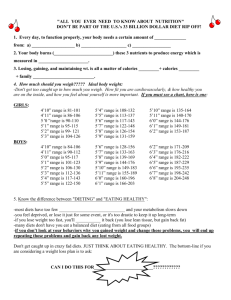

DIETARY TREATMENT OF OBESITY

advertisement