Doing business with gender: the case of business history in the UK

advertisement

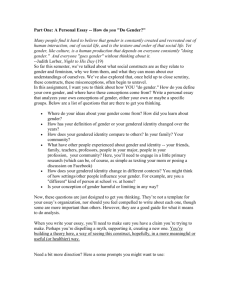

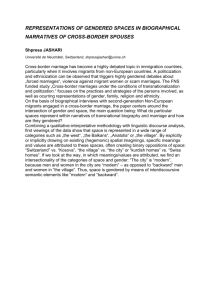

Draft ‘Doing business with gender: the case of business history in the UK’ Katrina Honeyman European Business History Association Conference Barcelona 16-18 September 2004 1 Doing business with gender: the case of British business history in the UK In many areas of political, social and economic activity the gap between the US and the UK is wide, but with respect to engendering business history a chasm separates the two. Business history has from the outset been more precocious in the US; and progress has continued to be faster there than in GB.1 In the United States lively and frequent discussion at conferences and on the pages of learned journals testifies to the intellectually innovative climate of business history, which, in recent years has explicitly included gendered business history.2 In Britain by contrast and despite specific pieces of individual research which challenge existing boundaries, and in spite of awareness that paradigmatic progress is required, there is limited engagement with broad issues concerning gender and business.3 This paper aims to present an overview of the state of gender and business history in GB, and to offer suggestions for ways forward. It consists of four stands. Firstly an assessment of and an explanation for the current situation is offered. This will include a discussion of both institutional constraints on women’s entrepreneurial or managerial activities, and the scholarly environment within which a study of the history of such activity takes place. Secondly it will explore the changing gendered environment within which business operates; and emphasise the need for business history to keep pace with such change. The third strand of the paper identifies positive features of recent business history developments, and explores ways in which these can be used to engender further the enterprise of business history. Finally it will make the case for an embedded gendered business history. 2 I Business history in GB The roots of British business history can be located in economic history, itself a discipline preferring a concrete, even quantitative base. From its early days as an independent discipline, the conceptual base of business history was informed by notions of structure, efficiency, rationality and profitability, and as such attention was focused on robust, quantifiable elements to the neglect of socio-cultural forces. Above all it seemed to be a discipline driven by empiricism with theoretical discussions languishing ‘in the doldrums’ according to Wilson4, and where theoretical work existed, suggests Rose, it ‘concentrated on efficiency of specific forms of organisation rather than on the human relationships that underpin them’.5 Reviews of the periodical literature over the last decade, indicate continuity in perceptions of the nature of discipline, and four main themes can be discerned. Firstly that British business historians are neither clear nor agreed about what constitutes their subject.6 Secondly, that they produce eclectic work on diverse subjects, ranging from narrow empirical case studies to broad and general sweeps. Thirdly the subject continues to be characterised by methodological variation and interdisciplinarity, which can indicate ‘strength in depth’7 and the promise of excitement through diversity8, but can also create a ‘barrier, since it creates different languages and makes it impossible for historians from different methodological backgrounds to talk to one another’.9 Generally, however, the ‘endless novelty’ of research in business history ‘suggests an optimistic future for the discipline of business history’.10 3 Amidst all this eclecticism and indeed the continued search for new paradigms11 , it is surprising how little enthusiasm for gendering business history there has been, a point taken up by an American reviewer of the British periodical literature. There should be, argued Blackford, be ‘more of an effort to move in new directions… [especially] … the role of gender and race… in business development’.12 The discipline may have moved on, but the ‘mainstream’ or ‘malestream’ has continued to focus on measurable issues. In recent years renewed enthusiasm for quantification and the manipulation of data sets has been evident.13 Qualitative aspects are marginalised and only in isolated pockets has the gendering of British business history made progress. Possible explanations for this include the deep rooted desire to cling to the concrete, as well as institutional constraints and perceptions of gender as subversive. Traditional business history has been gender blind. This may be the result of longstanding barriers to women’s entrepreneurial and managerial activities, which creates an impression that the world of business is dominated by men. It may also be the result of the male dominance of the practice of business history in Britain, as reflected in a gender analysis of the participants at mainstream business history conferences.14 However, while this may explain the invisibility of women in business activity and in the exploration of its history, it does not explain why gender [that is, the social construction of masculinity and femininity; or the interaction of men and women] should be ignored. It could be argued that male British business historians find it easier to consider only what it visible [men] rather than to question why a potentially important driver of business activity15 is either absent or underrepresented. This offers further evidence for the notion that the dominant rarely reflect on their dominance while the oppressed are more inclined to dwell on their oppression.16 4 Women’s historians are accustomed to digging deep and imaginatively to retrieve their history; while male historians are less likely to do this because they already have plenty to look at. The ‘taken for granted’ masculinity which permeates business activity and the study of its history in fact embodies ideological notions of gender hierarchy and power. Although ‘gender’, as a conceptual approach to historical understanding, does not constitute a challenge to male dominance, but rather aims to make this dominance transparent and to explore it, reluctance to engage with it may be based on such concern. The recent growth of work engaging with notions of masculinity has the potential to provide gendered business history with the required counterpoise. This will be explored further below. The lack of gendered insights in British business history also has to do with the institutional development of women’s and gender history. This has progressed more slowly as a separate discipline in Britain than in the US , and is often lost in ‘mainstream’ history departments. At the same time business historians are employed either in Management or Business Schools or in faculties of economics. Either way little institutional opportunity exists for ‘gender historians’ and business historians to engage in dialogue. A difference also exists between the US and GB in the way in which the respective disciplines of women’s history and gender history have developed. American practitioners have demonstrated a preference for women’s history, while at the same time producing influential insights into gender, and this is reflected in much of their business history. In Britain, it could be argued that while gender history has gained ground at the expense of women’s history, gender 5 historians have not yet been greatly enthused by the project of business history. So, the sluggish progress of gendered business history in Britain is not only the outcome of the failure of male business historians to contemplate gender issues, but is also the result of gender historians – be they male or female – failing to pursue their concerns within business history. II The gendered context of business and its history These are possible explanations but not justifications; and if British business history continues to ignore or marginalise gender, it will not only be the poorer for it, but will fail to adequately reflect the context within which it operates. Business is not a discrete sphere based on a distinct value system; both business activity and its history are influenced by beliefs and practices developed externally. Much recent research has demonstrated not only that gender is a social construct changeable over time, but has fluidity at any moment, and is subject to continual renegotiation.17 Broad changes in gender positions over the past several centuries and the way in which these changes occurred inform the gendered context of business. During the medieval period, for example, access to business and trading opportunities was not much affected by gender, though there is evidence that economic crises generated gender conflict, and attempts to exclude women from business by raising institutional barriers were generally successful.18 Constraints on women’s commercial activities dissipated somewhat during the eighteenth century only to be reinforced again during the nineteenth century, this time by the manipulation of gender roles and 6 identities as well as legal and commercial institutions.19 Through the twentieth century gender roles converged, men and women gradually came to participate in the same spheres, and in principle, supported by educational progress, second wave feminism and equality legislation, access to business opportunities – while still influenced by class and ethnic positions – was less constrained by gender.20 Such trends were mirrored in access to work and occupational choice. Having been constructed as secondary workers in both periods of significant gender conflict but most enduringly in the context of industrialisation, women were confined to relatively low skilled and poorly paid work. The most recent statistics demonstrate significant progress in equalising occupational opportunities but while women currently comprise 50 per cent of the workforce in the UK,21 largely the result of the expansion of service sector activity, and the flexibility of work offered within that sector, they continue to dominate less rewarding, and most exploitative work.22 Accordingly women occupy only a small proportion of managerial positions and although upward mobility within careers is increasingly achieved, very few women have broken through the glass ceiling. The board rooms of companies both large and small remain resolutely male. During the twentieth century, therefore, the economic and social position of men and women showed signs of converging, but inequality in the nature of work, the level of wages, and the extent of upward mobility, persists.[Table 1] Table 1 Socio-economic group by sex, 1975-94, [percentage] SOCIO-ECONOMIC GROUP 1975 1985 1994 Professional 5 6 7 Employer/manager 15 19 21 MEN 7 Intermediate and junior non-manual 17 17 17 Skilled manual, own account 41 37 35 Semi-skilled manual, personal service 17 16 14 Unskilled manual 5 5 5 Professional 1 1 2 Employer/manager 4 7 11 Intermediate and junior non-manual 46 48 48 Skilled manual, own account 9 9 8 Semi-skilled manual 31 27 22 Unskilled manual 9 7 9 WOMEN Source: OPCS 1996: Table 7.4. Taken from Walby, Gender transformations p35 Thus the broad external context of business is gendered, even if the nature of that gendering has changed over time. Gender also operates in subtle, ‘internal’ ways. It is suggested here that gender constructs and gender identities play a crucial if sometimes intangible part in the creation of business culture. Although gender is a social construct, it need not be constructed identically in all spheres of society.23 So gender might be constructed differently in business activity, than, say, in religious activity; or that it might be constructed differently in different businesses. For example, it might be possible to identify a gendered preference for particular kinds of business, with relevance for service sector activity. The basis for such preference might be cultural tradition or historically specific and socially constructed gender roles. In Britain, women’s self-employment or business activity has been traditionally located in smallscale trading and marketing, caring, nursing, midwifery and other personal services. 8 These might be considered to be female-specific activities on the basis of both socially constructed roles but also because – in the context of gender segregation – these were the only kinds of activities open to women. Historically it has also been difficult if not impossible for women to supervise or to manage men because of their socially determined position, which has constrained their activity within many ‘male’ activities. Therefore, women’s business activities have been heavily based in the service sector. The construction of gender is also relevant to an understanding of wider notions of business. For example, where the gender of the consumer is important, such as in the case of the men’s clothing trade, the business historian might learn much about business strategy, by exploring the making of the male consumer through the manipulation of notions of masculinity.24 It is also possible that the gendering of business objectives and performance measures might also offer valid insights. Success in business, for example, might be perceived differently by women and men. Men, more than women, may be driven by the bottom line; women more than men by issues of community, social justice and environment.25 Women in business and women’s businesses have in the past, been judged as exceptions to male indicators of success, rather than as ‘part of the gendered history of economic life’.26 Such issues relate to the culture of business; and each business may have a different ‘culture’ determined at least partly by the gender of its participants.27 It is time to take more account of these aspects. III Progress: services and gendered business history 9 Gender may be a useful category of analysis, but it has not yet proved popular in Britain at least.28 Despite the failure of the mainstream of British business history to embrace gender, practitioners of women’s history and gender history have reclaimed much of women’s hidden past, most successfully in the context of labour and work in British industrialisation. In doing so, an understanding of the process of industrialisation has been enhanced. There are good reasons for expecting an equivalent outcome to apply to the gendering of business history, not least because the areas in which a gender approach has already proved itself, are closely connected to, if not part of, the world of business. Examples of recent contributions can be grouped into three categories. Firstly, work that has identified women’s activity where it – and equally women’s talents and abilities - had previously been ignored or underplayed. This work includes women’s business dealings, often located in the service sector, such as Pamela Pilbeam’s analysis of the creative entertainment business of Madame Tussaud29, and Leonore Davidoff’s work on Victorian landladies30, both of which confirm the special ability of women from different social groups to identify and seize business opportunities, while at the same time conforming to socially determined positions. Women’s facility with financial dealings is demonstrated by several recent pieces of influential research, including Beverly Lemire’s work on the importance of women’s role in establishing and utilising credit networks in early industrial England; Judith Spicksley’s analysis of the role of single women in lending and information networks in seventeenth century England; and Alison Parkinson Kay’s work on women’s selfemployment in nineteenth century London.31 Nicky Reader’s research on Female Friendly societies illustrates women’s competence in organising both social and 10 actuarial aspects of clubs and associations, and promises to generate a gendered analysis of what has, until now, been viewed as an exclusively male world32. Women were often to be found operating at the interface of making and selling, as exemplified by Stana Nenadic’s study of the Edinburgh women’s garment trades, which demonstrates that such activity went beyond profit maximisation but rather emphasised ‘non-utilitarian satisfactions’.33 Such work not only adds to our knowledge of the history of entrepreneurial activity, but also suggests alternative ways of thinking about the shape of business and the nature of success. Women’s enterprise may well have been located at the petty end of the market, often satisfying working class demand, and demonstrating how self-employment can emerge out of labour, thus offering an upwardly mobile path, but this is surely no justification for ignoring what was clearly a sizeable proportion of total British business activity. 34 On the contrary, greater attention to such activity would clarify the heterogeneous nature of British business. The second category of work demonstrates how a gendered analysis, and especially a focus on the construction of gender identities enhances an understanding of how organisations, businesses and markets operate. Recent research in this category has also paid particular attention to service sector activity. Robert Bennett, for example, explores the use of the marriage bar in the clerical and service sector, with particular reference to the British Civil Service and Barclays’ Bank. He argues that the constraint on married women’s work helped to construct a particular organisational culture emphasising middle class respectability through the gendered family form. He uses his findings to suggest that gender, and culture more widely should be prioritised in the analysis of British business, and that to maintain a ‘position in which culture is 11 subservient to economic forces….. risk[s] a retreat into both functionalism and essentialism’35. Other work on service sector activity, including research on insurance companies, confirms the range of ways in which gender identities were reconstructed in the context of sectoral change in the British economy from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries. 36 The third category of research that demonstrates the fruitfulness of a gendered approach is at an earlier stage of development and therefore more speculative, but suggests great promise. Work by Jean Gardiner and others explores the ways in which skills acquired by women within the domestic sphere have value within the wider economy including business. Gardiner’s argument is that the experience accumulated by women through organising a home and family, and engaging in a variety of caring and educative roles, equips them well for the world of business; and that these skills should be utilised and valued.37 Such an approach is compatible with the work of Walby who argues that by failing to maximise the capabilities of women, business and the economy are impoverished.38 The second reason why a gender analysis would both enhance business history and should not be too difficult to apply, is that some practitioners of business history have developed areas of interest which are compatible with the conceptual apparatus of gender history. The culture of business, of which gender is a part, is a good example. This has informed US business history for some time, and for rather less time in Britain where economic concerns continue to take precedence over those of culture. Yet the desire to measure – while still very strong – is being joined by an acceptance of the need to explore the more qualitative features of business activity. The 12 contribution made by Mary Rose to this area is particularly important. While not an explicit practitioner of gendered business history, Rose has nevertheless shown how the ‘human’ aspect of business, reflected in networks and culture, can illuminate the analysis of business activity.39 Through the work of Rose and others, the potential for convergence can be seen, as well as the possibilities for using gender analysis to enhance the understanding of business. And in principle, because there is no dominant framework, or at least because the previously dominant framework is being challenged; and because business historians are only too aware of the need to draw upon relevant discourses because of the heterogeneity of their subject matter and mode of interrogation, then a gender approach should not be too intrusive. IV The future The conclusion to this paper takes the form of an agenda. Before progress can be made, current distortions in business history driven by inherent maleness, and the universal importance of gender, need to be recognised.40 Business history as a discipline has a traditional receptiveness to new ideas, even if individual business historians tend to be ideologically blinkered. While the history of women’s businesses has tended to demonstrate the exceptional nature of female entrepreneurship, and thus made it easier for the malestream to ignore or marginalise it, which strengthens the case for a ‘gendered’ business history, it could equally be argued that by making women more visible, the predominance of men will also become more visible. Such clarity will facilitate acknowledgment of an ideological framework, that economic laws and practices are neither value free nor naturally conceived. 13 At this point it is appropriate to revisit the distinction between women’s [business] history and gender [business] history. The former prioritises women in order to identify their practices and achievements, and is necessary in order to redress the balance. But it is separate and suggests that women are inevitably ‘different’; and can therefore be marginalised and ignored. The latter embraces activity of both men and women, and attempts to understand their interaction, their complementary contributions and the way in which their ‘differences’ have been at least partly socially constructed. The gender history approach, because of its inclusiveness, is one that I advocate. Building on an acceptance that gender has been neglected and that it is not threatening, the progress already made in the area of ‘culture’ can be developed. The challenge will be to clarify the links between culture and gender. One way in which this might be done is to explore more fully the categories of masculinity and femininity which are defined by culture and subject to historical change. Femininity has been thoroughly explored, and often assumed to be incompatible with entrepreneurship, while masculinity, assumed to be more in tune with the world of business, has not so often been fully specified. The construction of masculinity [or masculinities] deserves as much attention as that of femininity. Perhaps the time has come to shift the balance. Then, it will be easier to ask questions about the gendered organisation of the business world, and accept that gender relations in business should become an essential part of historical analysis. Given the small numbers of women currently practising business history in the UK, and by no means all of these are convinced by the gendered approach, the gendering of business history will have to 14 become a gender inclusive enterprise. Men must become aware of its value and practicality. The pursuit of business goals are perpetuated through gendered practices. Business history needs more than economic analysis for its complete understanding. Gender may lack tangibility, yet it provides valuable insights into the operation of business in the past. 1 John F Wilson, British business history 1720-1994, 1995, p1; Barry Supple Essays in British business history 1977, p1. This is also implied by Mary Rose in Firms, networks and business values. The British and American cotton industries since 1750, 2000, pxi where she argues that the performance of British business has so often been judged from an American perspective. 2 The Hagley conference on the future of business history for example. Some differences between the US and GB are alluded to in Katrina Honeyman ‘Engendering enterprise’ Business History, 2001, pp119-126 3 Trevor Boyns suggests that business historians in Britain discuss methodological issues much less than is the case in other countries. ‘British business history: Review of the periodical literature for 1996’ Business History 1998 p96 4 John F Wilson ‘British business history: a review of the periodical literature for 1992’ Business History 1994 p1 5 Mary Rose, ‘Networks, values and business: the evolution of British family firms from the eighteenth to the twentieth century’ Entreprise et histoire 1999 p19 6 Boyns ‘British business history’ p95 7 Michael French ‘British business history: a review of the periodical literature for 1997’ Business History 1999, p11 8 Duncan Ross, ‘British business history: a review of the periodical literature for 1998’ Business History 2000, pp12-13 9 Boyns, ‘British business history’ p96 10 Steven Toms ‘British business history: a review of the periodical literature for 2000’, Business History 2002, p13 11 Steven Toms and John Wilson ‘Scale, scope and accountability: Towards a new paradigm of British business history’, paper to ABH conference, University of Cambridge, 2003 12 Mansel G Blackford, ‘British business history: a review of the periodical literature for 2001’ Business History 2003 13 For example, David Jeremy made the case for ‘innovative’ work in this area in ‘New business history?’ Historical Journal 1994 pp717-28 14 For example, participants at the past two conferences of the Association of Business Historians were not only overwhelmingly male, but the majority of those women attending were either graduate students – clearly a good thing in terms of future development – or visiting scholars from the US or the continent of Europe. 15 Here race and class are relevant as well as gender 16 Catherine Hall, ‘Politics, post-structuralism and feminist history’ Gender and History 1991 17 Scott, Jutta Schwarzkopf, Unpicking gender. The social construction of gender in the Lancashire cotton weaving industry, 1880-1914 2004; Katrina Honeyman Women, gender and industrialisation in England 1700-1870, 2000. 18 Katrina Honeyman and Jordan Goodman ‘Women’s work, gender conflict and labour markets in Europe, 1500-1900’ Economic History Review 1991; B Hanawalt [ed] Women and work in preindustrial Europe 1986; Mary Prior [ed] Women in English society 1500-1800 1985. 19 Honeyman and Goodman ‘Women’s work’. 20 For example Sylvia Walby Gender transformations 1997 21 But not 50 per cent of the hours worked. Women, to a much greater extent than men, work part time. 22 Sylvia Walby Gender transformations 1997; Margaret Walsh and Chris Wrigley, ‘Womanpower: the transformation of the labour force in the UK and the USA since 1945’ Refresh, 30, 2001 23 Schwarzkopf, Unpicking gender p3 15 Katrina Honeyman, Well suited. A history of the Leeds clothing industry 1850-1990; ‘Following suit: men, masculinity and gendered practices in the clothing trade in Leeds, England, 1890-1940’ Gender and History, 14, 2002, pp426-446. The female consumer was constructed in a different way, as for women, consuming, or shopping, was perceived to be an activity consistent with their ‘nature’ or accepted behaviour. 25 Angel Kwolek-Folland makes the suggestion that women’s participation in business may be influenced by domestic experience and internalise values other than pure profit and individual success, in ‘Gender and business history’, her introduction to Enterprise and Society special issue, 2001 26 Wendy Gamber, Gender and business history’ Business History Review 1998, p191 27 As Alice Kessler Harris suggests, if ‘we want to approach a multi-dimensional perspective, we need to be aware of the full range of cultural signals that guided decision making at all levels’. ‘Ideologies and innovation: gender dimensions of business history’, Business and Economic History 1991, p51 28 Scott ‘Gender and business history’, Business History Review,1998, p242 29 Pamela Pilbeam, ‘Madame Tussaud and the business of wax: marketing to the middle classes’ Business History, 45, 1, 2003 30 Leonore Davidoff, ‘The separation of home and work? Landladies and lodgers in nineteenth and twentieth century England’ in Sandra Burman [ed] Fit work for women 1979 31 For example, Beverly Lemire, ‘Petty pawns and informal lending: gender and the transformation of small-scale credit in England, circa 1600-1800’ in Kristine Bruland and Patrick O’Brien [eds] From family firms to corporate capitalism. Essays in business and industrial history in honour of Peter Mathias, 1998; Judith Spicksley, ‘Was the single woman really marginal? Lending and information networks in seventeenth century England’ paper delivered to the workshop of the Women’s Committee of the Economic History Society, 2003; and Alison Parkinson Kay, ‘A respectable business: women and self-employment in nineteenth century London’, paper delivered to the Economic History Society Conference, Durham, April 2003. Alastair Owens has also contributed to this area of historical enquiry. See forthcoming chapter on ‘Women and investment in nineteenth century Britain; and D R Green and A Owens, ‘Gentlewomanly capitalism? Spinsters, widows and wealth holding in England and Wales c 1800-1860’ Economic History Review, LVI, 3, 2003 32 Nicola Reader ‘Female friendly societies, 1780-1850’ PhD research in progress, School of History, University of Leeds. 33 Stana Nenadic ‘The social shaping of business behaviour in the nineteenth century women’s garment trades’ Journal of social History 1998 34 Stana Nenadic argued, in ‘social shaping…’, that the vast majority of businesses in nineteenth century Britain were small in scale, and unmodernised in their structure and strategy. 35 Robert Bennett, ‘Gendering cultures in business and labour history: marriage bars in clerical employment’ in Margaret Walsh [ed] Working out gender. Perspectives from labour history 1999, p204 36 Ellen Jordan ‘The lady clerks at the Prudential: the beginning of vertical segregation by sex in clerical work in nineteenth century Britain’, Gender and History, 8, 1, 1996 37 Jean Gardiner, Gender, care and economics 1997; and ‘Rethinking self-sufficiency: employment, families and welfare’ Cambridge Journal of Economics, 24, 2000, pp671-89 38 Walby, Gender transformations 39 See, for example, Mary B Rose, ‘Networks, values and business: the evolution of British family forms from the eighteenth to the twentieth century’, Entreprise et Histoire 1999; Jonathan Brown and Mary B Rose [eds] Entrepreneurship, networks and modern business 1993 40 Both Chandler, and Berthof, confirm the masculine nature of business enterprise as an implicit justification for a male approach to business history. Although Chandler’s approach is being increasingly criticised, it continues to underpin the work of many male business historians. 24 16