Arnold/Leavis to Hoggart

advertisement

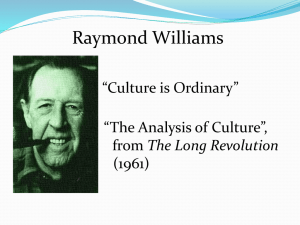

Seminar 4: The British Cultural Studies tradition from Arnold to Leavis, Hoggart & Williams. Seminar Reading: Scannell, P. (2007) Media and Communication chapter 4. The Industrial Revolution from the late 18th century onwards, and especially the major development of heavy industry in the mid-19th century along with the growth of large-scale capitalism exacerbated the potential for social unrest and conflict between the social classes. This reality along with the rise of revolutionary theories of Marx and of the anarchist, Bakunin provoked enormous fears across Europe of the overthrow of the ruling class – monarchs, aristocrats, capitalists, and so forth such as had happened in France in the 1790s. The authorities were active in suppressing radical political movements. However, there were other facets of the deepening class divide between the wealthy and the poor, one class and another that troubled the Victorian mind over and above any likelihood of revolution. This was the inhuman moral and cultural damage that a harsh poverty stricken life absent of faith, culture, and leisure, would promote. This world of humans reduced to little more than working beasts in the factories, and also what culture n the form of literature and poetry might bring to the human soul, was no better expressed than by the poet, Matthew Arnold in his wonderful 1870 essay: ‘Culture and Anarchy’. Famously he suggested that ‘sweetness and light’ would result from the transmission of good culture to the workers. This liberal vision of individuals gaining enlightenment and an intellectual freedom, opened up the connection between high culture and the populace in class society where culture was viewed as largely a matter for the middle and upper classes. In the 20th century, the Cambridge academic, F.R. Leavis and his wife Queenie developed an approach to the study of English literature exploring the relation between culture and class and, as early as 1930 began - albeit rather disdainfully – to look at the moral and cultural seriousness of popular literature. Leavis’s ideas that had focussed like Arnold’s upon the intellectual liberation of the class-bound individual, were from the late 1940s onwards, further opened out into a critique of class divisions and culture by the then socialist critics, Richard Hoggart (The Uses of Literacy 1957) and Raymond Williams (The Long Revolution, 1960) (who later became a marxist). After about 1955 there were major changes in society with the rise of a popular culture delivered by TV, new pop music etc., and this posed further problems for how to define the role of high culture – of literature and poetry in an increasingly mass culture and mass society of easy-going undemanding mass tastes. Themes of Seminar: ‘class’ and ‘mass’; popular v high culture; popular media.