GI disorders notes

advertisement

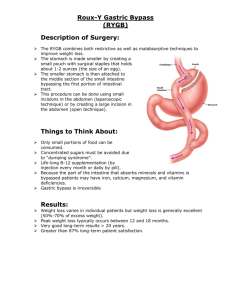

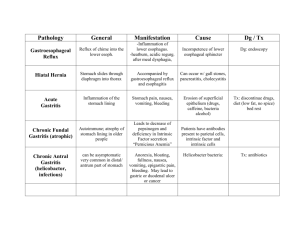

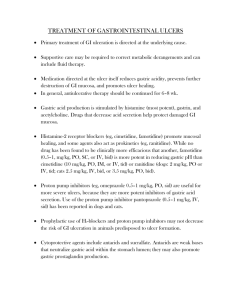

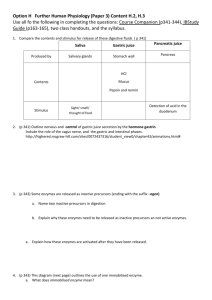

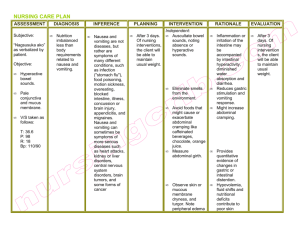

My Study Guide! PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE (PUD) What is it? PUD is a condition characterized by erosion of the GI mucosa resulting from the digestive action of HCl acid and pepsin. It involves ulceration, circumscribed breaks in the mucosa, occurring in the duodenum (duodenal ulcers), the stomach (gastric ulcers), and less commonly, the distal esophagus and the jejunum. PUD develops only in an acid environment. Patients with pernicious anemia and achlorhydria rarely have gastric ulcers. People with gastric ulcers have normal to less than normal gastric acidity compared to people with duodenal ulcers. Still, some intraluminal acid would seen to be necessary for a gastric ulcer to occur. Risk Factors-Smoking, aspirin, spicy foods, stress, Emphysema, rheumatoid arthritis, cirrhosis, etc. Often asymptomatic! Duodenal Ulcers-When pain does occur, it is described as “burning” or “cramplike”. Most often located in the midepigastric region beneath the xyphoid process. Gastric Ulcers-Pain described as “burning” or “gaseous”. Located high in the epigastrium. Physiologic Stress Ulcers-Acute ulcers. Develop during a major physiological insult such as trauma or surgery. Peak incidence for duodenal ulcers is between the ages of 25-30 and for gastric ulcers, those older than 50 years. EtiologyThought to result from Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection. Other factors are related to gastric acid secretion like: Altered gastric acid and serum gastrin levels Tobacco smoking and alcohol use Use of aspirin, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and corticosteroids Genetic predisposition Psychosomatic or psychological factors (chronic anxiety, Type A personality) Comparison: 1 Gastric Ulcers-Less Common Lesion Location Gastric Secretion Incidence Superficial, smooth margins: Round, oval, cone-shaped Usually antrum. Also in body and fundus of stomach. Normal to ↓ secretion Greater in women Peak age 50-60 More common in lower socioeconomic status & unskilled laborers. ↑ with smoking, drug and alcohol use. ↑ with incompetent pyloric sphincter and bile reflux. ↑ with stress ulcers after severe burns, head trauma, major surgery. Clinical manisfestations Burning, gaseous pressure in high left epigastrium and back and upper abdomen. Pain 1-2 hours after meals. If penetrating ulcer, aggravating of discomfort with food. Occasional nausea and vomiting, weight loss. Recurrence rate Complications High Hemorrhage, perforation, outlet obstruction, intractability. Aspirin, corticosteroids, NSAIDS(ibuprofen, Serpasil) Possible/probable culprits? Duodenal Ulcers-More Common Penetrating First 1-2 cm of the duodenum. ↑ secretion Greater in men-Increasing in women (postmenopausal) Peak age 35-45 Associated with psychological stress. ↑ with smoking, drug and alcohol use. Assoc. with other diseases (COPD, Pancreatic disease, hyperparathyroidism, ZollingerEllison syndrome, chronic renal failure. More often in Type O blood! Burning, cramping, pressure-like pain across mid-epigastrium and upper abdomen. Back pain with posterior ulcers. Pain 2-4 hours after meals and midmorning. Sometimes in the midafternoon, middle of the night, periodic or episodic. Pain relief with antacids and food. Occasion nausea and vomiting. High Hemorrhage, perforation, obstruction. H pylori, genetics, People with Type O have ↑ incidence. Complications!! Hemorrhage-Most common. Develops from erosion of the granulation tissue found at the base of the ulcer during healing or from erosion of the ulcer through a major blood vessel. Duodenal ulcers account for most of these. Take VS every 15-30 minutes. Maintain IV infusion. Monitor HCT and HGB. Record I & O. Prepare patient for possible endoscopy or surgery. Perforation-The most lethal complication. Most commonly seen in large penetrating duodenal ulcers that have not healed and are located on the posterior mucosal wall. Most often located on the lesser curvature of the stomach. The size of the perforation depends on how long the patient has had the ulcer. Sometimes spontaneous sealing occurs. This is 2 from large amounts of fibrin being produced and leads to fibrinous fusion of the duodenum or gastric curvature to adjacent tissue, most often the liver. OUCH!! How can you tell this has occurred? Sudden and dramatic onset! The patient experiences sudden, severe upper abdominal pain that quickly spreads throughout the abdomen. The abdomen muscles contract, appearing rigid and boardlike. The patient’s respirations become shallow and rapid. Bowel sounds are usually absent. Referred pain. Drawing up of knees. Nausea and vomiting mayyyy occur, but not necessarily. Bacterial peritonitis may occur in 6-12 hours!! Need to stop the spillage of gastric or duodenal contents into the peritoneal cavity and restore blood volume. NG tube to provide continuous aspiration and gastric decompression. Replace blood volume with lactated Ringer’s and albumin solutions. If patient has history of cardiac disease, ECG monitoring or pulmonary artery catheter. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Pain Meds. Gastric Outlet Obstruction-If the ulcers are located in the antrum and the prepyloric and pyloric areas of the stomach and duodenum, this can occur. In the early phase, gastric emptying is normal or near normal. The patient usually has a long history of ulcer pain. If the ulcer pain is of short duration or if there is complete absence of pain, this is more indicative of malignant obstruction. Pain worse at end of day as the stomach fills and dilates. Sometimes relief via belching or self-induced vomiting (with food particles from even the meal the day before!). There is often an offensive odor (after all, the food is old!) The patient who vomits a lot will be anorectic with evident weight loss. Will probably complain of thirst and a bad taste in the mouth. Constipation is also a common complaint. The patient may show a swelling in the upper abdomen. Loud peristalsis can be heard with visible peristaltic waves. If patient is NPO, check patency of NG tube. Reposition patient from side to side. Decompress the stomach! Correct fluid and electrolyte imbalances. Measure gastric residue periodically. Clamp the tube overnight for 8-12 hours; measure gastric residue in the morning. If aspirate below 200 ml, normal. Patient can resume oral intake. (Begin oral liquids at 30 ml/hour). Pain relief Pyloric obstruction treated nonsurgically by balloon dilations via an endoscope. H2R blockers, PPIs. A lot of vomiting = ALKALOSIS! Watch that! How to Diagnose? (Besides H & PE) Endoscopy! Most often used. Upper GI. H.Pylori testing. (Breath, urine, blood, tissue) Upper GI Barium Contrast-(Really kewl to check for gastric ulcer obstruction) CBC-(Anemia?) Urinalysis Liver Enzymes-(Liver probs like cirrhosis?) Serum Electrolytes Maybe a serum amylase test to check pancreatic function. 3 How to Treat? Goal is to maintain mucosa, elevate pH, inactivate pepsin, and relieve pain! Patient needs adequate rest, dietary modifications, drug therapy, elimination of smoking, and long-term follow-up care. Aim is to decrease gastric acidity. Requires many weeks of therapy in ambulatory setting. Pain may disappear quickly but ulcer healing is slower. Find out if the ulcer is healed via x-ray or endoscopic exam. Eliminate stressors! Food! Food! Food! Bland diets are best-Six small meals a day. Eliminate alcohol and caffeine-containing products. Foods known to upset: hot, spicy foods and pepper, alcohol, carbonated beverages, tea, coffee, and even broth from meat extract. Foods high in roughage like raw fruit, salads, and vegetables, may irritate! However, if well chewed, seldom a problem. Protein-Good neutralizing food. However, it stimulates gastric secretions. Carbs and fats are the least stimulating to HCl acid but do not neutralize well. Milk is okay for PUD. Drug therapy-Meds remove excess hydrogen ions so less chance of tissue injury. HCO secreted by mucosa helps neutralize acid. Think buffer here. Acute exacerbation? If recurrent vomiting or gastric outlet obstruction, place NG tube in stomach with intermittent suction for 24-48 hours. Replace fluids and electrolytes via IV until oral feedings tolerated. May need transfusion. 5-year follow-up program recommended after acute exacerbation. SURGERY!! Less than 20% patients need surgery. Why need it? Intractability-when an ulcer fails to heal or comes back after therapy. History of hemorrhage or increased risk of bleeding during treatment. Prepyloric or pyloric ulcers because of their high recurrence rates. Concurrent conditions (burns, trauma, sepsis) Multiple ulcer sites. Drug-induced ulcers. Possibility of malignant ulcer. Obstruction. What kinds? Partial gastrectomy, vagotomy, pyloroplasty? Great picture of these on Page 1041! Vagotomy-The severing of the vagus nerve. Can be total (truncal) or selective. In a truncal Vagotomy both the anterior and posterior trunks are severed. In a selective 4 Vagotomy, a nerve is cut at a particular branch of the vagus nerve, resulting in denervation of only a portion of the stomach, such as the antrum or the parietal cell mass. This decreases gastric motility and gastric emptying. Pyloroplasty-This consists of surgical enlargement of the pyloric sphincter to facilitate the easy passage of contents from the stomach. Most commonly done after Vagotomy or to enlarge an opening that is constricted from scar tissue. If done with a Vagotomy, it increases gastric emptying. Billroth I-AKA Gastroduodenostomy-Partial gastrectomy with removal of the distal 2/3 of the stomach and anastomosis of the gastric stump to the duodenum. Billroth II-AKA Gastrojejunostomy-Partial gastrectomy with removal of the distal 2/3 of the stomach and anastomosis of the gastric stump to the jejunum. The preferred surgical procedure because the duodenum is bypassed. The antrum and pylorus are removed in both procedures. NOTE: With partial removal of the stomach, you lose intrinsic factor! This means pernicious anemia! Will probably require life-long B12 (cobalamin) injections. Post-Op complications: Dumping Syndrome-It is the direct result of surgical removal of a large portion of the stomach and the pyloric sphincter. Reduced reservoir capacity of the stomach. More common after Billroth II procedure. Associated with meals having a hyper-osmolar composition. Stomach can’t control the amount of gastric chyme entering the small intestine. Because of this, a large bolus of hypertonic fluid enters the intestine and causes fluid to be drawn into the bowel lumen, creating a decrease in plasma volume. Symptoms usually occur 15-30 minutes after a meal. Patient usually feels weak, sweaty, may have palpitations and dizziness. This is because of the sudden decrease in plasma volume. The patient may complain of abdominal cramps, borborygimi (loud abdominal sounds like we’re often annoyed with while in a quiet classroom!), and the urge to defecate. Symptoms usually last an hour after a meal; no longer. Postprandial hypoglycemia-A variant of the dumping syndrome. The result of uncontrolled gastric emptying of a bolus of fluid high in carbs into the small intestine. Hypoglycemic-like symptoms. Bile reflux gastritis-Prolonged exposure to bile=Damage to gastric mucosa. Can actually CAUSE peptic ulcer! May result in back diffusion of hydrogen ions through the gastric mucosa. Give cholestyramine (Questran) either before or with meals. Sometimes aluminum hydroxide antacids too! Post-Op foods? 5 No fluids with meals! Dry foods with low-carb content. Moderate protein and fats. If hypoglycemic, fluids or candy. Limit the amount of sugar in meals. Eat small, frequent meals. Post-Op Care? NG tube for decompression. Check patency!! Observe gastric aspirate-May be bright red at first with gradual darkening within first 24 hours after surgery. Color changes to yellow-green in about 36-48 hours. Observe for decreased peristalsis. Absent bowel sounds? Lower abdominal discomfort? Obstruction? Monitor I & O, VS. Ambulation encouraged. Notes on the Elderly Increased use of NSAIDS that may cause PUD. Pain may not be the first symptom! May be frank gastric bleeding or a decrease in hematocrit! [Norm:Male-41.5% to 50.4%. Female-35.9% to 44.6%] Morbidity and mortality rates higher-Decreased ability to withstand hypovolemiaChronic illnesses (CV, Pulmonary) Treatment and management about the same as in the younger folks. Other Problems- Gastritis Esophagitis Bezoars-Hard mass of tangled stuff. Ewwwwww GU Quickees! Appendicitis-Inflammation of the appendix, a narrow blind tube that extends from the inferior part of the cecum. More common in males than females. Most common cause is 6 obstruction of the lumen by a fecalith (a piece of poop, for goodness sake!). Can also be obstructed by foreign bodies, tumor of the cecum or appendix, or intramural thickening caused by hypergrowth of lymphoid tissue. Thus, distention, venous engorgement, accumulation of mucus and bacteria…..Gangrene and perforation! Pain!!! Periumbilical pain followed by nausea, vomiting. Anorexia. Pain persistent and continuous, localized at McBurney’s point. Localized tenderness, rebound tenderness, muscle guarding. Rovsing’s sign from palpation of the LLQ causing pain to be felt in the RLQ. Complications are perforation, peritonitis, abscesses. Need complete history and PE, differential WBC count, urinalysis to rule out GU probs. Need immediate surgical removal! Appendectomy time! Peritonitis-Results from localized or generalized inflammatory process in the peritoneum. Primary causes are blood-borne organisms, genital tract organisms, cirrhosis with ascites. Secondary causes are appendicitis with rupture, blunt or penetrating trauma, diverticulitis with rupture, Ischemic bowel disorders, obstruction in the GI tract, pancreatitis, perforated peptic ulcer, peritoneal dialysis, post-op (breakage of anastomosis). S & S/Tests: Severe localized or diffuse abdominal pain. Paralytic ileus. Bowel sounds decreased or absent. Fever, tachycardia, chills (sepsis?) Shallow, guarded respirations. Dehydration and ACIDOSIS, late manisfestations. WBC count (leukocytosis, leukopenia) Radiograph, Peritoneoscopy(endoscope via a stab wound in the abdomen) Treat with antibiotics, NG suction, analgesics, IV fluids, Surgery. May need TPN. Life-threatening complications include bowel obstruction, renal failure, respiratory insufficiency, shock, and in some cases, liver failure. Gastroenteritis-Inflammation of the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramping, distention. May see fever, ↑ WBC, blood or mucus in the stool. Patient will need to be NPO until vomiting stops. Will need IV replacement. Afterwards, foods with glucose and electrolytes (Pedialyte?). Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. These disorders are characterized by chronic, recurrent inflammation of the intestinal tract. Cause remains unknown. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)-Excessive reflux of HCl acid into the esophagus. Incidence increases with age. Usually results from an incompetent LES, pyloric stenosis, or motility disorder. Associated with Hiatal Hernia. S & S- 7 Pyrosis Regurgitation of sour-tasting secretions (BLECHHH!) Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and odynophagia (pain on swallowing). Symptoms sometimes mimic a heart attack! Treatment Meds (antacids, H2-receptor antagonists, PPIs) Low-fat, high-fiber diet. Avoid spicy or acidic foods. No alcohol, caffeine, tobacco. Avoid food and drink 2 hours before bedtime. No lying down right after eating. Elevate the head of the bed on 6- to 8- inch blocks. Lose weight if obese. If symptoms persist, surgical repair! (fundoplication) Portal Hypertension-Characterized by increased venous pressure in the portal circulation, as well as splenomegaly, large collateral veins, ascites, systemic hypertension, and esophageal varices. Elevated pressure in the portal vein associated with increased resistance to blood flow through the portal venous system. Incidence is similar to that for cirrhosis. Ascites Shifting dullness or fluid wave on abdominal percussion. Dilated abdominal vessels radiating from the umbilicus. Enlarged, palpable spleen. Bruits detected over the upper abdominal area. Treatment Meds (may include diuretics) Measure and record abdominal girth (ascites!) Elevate lower extremities, wear support hose Give salt-poor albumin to raise serum albumin level. This increases serum osmotic pressure, helping to reduce edema by causing ascitic fluid to go back to the bloodstream so it can be eliminated by the kidneys. May need paracentesis (removal of fluid) May need peritoneojugular (LaVeen) shunting. Not used often. Intestinal tubes used for decompression! Harris Tube-aspirating holes, black silk tie Miller-Abbott Tube-Double lumen Cantor tube-aspirating holes 8 Define Pyrosis-Heartburn Eructation-Belching :-\ Steatorrhea-Bulky, foul-smelling, yellow-gray, greasy stools with putty-like consistency; float in water. Ewwwww Diverticulosis/Diverticulitis A diverticulum is a saccular dilation our outpouching of the mucosa through the circular smooth muscle of the intestinal wall. Occurs in two forms: diverticulosis and diverticulitis. 9 Diverticulosis-develops in about 50% of persons over age 60. Occurs when there is multiple diverticula without inflammation or symptoms. Patient usually asymptomatic. Diverticulitis-Condition involving inflammation of the diverticula. Occurs when food or bacteria becomes trapped in the diverticula. Change in bowel habits, dull pain in the abdominal LLQ or the epigastrium, rectal bleeding, anorexia, low-grade fever, constipation, flatulence. The sigmoid colon is the most common site for diverticulitis. Stools may be narrow (remember, those sacs can distort!). From increased intraluminal pressure (decreased bulk of the stool, more narrowed lumen) from factors such as a low-fiber diet, chronic constipation, and obesity. Complications of diverticular diseaseAcute-hemorrhage, perforation, periodic abscess, general peritonitis, local suppuration, fistula. Chronic-pericolic abscess, stricture, fistula, local suppuration, intestinal obstruction, perforation, etc. BLEEDING-A common complication. Manifested by hematochezia (maroon stools). Usually stops spontaneously. Tests CBC (↑ WBC level and elevated sed rate) Colonoscopy Barium enema A tender, LLQ mass may be palpated. Treatment High-fiber diet and bulk laxatives (Metamucil?) Anticholinergic drugs (Bentyl, Donnatal). Increased fluids Reduction in weight, if obese. No tight clothing, straining during BM, bending, lifting, vomiting ALLOW THE COLON TO REST so inflammation can subside. NPO, bed rest, parenteral fluids; maybe NG tube. If acute, broad-spectrum antibiotics. May need temporary diversional colostomy. No foods with little seeds (popcorn, strawberries, etc) Hiatal Hernia It is a herniation of a portion of the stomach into the esophagus through an opening, or hiatus, in the diaphragm. Also referred to as diaphragmatic hernia and esophageal hernia. Occur more often in women than in men! Exact cause unknown. 10 Types Sliding-The junction of the stomach and esophagus is above the hiatus of the diaphragm, and a part of the stomach slides through the hiatal opening in the diaphragm. The stomach “slides” into the thoracic cavity when the patient is supine and usually goes back into the abdominal cavity when the patient is standing up. This is the most common type. Paraesophageal or Rolling-The esophagogastric junction remains in the normal position, but the fundas and the greater curvature of the stomach roll up through the diaphragm, forming a pocket alongside the esophagus. What causes it? Signs of it? Exact cause is unknown. Structural changes may contribute: Weakening of the muscles in the diaphragm around the esophagogastric opening. Obesity, pregnancy, ascites, tumors, tight corsets, intense physical exertion, heavy lifting on a continual basis. (Weightlifters, Beware!) Also, increasing age, trauma, poor nutrition, forced recumbent position (when prolonged illness keeps a person in bed) Persons may be asymptomatic. Symptoms may be a lot like GERD. Heartburn is a classic symptom. Symptoms may also mimic gallbladder disease, PUD, and angina. Reflux often associated with position, occurring soon or several hours after laying down. Bending over may cause a severe burning pain. Complications: GERD Hemorrhage from erosion. Stenosis (narrowing of the esophagus) Ulcerations of the herniated portion of the stomach. Strangulation of the hernia Regurgitation with tracheal aspiration. Patients with hiatal hernias are more at risk for hospitalization for respiratory disease! Diagnosis Barium swallow Endoscopic visualization Monitoring of pH. Motility studies Fluoroscopy, X-rays Treatment- 11 Conservative therapy similar to that of GERD. Reduction of intraabdominal pressure by eliminating constricting garments, avoiding lifting and straining, eliminating alcohol and smoking, elevating the head of the bed. The use of antacids and antisecretory agents (PPIs and H2R blockers) Don’t want to use anticholinergics because they relax the esophageal sphincter. Elevate the head of the bed on 4- to 6- inch blocks to assist gravity (prevent reflux and tracheal aspiration.) Eliminate caffeine-containing beverages and chocolate. Surgical Therapy Nissen fundoplication Toupet fundoplication Hill gastropexy Belsey fundoplication. These procedures are all variations of fundiplication which involves wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the lower portion of the esophagus in varying positions. These procedures reduce the hernia, provide and acceptable LES pressure, and prevent movement of the gastroesophageal junction. Usually laparoscopic. May also be done thoracic or open abdominal. Cholecystitis and Cholelithiasis Cholecystitis-Acute or chronic inflammation of the gallbladder. Acute may be calculous (with gallstones) or acalculous (without gallstones). Most common in middle- 12 aged people. Greater in women than men. Chronic may follow acute. Usually associated with gallstone formation. The chronic form usually affects the elderly. Still greater in women. Can occur from trauma, extensive burns, or recent surgery. Can also occur from prolonged immobility and fasting. Bacteria can also cause it (Esherichia coli). Also, adhesions, neoplasms, anesthesia, and narcotics. Cholelithiasis-Refers to formation of calculi (gallstones) in the gallbladder. Associated with about 90% of gallbladder disease in the U.S. Incidence greater in women than men before age 50. After that, about equal. Occurs when the balance that keeps cholesterol, bile salts, and calcium in solution is altered so that precipitation of these substances occur. The bile is usually supersaturated with cholesterol (lithogenic bile). The same thing happens to the bile in the gallbladder. Other components of bile that precipitate into stones are bile salts, bilirubin, calcium, and protein. Clinical Manisfestations Obstructive jaundice Dark amber urine that foams when shaken. No urobilinogen in urine. Clay-colored stools Pruritis (itch, itch, itch) Intolerance for fatty foods (Nausea, feeling full, anorexia) Bleeding tendencies Steatorrhea Etiology No bile flow into duodenum. Soluble bilirubin in urine No bilirubin reaching the small intestine to be converted to urobilinogen. Same as above! Deposition of bile salts in skin tissues. No bile in small intestine for fat digestion. Lack of or ↓ absorption of vitamin K, resulting in ↓ production of prothrombin. No bile salts in duodenum, preventing fat emulsion and digestion. Pain is usually in RUQ but can radiate to mid-upper back. Jaundice indicates that stone(s) is in common bile duct. Bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase may increase. Pain must be differentiated from the pain caused by other disorders like pancreatitis, MI, or kidney. Diagnosis Cholangiography or radioactive scan. Oral cholecystogram (may outline stones) Endoscopic or percutaneous cholangiography. Must be NPO Treatment Laparoscopic cholecystectomy preferred treatment. Also, Incisional Cholecystectomy. Drugs that dissolve the stones. Bile acid chemodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) can completely or partially dissolve. 13 Patient may need vitamin K if Prothrombin levels are low or if patient is jaundiced. T-Tube to drain bile while duct is edematous. Record amount, color, consistency; report any sudden change in drainage (may mean edema or spasm), skin integrity. Empty bag as needed. IV fluid NPO with NG tube, later progressing to low-fat diet Antiemetics Analgesics Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) Anticholinergics (Antispasmodics) Antibiotics (for secondary infection) ERCP with sphincterotomy (papillotomy) Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy Dissolution therapy-Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), Ursodiol (Actigall), Chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) COLON Cancer Third most common kind of cancer in the U.S. Most prevalent over the age of 50. In both sexes, the incidence of right colon cancers has increased and cancers in the rectum have decreased. Most often seen in the rectum, ascending colon, and sigmoid colon. Tumors in small intestine are rare. Arises from epithelial lining. 14 Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of colon cancer. All colorectal cancers appear to arise from adenomatous polyps. Spread through the walls of the intestine and into the lymphatic system. Spread to the liver because the venous blood flow from the colorectal tumor is through the portal vein. Clinical Manisfestations: Depends on Where the Lesion Is! Cancer on the right side of the colon gives rise to clinical manisfestations that are different from those on the left side of the colon. Rectal bleeding, the most common symptom of colorectal cancer, is most often seen with left-sided lesions. Also on the left side-Alternating constipation and diarrhea, change in stool caliber (narrow, ribbonlike) and sensation of incomplete evacuation. Obstruction symptoms appear earlier with left-sided lesions because of the smaller lumen size. Cancers of the right side are usually asymptomatic. Vague abdominal discomfort or crampy, colicky abdominal pain. Iron deficiency anemia and occult bleeding indicate further investigation. See weakness and fatigue. Risk Factors: Age >50 years Familial polyposis Colorectal polyps Chronic IBD Family Hx of colorectal cancer or adenomas Previous Hx of colorectal cancer History of ovarian or breast cancer High-fat and/or low-fiber diet (controversial) S & S: Transverse colon: Pain, obstruction, change in bowel habits, anemia. Ascending colon: Pain, mass, change in bowel habits, anemia. Descending colon: Pain, change in bowel habits, bright red blood in stool, obstruction. Rectum: Blood in stool, change in bowel habits, rectal discomfort. [Pain, abdominal or rectal. Tenesmus, anal spasms, Feeling bloated even after BM, Unexplained weight loss! Sudden obstruction, heme in stools, anemia, fatigue, narrowing with stools.] Diagnose: Digital rectal exam Fecal occult blood testing Sigmoidoscopy Double-contrast barium enema Colonoscopy Endorectal ultrasonography 15 CT scan (before surgery) Elevated CEA and alpha fetoprotein (CEA does not exclude the possibility of a malignant condition. Elevated or increasing CEA levels suggest residual tumor or tumor spread. DCC gene products expressed as tumor antigens CO17-1A glycoprotein expressed by colorectal cancer. TreatmentSurgical Therapy-The only curative treatment of colorectal cancer. Right hemicolectomy-Performed when the cancer is located in the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, or transverse colon to the right of the middle colic artery. A portion of the terminal ileum, the ileocecal valve, and the appendix are removed and an ileotransverse anastomosis is performed. Left hemicolectomy-Resection of the left transverse colon, the splenic flexure, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, and the upper portion of the rectum. Abdominal-Perineal Resection-Performed when the cancer is located within 5 cm of the anus. Abdominal incision made; proximal sigmoid brought through the abdominal wal lin a permanent colostomy. The distal sigmoid, rectum, and anus are removed through a perineal incision. Low-Interior Resection-May be indicated for tumors of the rectosigmoid and the mid-to-upper rectum. The use of EEA (end-to-end anastomosis) staplers has allowed lower and more secure anastomoses. Chemotherapy-When the patient has positive lymph nodes at the time of surgery or has metastatic disease. Combination of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) plus leucovorin and irinotecan (Camptosar)-1st line chemo for patients with metastatic colorectal cancers. 5-FU and levamisole (Ergamisol) with or without leucovorin (Wellcovorin) Also oxaliplatin (Eloxatin), raltitrexed (Tomudex), and monoclonal antiobodies. Radiation-May be used postoperatively as an adjuvant to colon resection and chemo or as a palliative measure. (Reduce tumor size and provide symptomatic relief.) Care Some NSAIDS or long-term use of aspirin may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer. Teach side-to-side positioning (Post-op) Drainage for surgical wound-Usually serosanguineous. Observe for signs of edema, erythema, drainage around suture line, fever, elevated WBCs. Moist heat for vasodilation. Not too much though; May cause TOO much vasodilation. 16