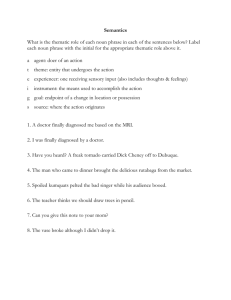

Basic Grammatical Concepts

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

Chapter 3:

Basic Grammatical Concepts

We have seen that an important goal of linguistic analysis is to identify and list the morphemes of a language and to determine which are roots and which are affixes. Roots are then classified as bound or free, affixes as prefixes or suffixes, and the suffixes as derivational or inflectional. All these tasks belong to the process of compiling a dictionary. We may now ask: does a dictionary of English fully account for its structure and use? Think of your experience studying a foreign language or traveling abroad.

Does a knowledge of the vocabulary of a language or possession of a bilingual dictionary make it possible to use the language the way native speakers do? Of course it doesn't.

We have already discussed some reasons why it doesn't when we examined a jumbled list of the words from an Emily Dickinson poem in Chapter 1 and showed how their meanings changed dramatically when rearranged into the grammatical sequences of the poem's sentences. Let us now look more closely at the same phenomenon, using another example. Read aloud and compare the two sequences of English words in 3.1 and 3.2.

Notice that both sequences contain the same words.

3.1 mornings the in beautiful most are mountains the

3.2 the mountains are most beautiful in the mornings

If you listened closely enough to your own reading, or if you now ask someone else to read the sequences aloud, you will notice that 3.1 reads like a list: the words are pronounced on a continuing monotone and perhaps with slight pauses between them.

However, in reading 3.2, the pitch of the voice rises and falls on the last word, and there are no pauses between the words. You might at this point want to say, “Of course!

That's because 3.2 is a sentence but 3.1 is not.” But let me risk belaboring the obvious, hoping to give some initial insight into just what a sentence is. When people who know

English hear 3.2, they do not just think of the dictionary meanings of mountains and beautiful ; they also associate the beauty with the mountains. No such association is conveyed in 3.1. Furthermore, this association in 3.2 is limited to a specific period of time, mornings. In 3.1, the word mornings bears no such relation to any other word or group of words in the sequence. The obvious observation is that the English language conveys meaning not only by using words, which are composed of meaningful morphemes, but also by arranging the words in a meaningful order.

We can isolate and observe these principles of word order more clearly by examining the following sequence, composed partly of English morphemes and partly of italicized nonsense syllables.

3.3 it was pab ious and the bept y crines marn ed and surdl ed in the dop

31

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

The italicized syllables, because they are not English morphemes and would not be entered in an English dictionary, are by definition meaningless segments. But if we read this sequence as if it were an English sentence, thereby evoking the word-order principles of English, then these meaningless segments begin to take on meaning imposed on them by the grammatical context. Students who are just learning English, given this sequence to read, might in fact assume that the italicized segments are meaningful, but that they must look up the words’ meanings in a dictionary. But even before going to a dictionary, one already has an idea that marn and surdle are verbs. Anyone would know this because both words carry a verb suffix, the past tense inflectional suffix, and because their positions in the sequence after the nouns and before the prepositional phrase is a position where verbs tend to occur in English. Furthermore, the words beginning pab and bept are probably adjectives, because of their positions in the sequence relative to other words and because they carry adjectival derivational suffixes. One can infer that dop is a noun because of its position at the end of the sequence after the . Moreover, even someone just learning English would probably also infer that dop specifies a place because it is in a prepositional phrase introduced by in .

The facts in the previous paragraph lead to this generalization: when English words are strung together according to certain ordering principles, meaning is conveyed by the ordering that is not contained in the meanings of the individual words in isolation. As we have already noted in chapter one, the linguist's description and explanation of these principles is termed syntax .

Any attempt to describe English syntax must show why 3.1 and countless sequences of English words like it are not English sentences, and why 3.2 and countless other sequences are English sentences. We could suggest that a description of English syntax might resemble the description of English morphology. We saw in Chapter 2 that morphemes may combine together to form words. All such combinations can be fully described by listing them in a dictionary. Thus when users of English encounter a sequence of sounds such as dop in 3.3, they evaluate it against a mental list of English morphemes and words, their internal dictionaries, and reject it as meaningless because it is not in those dictionaries. Might it be possible similarly to make a list of all those sequences of English words that are sentences and in this way explain that 3.1 is rejected because it is not on the list?

No one has ever seriously proposed such an approach to syntax, and it is easy to see why. Read the sentence in 3.4 and ask yourself: Is it an English sentence? Is it likely to be on any such list of English sentences?

3.4

Even though my friend seems normal, he insists on mixing milk, eggs, and yogurt with his cereal and eating it out of a sterling silver dish.

The answer to the first question is most assuredly Yes, and to the second question No.

Now, it is true that new entries can be added to the dictionary of words, for example, astronaut was added during the second half of the 20th Century.

Might it not also be true that sentences like 3.4, when they occur and are found to be syntactically acceptable, can be added to the "dictionary" of sentences? There is a difference. Most users of a language, while they are capable of inventing new words -- such as dop in 3.3 -- never

32

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS do. Or if they do, in jest, the words will not be understood by most other users of the language. However, every user of English creates sentences like 3.4 as a normal function of everyday language use. Whereas only several hundred items in a given year are added to the list of morphemes and words in English, the list of English sentences probably doubles every day. In fact, there is no effective limit on the number of sentences in

English, and therefore, any attempt to describe the syntactic versus non-syntactic sequences of words by making a list cannot succeed.

PARTS OF SPEECH: FORM, FUNCTION, AND MEANING

How, then, can the task of syntactic description be approached? At the beginning of

Chapter 1, I characterized linguistics as "the scientific study of language." The process of scientific description begins when generalizations are made that go beyond a simple listing of data. But such generalizations must refer to categories (classes) rather than to specific instances. What this entails for the study of syntax is that words must be grouped into classes according to their roles in forming sentences. Once such groupings are achieved, the principles of sentence structure can be expressed by reference to these classes.

The categories into which we group words in order to describe where they go and what they do in sentences have traditionally been called “parts of speech.” (A better term would be “parts of sentences,” because that is exactly what they are, but we will use the more widely recognized term, “parts of speech.”) Some linguists like to call them “form classes”; others have called them “substitution classes.” These differences in terminology reflect differences of emphasis when defining them, as we shall see.

Parts of speech are defined along three conceptual dimensions: form , function , and meaning . All three dimensions are important, but form and function are more important than meaning. This means that if the meaning of a word might indicate that it would be classified one way, but the form and function indicate something else, then form and function should decide. In the summary definitions of the various parts of speech presented in this book, form will be listed first, function second, and meaning third.

Traditional grammar often states that there are eight parts of speech in English, but there are many more than that. A careful application of the three criteria of definition will yield several dozen major categories of parts of speech and over a hundred subcategories.

Form

All parts of speech are defined formally by listing (i.e., by pure form). For example, we can say that a word is a noun if it is on the list of words that English speakers know to be nouns. This simply means that someone who knows English knows that words spelled and pronounced as cat, dog, house, shoe, etc. (i.e., the actual letter or sound sequences -- forms -- that signal their presence) all belong to the same formal category; they are stored together in the minds of speakers of English. It is this formal sameness that the term

“noun” labels.

Some parts of speech are also defined formally by noting which derivational suffixes may derive them from other words or which inflectional suffixes may attach to them.

33

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

Therefore, we can say that king, art, ball, car, door, ear, fruit, etc. are nouns because they are on the list of nouns (even though none of them contains a derivational suffix or inflectional suffix peculiar to a noun). We can say that kingdom, kindness, and truth are nouns both because they are on the list of nouns and because they end in noun-producing derivational suffixes. We can say that kings, balls, cars, king’s and John's are nouns because they are on the list of nouns and because they end in an inflectional suffix peculiar to nouns (either the plural inflectional suffix or the possessive inflectional suffix). The words kingdoms, kindnesses, and truths are nouns for all three formal reasons: they are on the list of nouns, their stems end in noun-producing derivational suffixes, and their final morpheme is an inflectional suffix peculiar to nouns (the plural inflectional suffix).

Let us take a moment to review briefly the distinction between derivational suffixes and inflectional suffixes in English. This distinction will play a role in the formal definitions of several parts of speech in addition to nouns. Suffixes, by definition are meaningful word parts that cannot occur as words on their own. A suffix may be attached directly to a root (as when we put the past tense suffix on pave to produce paved ), or a suffix may be attached to another suffix that has already been attached to the root of a word (as when we put the past tense suffix on the word symbolize , which already consists of the root symbol and the suffix -ize , to produce symbolized ).

Here are three ways to tell derivational and inflectional suffixes apart: (a)

Derivational suffixes tend to change the part of speech, but inflectional suffixes never do so. (When we add the derivational suffix -ment to the verb pave , we produce the noun pavement , but when we add the past tense inflectional suffix to the verb pave , producing paved , it remains a verb.) However, derivational suffixes do not always change part of speech. (Both king and kingdom are nouns.) (b) When a derivational suffix appears together with an inflectional suffix in a given word, the derivational suffix must precede the inflectional suffix. (“Words” like

*pavedment , or *kingsdom are thus impossible.)

(c) Words with derivational suffixes (e.g., pavement and kingdom ) are entered separately in the dictionary, but the inflected forms of words, e.g., the plural of a noun or the past tense of a verb, do not have separate dictionary entries.

English has dozens of derivational suffixes but only eight inflectional suffixes: two that attach to nouns: the plural inflectional suffix ( books ) and the possessive inflectional suffix ( John’s ); four that attach to verbs: the present tense inflectional suffix ( eats ), the past tense inflectional suffix ( paved ), the present participle inflectional suffix ( eating ), and the past participle inflectional suffix ( broken ); and two that attach to many adjectives and a few adverbs: the comparative inflectional suffix ( faster ) and the superlative inflectional suffix ( fastest ).

Function

Function is position. We define the linguistic function of any category when we make statements about where to put it in relation to other categories. If we are defining the function of parts of speech, we do not, in fact, state where they occur in relation to other parts of speech in clauses or sentences; rather, we state where they occur in relation to other parts of speech in phrases, which in turn group with other phrases to form clauses and sentences. Nouns have two key functions in noun phrases: They can function as

HEAD of a noun phrase, and they can function as a MODIFIER in a noun phrase. Here

34

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS are some examples: In the sentence, The students wrote excellent papers, there are two noun phrases, the students and excellent papers. The nouns, students and papers are

HEADS of their respective noun phrases. The grammatical function of HEAD (of any type of phrase) is defined as that part of speech which can play the role of the whole phrase all by itself. (Notice that we still have a perfectly grammatical English sentence if we say, Students wrote papers, using only the HEAD nouns, but we no longer have a sentence if we tried to say, the wrote excellent, leaving out the HEAD nouns.) Another part of the definition of HEAD of a noun phrase is that it occupies the position after

DETERMINERS like the and MODIFIERS like excellent.

The second typical function of nouns is that of MODIFIER in a noun phrase. Here are some examples, with the noun

MODIFIERS in boldface type: college students, fire engines, student assistants , and

coffee stains.

Meaning

For traditional grammarians (and traditional English teachers) meaning was the primary criterion for defining parts of speech. Most of us remember studying, or at least hearing or reading in our early years of school, that nouns are “words that name persons, places, or things.” For the most part the definition holds up, but there are many, many nouns that do not fit easily into one of those three categories, for example, truth, thought, quality, tangent, action, dream, ownership, arrival . The word arrival is certainly not a person, place, or thing; it is an action. (In fact, the term “action” is typically used as part of the meaning-based definition of a verb!) Notional definitions (as definitions based on meaning are sometimes called) are useful and relevant, but they are difficult to test and verify. This is why form and function take precedence in classifying the part of speech of a word even when they might contradict meaning. In later chapters, we will look at many more parts of speech besides the noun, and in each case, we will apply the three criteria of form, function, and meaning to defining them.

PRACTICE 6 (DEFINING “NOUN”)

Consult a college desk dictionary, and look up the definition of the word noun as a grammatical term. (i) Does the definition include discussion of all three dimensions of the concept of a part of speech: form, function, and meaning? (ii) Which specific parts of the definition relate to each of these three aspects? (iii) How do the details of the definition relate to the definition of a noun given in this section of this chapter; i.e., is the dictionary more or less complete or more or less accurate than the definition presented in this chapter? Go to a library and look up the definition of a noun in an unabridged dictionary such as

Webster’s Third New

International Dictionary or The Oxford English Dictionary. Compare each definition to the one given in this section by answering these same three questions (i to iii).

PRACTICE 7 (“NOUN”: A CLOSER LOOK)

While in the library, find the book, Understanding Grammar by Paul Roberts. This is one of the more scholarly traditional grammars, and has been in print for nearly forty years. When you find it, first check out the brief definition of a noun in the Glossary. Notice how effectively the definition refers to form, function, and meaning (and in that order) in a very short space. Then

35

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS read the first paragraph of Chapter 2, which treats nouns in depth. This paragraph contains an excellent argument for the primacy of form and function over meaning when defining nouns.

PRACTICE 8 (“NOUN”: AN INTERNET SEARCH)

If you have access to the World Wide Web on the Internet, do a search using the phrase

“English Grammar,” Open a few of the more promising hits and find out how each one defines a noun. Then compare their definitions to the one given in this section by answering the same three questions as in Practice 3 above: (i) Does the definition include discussion of all three dimensions of the concept of a part of speech: form, function, and meaning? (ii) Which specific parts of the definition relate to each of these three aspects? (iii) How do the details of the definition relate to the definition of a noun given in this section of this chapter; i.e., is the dictionary more or less complete or more or less accurate than the definition presented in this chapter?

FEEDBACK TO PRACTICE 6 (DEFINING “NOUN”)

In The American Heritage College Dictionary, Third Edition , a noun is defined as follows:

“A word that is used to name a person, place, thing, quality, or action and can function as the subject or object of a verb, the object of a preposition, or an appositive.” (i) The definition discusses meaning and function, but it does not mention form. (ii) Up to the word action , the definition is discussing meaning; the remainder discusses function. (iii) It states that nouns can name a “quality.” This term was not included in the discussion of the meaning of a noun in this chapter section. It defines the functions (positions) of a noun not in terms of where they go in the noun phrase (HEAD or MODIFIER), as we did in this chapter, but in terms of the positions of the whole noun phrase in a clause. (Terms like “subject,” “object,” and “object of a preposition” are positions that whole noun phrases occupy in clauses). There is no mention at all of nouns being defined by their spelling (pure form) or by the fact that certain derivational or inflectional suffixes are attached to them.

FEEDBACK TO PRACTICE 7 (“NOUN”: A CLOSER LOOK)

In the Glossary of Understanding Grammar (Harper & Row, Publishers, 1954, p. 508), Paul

Roberts defines a noun as follows: “A word, identifiable by certain characteristics of form and position, that names a living being or a thing.” Here is a slightly adapted quotation of the first paragraph of Chapter 2 of the Roberts’ book (p. 25): “Nouns have most often been defined

[according to their meaning]: ‘A noun is the name of a person, place, or thing.” When it is felt that ‘thing’ is too vague a word for the definition, other terms are added: ‘A noun is the name of a person ( Erwin Gilliam, Shiela, cowboy ), place ( Third Street, country, Mount Shasta ), concrete object ( pencil, fence, cup ), mass or material ( gravel, water, blood ), quality ( redness, strength, humility ), action ( resistance, arrival, stealing ), abstract concept ( idea, triviality, philosophy)

.’

This definition has certain weaknesses. First of all it is circular; noun and name being two forms of the same word, it is like saying ‘A name is the name of a person, place, or thing.’ What we need to find out is how we know that certain words name things and are therefore nouns.

Further, no matter how many terms we add to the definition, we shall always find nouns that do not fit very well in any of the subdivisions. Where shall we put such (undoubted) nouns as time, instruction, responsibility ? Is triviality really an abstract concept, or is it perhaps an object?

[Classification of nouns based on meaning] is really a classification of the matters of the universe, and this is not a major responsibility of grammar.”

36

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

FEEDBACK TO PRACTICE 8 (“NOUN”: AN INTERNET SEARCH)

When I performed such a web search, my computer presented me with hundreds of Web sites that dealt in some way with English grammar. Many of them seemed aimed at meeting the learning needs of students of English as a second language; some treated grammar as a part of

English usage and focused on helping writers avoid the kinds of grammatical structures that are not appropriate in formal written essays. Some were grammars written as part of artificial intelligence and computer-assisted translation research projects. I found it relatively easy to find definitions for nouns in several of the sites, and to determine that most of them focused on meaning, often not even mentioning form and function, when defining nouns.

CONSTITUENT STRUCTURE

In Chapter 1, when we looked closely at the words of an Emily Dickinson poem, first presented in a jumbled order and then in the order in which she wrote them, we had a dramatic exhibition of what makes a sentence. A second example of this phenomenon was given in 3.1 and 3.2 at the beginning of this chapter. In each case, the same English words that, in one order, were a random list, in another order, expressed a rich array of relational meanings. Here is yet another example, but with a twist:

3.5a

*enthusiasm with candidate the selected delegates the

3.5b

The delegates selected the candidate with enthusiasm.

The very same words that are nonsense in 3.5a are a clear and meaningful sentence in

3.5b. One way to use parts of speech to explain this would be to describe English sentence structure in terms of linear patterns of part-of-speech labels. We would then say that (5b) is a sentence because it follows the pattern in 3.6:

3.6 definite article + noun + verb + definite article + noun + preposition + noun

The delegates selected the candidate with enthusiasm .

On the other hand, 3.5a is not a grammatical English sentence because the reverse pattern of parts of speech is not part of English grammar. The pattern in 3.6 has the added

(scientific) advantage of describing countless other sentences in English, sentences like

The students liked the study of linguistics, The woman bought the car with overdrive, and

The President read the letter from Congress.

There was a time when grammar books such as this sought to explain sentence structure in just this way, by listing as many English sentence patterns as could be discussed and described between the pages of a normal sized book. But if you read 3.5b again ( The delegates selected the candidate with enthusiasm ), you will notice something about it that shows that sentence structure is more than simple word order, and therefore

37

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS linear sentence patterns cannot fully explain it. Even though 3.5b contains no ambiguous words, and each word belongs only to the part of speech listed in the pattern immediately above it in 6, it actually represents two English sentences. In the overview in Chapter 1

(p. 6), I defined the sentence as "an arrangement of words where the words act on one another, specifying and even changing one another's meanings, and thus expressing relationships and connections among the entities to which the words refer." In 3.5b the phrase with enthusiasm can be interpreted as having two entirely separate kinds of relationship to other words in the sequence, thus proving that the same sequence of words, representing the same linear pattern of parts of speech, is indeed two sentences. The two interpretations are represented in 3.7a and 3.7b:

3.7a

[ The delegates ] [ selected ] [ the candidate with enthusiasm ] .

(Under this interpretation, the delegates selected the enthusiastic candidate; enthusiasm is related to the candidate -- whom we picture smiling and waving. Because the prepositional phrase with enthusiasm is part of the same noun phrase with the words the candidate, it cannot be moved to the front of the sentence, without changing its relational meaning.)

3.7b

[ The delegates ] [ selected ] [ the candidate ] [ with enthusiasm ] .

(Here, the delegates selected the candidate enthusiastically; enthusiasm is related more to the delegates -- we picture them cheering as they vote -- and to how they performed the act of selecting the candidate. Because the prepositional phrase with enthusiasm is related more or less equally to all of the other elements of sentence structure, this relational meaning would be preserved if it were moved to the front of the sentence: With enthusiasm, the delegates selected the candidate .)

In the interpretation represented in 3.7a, the prepositional phrase with enthusiasm is part of the DIRECT OBJECT noun phrase and thus POST MODIFIES the HEAD noun candidate.

Its syntactic relationship is solely to the other two words that are grouped together with it in the DIRECT OBJECT noun phrase (it identifies which candidate was selected: the one with enthusiasm ). However, in the interpretation represented in 3.7b, the prepositional phrase with enthusiasm is not part of the DIRECT OBJECT noun phrase; it occupies an independent position in the clause (which we may label FINAL

CLAUSE COMPLEMENT and is thus related syntactically to all of the remaining words in the sentence not just to the DIRECT OBJECT (it describes how the delegates selected the candidate; under this interpretation, we are told nothing about whether the candidate had enthusiasm or not). Notice that the relational meaning of with enthusiasm in 3.7a can be paraphrased by modifying the noun candidate with the adjective enthusiastic, and the relational meaning of with enthusiasm in 3.7b can be paraphrased by substituting the adverb enthusiastically in the same CLAUSE COMPLEMENT position as with enthusiasm.

Structurally ambiguous sentences like The delegates selected the candidate with enthusiasm provide especially dramatic proof of an important fact about every sentence:

The grammar of a sentence cannot be fully described simply by listing a linear pattern of part-of-speech labels. This is because words in sentences are structured into groups

(phrases and clauses) and those groups can be inside of other groups. This hierarchy of group structure in sentences is called constituent structure . Every sentence has a

38

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS constituent structure, and one of the jobs of the grammarian is to describe the constituent structure of sentences and to explain where such structures come from.

We have already, in fact, taken a fairly close look at the constituent structure of one

English sentence when we analyzed a part of the Emily Dickinson poem in Chapter 1 (cf. pp. 5-9). There, the constituent structure of the sentence, A word is dead when it is said, was represented in an outline format. Let us compare the two interpretations described in

3.7a and 3.7b using the same outline format:

3.7a'

Declarative Clause

SUBJECT Noun Phrase

DETERMINER Definite Article

HEAD Noun

PREDICATER Verb Phrase

MAIN PREDICATER Verb

DIRECT OBJECT Noun Phrase

DETERMINER Definite Article

HEAD Noun

POST MODIFIER Prepositional Phrase

RELATER Preposition

OBJECT OF A PREPOSITION Noun Phrase

HEAD noun

3.7b'

Declarative Clause

SUBJECT Noun Phrase

DETERMINER Definite Article

HEAD Noun

PREDICATER Verb Phrase

MAIN PREDICATER Verb

DIRECT OBJECT Noun Phrase

DETERMINER Definite Article

HEAD Noun

CLAUSE COMPLEMENT Prepositional Phrase

RELATER Preposition

OBJECT OF A PREPOSITION Noun Phrase

HEAD noun

The delegates selected the candidate with enthusiasm

The delegates selected the candidate with enthusiasm

Constituent structure can also be represented by using diagrams that are similar to the kind of organization charts that are often used to show the hierarchy of officers and divisions in a corporation. The difference is that, in addition to naming the (formal) entities that define the various levels in the hierarchy, their (functional) relationships are also labeled. In 37a'' and 3.7b'' you will find such diagrams that correspond to the representations just above. Because of space limitations, abbreviations will be used for the functional and formal labels used in the outline format above. Before reading on, examine the two hierarchical tree diagrams carefully, and compare them to each other and to their equivalents in the outline format above.

39

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

3.7a’’

declcl>

S: P: DO:

np> vp> np>

D: H: MP: D: H: PM: dart... n... v... dart... n... pp>

R: OP:

p... np>

H:

n...

The delegates selected the candidate with enthusiasm

3.7b’’

declcl>

S: P: DO: FCC:

np> vp> np> pp>

D: H: MP: D: H: R: OP: dart... n... v... dart... n... p... np>

H:

n...

The delegates selected the candidate with enthusiasm

The diagrams in 3.7a'' and 3.7b'' correspond exactly to 3.7a' and 3.7b' in what they say about the constituent structures of 3.7a and 3.7b respectively. Even though they seem more technical and unfamiliar at first sight, their tree-diagram format has many advantages over the outline format. For one thing, it allows the words in a sentence to be represented on the page in their usual left-to-right order. For another thing, they graphically (pun intended) dramatize the difference between the functional labels and the formal labels of constituents. The functional labels (with the colons after them) actually label the branches that they directly hang on to. In fact they are the branches. (You might even imagine the diagram with the word "SUBJECT" written on the branch or in place of the branch, thus labeling the space to the left of the PREDICATER and literally

40

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS connecting the label np> to the label declcl> as the way of indicating that the np> ( the delegates ) is indeed the SUBJECT OF the declarative clause. It is thus very important to remember that functional labels actually label branches above them and the spaces that the branches occupy; whereas, formal labels classify the word or words that are grouped below them.

Just in case you are interested, traditional grammatical diagrams of the two interpretations discussed in 3.7a and 3.7b are given below, and labeled 3.7a’’’ and

3.7b’’’. Notice three things about the traditional diagrams below that make them inferior to tree diagrams above: (1) They too (like the outline format) distort the word order. (2)

The various spaces in them give information only about function (the SUBJECT is to the left of the tall vertical line; the PREDICATER between the vertical lines, and the

DIRECT OBJECT after the short vertical line; DETERMINERS and MODIFIERS are on slanted lines below the words they DETERMINE or MODIFY -- though the distinction between these functions is not clearly represented). (3) They give no information of any kind about form: clause types, phrase types, and parts of speech are not labeled.

7a’’’ d e l e g a t e s s e l e c t e d c a n d i d a t e

T t w

h h i

e e t

h

e n t h u s i a s m

7b’’’ d e l e g a t e s s e l e c t e d c a n d i d a t e

T w t

h i h

e t e

h

e n t h u s i a s m

ENGLISH GRAMMAR: PATTERNS AND CHOICES

Thus far in this chapter, we have discussed the need to identify and define parts of speech as the necessary first step in describing English sentence structure. We have also examined the existence of, and a few ways of representing, constituent structure -- the organization of words into phrase and clause groups in sentences. Every sentence consists of a sequence of words, each one belonging to a particular part of speech and each part of speech participating in some kind of phrase, which may in turn be part of another phrase or directly part of a clause.

The next question we need to address is this: Where do constituent structures come from? Or, to put it another way, what do you and I know that makes it possible for us to

41

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS produce and understand the constituent structures of the hundreds of sentences we encounter each day? Remember, the constituent structure of a sentence is the set of meaningful relationships that makes it a sentence. Might it be that we have experienced each sentence previously and memorized its meaningful relationships, the way we memorize the meanings of new words we learn? That is highly unlikely. We humans are indeed capable of memorizing tens of thousands of vocabulary words, but it is stretching the imagination to think that we understand the meaningful relationships in sentences because we have encountered each sentence before. In fact, linguists like to claim that most of the sentences we encounter in speech and writing are uniquely new in how they arrange their words and thus also the ideas to which the words refer.

To put the issue yet another way, the grammar of a language is not a collection of prefabricated constituent structures. Rather it is a set of principles for creating the constituent structures that we need in order to express meaningful relationships we want to communicate to others. The grammar of a language is thus like a set of directions, or principles, for assembling words into phrases and phrases into clauses.

What might such a set of principles look like? To answer this question, I have constructed a tiny fragment of the grammar of the English declarative clause. Even though it contains directions for assembling only declarative-clause constituent structures

(saying nothing about interrogative clauses, or imperative clauses, or compound or complex sentences of any kind), and even though it doesn’t even fully explain the grammar of the declarative clause, it does account for the meaningful relationships expressed in both interpretations of the sentence, The delegates selected the candidate with enthusiasm. Furthermore, even though it makes reference to only a few dozen words, it also accounts for the constituent structures of literally thousands of other

English sentences (that use only those few dozen words). You will find this fragmentary grammar in 3.8a to 3.8z beginning on this page and continuing onto the next two pages.

Take a few minutes to look it over, and then proceed to the explanation on the pages following it.

As you examine it, remember that the constituent structures (in outline format and tree format) that we have discussed in this chapter and in chapter 1 contained two types of information about words and phrases: (1) functional information (labels for their positions) and (2) formal information (labels for their clause, phrase, or part-of-speech type). See if you can determine which parts of the sample grammar account for function and which parts account for form.

3.8

A Fragment of the Grammar of the English Declarative Clause

3.8a declcl> (ICC:) + S: + P: + ( (IO:) + DO:) + (FCC:)

3.8b

S: np>

3.8c

P: vp>

3.8d

42

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

DO: np>

3.8e

IO: np>

3.8f

ICC: and FCC: pp>

3.8g

ICC: and FCC: advp>

3.8h np> (D:) + (M:) + H: + (PM:)

3.8i

H: n...

[proper, human] John

[common, abstract, noncount] enthusiasm

[common, concrete, human, count, chooser, singular] delegate

[common, concrete, human, count, chooser, plural] delegates

[common, concrete, human, count, choice, singular] candidate

[common, concrete, human, count, choice, plural] candidates

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, place, singular] convention

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, place, plural] conventions

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, money, illegal, singular] bribe

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, money, illegal, plural] bribes

3.8j

M: adj...

[valuable, positive] good

[valuable, comparative] better

[valuable, superlative] best

[emotion] enthusiastic

3.8k

M: n...

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, place, singular] convention

3.8l

D: dart...

[identifiable] the

3.8m

D: iart...

[specific, singular] a/an

[specific, plural] some

[generic, singular] a/an

[generic, plural] some

3.8n

PM: pp>

43

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

3.8o pp> R: + OP:

3.8p

R: p...

[accompaniment] with

[location] at

3.8q

OP: np>

3.8r advp> H:

3.8s

H: adv...

[manner] enthusiastically

[time] then

[place] there

3.8t vp> MP:

3.8u vp> MODHP: + (SN:) + MP:

3.8v vp> PROHP: + SN: + MP:

3.8w

MP: v...

[noDO:, nonfinite] arrive

[noDO:, finite, past] arrived

[noDO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] arrive

[noDO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] arrives

[yesDO:, nonfinite] select

[yesDO:, finite, past] selected

[yesDO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] select

[yesDO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] selects

[yes/noDO:, nonfinite] help

[yes/noDO:, finite, past] helped

[yes/noDO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] help

[yes/noDO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] helps

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, nonfinite] give

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, finite, past] gave

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] give

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] gives

3.8x

MODHP: modaux...

44

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

[possibility, past] might

[possibility, present] may

[certainty, past] would

[certainty, present] will

3.8y

PROHP: proaux...

[nonfinite] do

[finite, past] did

[finite, present, non3rdsng] do

[finite, present, 3rd sng] does

3.8z

SN: neg...

[negative] not

In examining the various lines in 3.8a to 3.8z, you should first have noticed that some are printed in bold-face type and others are not. The lines in boldface type represent grammatical patterns in the declarative clause; those in regular type represent grammatical choices in the declarative clause. Notice that each pattern line begins with the abbreviation of a formal clause or phrase label to which an arrowhead symbol is attached. To the right of that label appear functional position labels with colons attached.

These functional position labels are separated by plus signs, and some are in parentheses.

These notations seek to represent the fact that you and I (and anyone who knows the

English language) know the following centrally important things about each English clause or phrase type: We know what meaningful relational positions may occur within that clause or phrase type and we know the exact order of the positions. Here is a reprint of 3.8a:

3.8a declcl> (ICC:) + S: + P: + ( (IO:) + DO:) + (FCC:)

The most important thing that it tells us about the English declarative clause is that every declarative clause must have a SUBJECT position, S:, and a PREDICATER position, P:, and that they must appear in that order. The pattern also tells us that they must appear, because their symbols are not in parentheses. We know that they must appear in that order because the S: precedes the P: in the pattern. The pattern also tells us that a

DIRECT OBJECT, DO:, may follow the PREDICATER, but does not have to do so.

The parentheses around DO: in the pattern indicate that the choice of DIRECT OBJECT is optional. Notice that, inside the parentheses containing the DIRECT OBJECT is another set of parentheses containing the abbreviation IO:, for INDIRECT OBJECT.

This notation indicates that if A DO: occurs (and only if one occurs) it may or may not be preceded by an INDIRECT OBJECT. The sentence in 9a represents a realization of the S: + P: pattern, the sentence in 9b represents a realization of the S: + P: + DO: pattern, and the sentence in 9c represents a realization of the S: + P: + IO: + DO: pattern.

3.9a

The candidate | arrived.

45

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

3.9b

The delegates | will select | a candidate.

3.9c

The candidate | will give | the delegates | a bribe.

The pattern in 3.8a also indicates that an optional INITIAL CLAUSE COMPLEMENT

(ICC:) may precede the SUBJECT, or an optional FINAL CLAUSE COMPLEMENT

(FCC:) may follow a DIRECT OBJECT or INDIRECT OBJECT and DIRECT OBJECT

(if one or both occur) or may follow the PREDICATER (if there is no DIRECT OBJECT or INDIRECT OBJECT and DIRECT OBJECT). CLAUSE COMPLEMENTS are typically adverbs, such as enthusiastically or prepositional phrases such as with enthusiasm. The declarative clause pattern in 8a thus allows either enthusiastically or with enthusiasm to occur either at the beginning or at the end of any of the three sentences in 9.

There is another way to interpret the symbolic notation in 3.8a, and that is as directions for drawing constituent structure tree diagrams. From this point of view, the arrowhead after a clause or phrase abbreviation can be interpreted to mean this: "In a tree diagram, draw lines down from the formal phrase or clause label to the left of the arrow

3.8b

S: np>

3.8c

P: vp>

3.8d

DO: np>

3.8e

IO: np> to functional position labels as indicated in the pattern to the right of the arrow." The plus signs in the pattern are thus interpreted as separating the position labels that have their own lines drawn to them. Thus, the pattern in 3.8a would generate the following partial tree for the sentence in 3.9b:

3.9b’

declcl>

S: P: DO:

The delegates | will select | a candidate.

Now, what about the lines in 8 that are not printed in boldface type, the lines that represent grammatical choices? Here are the choice lines for the declarative clause, 3.8b to 3.8g:

46

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

3.8f

ICC and FCC: pp>

3.8g

ICC: and FCC: advp>

Notice that each choice line begins with the abbreviation of a functional position label. It is S: in 3.8b, P: in 3.8c, DO: in 3.8d, IO: in 3.8e, and ICC: and FCC: in 3.8f and 3.8g. To the right of the colon attached to each position label, you will find the abbreviations of formal categories of various kinds. The meaning of the notation in 3.8b (S: np>) may be read as follows: "The SUBJECT position in an English declarative clause may be filled by a noun phrase." Similarly, 3.8c (P: vp>) states that the PREDICATER position may be filled by a verb phrase, 3.8d (DO: np>) states that the DIRECT OBJECT position may be filled by a noun phrase, and 3.8e (IO: np>) states that the INDIRECT OBJECT position may also be filled by a noun phrase; 3.8f (ICC: and FCC: pp>) states that both the INITIAL CLAUSE COMPLEMENT position or the FINAL CLAUSE

COMPLEMENT positions may be filled by a prepositional phrase and 3.8g (ICC: and

FCC: advp>) states that both the INITIAL CLAUSE COMPLEMENT position and the

FINAL CLAUSE COMPLEMENT positions may be filled by an adverb phrase.

And just as the arrowhead and plus signs in patterns can be viewed as giving directions on how to generate a constituent structure tree diagram by drawing lines to and inserting the position labels within a clause or phrase, so too the colons in the choice lines in the grammar can be viewed as giving directions about which formal categories may be chosen to insert at designated positions in a pattern (i.e., which category labels should hang on the branches labeled by the position labels). Whereas the arrowhead means

"Draw a line," the colon means "Make a choice." Thus, 3.8b, 3.8c, and 3.8d account (in left to right order) for the following three additions to the diagram in 3.9b':

3.9b’’

declcl>

S: P: DO:

np> vp> np>

The delegates | will select | a candidate.

Let us pause now to remind ourselves what the diagram in 3.9’’ tells us about the sentence: (1) The delegates will select a candidate is a declarative clause (all the branches in the tree converge on declcl> at the top); (2) within that declarative clause,

The delegates is a noun phrase (its formal label is np>) and it occupies the position of

SUBJECT (its functional label is S:); similarly, (3) will select is a verb phrase (vp>) functioning as PREDICATER (P:); and (4) a candidate is a noun phrase (np>) functioning as DIRECT OBJECT (DO:). Notice how many lines of printed text it just took in this paragraph to state in words the information contained in the diagram in

3.9b’’. Even though such diagrams can seem intimidating when first encountered, they are much more explicit and concise than long verbal descriptions.

47

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

Remember that the grammar presented in 3.8 is greatly oversimplified so that you can learn something about how such grammars work. That is, we know that other types of formal categories besides noun phrases can in fact fill the SUBJECT position or DIRECT

OBJECT position in English declarative clauses, but I have chosen not to complicate the current discussion by including them in this particular sample grammar. (Here are just two examples of such additional possibilities: In the sentence Casting ballots will select a candidate , the SUBJECT is not a noun phrase; it is the gerund clause casting ballots , and in the sentence The delegates chose to cast ballots , the DIRECT OBJECT is not a noun phrase; it is the infinitive clause to cast ballots .)

Now, let us look a little more closely at the grammar of the English noun phrase as represented in the noun-phrase patterns summarized in 3.8h and the noun-phrase choices listed in 3.8i to 3.8n:

3.8h np> (D:) + (M:) + H: + (PM:)

3.8i

H: n...

[proper, human] John

[common, abstract, noncount] enthusiasm

[common, concrete, human, count, chooser, singular] delegate

[common, concrete, human, count, chooser, plural] delegates

[common, concrete, human, count, choice, singular] candidate

[common, concrete, human, count, choice, plural] candidates

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, place, singular] convention

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, place, plural] conventions

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, money, illegal, singular] bribe

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, money, illegal, plural] bribes

3.8j

M: adj...

[valuable, positive] good

[valuable, comparative] better

[valuable, superlative] best

[emotion] enthusiastic

3.8k

M: n...

[common, concrete, nonhuman, count, place, singular] convention

3.8l

D: dart...

[identifiable] the

3.8m

D: iart...

[specific, singular] a/an

[specific, plural] some

[generic, singular] a/an

[generic, plural] some

3.8n

PM: pp>

48

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

The pattern in 3.8h indicates that every noun phrase must have an H: position (i.e., a

HEAD). The HEAD may occur alone or with up to two positions preceding it and one position following it. A DETERMINER (D:) and/or a MODIFIER (M:) may precede, and a POST MODIFIER (PM:) may follow the HEAD.

The first choice in the noun phrase, line 3.8i, indicates that the HEAD position in a noun phrase can be occupied by a noun. For the moment, ignore the lines of terms in square brackets and note simply that all of the words in italic type at the ends of those lines in 3.8i are nouns. Choice lines 3.8j and 3.8k indicate that the MODIFIER position may be filled either by an adjective (e.g., good candidates, enthusiastic delegates ) or a noun (e.g., convention delegates ). Choice lines 8l and 8m indicate that the

DETERMINER position may be filled by either a definite article (e.g., the delegates ) or an indefinite article (e.g., a candidate, some delegates, any convention, no enthusiasm ).

And choice line 3.8n indicates that a prepositional phrase can occupy the POST

MODIFIER position. (e.g., delegates at the convention ). A noun phrase could have a

DETERMINER, MODIFIER, and HEAD (e.g., the enthusiastic delegates ), or even a

DETERMINER, MODIFIER, HEAD, and POST MODIFIER (e.g., the enthusiastic delegates at the convention).

Let us now look at the lines of square-bracketed terms in 3.8i, which represent a system network of semantic choices that seek to explain both how the meanings of

English nouns might be represented in a grammar and how their definitions might be displayed in a constituent structure tree diagram. For example, the choice of the word delegates for inclusion in sentence 3.9b ( The delegates will select a candidate ) is explained by 3.8i as, first, the choice of a noun (N...). Then the following semantic choices are made: the term [proper] appears, classifying John as a proper noun. The alternate choice is [common], which appears as the first defining term of the next noun listed, enthusiasm , and of all the other nouns included in this grammar. The next distinction is [abstract] versus [concrete] ( enthusiasm is abstract; all the other nouns are concrete]). The particular set of terms that define delegates is in the fourth line and can be displayed in a constituent structure tree diagram as illustrated in 3.9b’’’:

3.9’’’

declcl>

S: P: DO:

np> vp> np>

H:

n...

[common]

[concrete]

[human]

[count]

[chooser]

[plural]

The delegates | will select | a candidate .

49

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

Most of the terms used to define delegates are familiar to semanticists and grammarians.

A few of the terms I include in the lists of definitions in 3.8i, e.g., [chooser] versus

[choice], are ad hoc terms that I invented just for this sample grammar so that I could indicate the difference in meaning between delegate(s) , who choose candidates, and candidate(s) , who are chosen by delegates at a convention. A complete grammar of

English would have to use dozens, or perhaps hundreds, of terms in order to assign a unique set of defining features to each of the thousands of nouns in English.

Take another look at the sample grammar on pages 44 to 46, carefully examining the sets of square bracketed terms that assign meanings to all the words contained in the grammar. Some, like the terms in 3.8l for the definite article, are quite simple, requiring only one feature, [identifiable], to define the.

This is because the is the only word belonging to its part-of-speech category. The indefinite article in 3.8m is more complex since more words need to be defined and distinguished, and some words, like any and no , need to be assigned multiple meanings.

Even though a complete constituent structure diagram of a sentence would contain a set of semantic features defining each word in the sentence, grammarians do not typically take the time to include them in diagrams, and teachers do not typically require students to include them either. Thus, the diagram generated by the grammar in 3.8 for sentence

3.9b would look like this:

3.9b’’’’

declcl>

S: P: DO:

np> vp> np>

D: H: MODHP: MP: D: H: dart... n... modaux... v... iart... n...

The delegates will select a candidate.

Most grammar books that use constituent structure tree diagrams draw all the lines in such diagrams as solid lines. The diagram above and others throughout this book use solid lines to represent functional positions within clauses and phrases but use dotted lines to connect part-of-speech labels to the words they categorize. I do this for two reasons: (1) The solid lines are , in fact, functional positions; i.e. the functional label at the end of each such line actually is the line (and could just as well be written on the line). (2) The dotted lines do not represent functional positions within a part of speech

(because parts of speech do not have functional positions within them); rather , the dotted lines do two things: (a) they connect part-of-speech labels to the words that they categorize and (b) they simultaneously remind us that there is a set of defining semantic features that could be included in the diagram where each dotted line occurs.

This important distinction between two types of formal category labels in grammar is symbolized (and reinforced for pedagogical purposes) by the different notations I use, on

50

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS the one hand, for clause and phrase labels (which have > attached), and, on the other hand, for part-of-speech labels (which have ... attached). The symbol > in labels such as declcl> or np> means "Draw lines to functional position labels as indicated in the pattern to the right of > in this pattern line." However , the symbol ... in labels such as n... or v... means "Work through the lists of semantic features following the part of speech label until you reach a particular word that realizes and is categorized by this label."

Whereas formal category labels in the grammar presented in this book are thus subdivided into two types (clauses and phrases versus parts of speech), there is no such conceptual distinction between the position labels for clauses and phrases and the position labels for parts of speech: all function labels have a colon attached, and the colon in every case means "You may choose a category (clause, phrase, or part of speech) to occupy this position as indicated by the possibilities listed to the right of the colon in this choice line."

Let us now look a little more closely at the grammars of the prepositional phrase, adverb phrase, and verb phrase that are partially represented by the patterns and choices in 3.8o to 3.8z on pp. 44 to 46. The pattern in 3.8o describles the relatively simple grammar of the prepositional phrase:

8o pp> R: + OP:

Notice that there are no labels in parentheses and thus no optional choices. Every prepositional phrase has two positions: R: (RELATER) and OP: (OBJECT OF A

PREPOSITION). Lines 3.8p and 3.8q indicate that the RELATER position is occupied by a preposition (p...), and the OBJECT OF A PREPOSITION position is occupied by a noun phrase (np>):

3.8p

R: p...

[accompaniment] with

[location] at

3.8q

OP: np>

Only two of the dozens of prepositions in English are included in the sample grammar: with and at.

The grammar of the adverb phrase as presented in 3.8r and 3.8s is even simpler than that of the prepositional phrase:

3.8r advp> H:

3.8s

H: adv...

[manner] enthusiastically

[time] then

[place] there

51

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

According to the pattern in 3.8r and the choice in 8s, an adverb phrase has one position, the HEAD position, and that position is filled by a word belonging to the part of speech, adverb, only three of which are listed in the grammar: enthusiastically, then, and there.

In fact, there are perhaps thousands of other adverbs in English and many of them can have modifying intensifiers, as in the adverb phrase, quite enthusiastically , but I have chosen not to include such possibilities in the small fragment of the grammar of the declarative clause that we are using in this section as a vehicle to understand what a grammar is and how a grammar generates constituent structures.

Finally, let us look at the fragment of the grammar of the verb phrase presented in

3.8t to 3.8z on pp. 44 to 46 (reprinted following this paragraph for ease of reference).

Even though this too has been simplified for our present purposes, three separate lines of patterns (3.8t to 3.8v) are needed to describe the functional positions in the verb phrase:

3.8t vp> MP:

3.8u vp> MODHP: + (SN:) + MP:

3.8v vp> PROHP: + SN: + MP:

3.8w

MP: v...

[noDO:, nonfinite] arrive

[noDO:, finite, past] arrived

[noDO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] arrive

[noDO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] arrives

[yesDO:, nonfinite] select

[yesDO:, finite, past] selected

[yesDO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] select

[yesDO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] selects

[yes/noDO:, nonfinite] help

[yes/noDO:, finite, past] helped

[yes/noDO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] help

[yes/noDO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] helps

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, nonfinite] give

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, finite, past] gave

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] give

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] gives

3.8x

MODHP: modaux...

[possibility, past] might

[possibility, present] may

[certainty, past] would

[certainty, present] will

52

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

3.8y

PROHP: proaux...

[nonfinite] do

[finite, past] did

[finite, present, non3rdsng] do

[finite, present, 3rd sng] does

3.8z

SN: neg...

[negative] not

The pattern in line 3.8t indicates that a verb phrase may have just one position, MP:

(MAIN PREDICATER). Pattern 3.8u indicates that the MAIN PREDICATER may be preceded by a MODHP: (MODAL HELPING PREDICATER), and that an optional SN:

(SENTENCE NEGATER) position may occur between the two. Pattern 3.8v describes another possible arrangement: a PROHP: (PRO HELPING PREDICATER) position followed by an obligatory SENTENCE NEGATER and the obligatory MAIN

PREDICATER.

Choice line 3.8w indicates that a verb (v...) can occupy the MAIN PREDICATER position, choice line 3.8x indicates that a modal auxiliary (modaux...) can occupy the

MODAL HELPING PREDICATER position, choice line 3.8y indicates that a proauxiliary (proaux...) can occupy the PRO HELPING PREDICATER position, and choice line 3.8z indicates that a negative (neg...) can occupy the SENTENCE NEGATER position.

We have already analyzed a sentence with a modal auxiliary and a verb (cf. 3.9b’’’’ on p. 50). Here is a sentence that follows pattern 8v and thus has a proauxiliary and negater preceding a verb:

3.10

declcl>

S: P: DO:

np> vp> np>

D: H: PROHP: SN: MP: D: H: dart... n... proaux... neg... v... iart... n...

The delegates did not select a candidate.

The term proauxiliary is used analogously with the term pronoun. The prefix procame into English from Latin, where it meant "for." Thus, just as a pro noun can stand in for a noun, a pro auxiliary sometimes stands in for an auxiliary. In English negative sentences, the negative word not is placed after the first auxiliary (e.g., The delegates would not select a candidate ). When an affirmative sentence such as The delegates

53

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS selected a candidate , which has no auxiliary, needs to be converted into a negative sentence , then the proauxiliary must appear before the word not.

Some traditional grammars categorize not as an "adverb," but it clearly does not occupy the same positions in sentences as words like enthusiastically , which can occur initially or finally; nor does it have formal or meaningful similarities to such words.

Other, more linguistically based, grammars assign not the part-of-speech label “negative particle.” Here, it is simply labeled the “negative.”

Before finishing this discussion of the relationship between a grammar such as the one in 3.8 and the many constituent structure tree diagrams that such a grammar can generate, I would like to comment just a bit on some of the semantic feature terms listed with the verbs in 8w:

3.8w

MP: v...

[noDO:, nonfinite] arrive

[noDO:, finite, past] arrived

[noDO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] arrive

[noDO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] arrives

[yesDO:, nonfinite] select

[yesDO:, finite, past] selected

[yesDO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] select

[yesDO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] selects

[yes/noDO:, nonfinite] help

[yes/noDO:, finite, past] helped

[yes/noDO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] help

[yes/noDO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] helps

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, nonfinite] give

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, finite, past] gave

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, finite, present, non3rdsng] give

[yes/noDO:, yes/noIO:+DO:, finite, present, 3rd sng] gives

A complete listing of English verbs with defining semantic features would probably be even more complex than the complete listing for nouns, and the reasons why this is so will be discussed at some length in Chapter 10. Thus, the listings in 3.8w are especially oversimplified. For example, since only four verbs are included, no attempt is made even to begin to define them in specific terms. They are differentiated solely on the basis of features that specify whether they require or allow DIRECT OBJECTS (or in one case

INDIRECT OBJECTS) to follow them. The feature [noDO:] indicates that arrive prohibits a direct object (no speaker of English would say, e.g., *John arrived the delegate ). The feature [yesDO:] indicates that select requires a DIRECT

OBJECT(speakers of English are not likely to say or write, e.g., *John selected as if it were a complete sentence). The feature [yes/noDO:] indicates that help and give may occur with or without a direct object (e.g., John helped or John helped a delegate are equally acceptable). This feature [yes/noIO:+DO:] indicates that give allows an

INDIRECT OBJECT to precede a DIRECT OBJECT when one occurs (e.g., John gave the candidate a bribe ).

Here is another pair of terms from 3.8w that might be unfamiliar to you: [finite] refers to a verb form with a -prs or -pst tense inflectional suffix attached, and [nonfinite]

54

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS refers to a verb form without such a suffix. And finally, notice that present tense forms are distinguised by the terms [non3rdsng] and [3rdsng] according to whether or not the third-person-singular "s" allomorph of the present tense inflectional suffix is attached.

The purpose of this section has been to look very concretely at what a grammar is and to see how a grammar explains where the constituent structures of sentences come from. In order to do this, I constructed an extremely simplified partial grammar of the

English declarative clause. The grammar contained two kinds of principles: patterns and choices. Patterns specify the order of functional positions within clauses and phrases, and choices specify the types of formal clause, phrase, and part-of-speech categories that may occupy those positions. Most of the remaining chapters of this book will be dedicated to describing in some detail the various patterns and choices that constitute

English grammar. This chapter aimed to lay out the broad conceptual framework within which those details will be developed. It would nevertheless be useful, before moving on, to strengthen your understanding of that conceptual framework by analyzing some

English sentences that can be generated by the grammar in 3.8. Those sentences are in

Practice 9, along with a few suggestions about how to go about analyzing them.

PRACTICE 9 (WORKING WITH PATTERNS AND CHOICES)

The grammar in 3.8 on pp. 44 to 46 can be considered as a scientific model that seeks to explain the form and function of English words, phases, in at least a subset of English declarative clauses. The grammar's relationship to the clauses it explains is similar to the relationship between the hexagonal model of a carbon compound that a chemistry professor might hold in one hand and seek to relate to a piece of coal held in the other hand. Some linguists even assert that grammars like the one in 3.8 are models of psychological or even neurological realities; i.e., the various lines in 3.8 describe what speakers of English know about how to arrange words into phrases and phrases into clauses and also how to interpret the meanings of the words and the meaningful relationships that the words and phrases have to one another. That is, a grammar is a model of how speakers produce (generate) sentences. However, no one claims that a grammar such as the one in 3.8 provides a step-by-step guide for students who are charged by their professor to diagram a sentence according to the patterns and choices laid out in the grammar.

But that is exactly what I am now suggesting that you do: Try to figure out what constituent structure tree diagrams the grammar in 3.8 on pp. 44 to 46 would generate for each of the thirty sentence listed at the end of this paragraph. As you work on this, the most important activity you should engage in is constantly turning the pages back to pp. 44 to 46 in order to find out exactly which numbered pattern line or choice line is relevant to the clause, or phrase, or word that you are trying to diagram. The more you work at it, the easier it will become. Your aim is to understand as thoroughly as you can just what the difference between form and function is in grammar and exactly how the lines in 8 explain the one or the other. As limited as the grammar is (containing only a few dozen words and only a tiny fraction of the patterns and choices available to English speakers), it is nonetheless capable of generating thousands of grammatical

English sentences, not just the thirty listed in this exercise. Here are the sentences; why don’t you read all thirty of them and then read the sample analysis of sentence number 4, which which is given in the Feedback to Practice 9. Then try your hand at analyzing the remaining 29 sentences.

1. The delegates selected the enthusiastic candidate.

2. The delegates selected the candidate enthusiastically.

3. At the convention John gave enthusiastically.

55

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

4. Enthusiastically, the delegates at the convention selected the best candidate.

5. With enthusiasm, the delegates selected the candidate.

6. John helped the best candidate enthusiastically

7. Some conventions select better candidates.

8. John may help at the convention.

9. The delegates did not select a good candidate.

10. Some better candidates arrived there.

11. The convention selected the best candidate.

12. The delegates gave good bribes.

13. John would not select delegates.

14. Then the convention selected John.

15. The candidate at the convention did not help the delegates.

16. Some delegates arrived with John.

17. Candidates with enthusiasm arrived.

18. John helps convention delegates.

19. With enthusiasm, the convention delegates arrived.

20. Better delegates will select an enthusiastic candidate.

21. The best delegate at the convention helped John.

22. Good conventions give candidates enthusiasm.

23. Convention delegates arrived with enthusiasm

24. There conventions select candidates.

25. Conventions do not select the best candidates enthusiastically.

26. At the convention, some good delegates with enthusiasm will select an enthusiastic candidate.

27. A candidate gave John a bribe.

28. The candidates arrived then.

29. Some candidates might give the delegates bribes

30. John did not give the candidate a bribe at the convention

FEEDBACK TO PRACTICE 9 (WORKING WITH PATTERNS AND CHOICES)

I suggest beginning each analysis by trying to determine which variation of the declarative clause pattern (cf. 3.8a) applies to the sentence you are analyzing. I will use number 4 in this sample analysis: Enthusiastically, the delegates at the convention selected the best candidate.

Since 3.8a specifies that every declarative clause must have a SUBJECT and a

PREDICATER, first determine what they are. In the limited grammar governing the 30 exercise sentences, only four verbs are allowed; so the PREDICATER will end with one of them: arrive, help, select, or give. Remember, the verb could be accompanied in its verb phrase by a preceding modal auxiliary or proauxiliary and maybe by not. In sentence 4 the PREDICATER verb phrase consists of only one word, selected. Once you determine what the PREDICATER is, locate the

SUBJECT by asking who or what selected...? The answer to this question for sentence 4 is The

delegates at the convention selected . . . .

Next, decide whether or not there is a DIRECT OBJECT. To do this, take the SUBJECT and

PREDICATER sequence and turn it into a question: The delegates at the convention selected what?

or The delegates at the convention selected who(m)? If there is a noun phrase that fills in for the word what or the word who(m) , then it is a DIRECT OBJECT. In sentence 4 there is such a noun phrase: the best candidate. Another test that helps to identify a DIRECT OBJECT is this:

“If verb-ing is going on the DO: is the person or thing verbed.” In sentence 4 this test would work this way: “If selecting is going on the DO: is the think selected.” The answer is “the best candidate,” and so we have identified this noun phrase as a DIRECT OBJECT.

56

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

Next ask whether there is an INDIRECT OBJECT. INDIRECT OBJECTS appear between

PREDICATERS and DIRECT OBJECTS. If there is a noun phrase between the PREDICATER you have identified and a DIRECT OBJECT that you have identified, then it is an INDIRECT

OBJECT. In the grammar we are working with DIRECT OBJECTS can appear only with the verb give.

Give does not, however, require an INDIRECT OBJECT, or even a DIRECT

OBJECT, to accompany it in a sentence.

Next ask whether there is an adverb ( enthusiastically, there, then ) or a prepositional phrase at the very beginning or very end of the clause and which functions as an INITIAL CLAUSE

COMPLEMENT or FINAL CLAUSE COMPLEMENT. In sentence four, an adverb

( enthusiastically ) is indeed present, functioning as an INITIAL CLAUSE COMPLEMENT.

When you have assigned all of the words in the sentences to one of these functional positions in the clause, you can begin the diagram:

declcl>

ICC: S: P: DO:

advp> np> vp> np>

Enthusiastically, | the delegates at the convention | selected | the best candidate.

The next task is to examine carefully the patterns in the grammar for each of the phrase types that you have identified so far and to decide how to begin to diagram them. The advp> and vp> are quite simple for the sentence we are working on: enthusiastically is the HEAD adverb in the advp>, and selected is the MAIN PREDICATER verb in the vp>.

The two noun phrases are not so transparent, but they are no so difficult either. When more than one word occurs in a noun phrase, try to identify the HEAD noun first. Remember that there must always be a HEAD noun and it will be the one word which could do what the whole phrase does. In the sentence we are working on, the HEAD is delegates in the SUBJECT noun phrase and candidate in the DIRECT OBJECT noun phrase. Once the HEAD nouns are identified, the other elements are easy to identify (with the help of the relevant phrase patterns in the grammar on pp. 44 to 46).

Note especially that the prepositional phrase at the convention fills the POST MODIFIER position in the SUBJECT noun phrase the delegates at the convention . In diagramming the prepositional phrase, we have to remember that it will have a noun phrase within it, requiring us to consult the patterns and choices in the noun phrase one more time. Having done all of this, we can complete the diagam of sentence 4:

57

BASIC GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

declcl>

ICC: S: P: DO:

advp> np> vp> np>

H: D: H: PM: MP: D: M: H:

adv... dart... n... pp> v... dart... adj... n...

R: OP:

p... np>

D: H:

dart... n...

Enthusiastically, the delegates at the convention selected the best candidate.

58