Qudrat Ullah v. Bareilly Municipality A Case Review

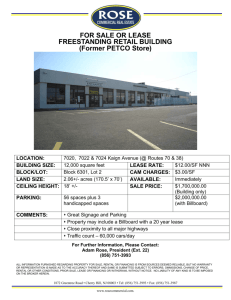

advertisement

Qudrat Ullah v. Bareilly Municipality A Case Review 1 Table of Contents Table of Cases ......... 3 The Facts of the Matter ......... 4 Research Methodology ......... 7 Judicial Appreciation: The Decisions of the Courts ……9 The Courts and the Distinction : A chronological evaluation of case law till Qudrat Ullah The Decision in Qudrat Ullah and it’s Impact Beyond Qudrat Ullah Explaining the Determinants ……18 In Conclusion ........20 Bibliography ........22 2 Table of Cases Acting Secretary, Board of Revenue v. The Agent, South Indian Raliway Co Ltd., AIR 1925 Mad 434 (Full Bench). Antoniades v. Villiers, [1988] 3 All E.R. 1058. Associated Hotels of India Ltd. v. R.N. Kapoor, AIR 1959 SC 1262. Booker v. Palmer, [1942] 2 All E.R. 674. Cobb v. Lane, [1952] 1 All E.R. 1199. Doe d. Tomes v. Chamberlaine, (1839), 151 E.R. 973. Errington v. Errington, [1952] 1 All E.R. 149. Cariappa v. Leila Roy, AIR 1984 Cal. 105. Hindustan Steel Ltd v. Kalyani Bannerjee, AIR 1973 SC 408. Inwards v. Baker, [1965] 1 All E.R. 446 (Court of Appeals). Khalil Ahmed v. Tufelhussein, AIR 1988 SC 184. Lynes v. Smith, [1899] 1 Q.B. 486. Ministry of Health v. Bellotti, [1944] 2 All E.R. 674 Mrs M.N. Clubwala v. Fida Hussain, AIR 1965 SC 610. Peakin v. Peakin (1895), 2 I.R. 359. Puran Singh Sahni v. Sundari Bhagwandas Kriplani , (1991) 2 SCC 180. Qudrat Ullah v. Municipal Board, Bareilly, AIR 1974 SC 396. Revenue Board v. A.M. Ansari, AIR 1976 SC 1813. Shyam Sundar Ganeriwala v. Delta International Ltd., AIR 1998 Cal 233 Sohan Lal Naraindas v. Laxmidas Raghunath Gadit, (1971) 1 SCC 276. Southgate Burrough Council v. Watson, [1944] 1 All E.R. 603. Sridhar Suar v. Jagannath Temple, AIR 1976 SC 1860. Stinson v. Hardy, 27 Or. 584. Swarn Singh v. Madan Singh, 1995 Supp (1) SCC 306. Tarakeshwar Sio Thakur v. B.D. Dey, AIR 1979 SC 1669. 3 Qudrat Ullah v. Municipal Board, Bareilly The Facts of the Matter Justice Krishna Iyer opened the verse of his judgement in Qudrat Ullah v. Municipal Board, Bareilly by pointing out that though the crux of the judicial determination in this matter was merely the construction of contract, justice had been delayed for almost 24 years. The judgement in Qudrat Ullah brings to light one important fact, being that despite almost 50 years of judicial debate on the subject of the telling of a lease from a license the law in that area was far from settled (the first notable Indian case being Acting Secretary, Board of Revenue v. The Agent, South Indian Raliway Co Ltd 1). In the case under review the defendant (the appellant’s father) had for several years been collecting “tahbazari” dues from shops and sheds in a market in Patelganj, Bareilli under contracts from the Municipal Board, Bareilly. The last of such contracts was executed on 19-11-1944. The defendant contested that a fresh contract came into existence on 31-12-1947. The plaintiff contrarily contested that this contract had not acquired binding nature and followed this up in a suit demanding that absolute possession of all the properties over which due was realised be restored to the plaintiff. The question with regard to the existence of the fresh contract was decided affirmatively and the contract was taken as matter not in controversy. The question that then again reared it’s head before the court was whether the deed in question (that being the series of contracts) was a grant of license or a contract of lease since if it was a contract of lease then the defendant/appellant could claim protection under the U.P. (Temporary ) Control of Rent and Eviction Act, 1947. The respondent/plaintiff additionally pleaded that the 1947 Act had been repealed by the Uttar Pradesh Urban Buildings (Regulation of Letting, Rent and Eviction) Act, 1972 and that even if the deed was a decree the appellant/defendant could still be evicted. In the Trial Court it was held that both the earlier and later contract were contracts of lease and the matter being within the purview of the 1947 Rent Control Law the suit was dismissed. The High Court came to the conclusion that both the contracts were composite deeds in the sense that they were leases where the property in question was the shops and sheds but were licenses as far as the footpaths adjoining the roads were concerned. The 4 reasoning of the High Court was that a pavement cannot be said to be an accommodation within the meaning of Section 2 of the Rent Control and Eviction Act of the 1947 Act and therefore the deed was a license with regard to the pavements and a lease with regard to the shops and sheds. The Court adjusted the monetary relief in accordance with the determination. Thus to the limited extent of the patris and pavements possessory relief was given to the plaintiffs (now respondents). The matter then came up before the Supreme Court for consideration. The question that came arose was whether the deed was a lease or a license and also ancillary was the question of the applicability of the 1972 Act. 1 5 Research Methodology Since this a case review the author has attempted not to deviate too much from the case at hand. The emphasis is on the dictate of the case but since the case is embodied in the well developed jurisprudence of the distinction of a lease from a license some independent study had to be pursued as well. In this review all notable Supreme Court cases from 1925 to 1998 have been incorporated to illustrate the law before Qudrat Ullah and the law after it. In the end an effort has been made to succinctly sum up the concepts referred to in the cases to dispel any unclarity. The methodology employed is case review oriented with the whole paper centered on the judgement in Qudrat Ullah. The question relating to Repeal of Enactments has been given second priority to the determination of a Lease from a License. The object of this paper is to review the case in light of existing and following jurisprudence and it’s obvious limitation is it’s being a case review and not a subject review. The Chapterisation is as follows: Chapter 1 which is the Introduction lays out the facts of the case and the main questions involved. Chapter 2 looks at the law laid down by Courts prior to Qudrat Ullah as well as notable British decisions on the point. Chapter 3 examines the decision in Qudrat Ullah specifically. Chapter 4 looks at the decisions following Qudrat Ullah and latest judgements of the Supreme Court on the point. Chapter 5 summarises the factors for determination. Chapter 6 concludes the review by examining relevant concepts involved in the Determination of a Lease from a License. The manner of footnoting employed is standard and uniformly used throughout. It is as follows; BOOK > Authors surname, Authors name, Name of Book, Volume, Edition, Publisher : Publishing Place, Year, Page no. ARTICLE > Authors surname, Authors name, “Name of Article”,Standard Citation of Journal . 6 The Courts and the Distinction : A chronological evaluation of case law till Qudrat Ullah The decision in Qudrat Ullah did stress on the importance of the test of operative intention but it was only one in the long list of notable cases evolving tests for telling a lease from a license. As far back as in 1925 a full bench of the Madras High Court in Acting Secretary, Board of Revenue v. The Agent, South Indian Raliway Co Ltd.,2 considered the distinction between lease and license. In this case coal merchants were given permisiion to stack coal on plots of land belonging to the Railway company. This agreement was stamped as a lease. The court observed that the essential difference between a lease and license is that in the case of the former there is a transfer of interest in favour of the lessee (the person to whom the lease is granted).3 As to how it could be determined that a transfer of interest was made, the court said that one of the primary considerations was a right to exclusive possession. The court stated that “if the effect of the document is to give the holder an exclusive right of occupation of the land, it will be a demise of the land in the form of a lease.” The effect of the document was to be determined by looking at the substance of the deed and not laying too much emphasis on the words used. The circumstances surrounding the transaction and substance of the deed have to be used to determine the intention of the parties. In this case the grantor had mentioned in the deed that “he would have free access to the land at all times” and that “he could re-take the land at any time.” Further more the grantee did not have the “right to sublet the land or to transfer any rights.” The court came to the conclusion that the grantee had in no way a right to exclusive occupation and thus possession of the land and that there was no transfer of property interests. The only transfer was of the usufractory right to stack coal. The decision in this Madras High Court case set the foundations for future determinations by laying down specific criterion. 2 AIR 1925 Mad 434 (Full Bench). This transfer of property interest condition is evident not just in the definition of lease under s.105 of the Transfer of Property act but is also the subject of much case law. See also Mitra B.B., Transfer of Property Act, 16th Edn., Kamal Law House: Calcutta, 1996, p.929; Beg, M.H. and Verma S.K.,Gours’ Law of Transfer of Property, 9th Edn., Delhi Law House; Delhi, 1996, p.1482; Katiyar, B.B., Law of Easements and Licences in India, 10th Edn., Law Book Co.: Allahabad, 1984, p.844; Shukla, S.N., The Transfer of Property Act, 22nd Edn., Allahabad Law Agency: Faridabad, 1998, p.315; Tiwari, H.N., The Transfer of Property Act, Allahabad Law Agency; Allahabad, 1989, p.369. 3 7 One of the issues deliberated briefly upon by the Madras High Court was regarding the matter of exclusive possession. It must be mentioned that even the Madras High Court centered its arguments around exclusive occupation (note the underlined statement which holds exclusive occupation as being conclusive). Previous decisions in English law in Doe d. Tomes v. Chamberlaine4, Lynes v. Smith5, Peakin v. Peakin6 had yielded forth the conclusion that the test of exclusive possession was decisive in determining the status of a transaction as either lease or license. However Lord Denning is his judgement in Errington v. Errington7 dismissed the test of exclusive possession as decisive. He cited the case of Booker v. Palmer8 where an owner gave some evacuees permission to stay in a cottage for the duration of the war. In that case though the evacuees had exclusive occupation the court speaking through Lord Greene holding the evacuees to be licensees and not tenants, observed that “to suggest there is an intention there to create a relationship of landlord and tenant appears to me to be quite impossible. There is one golden rule which is of very general application, namely, that the law does not impute intention to enter into legal relationships where the circumstances and the conduct of the parties negative any intention of the kind.” Lord Denning after citing Booker v. Palmer with approval cited several cases where people with exclusive possession were not held to be tenants(lessees). 9 He then concluded that although a person who is let into exclusive possession is, prima facie, to be considered a tenant, nevertheless he will not be held to be so, if the circumstances negative any intention to create a tenancy. 10 So circumstances may be looked at independently of any exclusive possession seemingly granted. Lord Dennings decision is best substantiated with the example of the need for exclusive possession of the land to do more efficiently the thing for which the license is given. For instance if a landlord says that for three days you can pluck mangoes from my land and in order that no one disturbs you you can have exclusive occupation. Does it mean that a tenancy is created? Does it mean that there is any interest in the land? No! Not necessarily. 4 (1839), 151 E.R. 973. [1899] 1 Q.B. 486. 6 (1895) 2 I.R. 359. 7 [1952] 1 All E.R. 149. 8 [1942] 2 All E.R. 674. 9 Ministry of Health v. Bellotti, [1944] 2 All E.R. 674; Southgate Burrough Council v. Watson, [1944] 1 All E.R. 603. 10 Prima Facie inference to be drawn; This was used in several Indian cases afterwards and has become a general accepted rule. 5 8 Exclusive Possession v. Exclusive Occupation At this juncture it is felt that the Errington thesis is best explained if we understand possession as different from mere occupation. While every license to do an act upon land involves the exclusive occupation of the land by the licensee so far as is necessary to do the act, and no further, a lease does more; it gives the right of possession of the land, and the exclusive possession of it for all purposes not prohibited by its terms. 11 Thus an important distinction is to be made between mere exclusive occupation and possession, the distinction being that while occupation is a single right in itself possession carries with it another bundle of rights. So occupation can be considered to be a single right within possession. In Associated Hotels of India Ltd. v. R.N. Kapoor12 the Supreme Court of India held that there were marked distinctions between a lease and a license and considered the following propositions a) whether a document creates a lease or license, the substance of the document must be preferred to the form; b) the test is the intention of the parties; c) if the document creates an interest in the property it is a lease, but if it only permits another to make use of the property on which legal possession continues with the owner it is a license; and d) if under the document the transferee gets exclusive possession of the property he is prima facie a tenant, but circumstances may be established which negative the intention to create a lease. (So circumstances must be explored before that exclusive occupation is translated into exclusive possession) After the decision in R.N. Kapoor the importance of intention was stressed upon and this gave rise to new rush of jurisprudence on the subject of this test of operative intention. “Note: Status as licensee or lesse of one in occupation of land in anticipation of the making or execution of the lease”, 123 A.L.R. 700. 12 AIR 1959 SC 1262. 11 9 The Test of Operative Intention and the Decision in Qudrat Ullah In 1971 in Sohan Lal Naraindas v. Laxmidas Raghunath Gadit 13 , the Supreme Court deliberated on the issue again. The plaintiff had granted the use and occupation of a loft to the defendant. Some of the relevant conditions were that the “licensee” shall use and occupy the said loft as a cloth merchant only and will not carry on any other business and that the grantee had no right as a tenant or sub-tenant. The Supreme Court held that a prima facie inference of tenancy could be drawn from the fact that there was exclusive possession. They also stated that the agreement though in substance one of lease was masked by clauses such as the one denying tenancy and the one barring the practice of any other trade. They found no circumstances to negate the exclusive possession inference and came to the decision that an interest had been conferred granting use and occupation. Thus the intention of the parties was to create a lease and mask it as a license. The Court reaffirmed a prior decision in Mrs M.N. Clubwala v. Fida Hussain14, where it was held that though there is no simple litmus test to distinguish a lease from a license the character of the transaction turns on the operative intent of the parties. Thus at the time when the Supreme Court adjudicated in the Qudrat Ullah matter the test of operative intention was not alien to it. The Court in Qudrat Ullah quoted extensively from the decision in the Associated Hotels case and well as the British law enunciated by Halsbury. It accepted the exclusive possession hypothesis unanimously forwarded by previous decisions. The Court dwelt on clauses 1,2 and 4 of the contracts whereby it was stated; “During the entire period of theka, the first party shall have all the rights and powers, as per conditions laid down in the auction sale and agreement in respect of use of sheds and shops as enjoyed by the second party as proprietor in possession of the said property.” “The first party shall have possession of the sheds aforesaid detailed in the said map and 11 shops aforesaid.” “In all the eleven shops included in the Theka, I, the Thakedar would be empowered to let them to the sub tenants on rents mutually settled between us.” 13 14 (1971) 1 SCC 276. AIR 1965 SC 610. 10 The Court stated that these clauses strongly suggested the inference that the deed was a lease by way of conference of absolute possession. On being brought to the notice of the court that the Board had certain regulations and controls vested in it the Court re-emphasised that even if the deed contained certain restrictions on exclusive possession that by itself did not diminish the character of the deed from lease to license. The question then arose as to whether the deed was a composite one in the sense that though a part of it was lease another part merely conferred a license. On reviewing the deed the Court observed that although the demise of the pathways might cause public inconvenience, as long as the Board had the powers to transfer interest in them one would still have to rely on the construction of the deed. The Court then pointed out that the deed made no differentiation between the pathways or patris and the shops and sheds. In fact the deed contained exception recitals such as “the thekedar will have no objection to the municipality constructing iron gates” indicate that the thekadar had exclusive possession characteristic of a leasee. Thus the Court held that the contract conferred lease-hold interest and that merely the fact that the footpath were used by the public did not dilute the demise to a license and take away it’s original character. Then the Court turned to the question of whether the patris and pathways could be considered to be accommodation within the meaning of the rent control provisions. In response to this it was pointed out that though the deed was a lease deed even then possession of some of the property leased would not come within the protection of the rent control act since it would not amount to “accommodation”. The Court observed that the pathways and patris though part of the leasehold interest was property falling out of the definition of “accommodation” and thus the appellant could not avail of protection for the same under the rent control provisions. Thus in regard to the primary issue the Court held that though the deeds were leases with regard to the pathways and patris the appellant could not avail of protection under the Rent Control Act. The Court placed it’s reliance on the dictum that if the Municipal Board had the power to lease out the patris and pathways and if it substantially intended to do so at the time of the transaction then it could not deny the same at this stage in order to take away any accruing rights of the appellant / lessee. The Court then decided on the ancillary issue of applicability of the 1972 Act. Application of the UP Urban Buildings (Regulation of Letting, Rent and Eviction) Act, 1972. 11 The question that arose before the Court on this issue was whether the appellant had rights as a tenant under the 1947 Act and whether this right was preserved and unaffected under the 1972 Act. In this context the appellant contended the applicability of s.6 of the U.P. General Clauses Act which states that any rights accruing under an earlier Act will not be affected by a later Act unless the late Act expresses a contrary intention. The Court held that even if the appellant could be said to have a right under the earlier Act s.6 of the U.P. GCA would only save that right if their was no contrary intention expressed under the later Act. The same principle was laid down by the Supreme Court in Indira Sohanlal v. Custodian of Excise Property, Delhi 15 . In the matter at hand the Supreme Court felt that the later UP Act of 1972 expressed contrary intentions in Sections such as 43(2)(h) where parties were allowed to amend their pleadings in proceedings carrying on at the time of the new enactment. Thus, there seemed to be the intention to extinguish previous rights and liabilities. The Court thus held that s.6 of the U.P.GCA would not apply to this matter and that the new Act would apply thus extinguishing the rights of the appellant in that regard. 15 AIR 1956 SC 77. 12 Beyond Qudrat Ullah Qudrat Ullah did in no way put an end to agitation on the distinction between lease and license. The Supreme took up the matter again in numerous subsequent cases and invoked different tests to determine fact based problems. In Revenue Board v. A.M. Ansari16 the Supreme Court followed the path set in R.N. Kapoor and Qudrat Ullah by working on the same propositions. They asked the same question asked by Denning in Cobb v. Lane17, “Did the circumstances and the conduct of the parties show that all that was intended was that the occupier should have personal privilege with no interest in the land?” The court then considered the salient features of the agreement such as the short duration of nine to ten months and use of the land for merely cutting the fruits on the trees. The conclusion reached was that the agreement was a license and not a lease. In another case that followed in the same year, Sridhar Suar v. Sri Jagannath Temple18, similar legalese as used to declare an agreement as license since it granted the land for a specific purpose for a short duration. The Supreme Court in Tarakeshwar Sio Thakur v. B.D. Dey19 also stated that exclusive possession subject to certain restrictions may still constitute a lease. In a notable decision of the Calcutta High Court in G. Cariappa v. Mrs Leila Sinha Roy20, besides reaffirming previous decisions of the Supreme Court the court also pointed out that calling of any payment as rent is not conclusive as tenancy. In Khalil Ahmed v. Tufelhussein21, the Supreme Court used the test of manifest intention and stated that in the matter at hand the property was to be used for specific business purposes and also noted that there were several restrictions on the use (such as the right to enter upon the premises and inspect the same at any time) which negatived any conclusion of exclusive possession/interest in the property. The deed was held to be a license. 16 AIR 1976 SC 1813. [1952] 1 All E.R. 1199. 18 AIR 1976 SC 1860. 19 AIR 1979 SC 1669. 20 AIR 1984 Cal. 105. 21 AIR 1988 SC 184. 17 13 Masking clauses22 and the decision in Antoniades v. Villiers23 In 1988 which was the same year the Supreme Court delivered a judgement in Tufelhussein the House of Lords gave a judgement in the matter of Antoniades v. Villiers. In that case the respondent let a flat to the appellants, a young unmarried couple, under separate but identical agreements termed licences. The deeds emphasized no exclusive possession. The court held that the true nature of the agreement was to create a joint tenancy since the licensees were husband and wife and the efforts of the landlord through clauses such as the above was to prevent the grantees (husband and wife) protection under the rent acts which tenants are entitled to. It held clauses like the one incorporating the right to enter any time and introduce third parties as being smoke-screen clauses to mask the agreement as license. This also stressed the need to read agreements in whole substance and understand the nature of negative covenants. The Court in Qudrat Ullah had made an indirect reference to such a tendency of land owners to mask demises as leases to maintain a greater amount of control over the property interest. The Invocation of Ex Praecidentibus Et Consequentibus Optima Bit Interpretatio and the decision in Puran Singh Sahni v. Sundari Bhagwandas Kriplani24 In 1991 in the above mentioned case the Supreme Court besides deliberating on other issues regarding the determination of lease or license considered elaborately the question of circumstances surrounding the formation of the deed, the maxim being ex praecidentibus et consequentibus optima bit interpretatio 25 . The maxim meant that while interpreting the agreement we also have to see what transpired before and after the agreement. The best interpretation is made from the context. As previously held the parties intention lies in the substance and not in the label. If the substance is still unclear then the maxim comes into play. It must be noted that the doctrine was invoked in substance though not in name in several prior cases including Qudrat Ullah when the Court through Krishan Iyer referred to the laws of England as laid down by Halsbury. In Puran Singh Sahni’s case the court held the agreement to be a license since the grantee was given a furnished flat purely for temporary occupation and no interest was given in the property. The grantor never made an attempt to or authorised any persons to use the Also see with regard to de-facto joint tenancy (talked of in conclusion) Hill, Jonathan, “Shared Accomodation and Exclusive Possession”, 52 Modern L.R. 408 (1989). 23 [1988] 3 All E.R. 1058. 24 (1991) 2 SCC 180. 25 Mitra, B.B., Transfer of Property Act, 16th Edn., Kamal Law House; Calcutta, 1996, p. 936. 22 14 rooms along with the couple. This clearly showed that he intended possession to be with the couple but wanted to label the agreement as a license in the eyes of the law. In Hindustan Steel Ltd v. Kalyani Bannerjee26, the Supreme Court held that where the terms of a lease are not free from ambiguity, the conduct of the parties is to be taken into account for determining the true nature of the lease. The last notable case where a question of determination arose was Swarn Singh v. Madan Singh (1995)27. In this case an argument was raised that the inclusion of a clause such as “I shall not further sublet it to anybody else” constituted an effort to convert the agreement of lease to one of license. The Apex Court dismissed the argument giving the folllowing reasonsa) The nomenclature of the document is license though they admitted that nomenclature is not always conclusive; and b) The document in question in no unambiguous terms says that the possession and control shall remain with the owner. This is a clear indication of the fact that no interest in immovable property has been conferred on the grantee. If it were a case under s.105 of the Transfer of Property Act, there must be an interest in the immovable property. On thr contrary if it were to be a license under s.52 of the Indian Easements Act, no such interest in immovable property is created They held the clause that “I shall not sublet it further to anybody else” as being an affirmation of the requirement that only the licensee must use it. The observations in Swarn Singh v. Madan Singh did not offer any great suggestions towards future determinations. It offered a rather simplistic legalese towards the decision The last notable case on the point is Shyam Sundar Ganeriwala v. Delta International Ltd.28 In this decision of the Calcutta High Court the court used the presence of clauses like the one granting the grantee the right to make repairs and add things as evidence of a interest in the land and thus indicative of a lease. 26 AIR 1973 SC 408. 1995 Supp (1) SCC 306. 28 AIR 1998 Cal 233. 27 15 Explaining the Determinants So what is the judicial pronouncement on the issue? The decisions of the courts in cases such as Qudrat Ullah have constituted a process of filtering the law and criterion for determination but have hardly suggested any additional criterion. It is to be noted that none of the tests used in Qudrat Ullah were in any way novel. Over a period of time some factors have emerged and been used to hold agreements as leases and not licenses. Some of those area) Exclusive possession of the premises; b) The opposite party had no access to the portion of the premises occupied by the person in possession; c) The portion occupied by the person in possession was provided with a sub-meter for electricity; d) The monthly payment though termed as “compensation and commission” was in reality rent for the premises occupied by the person in possession; e) The demise was form a fixed term of five years;29 So these considerations were used to distinguish a mere usufractory right from a transfer of interest. It is also to be noted that there are some clear differences such asa) A lease is assignable (a tenant can sublet) while a licence is an individual privilege which cannot be assigned; b) A lease cannot be revoked until the end of its term but a licence can be revoked at will (the situation in the case of a contractual license is slightly different); and c) A lessee can sue a trespasser in his own name but a licensee cannot do so. Finally, the distinguishing criterion established by the various decisions; 1) Transfer of Interest; 2) Exclusive Possession (factors like duration of deed are considered); 3) Substance of the Deed; 4) Intention derived from the substance; and 5) Behaviour of Parties before and after the deed. What emerges finally is the equation 29 Abichandani, K.N., Mulla on The Transfer of Property Act, 8th Edn., N.M. Tripathi: Bombay, 1995 , p.798. 16 LEASE = LICENCE + SOME OTHER RIGHTS Even in Qudrat Ullah reaffirmed the correctness of the equation above by suggesting the unilateral non-exclusive nature of lease and license. The fact of a mere license negates the fact of a lease but the fact of a lease only reaffirms that of an accompanying license. In Conclusion 17 Though in theory there are several differences between a grant of lease and a grant of license all these arise post-differentiation in the sense that only after you determine whether something is a lease or a license can you attach the special characteristics. Thus when the adjudicator gets a piece of paper to adjudge as a lease or a license the choice can a be a tough one to make in practice. It’s interesting to note that while Courts have oft talked about the concept of interest in property they have seldom defined it. Property interest is not just rights on and off the land but rights in the land. This is where the contribution of American case law is appreciable. In a brilliant decision of the Oregon Circuit Court in Stinson v. Hardy30 it was held that lease is a corporeal and a licence an incorporeal heriditament.31 The reason it is submitted why it is so brilliant because it clearly elucidates that in licences the land is a mere via media for a purpose while in the case of a lease it is rights in the property which are transfered. Property interests include rights to sublet, make changes etc. Taking a cue from this we can say that the clause in the contract in the case of Qudrat Ullah which allowed the appellant to sub-let the property was a good indicator of a transfer of interest. As mentioned in the previous chapter the Courts now look to a variety of determinants to make the distinction between a lease and a license. Whether a deed transfers interest or confers exclusive possession is not something which can be determined straightaway, these are things to be inferred from the terms of the contract. Thus it is the construction of the terms which is critical and must be concentrated upon while making the distinction. In my opinion whatever little confusion there has been in this area is because of the reasoning offered by the judges in the notable cases. The emphasis is on post-determination characteristics than on the face-of-the-deed characteristics. It’s almost like if someone asks a person what’s the difference between a lease and a license that person says that lease is defined in s.106 of the Transfer of Property Act and license under s.52 under the Easements Act. Only when one knows the nature of the document can he assign it to a category. Surprisingly, the decision in Qudrat Ullah is fairly straight to the point and concise too. The Court has not gone around in circles but emphasised the need to resolve disputes speedily. Though Qudrat Ullah is says not a epic judgement in the matter it dealt with it should be admired for it’s attitude towards such dispute resolution and it’s concise and specific adjudication upon the contested issue. 30 31 27 Or. 584. 51C Corpus Juris Secundum, p.526. 18 19 A Bibliography Articles “Note: Status as licensee or lesse of one in occupation of land in anticipation of the making or execution of the lease”, 123 A.L.R. 700. Baker, P.V., “Elusive Exclusive Possession”,104 L.Q.R. 173. Barton, J.L., “Concurrent Licensees”, 106 L.Q.R. 215. Hill, Jonathan, “Shared Accomodation and Exclusive Possession”, 52 Modern L.R. 408 (1989). Radin, “Property and Personhood”, 40 Stan. L. Rev. 957 (1982). Sparkes, Peter, “Leasehold Terms and Contractual Licensees”, 104 L.Q.R. 175. Underkuffer, Laura S., “On Property : An Essay”, 100 Yale L.J. 127 (1990). Vajifdar, K.C., “Disputing Landlord’s Title”, Lex Et Juris, Oct 1988. Vajifdar, K.C., “Ensuring Flat Recovery”, Lex Et Juris, August 1988. Vajifdar, K.C., “No Justice for Landlords”, Lex Et Juris, May 1988. Vajifdar, K.C., “Revive Leave and Licence”, Lex Et Juris, Aug 1986. Books Abichandani, K.N., Mulla on The Transfer of Property Act, 8th Edn., N.M. Tripathi: Bombay, 1995. Beg, M.H. and Verma S.K.,Gours’ Law of Transfer of Property, 9th Edn., Delhi Law House; Delhi, 1996. Harwood, Michael, English Land Law, Sweet and Maxwell: London, 1975. Houghton, John and Dennis, Artis, Land Law, 4th Edn., Blackstone Press Ltd.: London, 1985. Katiyar, B.B., Law of Easements and Licences in India, 10th Edn., Law Book Co.: Allahabad, 1984. Mitra B.B., Transfer of Property Act, 16th Edn., Kamal Law House: Calcutta, 1996. 20 Mukherjee, Radharomon, History and Incidents of Occupancy Right, Neeraj Delhi, 1919. Penner, J.E., The Idea of Property in Law, Clarendon Press: London, 1997. Shukla, S.N., The Transfer of Property Act, 22nd Edn., Allahabad Law Agency: Faridabad, 1998. Tiwari, H.N., The Transfer of Property Act, Allahabad Law Agency; Allahabad, 1989. Digests and Reports Law Commission of India, 17th Report (1977) 51C Corpus Juris Secundum. Am Jur 2d Halsbury’s Laws of England, Lord Hailsham Edition, Vol 27. Refered Statutes The Transfer of Property Act, 1882. The Indian Easements Act, 1882. 21 Pub House: