Kathleen Tilly mind mapping letter

advertisement

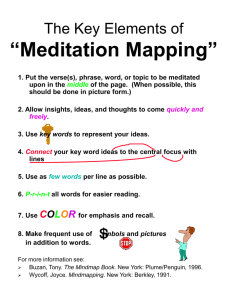

Dear Principal Keene, Over the course of the summer, I was busy finishing my Master’s of Education degree at OISE. One of the many ideas that I took from this experience was a broader understanding of literacy. Prior to my experience at OISE, I, like many teachers, understood literacy to solely include traditional forms of reading, writing and oral communication. However, at OISE I was introduced to the concept of multiliteracies. Multiliteracy instruction replaces traditional notions of literacy with a broader definition, which includes multiple modes of communication, such as spoken, gestured, visual, electronic and graphic forms (Rowsell, Kosnik & Beck, 2008). During my course, I became very excited by the prospect of integrating multiliteracies into my upcoming Grade 4 class. One of the ways that I would like to do this is though electronic mind mapping. In this letter, I will highlight why electronic mind mapping would be a beneficial addition to the Grade 4 program in my class. What are mind maps? Mind mapping was first developed by Tony Buzan, who posed it as a technique for note-taking (Buzan, n.d.). The function of mind maps has since expanded to include: summarizing ideas, making connections between key concepts, consolidating learning, and brainstorming. The graphic organization of information on a mind map is formatted as follows: first, an image representing the main idea is drawn on the center of the paper (Budd, 2004, p. 35-46). Second, thick branches in varying colours are drawn, which flow out of the main idea. Then, key words or images that are associated with the central idea rest on each branch. Since mind maps require students to distill their thinking into single images or key words, they learn to be concise and succinct. Third, less important items within each category are depicted on thinner branches, which grow out from the thicker branches. This format is free-flowing, organized and coherent (Budd, 2004, p. 35-46). 1 Why mind maps are effective Brinkmann (2003) maintains that mind mapping is effective because it simultaneously employs the left and right sides of the brain. Brinkmann (2003) explains, The method of mind mapping takes into account that the two halves of the human brain are performing different tasks. While the left side is mainly responsible for logic, words, arithmetic, linearity, sequences, analysis, lists, the right side of the brain mainly performs tasks like multidimensionality, imagination, emotion, colour, rhythm, shapes, geometry, synthesis (p. 2). According to Brinkmann (2003), when both sides of the brain work in concert, productivity, memory retention, organizational skills, and creativity increase. General benefits of mind mapping First, mind mapping could act as a vehicle for my Grade 4 students to use their knowledge to make connections between concepts and ideas. Making these types of connections is a crucial component of the Grade 4 curriculum. As stated in the Grade 4 Ontario Language Arts Curriculum (2006), students are required to make “connections within and between various contexts (e.g., between the text and personal knowledge or experience, other texts, and the world outside the school; between disciplines)” (p. 19). Mind mapping facilitates students’ abilities to make connections between concepts and contexts. Second, mind maps will encourage my students to organize and summarize information in ways that are meaningful to them. I believe that mind maps are more student-centered than other visual tools and graphic organizers because they are not rigidly structured. As a result, my students can organize concepts on a mind map in ways that are personally meaningful to them, thus increasing their ability to remember and internalize information. Third, I believe that mind mapping would foster creativity among my students. Mind maps utilize two modes, texts and images, which allow students to represent key concepts creatively. Brinkmann (2003) describes the creativity involved in mind mapping as follows: “Artistic arrangements are not only allowed but desired as advantageous. This leads to a gain in creativity and moreover gives great pleasure” (p. 40). Brinkmann (2003) argues that since students are able to express themselves 2 creatively and openly through mind mapping, their interest in, and attitude towards, learning increases. Thus, incorporating mind maps should greatly benefit those students who are visual or kinesthetic learners. Fourth, mind maps fit into my holistic approach to teaching and learning because ideas and concepts on mind maps are non-linear and interconnected; rather than compartmentalized. Brinkmann (2003) explains why mind maps are holistic: “As mind maps have an open structure, one may just let one's thoughts flow; every produced idea may be integrated in the mind map by relating it to already recorded ideas” (p. 39). The interconnectedness of ideas will allow students to see the ‘whole picture’ surrounding a concept (Budd, 2004, 35-46). Benefits of electronic mind mapping As outlined above, there are four key benefits of using mind maps in a classroom. However, the integration of mind maps with technology would have the most profound results for student achievement and understanding. Luckily, we live in a time where this is possible. When Tony Buzan first introduced mind mapping in late 1960s, he implored people to use paper, pencils and markers to create their maps (Buzan, n.d.). However, in our current educational environment, using electronic mind mapping programs such as Inspiration and MindMeister are even more beneficial for promoting student engagement and interest. Inspiration is a digital program that is designed for students ages 9 and up (Inspiration, 2009). MindMeister is similar to Inspiration, except it is webbased (Meisterlabs, 2009). Computer programs, such as Inspiration and MindMeister, are effective electronic mind mapping tools because they elaborate on traditional mind maps by incorporating additional modes of communication. In addition to including text and images, electronic mind maps introduce the possibility for students to utilize video and audio information. Tierney, Bond and Bresler (2006) cite the benefits of multimodal literacies: “multimodal possibilities contribute to learning opportunities in ways that 3 support complex and collaborative engagement with problems and issues, projects and topics, process and product, inquiry and discussion” (p. 3). Clearly, the integration of multimodalities into electronic mind maps makes them more interactive and engaging for students. Another reason why electronic mind mapping is beneficial is because it is portable. Web-based mind mapping tools, such as MindMeister, allow the class to work on mind maps on any computer that is connected to the Internet. Therefore, my students will be able to work on their mind maps in the classroom, in the school’s computer lab or at home (Adam & Mowers, 2007, p. 24). Furthermore, when students create mind maps online through the Internet, collaboration is easier. For example, several students can work on the same mind map simultaneously. Adam and Mowers (2007) explain this phenomenon: Multiple users can access and edit a mind map at the same time. Most applications provide tools for real-time communication and log the changes made by each user. Thus, students working in groups can share their ideas without having to wait for their "turn." Because one document is shared via the Web, users no longer have to worry about which version is the most current” (p. 24). MindMeister will provide my students with the opportunity to create mind maps with other students in different schools and even in different countries! Importantly, electronic mind mapping is also less time-consuming for students. Since mind maps are heavily image-based, when students create traditional paper and pencil mind maps, they often take a very long time. In my previous classes when I asked my students to create mind maps on paper, I observed many of them becoming frustrated because they did not feel confident in their drawing abilities and they found that drawing the icons was time consuming (Abi-El-Mona & Adb-El-Khalick, 2008, p. 298-312). I believe that if my students have the opportunity to use Inspiration, which allows them to choose icons from an extensive bank of images, they would enjoy the mind mapping process more thoroughly (Inspiration, 2009). Integration of electronic mind mapping into subject learning While the benefits of electronic mind mapping are apparent, this teaching tool cannot be separated from subject-based learning. Tierney, Bond and Bresler caution 4 teachers against presenting new literacies, such as electronic mind mapping, as separate technical skills. They state, Oftentimes, these new literacies are framed as discrete skills such as programming, internet access, or presentation skills rather than as learning tools with complex palates of possibilities for students to access in a myriad of ways. It is as if learning with technology is being perceived as ‘learning the technology’ rather than using a range of multi-modal literacy tools (supported by these technologies) in the pursuit of learning (p. 2) I will therefore teach electronic mind mapping by contextualizing and integrating it into the regular classroom program. For example, in Language Arts, my students could use electronic mind mapping as a tool for story mapping, for brainstorming ideas, or for summarizing a novel. While mind mapping is not a new learning tool, by using electronic programs such as Inspiration and MindMeister, mind mapping becomes increasingly multi-modal and relevant to learners in the 21st century. Therefore, I believe that using electronic mind mapping in my Grade 4 class is imperative to promoting academic success for my students this upcoming year and throughout their academic careers. I believe that it will encourage my students to use a rich repertoire of modes, such as text, images, video and sound recordings, in order to summarize information, organize their thoughts, make sense of challenging concepts and integrate their understanding of ideas (Abi-El-Mona & Adb-El-Khalick, 2008, p. 298-312). Thank you, Principal Keene, for being open to the possibility of electronic mind mapping. I look forward to discussing this exciting endeavor with you. Sincerely, Kathleen Tilly 5 (Multimodal) Bibliography Abi-El-Mona, I. & Adb-El-Khalick, F. (2008, November). The influence of mind mapping on eight graders’ science achievement. School Science and Mathematics, 108 (7), 298-312. Adam, A. & Mowers, H. (2007, September). Get inside their heads with mind mapping. School Library Journal, 53(9), 24. Brinkmann, A. (2003, April). Graphical knowledge display – mind mapping and concept mapping as efficient tools in mathematics education. Mathematics Education Review, 16. Budd, J. W. (2004, Winter). Mind maps as classroom exercises. The Journal of Economic Education, 35(1), 35-46. Buzan, T. (n.d.). Buzan World: Mind Maps. Retrieved August 1, 2009. Web site: http://www.buzanworld.com Buzan, T. (n.d.). Maximize the power of your brain: Tony Buzan Mind Mapping. Retrieved August 2, 2009. Website: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MlabrWv25qQ Inspiration Software Inc. (2009). Retrieved July 30, 2009. Website: www.inspiration.com Meisterlabs. (2009). Retrieved July 30, 2009. Website: http://www.mindmeister.com Ministry of Education (2006), Language: Grades 1-8, Ontario: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Rowsell, J. Kosnik C. & Beck, C. (2008). Fostering multiliteracies pedagogy through preservice teacher education. Teaching Education, 19(2), 109-122. Tierney, R. J., Bond, E. & Bresler, J. (2006). Examining literate lives as students engage with multiple literacies. Theory Into Practice, 45(4), 359-367. 6