of music—via the internet—that changed the rules of musical commodification. Most consumers now purchase music one song at a time. The average listener seems less interested in entire albums. And because of iTunes and other online vendors, brick and mortar retailers have gone belly up. The consumer has fully embraced technology that is immediate and selective. Browsing for CD’s in a store has gone the way of the dodo. In New York, when I saw Tower Records at Lincoln Center and Virgin Megastore in Union Square close their doors, I knew that the industry had finally made a metamorphosis from in-store to online. This new world order has befuddled major labels who have seen their CD sales plummet and digital downloads fail to fill in the gap. As we sit at the crossroads of change, major labels are struggling to redefine their role in a rapid moving digital revolution. But how does an artist stay viable in this musical whirlwind? First you need to make a distinction between the artist and the craftsmen. Up until now, I have used the term “artist” to essentially mean both. But in fact, they are different beasts. In his autobiography, drummer Bill Bruford writes: “Most practitioners tend to fall instinctively into either the artist or the craftsman camp. On the one hand lies the Romantic ideal of the artist in his garret, driven by demons that won’t let him sleep at night because he has imagined the future and must express it or he’ll explode. He works continually to public indifference or open ridicule, scraping by with enough money from some tedious related labor, perhaps in the face of increasing illness – Beethoven and his deafness; Stravinsky hearing open laughter during the premiere of The Rite of Spring in Paris; Gauguin, Van Gogh – before he too succumbs, to be buried in a pauper’s grave, like Mozart is supposed to have been, or cut off in his prime, like Jimi Hendrix, Scott LaFaro, Charlie Parker, Janis Joplin, or Michael Hutchence.” “On the other hand,” Bruford contends, “We have the industry craftsman – mercenary, canny, certainly going for success well within his lifetime, looking for that spark that will capture the public imagination, scouring modern society for that hook line, that topic, that slant, that will make him millions. A useful business man, he lives by trying to guess what the public wants and then supplying it, be he Irving Berlin with ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band,’ Paul Whiteman, who was sure that jazz could be a big thing if only he could get the jazz out of it, a songwriter in the Brill Building in Manhattan in the late 40’s, putting words in the mouths of appealing young men all called Bobby, or perhaps Mitch Miller with his late-50’s American pop, or producers Trevor Horn or Simon Cowell. Artist and craftsman co-exist nominally within the music industry, but they are as unalike as chalk from cheese, as art from money, as God from Mammon…Neither artist nor craftsman tends to make much effort to understand the other, and each has developed whole vocabularies to express their ‘otherness’: pretentious and self-indulgent on one hand; mercenary and mundane on the other.” The one common thread is that both the artist and the craftsman must traverse the tight wire of change. They must also live within the confines of the dominant culture and its ever-evolving moral principles. When an artist or craftsman finds himself at odds with the attitudes and values of the majority, their work may become censored. In earlier times, this dilemma applied mostly to free thinking artists who were already marginalized by society. The underground jazz and blues movements in the first quarter of the twentieth century exemplifies this. But since the rock-n-roll and so-called “urban” music revolutions, mainstream artists have found themselves caught in the web of censorship. With music, the most common forms of censorship are word covering, airplay bans, and the use of parental advisory stickers. The latter is the legacy of the PMRC or Parents Music Resource Center who first introduced this concept in 1985. On the surface, censorship seems like common sense especially when considering the impressionability of children. Why would any conscientious parent want their kids influenced by lewd and crude music: by people who use foul language, objectify women, preach violence, rape, hatred, etc.? But censorship is a slippery slope and the lines of demarcation between art and the obscene have always been hazy (at best). Who gets censored and who stands on the high hill making these decisions? Are these decisions in the best interest of society? And is all censorship equal? Is there such a thing as “mild” censorship vs. “extreme” censorship? Moreover, does all censorship suppress art? If so, to what degree? What are the cons AND the pros of censorship? There must be something good that comes out of it … Or no? Is it flat out wrong? Who gets hurt by censorship? Is it just the muzzled artist and his adoring fans that suffer or is there something else at stake? Something deeper and more profound that is lost or compromised when we censor? On the other hand, who might benefit from censorship? Innocent kids? Uptight parents and political officials? Do laws that place limits on freedom of speech promote peace and harmony in a diverse, often factionalized, and easily ignitable society? We could argue these points until snakes grow legs. In the United States, the FCC or Federal Communications Commission states that: Obscene material is not protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution…The Supreme Court has established that to be obscene, material must meet a three-pronged test: 1. An average person, applying contemporary community standards, must find that the material, as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest. 2. The material must depict or describe, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable law -AND3. The material, taken as a whole, must lack serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value. The third “prong” leaves a lot to interpretation. It essentially asks the question: what is art and what is not? I cannot think of a harder question to legitimately answer because art is simply too subjective and personal; one man’s art is another man’s trash, you know? We can say that most artistry thrives on freedom of expression, whether it’s a novel, a painting, a sculpture, a photograph, or a piece of music. In most cases, art cannot achieve its full potential or become fully actualized if external restrictions are placed upon the artist. We all self-edit or self-censor. That is part of the artistic process. As Hemmingway said, “The most essential gift for a good writer is a built-in, shock-proof, shit detector.” Can I say that on stage? But for some, external censorship suffocates the artistic process and the artistic impulse. It boxes them in; it dries up the creative wells. Others find clever ways around it; they somehow build art into the censorship and censorship into the art. Then there are those who use censorship as a barometer for their success. For those artists bent on petting the cat the wrong way, censorship validates the radical or inflammatory nature of their work. The Marquis de Sade was a perfect example of this. In music, heavy metal, punk, and hip-hop have all produced confrontational artists over the last 35 years who gained credibility with fans, in part, because of censorship. In the recording industry, I think it’s best to remember the double edged sword of censorship. Whether you support it or not, the basic facts cut both ways; censorship does reduce the circulation of “dubious” songs and/or albums, but it also yields forbidden fruits. Like some pharmaceuticals, censorship has a way of causing rebound effects. In other words, censorship often draws attention to that which you seek to screen out. And again, who decides what is an “acceptable” artistic statement and what is not? Any way you frame it, censorship is a sensitive issue, like gun control, abortion rights, and the separation of church and state. As such, the debate will rage on. Considering the rapid ascendancy of digital media and the possible pitfalls of censorship, how does an artist or craftsman stay viable? The truth is—and this is not a copout— there is a certain amount of dumb luck involved. This is especially true of the committed pop musician who’s career must shift with, or be strong enough, to weather trends in fashion and hair, as well as music production techniques. Pop artists who don’t embrace current technology—for example— often fall out of favor. In his autobiography, Bill Bruford—a forty-year music veteran—sums up artist viability perfectly. According to him, “The music business is, and has always been, highly volatile, a continual struggle for control as to whether the content of the mass media is to be decided by established authorities, be they the BBC, Sony Records, or Bugs Bunny, or by popular demand through the market. The role, importance, and market value of the individual musician fluctuates alarmingly within that, depending on how valuable his services may be at any given time.” Because of power struggles within the industry and external factors beyond our control, we must learn to wear our disappointments well. But If we pursue excellence in our work and maintain a good sense of humor we increase our chances of remaining active “on the scene.” For guys like me who float between the academic and the popular, who write jazz tunes, chamber pieces, and longwinded symphonic works … who play in smoky jazz rooms, dodgy rock clubs, and formal concert halls … well, we’re pretty much misfits, I suppose. But I wouldn’t have it any other way. To defy classification is to retain some individualism in a business that constantly and stubbornly seeks to define itself by broad labels or tags that, in fact, tell you very little about the person and their work. PART V: THOUGHTS ON COMPOSITION AND THE FUTURE OF MUSIC With regard to composition: Those who write outside of popular music must accept that their work will have limited ability to be heard. Your audience becomes your peers, music students, and a relatively small percentage of the lay public who avoid mainstream offerings. But who said composing music is about mass appeal and adoration anyway? I mean, is that what we’re really after? Maybe composing means something else. Maybe composing helps to bring order to our lives whether we painstakingly construct a work of art one scratch of ink at a time or whether we act as a channel through which the music of the universe flows freely. Stravinsky considered his Rite of Spring to be the product of the latter. He wrote, “Very little immediate tradition lies behind Le Sacre de Printemps. I had only my ear to help me. I heard and wrote what I heard. I am the vessel through which Le Sacre passed.” Many composers write music to make sense out of internal chaos. In a way, composition is like picking up a cluttered, disorganized room or alphabetizing the book shelf. It serves a very real psychological need to sort, organize, and systematize one’s thoughts. For the listener, a work of art may have a similar effect. It may bring order, stability, and peace of mind to an otherwise topsy-turvy life experience. In other words, music and art serve as counterpoint to the quaking mess. But does music answer questions about X, Y, or Z? Does it help us to understand ourselves—the environment organism— more clearly? Some might argue that it does; that music offers rare insights into the human condition. I tend to agree with Leonard Bernstein who wrote that “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is the tension between the contradictory answers.” For what it’s worth, the ultimate goal of my work is not communication. If that’s your goal, you open yourself up to a misreading and who likes to be misinterpreted. Each listener grasps music uniquely and, like snowflakes, no two listeners are the same. The way we comprehend music depends on thousands of factors, many of which are inscrutable. Therefore, I seek a different objective as a composer … and a drummer or “musician” for that matter. Borrowing a philosophical concept from Indian musician Gita Sarabhai, John Cage said: “The goal of music is to sober and quiet the mind so that it may become susceptible to the divine.” When I first heard this quote, I said: AH-HAH! This is what I’ve been looking for; this is what I’ve been stammering to say all my life. I couldn’t agree more with this sentiment. In my opinion, music should enchant us, but at the same time, it should quiet us or calm us. It should sober our minds, which are inebriated by illusion and self-centered, “I” oriented thinking. I may be naive, but I believe that music has the power to aid us in ridding ourselves of mental toxins such as anger, despair, fear, pessimism, and more. In general, music should open us up rather than shut us down and it should bring us closer to a state of enlightenment. Cage uses the word “divine.” For many, of course, divinity is synonymous with God; a supreme being. For me, the divine is simply the beautiful mysteries of the universe. I enjoy exploring these unknowns, in my own abstract way, through musical composition. Pierre Boulez wrote, “Music is a labyrinth with no beginning and no end, full of new paths to discover, where mystery remains eternal.” This mystery inspires me and it is a powerful catalyst for artistic creation. And the future of music? Compositionally, we will see the continued development of stylistic hybrids. This will all be the result of cultural and ethnic blending as technology makes our world smaller and even more interactive than it is now. In the future, composers will continue to experiment with note and chord combinations that cull from both tonality and atonality. Perhaps quarter-tonal music will become more prevalent in an attempt to move beyond the grid of the twelve-tone system. Other composers may experiment with nonconforming temperaments in order to bring new meaning to intervals, pitch, and tuning. But beyond the academic, it is musical texture that will likely bring about the greatest change in the 21st century. In fact, texture may be the only frontier that still holds some novelty. Harmony—both tonal and atonal—rhythm, counterpoint, and musical structure have all been pretty thoroughly explored as well as traditional instrumentation. But through the use of digital technology, novel sounds will emerge and this will encourage the use of new textures, timbres, and musical layers. Of course, we’ve already seen this occur but it will not abate. Since the emergence of the electric guitar in the late 1940’s, our ears have gradually become conditioned to amplification and louder decimal ranges. Fast forward to the 21st century. We now have software applications on our home computers that can generate virtual guitars and dozens of other virtual instruments. The most user-friendly application of this kind is Apple’s very popular GarageBand, which allows students to use factory prepared “drag-anddrop” loops to create entire compositions without actually writing any music of their own. And it sounds good! Computer drummers keep perfect time and those pesky guitars don’t go out of tune. Plus, everyone shows up on time for rehearsal. In the future, the production of new and fresh sounds will follow in lockstep with our latest gadgets and gizmos. And increasingly – the firewall between man and machine will erode as humans become their machines and machines become human. Have you heard about the recent iPhone study at Stanford University? This study showed that 10% of students were fully addicted to their iPhone and 34% gave themselves a four on the five-point addiction scale. Another 32% worried about addiction to their iPhone and a whopping 75% confessed to sleeping with their iPhone. Are we anthropomorphizing our technology or what? How far will this go? Maybe we’ll start marrying our cell phones? It’s almost certain that, in the future, we will see robotics infiltrating a once human only concert stage. Guitarist Pat Metheny’s ground-breaking Orchestrion project offers a taste of what’s to come. On his recent tour, he is seen performing with an all robot ensemble thanks to modern solenoid technology. What does this mean for the journeyman musician and the virtuoso alike? Are we expanding our musical palette or rendering ourselves obsolete? Probably a little bit of both. In the end, I’d like to think that Charles Ives was right when he wrote, “The future of music may not lie entirely in music itself, but rather, in the way it encourages and extends, rather than limits, the aspirations and ideals of the people, in the way it makes itself a part with the finer things that humanity does and dreams of.” I know that I’ll keep dreaming and I hope you do as well. Thank you for listening.