Using A Living Theory Methodology In Improving Practice And

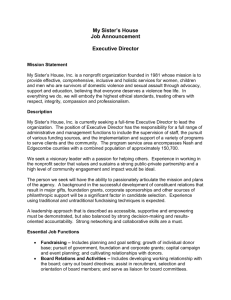

advertisement