Chapter 4 - Institute of Education

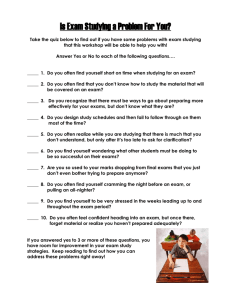

advertisement