Brenda - UH History

advertisement

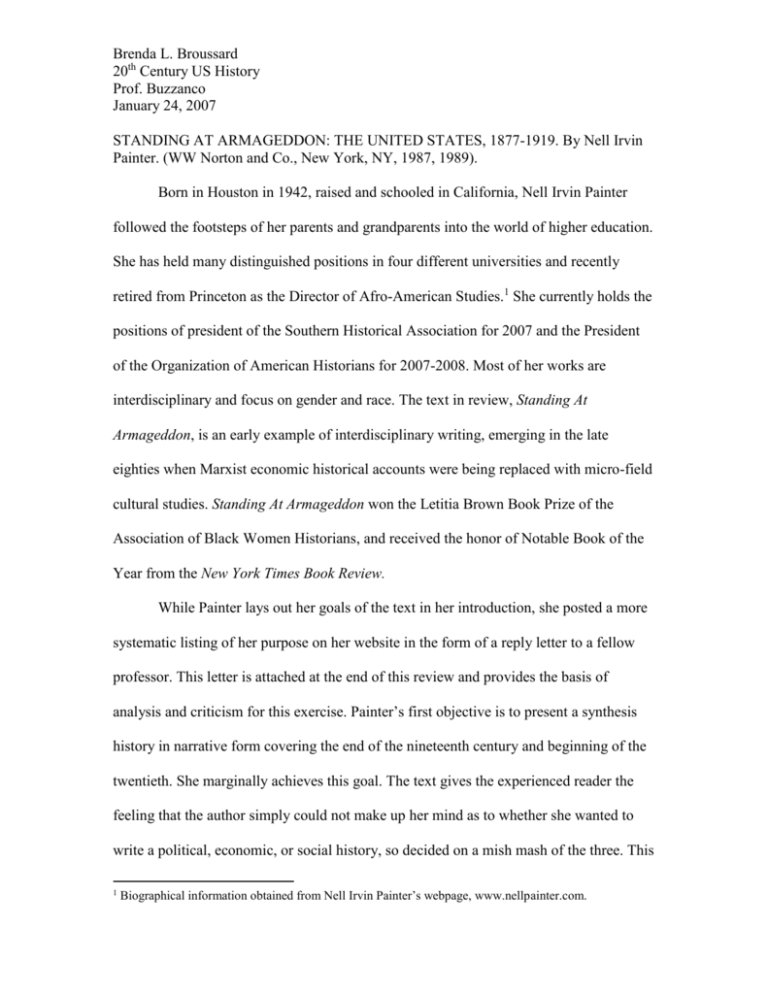

Brenda L. Broussard 20th Century US History Prof. Buzzanco January 24, 2007 STANDING AT ARMAGEDDON: THE UNITED STATES, 1877-1919. By Nell Irvin Painter. (WW Norton and Co., New York, NY, 1987, 1989). Born in Houston in 1942, raised and schooled in California, Nell Irvin Painter followed the footsteps of her parents and grandparents into the world of higher education. She has held many distinguished positions in four different universities and recently retired from Princeton as the Director of Afro-American Studies.1 She currently holds the positions of president of the Southern Historical Association for 2007 and the President of the Organization of American Historians for 2007-2008. Most of her works are interdisciplinary and focus on gender and race. The text in review, Standing At Armageddon, is an early example of interdisciplinary writing, emerging in the late eighties when Marxist economic historical accounts were being replaced with micro-field cultural studies. Standing At Armageddon won the Letitia Brown Book Prize of the Association of Black Women Historians, and received the honor of Notable Book of the Year from the New York Times Book Review. While Painter lays out her goals of the text in her introduction, she posted a more systematic listing of her purpose on her website in the form of a reply letter to a fellow professor. This letter is attached at the end of this review and provides the basis of analysis and criticism for this exercise. Painter’s first objective is to present a synthesis history in narrative form covering the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth. She marginally achieves this goal. The text gives the experienced reader the feeling that the author simply could not make up her mind as to whether she wanted to write a political, economic, or social history, so decided on a mish mash of the three. This 1 Biographical information obtained from Nell Irvin Painter’s webpage, www.nellpainter.com. Broussard 2 lends the context a scattered form with each portion of a chapter resembling a vignette unrelated to the previous or following anecdote. This does not mean that the text is of little merit. It would serve nicely at the undergraduate level as a survey reference text. Painter rarely delves deeply into the various little narratives that sew her text together, therefore versed academics need to provide additional explanation and analysis when used at the lower collegiate levels. Graduates might find the text useful as a refresher text that highlights the major events and agents of the era. For undergraduates, her scattered methodology warrants merit in that is exemplifies how diverse American society was during this time. Often it is difficult to convey that industrial labor strikes were occurring at the same time that Indians and frontiersmen were battling it out on the mid-west plains. Painter’s short, jumpy style lends to the rapidly changing atmosphere of the era she is explaining. The author’s next goal was to show where the money came from and where it went. It is here that her personal bias towards the dispossessed and marginalized is evident on every page. Capitalists are clearly the antagonists in history, according to Painter. She sets the stage in her first two chapters by discussing labor, labor movements, labor unions, strikes, and their relationship to politics. In a whirlwind of names and places, Painter provides a laundry list of all the key players in the embryonic American labor movement. In chapter three, Painter discusses the abnormal distribution of wealth that industrialization created in the United States and the proposed “remedies.” These remedies include tariffs, currency and banking reform, antitrust and monopoly policy. She points to a general acceptance by the masses of corruption in politics as the norm. Painter nicely spells out in easily discernable language where the Democratic and Broussard 3 Republican parties stood on each of these issues and even provides some analysis on the differing logics. In chapter four Painter elaborates on the bimetal-paper currency debate and discusses several more pivotal labor strikes during the 1890s Depression. Following Painter’s letter, she achieves her third goal of including ordinary people in her text. However, luminaries take center stage, and ordinary people are often just the masses involved in the numerous violent incidents she catalogs. A strength of the book is that Painter leaves no stone unturned, even if only slightly. She mentions an abundance of groups and their roles in altering domestic policies by their socio-economic standing, race, gender, religious affiliation, political association, geographic location, etc. This is where her little vignettes add a degree of depth to the text. Chapters five, ten, and eleven concentrate on foreign wars, and how foreign policy affected domestic policy, and the final chapter deals with the aftermath of World War I. Dispersed throughout these chapters are issues of expansionism, colonialism, racial hierarchy, and interventionism. Chapters 6, titled “Prosperity,” returns to the capitalists are evil theme, as Painter enumerates the most prosperous of trusts at the turn of the century and their role in the poverty of the masses. Chapters seven and eight only briefly examine race and woman suffrage. This is not a weakness, oversight, or afterthought, because Painter deals with women and the disenfranchised throughout the entire text. Overall, the author meets her goals. An ambitious undertaking once the reader realizes just how numerous the issues are that Painter covers in Standing At Armageddon. There is no bibliography, but there is a modest index. Painter’s sources are largely secondary, which is not unusual for a synthesis history. Standing At Armageddon would Broussard 4 be an excellent text for undergraduate survey courses in post-1877 American history or early American labor history. Graduates will find the text too generalized for a readings course, but a good source for jogging their memories of certain key events, especial those involving labor strikes. Broussard 5 The following is a reply from Painter to Professor Zeidel on how best to use Standing At Armageddon in the classroom. 5 October 1999 Good Afternoon, Professor Zeidel, Thanks for your gracious comments about STANDING AT ARMAGEDDON. I'm delighted that readers are finding the book interesting and useful. What follows isn't exactly an outline, but I hope it'll give your teachers a clearer sense of what I wanted to do in the book. ARMAGEDDON aims to show readers: 1. What happened. Having read a million American history books in which the writer engages other historians without letting readers know the events and figures being discussed, I wanted to lay out a narrative political history that clearly explained important events and people in the national political life of the period. 2. Where the money came from and where it went. I thought it important for readers to understand the economic issues that lay at the bottom of crucial political controversies, especially taxation--including tariffs and income taxes--currency, and the federal reserve system. 3. Ordinary people's part in national political history. Because most Americans at the time were (and still are) working people, their situation and their influence on the political economy of the time lie at the center of ARMAGEDDON. 4. The integration of international issues with domestic policy, which is how Americans experienced them. Therefore the chapters on foreign wars explain how they played out in domestic politics, and when Woodrow Wilson goes to Paris and Versailles, ARMAGEDDON remains focused on American domestic issues--such as inflation and strikes. 5. A definition of "Americans" that doesn't exclude people whose citizenship was compromised, e.g., white women and people of color. All in all, I didn't want ARMAGEDDON to come off as a provincial American history with blinders on. Best Wishes, Nell Painter2 2 Taken from www.nellpainter.com