the good mother

advertisement

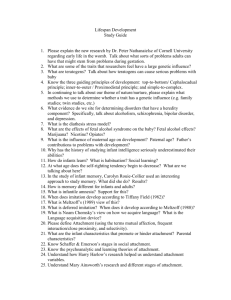

The Good-Enough Running Head: The Good-Enough Critical Development The Good-Enough Mother: After Effects Colette Spear 200834518 University of Johannesburg 1 The Good-Enough Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………….…… 3 Background …………………………………………………………………… 3 The Psychoanalytic Perspective…………………………………………… 3 Erikson’s Psychosocial Stage Theory …………………………………….. 3 Piaget’s Cognitive Stage Theory …………………………………………. 3 Attachment Theory ……………………………………………………….. 4 The Object-Relations Theory…………………………………………………. 4 Separation Individuation Process: Stages…………………………………….. 4 Donald Winnicott: The Role of the Mother…………………………………... 6 The Developmental Process………………………………………….……. 6 Subjective omnipotence (Me)…………………………………..……… 6 Object Reality (Not-Me/Other-Than-Me)……………………………... 7 The Final Stage: Independence……………………………………….. 8 Transitional Experience and the Transition Object………………………... 8 The Holding Environment (Facilitating Environment)……………………. 8 Qualities and Effects of The Good-Enough Mother…………………………… 9 The True Self and the False Self………………………………………………. 10 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………….. 11 References…………………………………………………………………….. 12 2 The Good-Enough 3 Introduction The idea of a “good-enough mother” was developed by Donald Winnicott, an object-relations theorist in the mid 1900’s. Object-relations theorists focus on the individual’s relationship with the mother, and the significant effects that the quality of this relationship has on a child’s future relationships. Unlike the attachment theorists, Winnicott (1971) highlighted the importance of the transition between stages of development, and the role of the mother (the object) in the child’s transitional experience. The infants relations with objects of love shape future relationships, and the development of the child’s self, as a unique and creative individual. (Frude, 1998; Maddi, 1996; Winnicott, 1971) Background The Early Psychoanalytic Theory Freud maintained that the reason an infant develops an attachment with the mother is because she instantly gratifies the needs of the child’s id, for example, feeding the infant when the infant is hungry. This relationship between infant and object is, therefore, a narcissistic attachment. Simply put, the mother is a source of food and warmth, and nothing more. The assumption is that the id’s needs are pre-programmed and exist automatically, therefore, the attachment with the mother is none other than a programmed attachment, devoid of love. The quality of interpersonal interactions, therefore, has no influence on future relationships with others. (Maddi, 1996; Wenar & Kerig, 2005) Erikson’s Psychosocial Stage Theory Erikson divides the course of an individual’s social growth through life into eight developmental stages, each stage a progression from the one before. During each of the stages the individual has to overcome a ‘psychosocial crisis’. The psychosocial crisis has a push-pull effect on the person as two opposing tendencies, for example, trust versus mistrust, exist within the person. Once the person has overcome the crisis between traits, he or she can move on to the next stage. (Weiten, 2001) Piaget’s Cognitive Stage Theory Piaget posited that the interaction of cognition and the child’s level of maturation, result in a specific form of thinking. His theory presents four stages of cognition, from birth to The Good-Enough 4 adulthood: i) sensorimotor period; ii) preoperational period; iii) concrete operational period, and; iv) formal operational period. (Weiten, 2001) The Attachment Theory The attachment theorists built upon the theories of Piaget, Erikson, and Freud. The attachment theorists suggest that close bonds (attachments) develop between the baby and the caregiver, and that the quality of these bonds has an lasting effect on the child’s future attachments with others. Research by attachment theorists such as Ainsworth and Bowlby produced evidence of different patterns of attachment between caregiver and child and the resulting effects of each pattern. Emphasis is placed on the quality of initial attachments formed in the early years of development. The Object-Relations Theory In a move away from Freud’s focus on the id, the object-relations theorists emphasize the tendency to develop a self, in conjunction with significant interpersonal relationships, as the basis upon which the self is developed. The ‘object’, in object relations theory, refers to a person other than oneself (Reber, 1995). The child’s sense of self is defined by the relationships the child has with objects of his, or her, love and affection (initially the mother or caregiver). The ‘object’, in object relations theory, refers to a person other than oneself (Reber, 1995). The quality of attachments with objects has a critical, and determining, impact, not only on the development of the self, but also on the child’s future relationships with others. (Maddi, 1996) The child derives his or her self worth and trustworthiness from the messages communicated by the caregiver. The primary motivating force in human behaviour, including development of relationships, is love (Reber, 1995). The emotional bonds between oneself and another (an object) are a balance between love and affection for another, and interest in, and love for, the self. A person will, therefore, invest love and affection into a relationship with another, whilst ensuring his or her independence, self worth, and love for the ‘self’, remains in tact. (Maddi, 1996; Wenar & Kerig, 2005) Separation Individuation Process: Stages Object-relations theorist, Margaret Mahler (1963), describes the process whereby a child develops a relationship with another (an object), over the first three years of life, as the The Good-Enough 5 separation individuation process. For the first few weeks after birth a phase of normal autism occurs during which the infant perceives the mother as ‘one with the self’. The relationship with the mother as the object is, as Freud proposed, based upon the fulfillment of the infant’s basic needs. If these needs are attended to without delay by the caregiver, the child will progress to the symbiotic phase. This phase is one of confusion for the baby, as a result of the realization that the mother is not one with the self, but rather the self and the mother are perceived as two parts of one organism. (Maddi, 1996; Wenar & Kerig, 2005) The differentiation phase occurs at approximately four months, and the child recognizes others as separate from the self. At approximately eight months the child begins to crawl, thereby allowing for exploration of the environment. During this phase (the practicing phase) it is essential that the child is able to return to the mother as a safe base. The following phase, the rapproachment phase, occurs at about the age of two years. In line with Piaget’s ‘pre-operational stage’, symbolic thought gives rise to thoughts of vulnerability. The child craves independence, however, thoughts about the possible consequences, such as getting lost, may hinder this progress. This results in an ambivalent attachment with the caregiver. (Maddi, 1996; Wenar & Kerig, 2005) Emotional object constancy is the final phase in the object relations development process. The optimally healthy child is able to understand that the love and trust between the object and the self remains constant, regardless of current feelings of anger or pain. (Maddi, 1996; Wenar & Kerig, 2005). Child Mother Normal Autism Child Mother Symbiotic Child Mother Differentiation; Practicing; Raproachment; and Emotional constancy Figure 1.1 Margaret Mahler’s separation individuation process: stages The Good-Enough 6 Donald Winnicott: The Role of the Mother Donald Winnicott took the stages of separation individuation to another level. In line with Margaret Mahler’s process of separation individuation, Winnicott studied the role of the mother (caregiver) in the child’s social development. He emphasized the importance of the mother’s ability to intuitively understand the infant’s needs at each point throughout the process of individuation. By reading the child’s subtle messages and cues, the mother is able to provide the framework for the child’s progress towards an optimal level of functioning as an individual. A mother who provides a facilitating (holding) environment within which her child can grow is, as Winnicott defines, “a good-enough mother”. He chose not to use the term ‘perfect’ in his definition of a good mother, as only a machine is able to produce perfection, not a human. For Winnicott, a perfect mother is actually a ‘not-good’ enough mother. (Winnicott, 1971) The Developmental Process Winnicott describes three major stages of development, the stage of subjective omnipotence, the stage of objective reality, and the final stage of independence. The zone between the stages is, for the child, a transitional experience and it is at this point that a ‘good-enough mother’ is most crucial. The quality of the transitional determines the child’s future functioning, or lack thereof. For Winnicott, the mother plays an important role in both the stages of development, and the transitional experience. Subjective omnipotence (Me) Initially, when a mother has her baby, she attends to her babies every need with complete indulgence, responding immediately when her baby cries. This is referred to as a state of maternal preoccupation. During this time the mother puts aside her own needs in order to ensure that the needs of her infant are met. The moment her infant cries for food she produces her breast. As a result of this state, the infant develops the illusion that the mere wish for food causes the immediate appearance of a breast. This illusion of magical control is an experience of subjective omnipotence. (Winnicott, 1971; Rodman, 2003) Winnicott theorises that the mother’s breast is the object of love during the first few weeks after birth, as it is the breast that fulfills the infant’s primary basic need for food during this phase of normal autism. During this phase the infant perceives the object as part of the The Good-Enough 7 self, therefore, the infant develops a subjective phenomenon with the illusion that the breast is part of the infant’s self. The illusion of being-at-one with the object is the first step in the infant’s development of an identity. This point highlights the essential role of the goodenough mother and the possible devastating effects of the ‘not-good-enough mother’ in the child’s developmental process. (Winnicott, 1971) Object Reality (Not-Me/Other-Than-Me) The good-enough mother begins to distance herself from her child in response to her child’s growing need for independence. The good-enough mother first provided the child with an illusion that a breast appears on demand (omnipotence). Then she creates the disillusion (removal of omnipotent thinking) that progressively introduces the child into the social world as a separate being. (Winnicott, 1971) The mother allows for increasing time lapses between the child’s demands for attention or need gratification and her responses. Winnicott (1971) refers to this as the mother’s ‘failure’ to attend to the child immediately. The child experiences both frustration at having to wait and a new found freedom within which to grow. The good-enough mother will only ‘fail’ her child at a rate that the child is able to deal with. (Rodman, 2003; Winnicot, 1971). In order to cope with the mother’s failure and the resulting frustration, the child will: Recognise that the time lapses are limited Become aware of a sense of progress Develop mental activities which assists in deterring the child during times of frustration Indulge in auto-erotic stimulation, for example thumb sucking Experience memories, fantasies, dreams, and reliving previous experiences, that is, the integration of the past, present, and future. (Winnicott, 1971, p 14) An awareness of the mother as an object separate from the self begins to form. The baby starts to realise that, not only is there is a world outside of the self which does not respond to a wish (the dissolution of the subjective omnipotence), but also that the object of reality (outside world) sometimes responds negatively. The good-enough mother ensures that the child feels safe without being overprotective. (Winnicott, 1971; Stovall-Mcclough, K. C. & Dozier, M., 2004). The Good-Enough 8 If the mother fails to assist her child to transcend from this stage to near-independence as an adult, the child will be superficially adjusted as an adult and not unique and passionate. The good-enough mother gently distances herself from her child in order to allow the child the freedom to experience and learn, whilst still providing a facilitating (holding) environment so that the child feels safe and secure. (Rodman, 2003) The Final Stage: Independence The ‘never absolute’ phase of independence is the final phase of development. Winnicott makes the important distinction between pure independence and ‘never absolute’ independence in the sense that throughout an individual’s life it is necessary to both depend on others and be depended on by others. A psychologically healthy person seeks the company of others and the need to feel as though he or she belongs. Isolation is not conducive to a healthy psyche, however, neither is an overdependence on others. Transitional Experience and the Transition Object The transcendence from the phase of subjective omnipotence to objective reality is called the transitional experience, and is an intermediate state or zone in which the mother plays an important role. Due to the increasing distance between the child and the mother, the child may become anxious and fearful. A transitional object helps the child through the transitional experience, acting as a psychological bridge, as the child transcends from the safety of having an ever present mother to the freedom of becoming an individual. The transition object is a comforter and may take the form of a blanket, a teddy bear, or any other object that acts as a connection to the mother, and a defense mechanism for the fear and anxiety experienced during the mother’s absence. The transition object is not a replacement for the mother, but rather a representation of the mother during her absence. (Landzelius, 2003; Maddi, 1996; Rodman, 2003; Winnicott, 1971) The Holding Environment (Facilitating Environment) The mother is responsible for creating a safe environment within which the baby can experience the outside world. Winnikot referred to this ideal therapeutic environment as the holding environment or facilitating environment. This place adjusts in accordance with the child’s developmental needs. The Good-Enough 9 As the child develops into an individual, separating from the mother, the holding environment becomes a safe haven for the child to explore the outside world, knowing that the mother is still providing the much needed safety and protection. This continuity of care is essential in the holding environment for a child’s healthy development. The good-enough mother follows her child’s cues, intuitively understanding what her child needs are with respect to the holding environment, and she adapts the environment accordingly. (Winnicot 1971; Rodman, 2003) Child Object Transitional Experience Subjective Omnipotence (me) Child Object Transitional Experience Objective Reality (not-me) Child Object Individual Figure 1.1 The holding environment Qualities and After Effects of the Good-Enough Mother The good-enough mother provides a facilitating environment wherein the infant can develop from birth to adulthood. The optimal environment facilitates this process in the sense that the good-enough mother is intuitively in tune with her baby’s developmental needs, adapting both the environment, and her role in her child’s growth, at a rate determined by her child. In the first phase, the good-enough mother attends with immediacy to her child’s basic needs, providing food and warmth on demand. The holding environment created and maintained by the mother at this point in the child’s development, is one where the child is held, handled, and presented with objects, for example, her breast (Winnicott, 1971). The good-enough mother provides the child with the illusion of omnipotence and protection from frustration and anxiety. Within this environment the child is able to develop to a point where he, or she, feels safe to begin the experience of transcendence to the next stage of development. If, however, the mother is a ‘not-good-enough mother’, the child may develop a psychosis in later life. The Good-Enough 10 The not-good-enough mother either does not attend to her infant’s primary needs within the time-frame that is expected by the infant, or she may be a ‘perfect-mother’, continuing to supply on demand past the point that the child is ready to transcend this stage, thereby not adapting to her child’s changing needs. (Rodman, 2003) The good-enough mother knows how to gradually adjust increase the distance between herself and her child. This process of differentiation cannot be sudden for the child will become insecure and untrusting if his, or her, feeling of control is shattered. The goodenough mother is finely tuned to her child’s progression towards an independent self, moving at the child’s pace and not at her own. If all goes well, the child’s ego develops and the process of differentiation continues until the child is able to perceive, with clarity, the mother as a separate being. Omnipotence is replaced by reality, and a psychologically and socially healthy, independent, autonomous, individual is created. (Rodman, 2003) Winnicott suggested that the ‘not good-enough mother’ in some cases hates her child. The child develops a pattern of insecure attachment and a fear of abandonment. Winnicott emphasized the importance of a “safe space” to be provided by the therapist, within which the child can work through this insecurity and fear. (De Mause, 2006). The True Self and the False Self The true self and the false self exist on a continuum, with the healthy true self and the healthy false self on the one side, and the pathological false self on the other. Within every infant a true self exists. The true self is the self that behaves spontaneously, is built on integrity, and exists, that is, the true self is not created. The good-mother facilitates the growth and expression of the child’s true self by allowing the child to be creative and spontaneous. (Rodman, 2003) healthy true self healthy false self…………………………………………unhealthy false self Figure 1.2 True self and false self The false self is a mask which an individual wears when complying with the social norms of society, such as being quiet in settings that call for silence, and being polite and The Good-Enough 11 respectful in other settings. The not-good-enough mother wears this mask when interacting with her child and her child, in response to the unnaturalness and unauthentic relationship with the mother, develops his or her own false self. The child continues to develop new relationships as the false self, adapting to the demands of the environment with compliance. (Rodman, 2003) An individual who, on average, behaves in accordance with the true self, feels real and true to himself, or herself, resulting in future authentic relationships. A healthy, alive, and happy individual will still wear the mask of the false self when the situation demands, however, the individual will continue to be true to himself, or herself, during this time. An individual who, when wearing the false mask, continues to be false to himself or herself feels a sense of unreality, of not being alive and happy. (Rodman, 2003) Conclusion Theories of attachment associate the quality of early parental styles with the child’s future relationships with others, predicting that these adults will develop as secure or insecure adults. A third category has been identified, that of “earned” security, that is, through intervention the child is able to overcome the effects of early negative attachments. Children who initially have unhealthy relationship experiences are not, therefore, destined to have failed future relationships if they have earned security. As adults, with earned security, they may well become good-enough mothers. Winnicott acknowledges the fact that a caregiver, other than the mother, can play the role of the good-enough mother in the life of a child. However, he maintains that the biological mother instinctively bonds with her baby at a level which is unobtainable by another caregiver. At the core of his theory, the good-enough mother is one who intuitively knows her child’s every nuance, and is, therefore, able to detect her child’s changing needs. The good-enough mother provides for these needs within the framework of the facilitating environment. As such, the child is allowed the opportunity to develop a healthy sense of self worth and trustworthiness as he, or she, develops into a psychologically healthy, autonomous, individual. The Good-Enough 12 References Aviezer, O., Sagi, A., & van Ijzendoorn, M. (2002). Balancing the family and the collective in raising children: Why communal sleeping in Kibbutzim was predestined to end. Family Process, 41(3), 435-54. Retrieved July 24, 2008, from ProQuest Psychology Journals database. (Document ID: 222592911). Edwards, M. E. (2002). Attachment, mastery, and interdependence: A model of parenting processes. Family Process, 41(3), 389-404. Retrieved July 24, 2008, from ProQuest Psychology Journals database. (Document ID: 222585981). Martin, Betty Marie (2005) Using projective measures to examine the relationship between adult attachment status and object relations. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Tennessee, United States -- Tennessee. Retrieved July 31, 2008, from ProQuest Psychology Journals database. (Publication No. AAT 3193602). Lloyd deMause (2006). Donald Winnicott and John Bowlby: Personal and Professional Perspectives. The Journal of Psychohistory, 33(4), 402. Retrieved July 31, 2008, from ProQuest Psychology Journals database. (Document ID: 1015105521). Frude, N. (1998). Understanding abnormal psychology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Landelius, K. M. (2003). Humanizing the impostor: Object relations and illness equations in the neonatal intensive care unit. Clture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 27(1-28). Retrieved July 30, 2008, from ProQuest Psychology Journals database. Mayer, S. F. & Sutton, K. (1996). Personality: An integrative approach. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc Priel, B. & Besser, A. (2001). Bridging the gap between attachment and object relations theories: A study of the transition to motherhood. British Journal of Medical Psychology,1 74, 85-100. Retrieved July 24, 2008, from ProQuest Psychology Journals database. (Document ID: 72018437). The Good-Enough 13 Prosada, G. & Pratt, D. M. (2008). Physical aggression in the family and preschoolers’ use of the mother as a secure base. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 34(1), 1427. Retrieved July 24, 2008, from ProQuest Psychology Journals database. (Document ID: 1426041211). Rodman, F. R. (2003). Biography: Winnicott: Life and work. Cambridge: Perseus Books. Stovall-Mcclough, K. C. & Dozier, M. (2004). Forming attachments in foster care: Infant attachment behaviors during the first 2 months of placement. Development and Psychopathology, 16(2), 253. Retrieved July 24, 2008, from ProQuest Psychology Journals database. (Document ID: 726645021). Weiten, W. (2001). Psychology themes and variations (5th Ed). USA: Wadsworth, Thompson Learning, Inc. Wenar, C. & Kerig, P. (XXX). Developmental psychopathology: From infancy through adolescence (5th Ed). McGraw Hill International Edition Winnicott, D. (1971). Playing and reality. England: Penguin Books