Dr. N. Mndende

advertisement

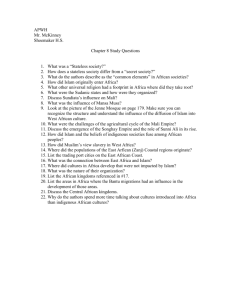

Traditional leadership and governance re-contextualised By Dr Nokuzola Mndende (Director of Icamagu Institute) When I got an invitation to come and speak about the cultural and political perspective of “Traditional Leadership” I first struggled about understanding the actual meaning of the term “Traditional Leadership” and it took time for me to actually get into the core of my topic. I had one barrier which I felt would be a hindrance in expressing my views on the topic, that is to discuss an indigenous way of life in another language outside its own context. Though we cannot help it at present, it will always create problems as there are untranslatable terms which are in most cases either compromised for the sake of common understanding amongst ourselves or are just totally distorted or displaced. Most people prefer discussions in English, not because we have no lingua franca in Africa, but just to appear more civilised as English is perceived by most people as a measure of one’s intelligence, academic level or civilisation. Today I am being asked to come and speak about ‘traditional Leadership and Governance” but I am not yet sure of the context in which the term ‘traditional’ is being used in the present moment. I may be taking you back to something that you may had discussed in your previous conferences but I have to raise it again here so that it is clear to everybody that there are still challenges in the use of the term ‘traditional’ as nowadays the term is, in many cases not used from its original context but has some racial and class connotations. Sometimes the use of ‘traditional’ when it comes to indigenous black people in South Africa, always implies something of the past which is packed somewhere and something that is not capable of change until it is absorbed by the west where the west is always perceived as equivalent to civilization and holiness. When people talk about dynamism they always equate it with the west and its culture as if the west is above times. Unfortunately Africans themselves have accepted that misconception and regard what is theirs as incomplete until it is mixed with something from above the Mediterranean Sea no matter how outdated it is. This causes an identity crisis and mental collision amongst Africans themselves as they have a tendency to justify their actions by first quoting from Europe and then come back home later to endorse their findings. When talking about the Rites of Passage, for example, some people will first quote the French ethnographer Arnold van Gennep and will then come home and discuss initiation. This reversal of approach, which is starting from the unkown to the known, causes confusion even in the cultural practices in our communities. Also the imposed and assumed superiority of the Roman/ Deutsch Law over the indigenous law of the country does not bring any hope in reviving, and adaptations of the indigenous law of the country since the indigenous law is always judged from this foreign law irrespective of the many differences it 1 has in keeping the communal way of life among the communities. Zvabva puts the cause of such an identity crisis to colonization and he says the following: The worst type of colonial enslavement is the cultural spiritual one where the colonised is given a distorted image of himself and of his God by his oppressors and he accepts that image, and continues with it unquestioningly despising himself, his culture and his religion and slavishly aping the culture of his colonisers (Zvabva1991: 76) In this democratic dispensation where there is a general interest in bridging the gap between the previously displaced and manipulated legal system together with the imposed foreign legal system, there were again shortfalls in the process of working towards equality for all. The owners of the manipulated legal system, which is the indigenous law of community life, were not first asked to define themselves and how they would like to get into this wagon of democracy without compromising their roles as custodians of African culture. Some, who were already part of the wagon, were having one foot in their own traditions and another in the foreign traditions, and unfortunately it was/is still the foreign traditions that dictate their incorporation to democracy. The indigenous traditions are regarded as the other and the custodians have to plead for recognition and have to make many adjustments to be incorporated into the status quo, like an inkosi being a Member of Parliament and has to report to the chief whip on his activities during Constituency week, failure to do that may result into a hearing or any other form of discipline. The chief has to obey so as to have food on the table. This approach shows that somewhere somehow an incorrect map had been used to bring equality of these traditions together in a multi-cultural and multi-religious society but the status of an inkosi has been compromised. Chinweizu advises us on how we should approach our history by arguing as follows: A map of our past is the pathfinder to our destiny. Thus if we misread the map of our past or consult an incorrect map, we will misdirect our efforts in shaping our future (Chinweizu, 1987) By having an inkosi reporting to umntu omnyama, clearly shows that culturally and politically, an incorrect map had been consulted. Today it is also difficult for us as people who are not coming from the royal families to know the differences between a ikumkani, inkosi, inkosana, amaphakathi, and isibonda because all of them are under one category of ‘traditional leadership, and sometimes chiefs of a lower status, or headmen, because of their expertise in the Roman-Deutsch Law, they are elected to be the leaders of their seniors. As chiefs are the custodians of African culture or perhaps let me say that they are supposed to be custodians, it will be important for us that in our deliberations in this conference we also take into consideration the history of our past if we want to move forward together, recognizing our unity in diversity. 2 1. Traditional Leadership in context The use of the term ‘Traditional Leadership” , as explained earlier is confusing because it could mean a broader category within the African way of life. Today we hear from the Nhlapo Commission that almost all clans are claiming their historical genealogies as ‘traditional leaders’ irrespective of which house a person was born into, or which level that birthright is in the hierarchy of the royal line. This is because there are several categories in this sphere of ‘traditional leadership’. When one speaks of inkosi/ kgoshi no one from within the indigenous African Culture takes time to think what this is all about, but when one speaks of Traditional leaders, it may mean many things as even myself as umafungwashe (firstborn woman in my clan), I am a traditional leader though I am not an inkosazana from a royal standard. In any clan nothing would be done by the male side without informing umafungwashe as even a ritual done without informing iintombi (females born within the clan) is incomplete and will never be successful from cultural standards. It is unfortunate than in our continent we do not have an indigenous language in which we can communicate because we are now struggling with the use of these untranslatable terms like our indigenous leaders. I think we still need to find out if the use of the term “traditional leader’ to iinkosi zethu is the appropriate term regarding their status and office. I always struggle to accept the use of the term ‘traditional’ as it is now used to put anything indigenous in Africa, like traditional healers, traditional medicine, traditional poets, traditional music, traditional religion, in a lower status as compared to their equivalents globally. Though the term in itself has got no racial connotations but its use in Africa today is wrapped up in racial and class divides. The reasons for my uncertainty is because I have never heard of Prince Charles or the Prince of Paris, or King of Morocco being constantly classified as traditional leaders where ever they go, yet they are the leaders of their respective traditions of their countries. With them the frequent adjective to define them is that of the royal blood. Is traditional synonymous with the indigenous black people of Sub-Saharan Africa? Other examples of this demeaning use of ‘traditional’ is found in many aspects relating to anything indigenous in Africa like herbal medicine. When an herbal medicine is used by an inyanga/ixhwele, it is called a traditional medicine but when the same medicine is used by other races even here in South Africa, it is either called natural or herbal medicine. When our people, for example, pick up an aloe leaf from its habitat it is called a traditional medicine, but when the same aloe is processed in the laboratory and the juice is taken out and dried, it is no longer called traditional but western or modern medicine, but it is the same juice only different instruments are used to extract it. Idowu (1973) in his justification of the use of the term ‘Traditional’ in his understanding of African Traditional Religion, defines ‘traditional’ to mean, 3 Native, indigenous, that which is aboriginal or foundational, handed down from generation to generation, that which continues to be practised by living men and women of today as the religion of the forebears, not only as a heritage from the past, but also that which peoples of today have made theirs by living it and practising it, that which for them connects the past with the present and upon which they base the connection between now and eternity (Idowu, 1973:104). Coming to the office of ‘traditional leadership’ as used to mean royal house, abantwana begazi themselves are not guiding us properly so that we understand their inborn superior status. As traditional leadership is mainly based on the birthright, inkosi iyazalwa ayivotelwa, that is, inkosi is born, he is not voted for his position of leadership. The use of the term traditional leadership to refer to ubukhosi could be confusing if it is applied from a general context. In each clan there are special people who are the leaders in the traditional practices of their communities like, the elderly, inkulu (first born male), umafungwashe, (first born woman), an intlabi (a person who slaughteres animals), some uncles and aunts. When these are classified they fall under the category of traditional leaders without being iinkosi. When there is a family dispute and the case is taken to komkhulu, in most cases inkosi refers the case back to the clan because he knows that each clan has its own traditional leadership. Therefore to be precise in my deliberations here I will not use ‘traditional leadership’ but will use ubukhosi. As I have explained earlier that iinkosi are some of the indigenous leaders and they play a crucial role in looking after the welfare of their communities/tribes, they form the top structures in the political and social welfare of their communities. They lead by example, that is why inkosi cannot or is not supposed to be seen in a tavern for example. Ikomkhulu is the home for everybody that is why no one would hesitate to send any stranger to komkhulu where s/he is to be accommodated. Though ikomkhulu is to accommodate everybody it was not expected for inkosi to leave his culture and adopt the culture of the strangers and sacrifice the culture of the people he is leading. 2. Cultural and Political aspects Former President of the democratic South Africa, uBawo uRholihlahla Mandela in his book, Long Walk To Freedom explains how his father was deposed of his chieftainship because he refused to appear before the magistrate in Mthatha. He puts it as follows: One day one of my father’s subjects lodged a complaint against him involving an ox that had strayed from its owner. The magistrate accordingly sent a message ordering my father to appear before him. When my father received the summons, he sent back the following reply: ‘andizi ndisaqula’ (‘I will not come, I am still girding for battle’)…. 4 My father’s response bespoke his belief that the magistrate had no legitimate power over him. When it came to tribal matters, he was guided not by the laws of the king of England, but by the Thembu custom. This defiance was not a fit of pique, but a matter of principle. He was asserting his traditional prerogative as a chief and was challenging the authority of the magistrate (Mandela1994: 6) This type of response from a chief was one amongst the very few as most of them, because of the pressure had to submit to the rule of the day which was colonialism with its appendages. Because of colonialism, unity in the practice of indigenous customs was broken down as divisions came up amongst the people under these chiefs and within chieftaincy itself. As chiefs were the custodians of African culture, they were supposed to guard against any foreign powers that intend to destroy it as any nation that has lost its culture has no identity, no roots and therefore cannot claim to have indigenous leaders. Because ikomkhulu is the home for all, some chiefs misunderstand that it means that they themselves must leave their traditions and adopt the imported ones and accept the colonial interpretation that African culture is backward, ancient and has no knowledge of the Creator. Most of them were made to believe that God did not speak to their ancestors but only spoke to the people of Israel. This caused divisions even amongst themselves. Today we find chiefs being members of umanyano, something that makes them to be under the guidance of church elders which is the reversal of things. To those who are not part of the new religion there are some concerns of this new junior status of ubukhosi. 3. Divisions The first thing Europe did in the Sub-Saharan Africa was to divide Africans into believers and nonbelievers. To believe was based in believing in the religion that they brought and a non-believer was the one who rejected their form of belief. All the African practices that were contrary to the Christian doctrines were relegated into an outdated African culture and this has caused an identity crisis to those who accepted Christianity and on the other hand also believe in the therapeutic power of African rituals for ancestors and the African way of life in general. Philip Mayer (1971), in his research in the East London area in the early seventies of the 20th century shows that amaXhosa, for instance, were divided into two groups, which were Amaqaba (those who smear ochre) or abantu ababomvu (Red People- because of the ochre), and the second one being called abantu basesikolweni (school people) or amagqobhoka (Christian converts). Mayer further explains the root cause of the divisions as follows 5 A Xhosa asked about the basic differences between Red and School people will often put the acceptance or rejection of Christianity first of all (Mayer 1971: 29) The general characteristic features of Amaqaba as seen by amagqobhoka were that amaqaba are: i) Illiterate, literacy being defined from a western perspective ii) non- progressive iii) living in the past iv) have no knowledge of a true God v) are pagans vi) They were also believed to be very close to nature hence their religion was sometimes called nature religion with secular spirituality. Amagqobhoka on the other hand were and still are understood as: - literate - progressive - sophisticated - have an absolute knowledge of God through his holy word. - will definitely go to heaven as their spirituality goes beyond the grave - have a superior mentality than amaqaba because they know what God wants through his book. These divisions not only affected the ordinary, even the chiefs themselves were divided according to amaqaba and amagqobhoka and this has caused cultural and spiritual differences amongst themselves. Those who were converted believed that Africans never had spirituality but only had a culture. Then these divisions resulted in further categories among the indigenous people and this diluted the practices of African traditions and customs and developed some the mistrusts to some of the chiefs from their communities. In these divisions, what is regarded as the indigenous religion by amaqaba is defined as culture by amagqobhoka and to them (amagqobhoka) religion is equivalent to Christianity. This religious dualism shows that there is a problem of theory and practice which had been imposed upon Africans and unfortunately they accepted it without questioning it. Till today Africans are still trapped within these terminologies and they themselves use them as a tool to divide them and to define the ‘other’. These categories are explained in the following simple drawing 6 A: AFRICAN RELIGION B: BOTH C: CHRISTIANITY The Commission for the Promotion of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities of which I am part of received a complaint from a certain community from one of the provinces. The community members were saying that because their chief belongs to a church which regards Saturday as the holy day and a day of rest, he therefore gave an instruction that no one under his jurisdiction should bury on a Saturday. He told them to bury in any other day except Saturday. That was problematic to both Christians who regard Sunday as their holy day and a day of rest, and to the adherents of African Traditional Religion because Saturday is convenient for them as it is during the weekend. Now the question is which tradition does that ‘traditional leader’ follow? Which tradition is he imposing to his people? On the contrary in another province, the local chief instructed people not to work on Sunday, no ritual performance, no planting allowed on this day because it is a church day. This brings us to question even the origin of this concept of a ‘holy day’ in Africa. 4. Special day of worship is a foreign culture In the African tradition there is no special day of worship. All days were created by the Supernatural Power, the Creator; therefore it is regarded as disrespectful to think of one day as holier than another. This may imply that one day is not holy at all or it is less holy which also implies that the Creator has degrees of holiness from most holy to less holy. All days are the same. For communal worship, people gather together when they are performing rituals, but the day of the ritual is not taken as holier than other days. What is regarded as holy is the ritual itself. There is no formal word in African languages that refers to a regularly reoccurring period of days such as a week either now or in the past. The present use of iveki , in isiXhosa and other languages for instance referring to a ‘week’ is the xhosalising of Afrikaans ‘week’. 7 The names that we use today are the adaptations of the imported concepts and beliefs of other nations who came to the country. The Christian belief that Sunday is the holy day and is the day of rest, and for Monday to be the first day of the week was implanted into the African mind by colonialism and evangelisation. One should also bear in mind that the present naming of the English days of the week is after the Roman goddesses and the gods of the Anglo Saxons. The Romans named the seven days of their week after the sun, moon and five planets. The English names, Sunday and Monday, are also named after the sun and the moon, but from Tuesday to Friday the days are named after the gods of the Anglo Saxons who settled in England about 1 500 years ago. They were related to many groups of people including the Norse people who lived in Norway, Sweden and Finland very long ago. They were called the Teutons. These days were named as follows: Sunday: The old English word was Sunnandaeg, the day sacred to the sun Monday: The word comes from the old English word Monandaeg which means ‘moon’s day’. Tuesday: It comes from Tiu or Tiw, the old English names for Tyr, the Norse god of war, and they called it Tiwensdaeg Wednesday: It comes from the old English Wodnesdaeg. This day gets its name from Woden or Odin, the chief god of all the Teuton people. He was considered to be very powerful. He lived in Valhall, which was a huge hall, glittering with gold, where the people believed great human heroes went after they had died in battle. Thursday: named after the Teuton god, Thor, the god of Thunder. Friday: from old English Frigedaeg, Frigg’s day. Frigg was the Norse goddess of love and Odin’s (Woden’s) wife. Saturday: This comes from the Old English Saeterndae, the day of the planed Saturn, which was named after the Roman god Saturn, originally the god of agriculture. (Stonier, Omar, Mndende, Pillay & Reisenberger; 1996:12) When the missionaries arrived in the early nineteenth century they stressed the importance of Sunday, or “Church Day” (iCawa). Later the working days of the week also became significant and were named in the following manner: Monday – uMvulo – the opening day Tuesday – uLwesibini – the second day 8 Wednesday – uLwesithathu – the fourth day Friday – uLwesihlanu – the fifth day Saturday – uMgqibelo – the finishing day Sunday – iCawa – the church day (also made to be the day of rest) AmaXhosa had a five day sequence of days starting from ‘Namhlanje” which means ‘today’ and were as follows: Namhlanje – today Ngomso - tomorrow or the next day Ngomso omnye – the day after tomorrow Izolo - yesterday Izolo elinye – the day before yesterday Another informal complaint was on uLibo (First fruit ritual) which was performed in the Eastern Cape. The community members were excited when their local chief initiated this nearly forgotten tradition among the Xhosa communities. But what lowered their morale was when the ritual was lead by bishops wearing their church regalia and reading from the Bible. The person who complained had put his concern as follows: I have not heard that the Paul of the Bible came from a royal family, but our chiefs and kings are the subjects of Paul, as a result even here at home chiefs become subjects of priests even if they are not abantwana bagazi. This is confusing because we do not know whether it’s the chief first or Paul’s disciples. Who is above the other in status? To me the status of my chief is above that of Paul and John 5. Death and Life after death The meaning of death in the two religions differ, Christianity claims that the dead are waiting for the Second Coming of Christ in Hades and they have no contact with the living. In African Traditional Religion, death is regarded as a transitionary stage before one can join the departed and enter the world of ancestors. When someone dies s/he is often referred to metaphorically, in the following ways: Akasekho - not longer present Usishiyile - has left us Uhambile - has gone 9 Uswelekile- has become scarce Utshonile/utshabile - has disappeared Death means the physical separation of the flesh from an immortal soul. In African religion, it is believed that although the flesh decays, symbolically the bones are believed to remain alive and have the ability to see, hear, feel and experience a range of emotions. Bones of the deceased are treated with great respect and are believed to have the ability to ‘speak’ (ayathetha) and ‘hear’ (ayeva) when someone is speaking to them. Today there is a burning issue of the shortage of land for burial and people are encouraged to opt for cremation. Because of the belief in ancestors cremation is unAfrican and it is the task of our chiefs to fight against that imposition and to suggest some alternative methods of burying a person. 6. Supremacy of the Roman -Dutch Law over the indigenous law of the land The role of the family and that of chieftaincy have been overshadowed by the foreign laws that do not look at the holistic manner of disputes but are individualistic. Human rights are no longer looked at from a communal way or how they affect other people around but are so individualistic in such a manner that even if they split the family is not such a concern. Some Bills have left the members of the rural communities biting their lower lips and these have not done justice in uniting the families but instead they are bringing them apart even in rural areas when family cohesion should champion. These are Bills like the new children’s act of saying that a girl at the age of twelve can make decisions about contraception without the consent of the parent, the Civil Union Bill and many others. Should such bills be discussed in chief’s inkundla where everybody is given a fair chance to contribute some other resolutions could have been reached without compromising the role of parents. The manner in which rape is dealt with in our communities could be one of the cases that need reference to the chief’s courts where rape was mainly dealt with by women like in Isihewula. New methods could be developed but the majority of decision makers be from the sides of the victimized sex. In many countries the law of the land takes becomes the foundation and whatever is brought in is adapted to go in hand with the indigenous law. Here at home the law of the land is measured in terms of western scholarship. This cultural dependency and black submissiveness to another culture and spirituality has resulted in the diminution of an African identity. Though we are liberated, we still use the west as the measuring rod for our activities. We are always starting from the unknown to the known, instead of vice versa. One could notice that whenever there is a moral debate in South Africa, people will start 10 their arguments by what the Bible says, or what Paul said to the Phillipians or Galatians or Corinthians and never from what our forefathers said to Africans. That is why Chinweizu suggests that in order to move out of this confusion Africans must try to: To shift intellectual gear from what Europe has done to us (How Europe underdeveloped Africa), to what we are doing to ourselves (How Africans maldevelop Africa), and to what we must do for ourselves in order to get out of our condition (How Africans can develop Africa), (Chinweizu, 1987: 73). It will be important, if possible, that the concept of ‘traditional leadership’ be revisited and be explained which law will be the foundation and how it will interact with the other legal systems that are operating globally. Pursuing the proposed Department of ubukhosi would be a great idea only if it will bring to the center the communal way of bringing back unity and morality in our communities 11 REFERENCES p’ Bitek, O. (1970). African Religions in Western Scholarship. Nairobi: African Literature Bureau Chinweizu (1987). Decolonizing the African Mind. Nigeria: Pero Press. Idowu E. Bolaji (1973). African Traditional Religion: A Definition. London: SCM Press LTD Keulder C. (1998). Traditional leaders and Local Government. Pretoria: HSRC Mandela, N. (1994). Long Walk to Freedom. South Africa: Macdonald Purnell (PTY) Ltd Mayer, P. (1971). Townsmen or Tribesmen. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. Mcetywa S A M (1998). Mpondo Heritage: An Expression of Ubuntu. University of Natal: Institute of Black Research/Madiba Publishers. Mndende N (2000). Kutheth’ ithongo. Dutywa: Icamagu Peires J B ed.(1983). Before and After Shaka. Rhodes University: Institute of Social and Economic Research Stonier, J; R. Omar, N. Mndende, S. Pillay & A. Reisenberger (1996): Festivals and Celebrations. Kenwyn: Juta & Co. LTD Zvabva, O. (1991). “Development of Research in African Traditional Religions”. In S. Nondo (ed) Multifaith Issues and Approaches in Religious Education with special reference to Zimbabwe. Utrecht: Rijksuniversiteit. 12