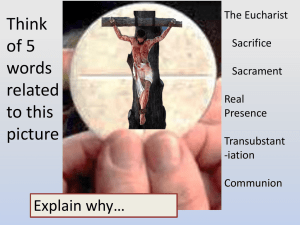

Year of the Eucharist

advertisement