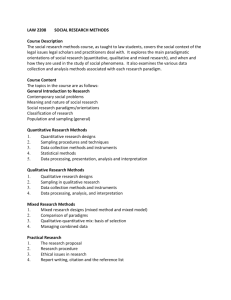

Week 7: Five Common Research Designs in Public Administration

advertisement

Week 7: Five Common Research Designs in Public Administration Part II October 19, 2010 Lecture Notes Prepared by Heather Johnston Introduction The class was instructed to each bring a hard copy of our draft outlines and the SR template, and to sit in our SR groups for the workshop with Dr. Waye. Today’s class was split into two portions: 1. Self-editing workshop with Dr. Laurie Waye from The Writing Centre 2. Lecture from Prof. Brady on Historical and Mixed Methods Research Design Note: the power point slides from Prof. Brady’s lecture are available on Moodle under Week 7 and are titled Five common research designs: part II (historical and mixed methods). 1. Self-Editing Workshop with Dr. Laurie Waye General recurring editing issues identified by Dr. Waye in our SR draft outlines 1. Wordiness – Be concise. 2. Repetition a) Within paragraphs and within the document – Ex) most entries start the same so the entire document is boring to read. b) In sentence patterns – Ex) academic writing tends to support the following habit: “Firstly/However/Thusly,…”. The placement of the comma makes the reader feel seasick! 3. Clarity – Make sure writing is focused and organized, especially at the paragraph level in the annotated bibliography. Ex) Summaries in the annotated bibliography should be organized so that the discussion of the source’s usefulness is placed together. *Dr. Waye reminded us to “feel free to write badly in drafts, then refine later”. In-Class Activity Dr. Waye handed out a page with anonymous examples taken from our outlines and instructed us to “edit as if we were the readers” for the examples appearing under the heading ‘A. Outline’. This activity highlighted two of the recurring editing issues that Dr. Waye had identified. 1. Repetition: the first example repeated the same six words in a row (“Legal assistance & court registries in…U.K./Australia/U.S.”) for three sub points in the ‘scope’ section. Dr. 1 Waye suggested instead there could be one heading (“Legal assistance & court registries”) with the countries as subheadings. 2. Clarity: the second example did not provide enough detail, so it is difficult for the reader to know where the SR is going. Dr. Waye indicated overall our outlines should have more information than our drafts. 3. Wordiness: the third example used an empty subject (“there”) and a weak verb (“is”) and contained a lot of prepositions in the ‘thesis’ section. Dr. Waye reminded us that the thesis should make a statement and grab the reader’s attention. In-Class Activity Dr. Waye instructed each SR group to pick out the wordiness and repetition in one of the paragraphs appearing under the heading ‘B. Writing Issues’. The comments from the groups and Dr. Waye are as follows: Alaska Court System – group and Dr. Waye said wordy and repeated “website” and “help line” BC Stats’ Work Environment Survey – group said it is unclear what is being measured. Dr. Waye said to state why the source is useful for the SR and to include that information at the beginning of the paragraph. Government wide human resource plan – group said organization of the paragraph and some of the phrases used were unclear. Dr. Waye said don’t assume the reader has read the bibliographic information. All parts of the SR must be understandable on their own. Athabasca University – group made no comment. Dr. Waye said there is so much information contained in this paragraph it is difficult to be concise. New building materials in construction industry – group said the second sentence is a run on sentence. Dr. Waye said this is an example of a comma splice, which occurs when two independent clauses are joined (in error) by a comma. *Dr. Waye reminded us “These are editing, not writing issues.” The workshop portion of the class concluded with 10 minutes to work in our SR groups to look for these problems in our drafts. Dr. Waye, Prof. Tedds and Brady and staff from KIS (Melissa and Paige) provided feedback to each SR group. *Final comment from Dr. Waye: “Apply the rubric and follow the SR template”. Contact information for Dr. Waye Phone: 250-853-3675 Email: twccoor@uvic.ca 2 2. Lecture on Historical and Mixed Methods Research Designs with Prof. Brady Purpose An introduction to the key features of two research designs: historical and mixed methods. Research designs are the epistemological/philosophical link to the research methods. We will be introduced to research methods in subsequent lectures. ADMN 502a is organized as follows: Research Philosophy Research Design – underpinned by the epistemology Research Methods – informed by the research design Data Analysis – depends on the data collected as defined by the research methods This course structure is a natural progression as each preceding topic informs the subsequent topic(s). Brief Review of Research Philosophy Ontology asks what exists? Epistemology looks at the relationship between the researcher and the subject Methods are usually associated with the research philosophy *Prof. Brady reminded us that research philosophies underlie everything we are talking about and suggested that we try to organize what we are learning into these boxes. Historical Methods Historical methods involve use of documents, data, books, archives, and objects from previous periods 3 Different Aims (based on Research Philosophy) 1. To create empirical generalizations about the social world (positivist) 2. To piece together a picture of theories and views that were held in the past (hermeneutic – to understand the worldview of a group) 3. To illustrate how contingent and historically specific our present theories and views are (post-structuralist – to see how theories and views are constructed historically through language) Positivism and historical methods History contains facts and events that should be systematically analyzed to make generalizations. Commonly uses quantitative methods, but may use qualitative methods. Ex) the democratic peace thesis – a general social law that states ‘democracies never go to war against each other’ (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Democratic_peace_theory) Quantitative approach: 1. Define the dependent and independent variables Ex) variables in the democratic peace thesis: Independent = democratic/non-democratic Dependent = peace/war outcome 2. Develop a database (or locate an existing one) 3. Employ statistical techniques to determine the relationship between the independent and dependent variables Critique of positivist approach: History does not contain neutral facts – they are defined historically. Variables (and analytical concepts used to create them) are historical objects – that embody power relationships. Variable may be products of political processes. Ex) definition of democratic - President Woodrow Wilson originally stated that Germany was a better democracy than France, but changed his opinion when the USA was about to go to war with Nazi Germany and stated Germany was a dictatorship. It was not really Germany that had changed; it was the way Wilson was defining Germany that was different. Historical methods & interpretive, reflexive approaches (non-positivist) 4 Hermeneutic approach: Piece together different bits of information to generate a clear, coherent picture. Ex) Picture of Wilson and Burgess’ views on democracy – because they changed over time (see Oren, 2006) Post-structuralist approach: Illustrating the historical variability of categories and meaning. Ex) Foucault, and the categories in a Chinese encyclopedia, for example ‘belonging to the emperor’ or ‘being embalmed’ – the categories seem so strange to see the world that way, therefore categories are specific to what created them. Ex) Oren, on Wilson and Burgess’ emphasis on racial categories – because their categories of race linked Aryan nations back to the Greeks and therefore to democracy. So Oren argued that if we don’t accept the race categories why do we accept the definition of democracy? (see Oren, 2006) Reflexivity: Making “social and intellectual unconscious embedded in analytical tools and categories” visible (Bourdieu & Wacquant) Ex) Oren and the democratic peace thesis combines elements of hermeneutic (looking at Wilson & Burgess) and post-structuralist (looking at Wilson’s changing definition of democracy) and has a reflexive approach (examining how we came to see peace and democracy this way). Historical Methods – Summary Historical methods can be combined with any of the four (positivist, post-positivist, hermeneutic, post-structuralist) epistemologies. The way that historical ‘data’ is used will vary depending upon underlying epistemological stance. Positivist – history as repository of facts. Researcher finds variables and relationships between them. Hermeneutic – history does not contain neutral facts. Aim is to build up a picture of groups’ or individuals’ views to develop a picture of the past. Post-structuralist – history does not contain neutral facts and this has implications for our present. Uses history to speak to and question some of the present categories. Mixed Methods Mixed methods are a research design that involves the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods based on the belief that the combination of both methods provides a better understanding of a research problem. Mixed methods can also be defined as a research design that includes philosophical assumptions (see Cresswell, 2009). 5 Types of mixed methods Creswell et al. (2003) identify six mixed methods research designs based on the following categories: Timing of methods Weighting (prioritizing) of methods Mixing of methods (how is it done) Theorizing (is it explicit) Timing Two broad options of qualitative and quantitative data collection: 1. Sequential – collect and analyze one type of data first. Then collect and analyze the other type of data. 2. Concurrently – collect both types of data at the same time. Then analyze both at the same time. Weighting (Prioritizing) How priority is assigned to qualitative and quantitative methods: Equal weight Qualitative over quantitative Quantitative over qualitative Mixing When does the researcher mix the data? Data collection? Data analysis? Data interpretation? All three stages? How does mixing occur? Findings merged? Findings kept separate? Something between the two of these extremes? Three types of mixing 6 1. Integrating – really bring the two together. 2. Connecting – Ex) Stats Can information shows one third of adults between 30 and 40 years of age volunteer, in the focus group this came up… 3. Embedding – taking a whole body of research with excerpts of one type into the other. Theorizing Design guided by larger explicit theoretical perspective. Design NOT guided by larger explicit theoretical perspective. - The ‘larger explicit theoretical perspective’ could be social science or policy. Ex) are south east Asian women affected by patriarchy in the same way that white women are in London (Bhopal, 2000 as cited in Cresswell, 2009). Looked at theories of patriarchy through a feminist lens. Six mixed methods of designs (See Creswell, 2009 for discussion) Sequential Designs 1. Sequential explanatory strategy – what causes what? Why does ‘x’ happen? Used by strongly positivist & quantitative researchers Quantitative data usually prioritized Quantitative collected first & informs qualitative data collection May or may not have an explicit theoretical perspective Ex) New Hope study (see http://www.mdrc.org/project_8_30.html) - The New Hope program was designed to supplement income of low income people living in high poverty areas of Milwaukee. First, quantitative data was collected from two years of information on unemployment insurance, food stamps, etc. Then an ethnographic study of 46 families was conducted and found that different people had different ideas as to the benefits of taking up the services. Researchers were interested in explaining why some people were not accessing all the services that were available to them. 2. Sequential exploratory strategy – trying to understand Reverses the stages of the sequential explanatory strategy (qualitative data is collected first), still quite positivist Usually used to: -Test a theory emerging from qualitative research (Morgan, 1998) 7 -Generalize qualitative findings, from descriptive data taken from a small sample -Develop a new data collection instrument for survey research 3. Sequential transformative strategy Aim is to be able to conclude study with a call to action There is an explicit theoretical lens (gender, race, social science, OR public policy theory) Either qualitative or quantitative can be used first and either may be prioritized Ex) Bhopal (2000) looked at ‘gender, “race” and power in the research process’. Ex) SR topic, client has the idea that employees using social media have better engagement with the public. This sets out the aim of the project and the theory. Ex) 598 Critique topic, engaging young adults study, the United Way wanted to know how to engage youth in a long term volunteer relationship. Note: this design does not really fit with academics because it is not appropriate to make recommendations in academic research Q – Does having the end goal of a specific aim give rise to bias? A - In the sequential transformative strategy there is no theory going in to the research stage about how to achieve the transformative call to action, the goal is to find the call to action. Concurrent designs 4. Concurrent triangulation strategy – using one method to verify results from another (weaker) source Key term = triangulation, which is the combined use of multiple methods or different levels of study (micro & macro) using each to complement and verify the other, in order to achieve robust research results (Oxford dictionary of sociology). Most common mixed methods design Aim is to offset the weakness of one method with the strengths of the other Qualitative and quantitative data collected concurrently and each method given similar weight 5. Concurrent embedded strategy – primary interest is does this method work? Similar to concurrent triangulation strategy except that one of the methods is given priority 8 Ex) in an experiment quantitative methods measure the outcomes while qualitative methods are used to explore experiences of the treatment group. Qualitative data fills out the research. 6. Concurrent transformative strategy – trying to solve something at the end As with the sequential transformative strategy researcher is guided by theoretical perspective Only difference between this design and the sequential design is that the qualitative and quantitative data are collected concurrently The way they are mixed is guided by the theoretical perspective and research questions Lecture Summary Research design must be considered together with underlying epistemology. Epistemology guides the specifics of the research design in each case. Positivist: seek to establish generalizations and see facts as neutral using case studies, comparative studies, historical studies, mixed method studies. Hermeneutic: seek to establish an empathic picture of events and beliefs using case studies, comparative studies and historical studies. Positivist-hermeneutic: aim to achieve an outside objective perspective on a problem and understand this problem from the perspective of a specific group and how it shifts over time, therefore this requires a mixed method research design. There are not a lot of examples of this because it is the least common at the moment, however its use is increasing in policy research. Contact information for Prof. Brady Phone: 250-721-8063 Email: mabrady@uvic.ca Concluding Remarks/Next Week Unfortunately we ran out of time today, and the lecture on the fifth common research design (experimental) was moved to next week, October 26, 2010. We will begin our discussions on surveys and interviews (Research Methods) In subsequent weeks we will look at data analysis We hope you feel better Prof. Tedds! 9