Film Curriculum 2007 Update

advertisement

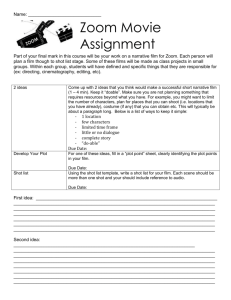

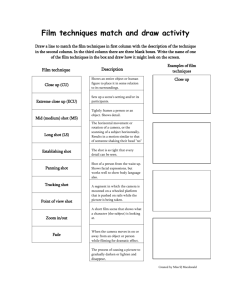

Film Curriculum 2007 Update General Course Objectives/Rationale: The purpose of this course is to examine how film/television has grown into the predominant storytelling medium of today. We will trace the ancestry of film through books, plays, art, comic strips, and graphic novels to learn the traditional ways that mankind has captured and interpreted fiction and history to portray the human experience. Moreover, we will be examining the tools, techniques and practices of writers, directors, editors, actors and even the audience use to bring forth life from a celluloid image. State Standards 1.1 Learning to read independently 1.2 Reading critically in all content areas 1.3 Reading, analyzing and interpreting literature 1.4 Types of writing 1.5 Quality of writing 1.6 Speaking and listening Unit 1- Film Fundamentals Content Manos: Hands of Fate (Mystery Science Theatre 3000) “Nightmare at 30,000 Feet”-short story by Richard Matheson (Packet) Nightmare at 30,000 Feet, Twilight Zone (Tv. 1963) and/or (film 1984) Spider-man (2002) Dir. Sam Raimi PG-13 Film review a. Introduction and Purpose of Unit/Objectives 1. The purpose of this unit is to introduce the most common tools of a film maker 2. Independently analyze a film review for its effectiveness a piece of persuasive writing as defined by the PSSA persuasive scoring rubric 3. Review of all camera angles and special effects as story telling tools, especially perspective shots. Assessment Objective test on terminology with essays analyzing specific use in the films showed in class. Unit 2 Adaptations Content Dracula - Bram Stoker excerpts from novel Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) film Dr. F.F. Coppola “Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption” (Novella from King’s Different Seasons) Shawshank Redemption 1994 Dr. F. Darabont Wizard of Oz- Novel L. Frank Baum (excerpts) Wizard of Oz- Film 1939 Dir. Victor Fleming G Gone with the Wind- Margaret Mitchell (excerpts) Gone with the Wind- Film (1939) Dir. Victor Fleming G The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis (excerpts) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005) Dir. Andrew Adamson PG Assessment 1. Objective quiz/test on the important background information for each film 1. Independent assignment-read a novel independently and present film version segments with important connections and discuss director/screenwriter use of artistic license to bring the work to the screen. Unit 3 Re-imaginings/Conceptualizations Purpose/Objectives 1. Analyze more fully director/screenwriter use of artistic license to bring the elements of a particular work to the screen. Content Scrubs 100th episode season 5 (Wizard of Oz reinterpretation) 2005 Novel Emma by Jane Austen (excerpts) Clueless 1995 Dir. Amy Heckerling PG-13 Macbeth (excerpts) Scotland, Pa (Macbeth reinterpretation) 2001 Dir. Billy Morrissette R (appropriate clips) Taming of the Shrew (excerpts) 10 Things I Hate About You (Taming reinterpretation) 1999 Dir.Gil Junger PG-13 Selected stories from 9 Stories by J.D. Salinger Royal Tannenbaums dr. Wes Anderson 2001 R (appropriate clips) Assessment Essay- Focus on one of the re-imaginings and discuss how it was faithful to its source material while still presenting its own life as an artistic product. Cite specific differences and outline how they effect the reception of the work. Thematic: Coming of Age/ Initiation Purpose/Objectives 1. Analyze the techniques used in coming of age stories in both literature and film. 2. Cite classic coming of age novels as background for the comparisons including Huckleberry Finn 3. Analyze the role of parent figures/role models in each film, especially in A Bronx Tale, and the lack of these figures in the other films. 4. Compare the Novella the body with its film version Stand By Me 5. Compare the differences in social expectations between males and females especially in Virgin Suicides. Content Novella- The Body by Stephen King Bronx Tale Stand By Me Virgin Suicides Assessment Compose an essay outlining defining moments in the transition to adulthood in each film. Compare the plight of the protagonists with each other and those of classic literature citing specific. Also explore the importance of role models in this transition. Thematic: Power of Individual Purpose/Objectives 1. Explore the common literary theme of one man versus society and how an individual can function as catalyst for change. 2. Explore historical figures that have made a tangible impact on the world. Content Chocolate War Literature Connection: The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier Erin Brockovich Dead Poets Society (1989) Dir. Peter Weir PG Mona Lisa Smile (2003) Dir. Mike Newell PG-13 Cool Hand Luke Shawshank Redemption Angus (1995) Dir. Patrick Read Johnson PG-13 Literature Connection: “A Brief Moment in the Life of Angus Bethune” by Chris Crutcher (short story). Assessment Essay topic- Provide an example of someone in “real life” (past or present) who changed the world for the better. What qualities does this person have that are similar to the qualities of one of the characters in this film unit? Thematic: Conformity Text: Queen Bees and Wannabes by Rosalind Wiseman Mean Girls (2004) Dir. Mark Waters PG-13 Swing Kids (1993) Dir. Thomas Carter PG-13 Graduate (1967) Dir. Mike Nichols PG (novel by Charles Webb) Garden State (2004) Dir. Zach Braff R Saved! (2004) Dir. Brian Dannelly PG-13 The Breakfast Club (1985) Dir. John Hughes R Assessment Essay topic-As a teenager, discuss the role pressure to conform to the societal “norm” shapes one’s character. Cite specific examples of characters in the films that broke the barriers of conformity and explore how they did so. Thematic: Archetypes /Fate vs. Free Will Purpose/Objectives 1. Analyze the mythological foundations of literature and film. 2. Examine common archetypes of the hero, villain, sage and commoner as seen in literature and film via Star Wars, History Channel documentary SW Legacy Revealed 3. Examine the struggle of characters against seemingly inescapable fate in both mythological and modern settings 4. Examine use of design and special effects to heighten otherworldly/mythological elements of Star Wars films. 5. Discuss George Lucas’s film influences, including Kurasawa and the 1940’s Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon serials . Resources Joseph Campbell- Hero of a Thousand Faces, Power of Myth, or various articles on mythological Archetypes Star Wars Films Episodes III-VI Star Wars the Legacy Revealed History Channel Documentary Stranger than Fiction 2006 Dir. Marc Forster PG-13 The Princess Bride (1987) Rob Reiner PG Segments from Kurasawa’s Hidden Fortress (Optional) Batman Begins (2005) Dir. Christopher Nolan PG-13 Assessment 1. Write an essay on other major films that utilize archetypes in their own way, such as The Lord of The Rings Trilogy, The Matrix Trilogy, The Princess Bride, Excalibur, or other works of Arthurian Legend, fantasy etc. 2. Write an essay on other major films that utilize the struggle of fate versus free will in their own way, such as The Lord of The Rings Trilogy, The Matrix Trilogy, Excalibur, Donnie Darko or other appropriate films. 3. Write an essay defining the impact of George Lucas and his films on modern directors and films in terms of story, directing, special effects and marketing. Thematic Unit: Positions of Power Purpose/Objectives 1. Read segments of Il Principo (The Prince) by Niccolo Machiavelli to understand its connection to the political/economical trappings of western government, dictatorships and organized crime. 2. Examine Coppola’s study of family structure versus criminal organization structure. 3. Compare the recommendations of Machiavelli with the actions taken by various members of the Corleone family. 4. Analyze the director’s use of music, camera work and symbolism to discuss why it is called the greatest film ever made. 5. Examine how leaders use public opinion to gauge their decision-making, and how a fickle public can bring about the downfall of leaders Resources: Machiavelli Il Principo- excerpt -Rules for leadership Princeton essay (http://www.princeton.edu/~ferguson/adw/prince.shtml) Godfather, Godfather II (optional) The Queen (2006) Dir. Stephen Frears PG-13 Marie Antoinette (2006) Dir. Sofia Coppola PG-13 Assessments 1. Essay- Discuss how Vito and Michael secure and maintain their position of authority as outlined in Machiavelli’s Prince. 2. Watch and review the Godfather trilogy and analyze how Coppola portrays themes such as corruption of innocence, the trappings of power, and passage of roles from fathers to sons. Hitchcock – Masterworks and Influences Purpose/Objectives 1. Outline Hitchcock’s position as the premier director of the early and mid twentieth century and the creator of the Suspense Thriller genre. 2. Discuss Hitchcock’s innovations in editing, cinematography, costuming, color scheme, and the role of director. 3. Examine film as a form of Voyeurism especially in Psycho and Rear Window 4. Explore themes and terms including: Macguffin, Spiral Shot, Vertigo Shot Possible misogyny etc. 5. Examine directors who have most closely followed in Hitchcock’s footsteps such as M. Night Shyamalan, David Fincher etc. Content North by Northwest Read Window Psycho Vertigo The Village (2003) Dir. M. Night Shyamalan PG-13 (optional additions/replacements) The Man Who Knew Too Much Dial M for Murder Rebecca Marnie Rope 39 Steps Sixth Sense (1999) Dir. M. Night Shyamalan PG-13 Unbreakable (2000) Dir. M. Night Shyamalan PG-13 The Others (2001) Dir. Alejandro Amenabar PG-13 Red Eye (2005) Dir. Wes Craven PG-13 Literature connection: “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson (short story to show author’s use of suspense) Assessment 1.Objective test 2. Specifically outline Hitchcock’s influence on later directors mentioned in the unit and find critical essays/reviews to solidify this point. Unit- Film as Text- Re-Imagining It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) Dir. Frank Capra G The Family Man (2000) Dir. Brett Ratner PG-13 (modernization of It’s a Wonderful Life) Foreign Films – Translating Truth Purpose/Objectives 1. The purpose of this unit is to broaden student awareness of other cultures. 2. Increase students’ ability to appreciate film as a universal art form will be enhanced though this unit. 3. Increase awareness of the important facets of the history and culture of other countries through imagery and dialogue. 4. Students will explore the effectiveness of satire and parody as seen in other cultures. Content Life Is Beautiful (1997) Roberto Begnini PG 13 Au Revior Les Enfantes (1987) Louis Malle PG Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) Guillermo Del Torro R Rashomon (1950) Akira Kurosawa PG 13 Spirited Away (2001) Hayao Miyazaki PG Assessment Essay prompt- Examine how each of the films were both emblematic of their individual culture and yet universal. Humor: Satire/Spoof Unit Purpose/Objectives 1. Understand the definition of satire and how it applies to both film and literature. 2. Explore the similarities and differences between satire and the “spoof” genre of film. 3. Distinguish between a “spoof” and a satire. Content Drop Dead Gorgeous (1999) Dir. Michael Patrick Jann PG-13 Best in Show (2000) Dir. Christopher Guest PG-13 Spaceballs (1987) Dir. Mel Brooks PG UHF (1989) Dir. Jay Levey PG-13 Literature connection: “A Modest Proposal”- Jonathan Swift Assessment: Which comedies were most effective at a broad-based level and which were most pointed toward at a specific audience? Also, which techniques (such as irony, exaggeration and satire) made these comedies effective? *Supplemental material may be added to each unit as long as the integrity of the unit is followed, and in the case of R-rated films, permission is obtained by department chair, curriculum coordinator, or administrator. The listed films are intended as options and not all may be covered as long as the objective of the unit is met successfully. New material is constantly being produced; therefore, the course is intended to evolve accordingly, in order to keep the course relevant. Student essays will be assessed by using the appropriate PSSA scoring rubric. Sun Valley High School Film as Literature Writing about Film And Glossary of Terms Materials gained before editing from http://www.dartmouth.edu/~writing/materials/student/humanities/film.shtml The Challenges of Writing About Film What's so hard about writing about film? After all, we all "know" movies. Most of us could recite the plot of Independence Day with greater ease than we could recite the Declaration of Independence. We know more about the characters who perished on Cameron's Titanic than we know about many of the people who inhabit our own lives. But it's precisely our familiarity with film that presents us with our greatest writing challenge. Film is so familiar and so prevalent in our lives that we are often lulled into passive viewing (at worst) or into simple entertainment (at best). As a result, certain aspects of a film are often "invisible." Caught up in the entertainment, we sometimes don't "see" the camera work, composition, editing, lighting, and sound. Nor do we "see" the production struggles that accompany every film - including the script's many rewrites, the drama of getting the project financed, the casting challenges, and so on. However, when your film professors ask you to write about film, it's precisely those "invisible" aspects that they want you to see. Pay attention to the way the camera moves. Note the composition (the light, shadow, and arrangement of things) within the frame. Think about how the film was edited. In short, consider the elements that make up the film. How do they function, separately and together? Also think about the film in the context when it was made, how, and by whom. In breaking down the film into its constituent parts, you'll be able to analyze what you see. As you analyze and write about film, remember that you aren't writing a review. Reviews are generally subjective: they explore an individual's response to a film and so do not require research, analysis, and so on. As a result, reviews are often both simplistic (thumbs up, thumbs down) and "clever" (employing the pundriven or sensational turns of phrase of popular magazines). While reviews can be useful and even entertaining pieces of prose, they generally don't qualify as "academic writing." We aren't saying that your individual and subjective responses to a film are useless. In fact, they can be most informative. Being terrified when you watch The Blair Witch Project can be the first step on the way to a strong analysis. Interrogate your terror. Why are you scared? What elements of the film contribute to your terror? How does the film play with the horror and documentary genres in order to evoke a fear that is fresh and convincing? And so on. Kinds of Film Papers Film Studies is a broad and fascinating field. The variety of its scholarship reflects that. Below are some of the kinds of papers you might be asked to write in a Film Studies course: Formal Analysis A formal analysis of a film or films requires that the viewer breaks the film down into its component parts and discusses how those parts contribute to the whole. Formal analysis can be understood as taking apart a tractor in a field: you lay out the parts, try to understand the function and purpose of each one, and then put the parts back together. In order to do a convincing formal analysis, you'll need to be familiar with certain key terms (outlined for you in the glossary). Returning to the tractor analogy: it's helpful to be able to understand and to use terms like "carburetor" when you take a tractor apart - especially if you hope to explain your process to an onlooker. Film History All films are deeply involved in history: they reflect history, influence history, have history. A film like Gone With the Wind not only tells a story of the South during the Civil War, but (more importantly) it reflects the values and ideas of the culture that produced it, and so can be understood as an historical document. All films are part of our culture's history. They derive from and contribute to historical events. War films, for example, take their substance from historical events. They also influence those events - by influencing wartime audiences to rally behind the troops, or to protest them. But films also have their own histories: 1. All films have production histories, which involve the details of how and why and when they were made. Production problems often (if not always) affect what we see on the screen. 2. All films have distribution and release histories: some films are released to different generations of audiences, to wildly different responses; other films are banned because they threaten certain cultural values. (Thailand, for example, banned both The King and I and the recent Anna and the King because, in the estimation of the Thais, the films were disrespectful to their royalty). 3. Finally, all films should be understood in the larger context of film history. A particular film might "make" history, through its innovations, or it might reflect certain historical trends. Ideological Papers Even films that are made to entertain promote some set of beliefs. Sometimes these beliefs are clearly political, even propagandistic: Eisenstein's Potempkin, for example, is a glorification of Soviet values. Other films are not overtly political, but they still promote certain values: Mary Poppins, for example, argues for the idea that fathers need to take a more active interest in their families. It's important to remember, when watching a film, that even films whose purpose it is to entertain may be promoting or even manipulating our feelings about a certain set of values. Independence Day, for example, is entertaining, in part, because it plays on our feelings of American superiority and "never say die." An analysis of the film benefits from a consideration of these values, and how they are presented in the film. Cultural Studies / National Cinemas Films reflect the cultures and nations in which they were produced. Hollywood films, one might argue, reflect certain things about our nation's culture: our love of distraction, our attraction to adrenaline and testosterone, our need for good to triumph over evil, and our belief that things work out in the end. Other cultures and nations have different values and so produce different sorts of films. Sometimes these films baffle us. We might watch a French film, for example, and wonder why it's funny. Or we might watch a Russian film and wonder why the director never calls for a close up. These observations are in fact excellent starting places. Consider differences. Find out if these differences reflect something about the national character, or if they reflect trends in the national cinema. You may find that you have something interesting to say. Discussion of the Auteur Auteur criticism understands a film as the product of a single person and his vision. In most cases, this person is the director. Auteur criticism is useful because it helps us to understand, for example, what makes a certain film a "Spielberg" film. However, auteur criticism is often based on the erroneous assumption that films are like novels - that is, that one person retains authorship and control. Film is a collaborative medium. It's important to understand that no one person can control the product. The Director of Photography, the screen writers (often many), the wardrobe and make-up people, the head of the studio - all these and others have a hand in determining the final product of film. Still, auteur criticism is widely practiced and is useful in helping us to understand the common themes and aesthetic decisions in films by the same director (or producer, or star). Keep in mind, however, that the best of the auteur criticism draws on other sources, like film history or formal analysis, in order to insure that the paper is not simply an examination of the private life or the psychology of the auteur. Prewriting Strategies Before you can write about a film you must, of course, view the film. Accordingly, the best prewriting strategy you can have is to be a careful and observant viewer. However, when viewing a film we don't always have time to study particular images and cameria techniques. This problem is less significant if we have access to videos, which permit us to review a scene again and again. Still, you'll sometimes be asked to write about a film that you'll see only once. How can you prepare yourself so that your observations will be sharp? What knowledge can you bring to a film that will inspire a thoughtful and focused analysis? The Elements of Composition Film is an incredibly complex medium. Just take a look at the credits at the end of any film. Each of the people listed there has contributed something essential to the film's production - from lighting, to sound, to wardrobe, to editing, to special effects. Because there's so much to talk about, you'll have to be selective if you want to write a good, focused essay. If you are a novice to writing about film, take the time to familiarize yourself with the film terms listed in the attached glossary. Knowing the terms sometimes helps you to see them on the screen. You'll begin to "see" the difference between a cutaway and a jump cut, or between a dissolve and a fade. Make sure you have a working understanding of how all the major components of film - writing, acting, lighting, composition, editing, sound, and so on - work together to create what you see on the screen. Then, when sitting down to watch a particular film, choose from among these many elements one or two that interest you. Is the editing particularly effective? Focus on that and don't struggle to take note of the lighting. Do you find the director's use of jump cuts innovative? Watch closely when these cuts occur. Perhaps the director has used jump cuts consistently whenever characters are engaged in intimate conversations. What is he trying to convey through this technique? If you are entirely unfamiliar with a film and aren't sure what you should be looking for, ask your professor. She should be able to point you to those scenes or techniques that deserve special attention. Annotating Shot Sequences Whenever you prepare to write a paper, you take notes. However, when analyzing a film, you may want to take a very particular sort of notes in which you annotate a shot sequence or scene. Annotating a scene involves labeling each shot in a sequence. For example, a scene may begin with an establishing shot, which segues into a dolly shot. The dolly shot comes to rest in a medium shot of the main character, who is looking off frame. Next comes a reverse angle subjective close-up shot, which dissolves into a montage. Labeling each of these shots - preferably using a system of abbreviations for efficiency's sake - enables you to keep track of the complex sequence of shots. When you review your annotations, you might see a pattern of camera movement and editing decisions (or, on the other hand, some unusual variation in the pattern) that better helps you to understand 1) how the director crafted his film, and 2) why the film has a certain effect on the audience. Think Beyond the Frame So far, we've been advising you to consider the formal aspects of a film's composition. However, as we pointed out earlier, you can write about film in several ways. Sometimes you will want to "think beyond the frame," and to consider questions about how the film was made, its historical context, and so on. For example, ask yourself: Who made the film? Find out who directed the film, and what other films this director made. If you've seen some of these other films, you'll have a better understanding of the themes and genres that the director is interested in. What is the production history of the film? See if you can find out anything about the conditions under which the film was made. Apocalypse Now, for example, has an interesting production history, in terms of its financing, casting, writing, and so on. Knowing something about the film's production can help you to understand some of the aesthetic and cinematic choices that the director has made. What do the critics and scholars say? Reading what others have said about the film before you see it may help you to focus your observations. If a film is particularly well known for the editing of a certain scene (the shower scene in Hitchcock's Psycho, for example), you'll want to pay close attention to the editing when you view the film. What can you learn from the film's genre? Before you see the film, think a bit about the norms and limitations of its genre. When you view the film, you can then consider how these limitations are obeyed or stretched. For example, Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven is a western that challenges its genre's typical notions of good guy vs. bad guy. Knowing how this dynamic plays itself out in other westerns helps you to understand and to appreciate Eastwood's accomplishment. Does the film reflect an interesting cultural phenomenon? Sometimes a professor will ask you to watch certain films because he wants you to examine a cultural phenomenon - for example, the phenomenon of stardom. Accordingly, you might watch The Scarlet Letter with the idea of viewing it as a "star vehicle," contributing to Demi Moore's star persona. Note that this sort of paper may also be a discussion of formal analysis: for example, you might discuss how Demi Moore was lit in certain scenes to emphasize her position as Hollywood star. Research Tips The most important research tip that we can offer you here is: don't rely on the Internet. While the Internet can provide some interesting information about film, it generally doesn't provide you with the thoughtful analysis that will be useful to you in your work. It's best, then, to take a trip to the library and to get your hands on books and journals. Writing Tips In many ways, writing a paper about film is no different from writing other kinds of papers in the Humanities. You need to focus your topic, write a good thesis sentence, settle on a structure, write clear and coherent paragraphs, and tend to matters of grammar and style. In some other ways, however, writing a paper about film has some challenges of its own. We've collected a few tips here: Don't simply summarize the film. Your professors have seen the film; you don't need to recount the plot to them. They are looking for analysis, not summary. Don't simply summarize the use of camera angles or editing techniques. You've annotated shot sequences in order to find something to say about them. Don't simply transcribe your annotation and call it a paper. Rather, posit something about what the director is trying to achieve, or the effect that this shot sequence has upon the audience. Don't limit yourself to a discussion of plot and characters. Some students come to film criticism trying to employ the techniques they've used to analyze novels in their English classes. They focus on analyzing the characters, themes, and plot. Film Studies papers focus on different elements of composition, as discussed above. Avoid the "I." It's too easy to slip into a subjective "reviewer's" stance when you use the "I" in your criticism. Try to find a more objective way of beginning your sentences than "I found" or "I feel." Citing Sources As in any discipline, it's essential to cite any sources that you use. Film critics cite sources using the citation method of the MLA (Modern Language Association). Glossary of Film Terms A Aspect Ratio: The height-to-width ratio of the projected screen image. Back Lighting: Lighting which comes from directly behind the subject, placing it in silhouette. Camera Angle: The position of the camera in relation to the subject determines the camera angle. 1. High angle means that the camera is looking down at the subject. 2. Low angle means that the camera is looking up at the subject. B C Cinema Verite: A way of filming real-life scenes without elaborate equipment, playing down the technical means of production (script, special lighting, etc.) and emphasizing the "reality" of the screen world. Close-Up: A shot in which a face or object fills the frame. Close-ups might be achieved by setting the camera close to the subject or by using a long focal-length lens. Composition: The arrangement of all the elements within the screen image to achieve a balance of light, mass, shadow, color, and movement. Continuity Editing: A style of editing that maintains a continuous and seemingly uninterrupted flow of action. Crane Shot: A moving shot taken on a specially constructed crane, usually from a high perspective. Cross-Cutting: Jumping back and forth between two or more locations, inviting us to find a relationship between two or more events. Cut: 1. Noun: A transition made by editing two pieces of film together. 2. Verb: To edit a film by selecting shots and splicing them together. Cutaway: In continuity editing, a shot that does not include any part of the preceding shot and that bridges a jump in time or other break in the continuous flow of action. D Day for Night: Simulating night through use of filters and underexposure. Deep Focus: A technique in which objects in the foreground and the distant background appear in equally sharp focus. Depth of Field: Distance between the nearest and furthest points at which the screen image is in reasonably sharp focus. Dissolve: Editing technique in which one shot is gradually merged into the next by the superimposition of a fade-out or fade-in. Dolly Shot: A shot taken while the camera is in motion. Dub: To record dialogue or sound to match action in shots already filmed. Dutch Tilt: A wildly tilted image, in which the subject appears on the diagonal or off-balance. E F Edit: The splicing together of separate shots. Establishing Shot: A shot showing the location of the scene or the arrangement of the characters. Often the opening shot of a sequence. Extreme Long Shot: A shot notable because of the extreme distance between camera and subject. Eye-Level Shot: A shot taken at the height of normal vision. Fade: An optical event used as a transition, in which the image on screen gradually goes to black (fade-out) or emerges from black (fade-in). Fast Motion: Representing a shot as taking place at a higher speed than it did in reality. Flat Lighting: The distribution of light within the image so that bright and dark tones are not highly contrasted. Flashback: A shot or sequence that takes the action of the story into the past. Flash-Forward: A shot or sequence that takes the action of the story into the future. Form Cut: A cut from one scene to the next on the basis of a similar geometrical, textural, or other compositional value. Frame: 1. Noun: One single picture on a piece of motion picture film. 2. Noun: The boundaries of the screen image. 3. Verb: To compose a shot to include, exclude, or emphasize certain elements. Freeze-Frame: An optical effect in which the action appears to come to a dead stop, achieved by printing a single frame many times in succession. G Glass Shot: A shot in which part of the background is painted or photographed in miniature on a glass lid and placed in front of the camera so as to blend in with the rest of the image. Hand-Held Shot: A shot made with the camera held in hand, not on a tripod or other stabilizing fixture. High-Key Lighting: Distributing light within the image so that the bright tones predominate. H I Iris: A decorative transition in which the image seems to disappear within a growing or diminishing circle. Commonly used in silent films. Jump Cut: A cut that jumps forward within a single action, creating a sense of discontinuity. Long Shot: A shot taken with the camera at a distance from its subject. J L M Mask Shot: A shot in which a portion of the image is blocked off by means of a matte over the lens, altering the shape of the frame. Medium Close-Up: A shot taken with the camera at a slight distance from the subject. In relation to an actor, "medium close-up" usually refers to a shot of the head, neck, and shoulders. Medium Long Shot: A shot taken with the camera at a distance from the subject, but closer than a long shot. Medium Shot: A shot taken with the camera at a mid-range point from the subject. In relation to an actor, "medium shot" usually refers to a shot from the waist or knees, up. Montage: 1. French: The joining together or splicing of shots or sequences - in a word, editing. 2. American: A rapid succession of shots assembled, usually by means of super-impositions and/or dissolves, to convey a visual effect, such as the passing of time. O Opticals: Any device carried out by the film laboratory and requiring the use of an optical printer. Dissolves, fades, and wipes fall under this category. Panning Shot: A shot in which the camera remains in place but moves horizontally on its axis so that the subject is constantly re-framed. Parallel Shot: When two pieces of action are presented alternately, to suggest that they occur simultaneously. Process Shot: See Rear Projection. P R S Reaction Shot: A shot of a person reacting to the main action as a listener or spectator. Rear Projection: A trick shot in which the subject is filmed against a background that is itself a motion picture screen. Upon this screen another image - either moving or still - has been projected as a backdrop. Also known as a process shot. Reverse-Angle Shot: A shot taken by a camera positioned opposite from where the previous shot was taken. Score: Music composed for a film. Set: An artificially constructed environment in which action is photographed. Slow Motion: Representing a shot as taking place at a slower speed than it did in reality. Soft Focus: A strategy whereby all objects appear soft because none are perfectly in focus. Used for romantic effect. Sound Track: 1. A recording of the sound portion of a film. 2. A narrow band along one side of a print of film in which sound is recorded. Split Screen: The division of the projected film frame into two or more sections, each containing a separate image. Stock Shot: A shot taken from a library of film footage, usually of famous people, places, or events. Subjective Shot: A shot that represents the point of view of a character. Often a reverse angle shot, preceded by a shot of the character as he or she glances off-screen. Superimposition: A shot in which one ore more images are printed on top of one another. Swish Pan: A shot in which the camera pans so rapidly that the image is blurred. T Telephoto Shot: A shot in which a camera lens of longer-than-normal focal length is used so that the depth of the projected image appears compressed. Tilt Shot: A shot in which the camera remains in place but moves vertically on its axis so that the subject is continually re-framed. Titles: Credits. In silent film, "titles" include the written commentary and dialogue spliced within the action. Tracking Shot: A shot in which the camera moves parallel to its moving subject. Travelling Shot: A shot taken from a moving object, such as a car or boat. V Voice-Over: Commentary by an unseen character or narrator. Wide-Angle Shot: A shot in which a camera lens of shorter-than-normal focal length is employed so that the depth of the projected image seems protracted. W Wipe: A transition from one shot to another in which one shot replaces another, horizontally or vertically. Zoom: The simulation of camera movement toward or away from the subject by means of a lens of variable focal length. Z * This glossary was adapted from materials distributed to film students by the Film Department at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Important Webestites - Internet Movie Database www.imdb.com - The Greatest Films of All Time http://www.filmsite.org/films.html